How the Cruz Amendment Might Affect the Marketplace: Applying Different Rules to Competing Health Plans

As the Senate considers the Better Care Reconciliation Act (BCRA), a proposal to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act (ACA), amendments have been discussed to further change private health insurance market rules that apply under current law. Under the BCRA, current law health insurance market rules would still apply: Insurers in the non-group health insurance market are prohibited from turning applicants down or charging higher premiums based on health status and from excluding coverage for pre-existing conditions. In addition, all policies must provide major medical coverage for 10 categories of essential health benefits and must limit the annual out-of-pocket cost sharing (deductibles, co-pays and coinsurance) that people must pay for covered services in network (although states can alter those requirements through waivers).

However, one discussion draft amendment to the BCRA, suggested by Senator Ted Cruz (R-TX) as part of the July 13 version of the bill, would allow insurers in the non-group market to also sell some policies that would not be required to follow all of the ACA market rules. These noncompliant policies could turn people down or charge them more based on health status and could exclude coverage for pre-existing conditions. In addition, noncompliant policies would not have to meet ACA essential health benefit and cost sharing standards.

This brief examines the likely impact of such a change on the stability of coverage offered through non-group markets and on the number of individuals who might be affected.

Insurer Option to Sell Noncompliant Policies

The July 13 version of the BCRA provides that insurers in the non-group market would have the option to sell policies outside of the marketplace that would not be subject to most ACA market rules. These noncompliant policies could be medically underwritten (that is, they could turn applicants down, charge premiums based on health status, and deny coverage for pre-existing health conditions.) In addition, noncompliant policies would not have to cover essential health benefits, including preventive health services, and would not be limited in deductibles and other cost sharing they could require. Any insurer that sells compliant ACA policies in a marketplace rating area could elect to also sell noncompliant policies in that rating area outside of the marketplace. Insurers would be required to notify the Secretary of their election annually.

In practice, only those individuals healthy enough to pass medical underwriting would be able to choose between coverage under compliant vs. noncompliant plans. Prior to the ACA, people with certain medical conditions were routinely denied coverage under medically underwritten non-group policies. “Deniable” pre-existing conditions included cancer, HIV, diabetes, opioid addiction and other substance use disorders, severe mental health disorders, and pregnancy. People with less severe pre-existing conditions, including asthma, high blood pressure, depression, and allergies, could face other adverse underwriting actions, as well. Consequently, under a Consumer Freedom Option, people would be able to choose between compliant plans and less expensive noncompliant policies while they were in perfect health. By contrast, people with deniable pre-existing conditions would not be able to buy noncompliant policies at any price.

This uneven playing field of market rules would dramatically increase premiums compliant policies in the marketplace. Sicker people would be concentrated in marketplace plans. In effect, marketplace plans would become more like high-risk pools, and the price of these plans would skyrocket.

To offset premium increases, the July 13 version of the BCRA would take $70 billion in funding otherwise available to states, to finance a federal reinsurance program during the period 2020-2026. (The bill established a State Stability and Innovation Program with grants to states totaling $132 billion over this period. States could apply for program grants for several purposes – including funding coverage for high-risk individuals, funding cost sharing subsidies, making direct payments to providers, or funding state reinsurance programs to help stabilize the non-group insurance market.) The federal reinsurance program would make direct payments to insurers to help stabilize premiums for compliant marketplace plans. Federal reinsurance payments would be made to compliant plans offered by health insurers that also offer noncompliant plans. It is unclear whether funding would be sufficient to stabilize compliant plan premiums. However, leaders from the health insurance industry have urged that, even with new dedicated resources, the asymmetry of rules within the non-group market would be “simply unworkable in any form and would undermine protections for those with pre-existing medical conditions, increase premiums and lead to widespread terminations of coverage for people currently enrolled in the individual market.”

Finally, the BCRA clarifies that states retain authority to regulate the non-group health insurance market. States could limit the ability of insurers to elect to offer noncompliant plans by prohibiting the option entirely or by limiting the non-applicability of ACA market rules. Whether and how states might exercise this flexibility is difficult to predict.

