Explaining Health Care Reform: Risk Adjustment, Reinsurance, and Risk Corridors

As of January 1, 2014, insurers are no longer able to deny coverage or charge higher premiums based on preexisting conditions (under rules referred to as guaranteed issue and modified community rating, respectively). These aspects of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) – along with tax credits for low and middle income people buying insurance on their own in new health insurance marketplaces – make it easier for people with preexisting conditions to gain insurance coverage. However, if not accompanied by other regulatory measures, these provisions could have unintended consequences for the insurance market. Namely, insurers may try to compete by avoiding sicker enrollees rather than by providing the best value to consumers. In addition, in the early years of market reform insurers faced uncertainty as to how to price coverage as new people (including those previously considered “uninsurable”) gained coverage, potentially leading to premium volatility. This brief explains three provisions of the ACA – risk adjustment, reinsurance, and risk corridors – that were intended to promote insurer competition on the basis of quality and value and promote insurance market stability, particularly in the early years of reform.

Background: Adverse Selection & Risk Selection

One concern with the guaranteed availability of insurance is that consumers who are most in need of health care may be more likely to purchase insurance. This phenomenon, known as adverse selection, can lead to higher average premiums, thereby disrupting the insurance market and undermining the goals of reform. Uncertainty about the health status of enrollees could also make insurers cautious about offering plans in a reformed individual market or cause them to be overly conservative in setting premiums. To discourage behavior that could lead to adverse selection, the ACA makes it difficult for people to wait until they are sick to purchase insurance (i.e. by limiting open enrollment periods, requiring most people to have insurance coverage or pay a penalty, and providing subsidies to help with the cost of insurance).

Risk selection is a related concern, which occurs when insurers have an incentive to avoid enrolling people who are in worse health and likely to require costly medical care. Under the ACA, insurers are no longer permitted to deny coverage or charge higher premiums on the basis of health status. However, insurers may still try to attract healthier clients by making their products unattractive to people with expensive health conditions (e.g., in what benefits they cover or through their drug formularies). Or, certain products (e.g., ones with higher deductibles and lower premiums) may be inherently more attractive to healthier individuals. This type of risk selection has the potential to make the market less efficient because insurers may compete on the basis of attracting healthier people to enroll, as opposed to competing by providing the most value to consumers.

The ACA’s risk adjustment, reinsurance, and risk corridors programs were intended to protect against the negative effects of adverse selection and risk selection, and also work to stabilize premiums, particularly during the initial years of ACA implementation.

Each program varies by the types of plans that participate, the level of government responsible for oversight, the criteria for charges and payments, the sources of funds, and the duration of the program. The table below outlines the basic characteristics of each program.

| Table 1: Summary of Risk and Market Stabilization Programs in the Affordable Care Act | |||

| Risk Adjustment | Reinsurance | Risk Corridors | |

| What

the program does |

Redistributes funds from plans with lower-risk enrollees to plans with higher-risk enrollees | Provides payment to plans that enroll higher-cost individuals | Limits losses and gains beyond an allowable range |

| Why

it was enacted |

Protects against adverse selection and risk selection in the individual and small group markets, inside and outside the exchanges by spreading financial risk across the markets | Protects against premium increases in the individual market by offsetting the expenses of high-cost individuals | Stabilizes premiums and protects against inaccurate premium setting during initial years of the reform |

| Who

participates |

Non-grandfathered individual and small group market plans, both inside and outside of the exchanges | All health insurance issuers and self-insured plans contribute funds; individual market plans subject to new market rules (both inside and outside the exchange) are eligible for payment | Qualified Health Plans (QHPs), which are plans qualified to be offered on a health insurance marketplace (also called exchange) |

| How

it works |

Plans’ average actuarial risk will be determined based on enrollees’ individual risk scores. Plans with lower actuarial risk will make payments to higher risk plans.

Payments net to zero. |

If an enrollee’s costs exceed a certain threshold (called an attachment point), the plan is eligible for payment (up to the reinsurance cap).

Payments net to zero. |

HHS collects funds from plans with lower than expected claims and makes payments to plans with higher than expected claims. Plans with actual claims less than 97% of target amounts pay into the program and plans with claims greater than 103% of target amounts receive funds.

Payments net to zero. |

| When

it goes into effect |

2014, onward (Permanent) | 2014 – 2016 (Temporary – 3 years) | 2014 – 2016 (Temporary – 3 years) |

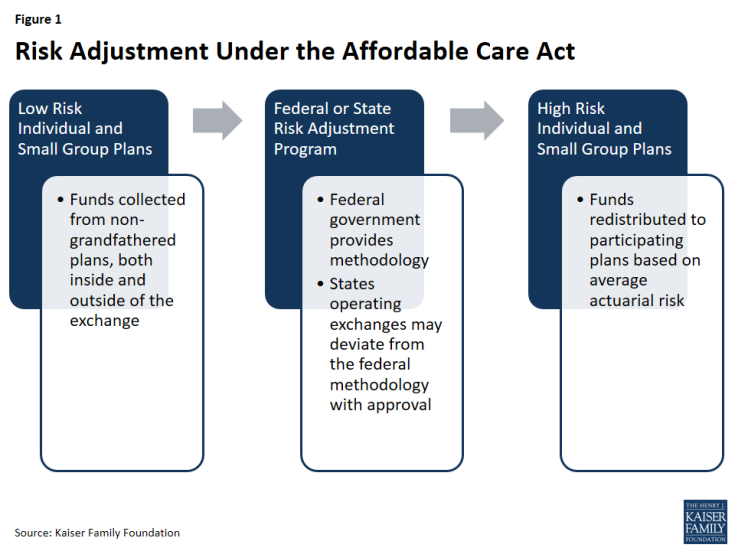

Risk Adjustment

The ACA’s risk adjustment program is intended to reinforce market rules that prohibit risk selection by insurers. Risk adjustment accomplishes this by transferring funds from plans with lower-risk enrollees to plans with higher-risk enrollees. The goal of the risk adjustment program is to encourage insurers to compete based on the value and efficiency of their plans rather than by attracting healthier enrollees. To the extent that risk selecting behavior by insurers – or decisions made by enrollees – drive up costs in the health insurance marketplaces (for example, if insurers selling outside the Exchange try to keep premiums low by steering sick applicants to Exchange coverage), risk adjustment also works to stabilize premiums and the cost of tax credit subsidies to the federal government.

Program Participation

The risk adjustment program applies to non-grandfathered plans in the individual and small group insurance markets, both inside and outside of the exchanges, with some exceptions. Plans in existence at the time the ACA was enacted in March 2010 were grandfathered under the law and are subject to fewer requirements. Plans lose their grandfathered status if they make significant changes (such as significantly increasing cost-sharing or imposing new annual benefit limits). Plans that were renewed prior to January 1, 2014, and are therefore not subject to most ACA requirements, are not part of the risk adjustment system. Multi-state plans and Consumer Operated and Oriented Plans (COOP) are subject to risk adjustment. Unless a state chooses to combine its individual and small group markets, separate risk adjustment systems operate in each market.

Government Oversight

States operating an exchange have the option to either establish their own state-run risk adjustment program or allow the federal government to run the program. States choosing not to operate an exchange or marketplace (and thus utilizing the federally-run exchange, called the Health Insurance Marketplace) do not have the option to run their own risk adjustment programs and must use the federal model. In states for which HHS operates risk adjustment, issuers are charged a fee to cover the costs of administering the program.

HHS developed a federally-certified risk adjustment methodology to be used by states or by HHS on behalf of states. States electing to use an alternative model must first seek federal approval and must submit yearly reports to HHS. States electing to run their own risk adjustment program must publish a notice of benefit and payment parameters by March 1 of the year prior to the benefit year; otherwise they will forgo the option to deviate from the federal methodology. Once a state’s alternative methodology is approved, it becomes federally-certified and can be used by other states. Massachusetts, the only state so far to operate its own risk adjustment program, will end is program in 2017. In 2017, HHS will operate risk adjustment programs in all states.

Calculation of Payments & Charges

Under risk adjustment, eligible insurers are compared based on the average financial risk of their enrollees. The HHS methodology estimates financial risk using enrollee demographics and claims for specified medical diagnoses. It then compares plans in each geographic area and market segment based on the average risk of their enrollees, in order to assess which plans will be charged and which will be issued payments.