Impact on Consumers Ineligible for Premium Subsidies

The Senate BCRA would continue ACA-like premium tax credits to subsidize the cost of coverage for low-and middle-income individuals. Like the ACA, premium tax credits under the BCRA would be tied to the cost of a benchmark marketplace plan, though the benchmark would have higher patient cost-sharing than under the ACA. Eligibility for premium tax credits would be capped at income of 350% of the federal poverty level (FPL), compared to 400% FPL under current law. Individuals eligible for tax credits would be required to pay a set percentage of their annual income toward a benchmark plan; the premium tax credit amount for each individual would be the difference between the actual cost of the benchmark plan and a person’s required contribution. Under this formula, as under current law, subsidy-eligible people would generally be shielded from annual premium cost increases, which would instead be absorbed by federal premium tax credits.

While people with pre-existing conditions eligible for premium tax credits would be cushioned from premium increases in compliant plans under the Cruz amendment, those ineligible for credits would not be protected.

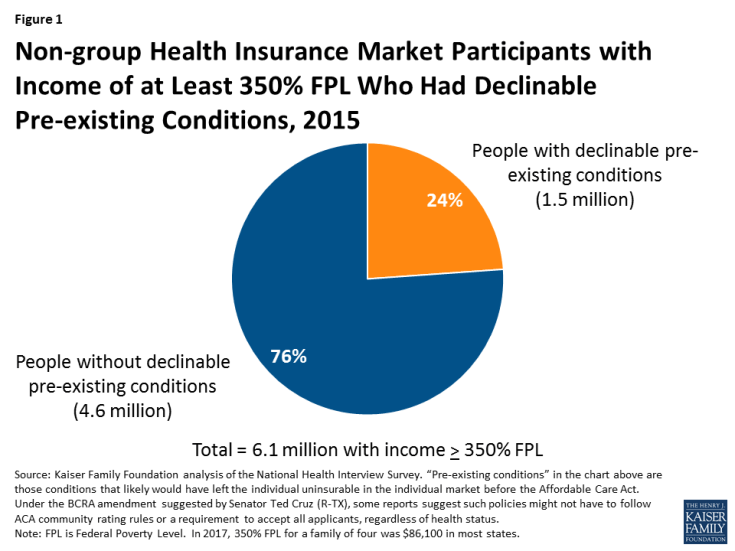

According to the National Health Interview Survey, approximately 40% of non-group market participants in 2015, or 6.1 million people, had income above 350% FPL. Most of these individuals purchased non-group coverage outside of the marketplace. Under the BCRA, these individuals would not be eligible for premium tax credits.

We estimate that, among the 6.1 million non-group market participants with incomes of at least 350% FPL, 24% (or about 1.5 million) would have pre-existing conditions that would have been considered automatically deniable by insurers prior to the ACA. (Figure 1)

Figure 1: Non-group Health Insurance Market Participants with Income of at Least 350% FPL Who Had Declinable Pre-existing Conditions, 2015

These 1.5 million individuals would likely be unable to buy non-compliant plans at any price. Among the three-quarters of other market participants with income over 350% FPL, millions would have other types of pre-existing conditions that were not considered automatically declinable prior to ACA, such as high-blood pressure, high cholesterol, asthma, and depression. Many in this group also could see a substantial increase in out-of-pocket spending for medical care that would offset any premium savings associated with less comprehensive policies.

Methods

To calculate nationwide prevalence rates of declinable health conditions, we reviewed the survey responses of nonelderly adults for all question items shown in Methods Table 1 using the CDC’s 2015 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). Approximately 27% of 18-64 year olds, or 52 million nonelderly adults, reported having at least one of these declinable conditions in response to the 2015 survey. For more details on methods and a list of declinable conditions included in this analysis, see our earlier brief: Pre-existing Conditions and Medical Underwriting in the Individual Insurance Market Prior to the ACA.

The programming code, written using the statistical computing package R, is available upon request for people interested in replicating this approach for their own analysis.