Under HHS’s methodology, individual risk scores – based on each individual’s age, sex, and diagnoses – are assigned to each enrollee. Diagnoses are grouped into a Hierarchical Condition Category (HCC) and assigned a numeric value that represents the relative expenditures a plan is likely to incur for an enrollee with a given category of medical diagnosis. If an enrollee has multiple, unrelated diagnoses (such as prostate cancer and arthritis), both HCC values are used in calculating the individual risk score. Additionally, if an adult enrollee has certain combinations of illnesses (such as a severe illness and an opportunistic infection), an interaction factor is added to the person’s individual risk score. Finally, if the enrollee is receiving subsidies to reduce their cost-sharing, an induced utilization factor is applied to account for induced demand. Plans with enrollees that receive cost-sharing reductions under the ACA receive an adjustment because cost-sharing reductions may induce demand for health care and are not otherwise accounted for in the other premium stabilization programs. Once individual risk scores are calculated for all enrollees in the plan, these values are averaged across the plan to arrive at the plan’s average risk score. The average risk score, which is a weighted average of all enrollees’ individual risk scores, represents the plan’s predicted expenses. Under the HHS methodology, adjustments are made for a variety of factors, including actuarial value (i.e., the extent of patient cost-sharing in the plan), allowable rating variation, and geographic cost variation. Under risk adjustment, plans with a relatively low average risk score make payments into the system, while plans with relatively high average risk scores receive payments.

Transfers (both payments and charges) are calculated by comparing each plan’s average risk score to a baseline premium (the average premium in the state). Transfers are calculated for each geographic rating area, such that insurers offering coverage in multiple rating areas in a given state have multiple transfer amounts that are grouped into a single invoice. Transfers within a given state net to zero.

On March 25, 2016, CMS hosted a public conference and released a white paper to review risk adjustment methodology and build on the first several years of experience. The white paper examined proposals to account for partial year enrollees and prescription drug use in the risk adjustment model. CMS intends to propose that the risk adjustment model begin to account for partial year enrollees in the 2017 benefit year, and begin to account for prescription drug utilization in the 2018 benefit year. Beginning in 2017, HHS will also begin to incorporate preventive services into their simulation of plan liability, and will incorporate different trend factors for traditional drugs, specialty drugs, and medical and surgical expenditures. This is intended to better reflect the growth of prescription drug expenditures compared to other medical expenditures. The risk adjustment model will be recalibrated using the most recent claims data from the Truven Health Analytics 2012, 2013, and 2014 MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database (MarketScan). In response to issuer feedback from the 2014 benefit year of the risk adjustment program, CMS will also begin providing insurers with early estimates of health plan specific risk adjustment calculations. This is intended to give plans more timely information in order to set premiums. In addition, CMS has indicated that it is exploring other options to modify the permanent risk adjustment program to better adjust for higher-cost enrollees, as the temporary reinsurance program phases out in 2016.

Data Collection & Privacy

Under the federal risk adjustment program, to protect consumer privacy and confidentiality, insurers are responsible for providing HHS with de-identified data, including enrollees’ individual risk scores. States are not required to use this model of data collection, but are required to only collect information reasonably necessary to operate the risk adjustment program and are prohibited from collecting personally identifiable information. Insurers may require providers and suppliers to submit the appropriate data needed for risk adjustment calculations.

For each benefit year, an issuer of a risk adjustment covered plan or a reinsurance-eligible plan must establish a dedicated data environment (i.e. an EDGE server) and provide data access to HHS, in a timeframe specified by HHS, to be eligible for risk adjustment and/or reinsurance payments. CMS released guidance for EDGE Data submissions for the 2015 benefit year.

To ensure accurate reporting, HHS recommends that insurers first validate their data through an independent audit and then submit the data to HHS for a second audit. For the first two benefit years (2014 and 2015) no adjustments to payments or charges were made as HHS optimized the data validation process. In 2016 and onward, if an issuer fails to establish a dedicated distributed data environment, fails to submit risk adjustment data, or if any errors are found through these audits, the insurer’s average actuarial risk will be adjusted, along with any payments or charges. Because the audit process is expected to take more than one year to complete, the first adjustments to payments (for the 2016 benefit year) will be issued in 2018. Any issuer that fails to provide HHS access to EDGE server data in time to assess payments will be assessed a default risk adjustment charge. In 2015, 817 of 821 issuers participating in the risk adjustment program submitted the EDGE server data necessary to calculate risk adjustment transfers and 4 issuers were assessed the default charge.

Payments for the 2014 and 2015 Benefit Years

On Oct 1, 2015, HHS announced the results of the reinsurance, risk adjustment, and risk corridors programs for the first benefit year, 2014. For the 2014 benefit year of the risk adjustment program, $4.6 billion was transferred among insurers, and 758 total issuers participated in the program. An independent analysis found that the relative health of enrollees was the main determinant of whether an issuer received a risk adjustment payment. CMS reports that this is a sign that the risk adjustment formula is working as intended in transferring payments from plans with healthier enrollees to plans with sicker enrollees.

On June 30, 2016, HHS released a summary report on the results of the reinsurance and risk adjustment programs for the 2015 benefit year. For the 2015 benefit year of the risk adjustment program, risk adjustment transfers averaged 10% of premiums in the individual market and 6% of premiums in the small group market, similar to 2014. 821 issuers participated in the risk adjustment program. HHS also made available to each issuer of a risk adjustment covered plan a report that includes the issuer’s risk adjustment payment or charge.

Risk adjustment payments to issuers for benefit year 2015 will be sequestered at a rate of 7%, per government sequestration requirements for fiscal year 2016. HHS has suggested that risk adjustment payments sequestered in fiscal year 2016 will become available for payment to issuers in fiscal year 2017 without further Congressional action.

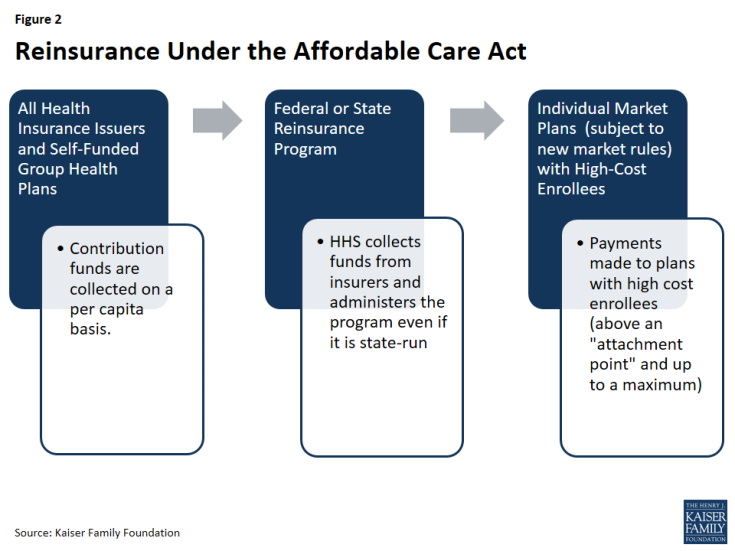

Reinsurance

The goal of the ACA’s temporary reinsurance program was to stabilize individual market premiums during the early years of new market reforms (e.g. guaranteed issue). The temporary program is in place from 2014 through 2016. The program transfers funds to individual market insurance plans with higher-cost enrollees in order to reduce the incentive for insurers to charge higher premiums due to new market reforms that guarantee the availability of coverage regardless of health status.

Reinsurance differs from risk adjustment in that reinsurance is meant to stabilize premiums by reducing the incentive for insurers to charge higher premiums due to concerns about higher-risk people enrolling early in the program, whereas risk adjustment is meant to stabilize premiums by mitigating the effects of risk selection across plans. Thus, reinsurance payments are only made to individual market plans that are subject to new market rules (e.g., guaranteed issue), whereas risk adjustment payments are made to both individual and small group plans. Additionally, reinsurance payments are based on actual costs, whereas risk adjustment payments are based on expected costs. As reinsurance is based on actual rather than predicted costs, reinsurance payments will also account for low-risk individuals who may have unexpectedly high costs (such as costs incurred due to an accident or sudden onset of an illness). Under reinsurance, some plans may receive payments for high-cost/high-risk enrollees, and still be eligible for payment for those enrollees under risk adjustment.

While risk adjustment payments net to zero within the individual and small group markets, reinsurance payments represent a net flow of dollars into the individual market, in effect subsidizing premiums in that market for a period of time. To cover the costs of reinsurance payments and administering the program, funds are collected from all health insurance issuers and third party administrators (including those in the individual and group markets). HHS issues reinsurance payments to plans based on need, rather than issuing payments proportional to the amount of contributions from each state.

Program Participation

All individual, small group, and large group market issuers of fully-insured major medical products, as well as self-funded plans, contribute funds to the reinsurance program. Reinsurance payments are made to individual market issuers that cover high-cost individuals (and are subject to the ACA’s market rules). State high risk pools are excluded from the program.

Government Oversight

States have the option to operate their own reinsurance program or allow HHS to run one for the state. For states that choose to operate their own reinsurance program, there is no formal HHS approval process. However, states’ ability to deviate from the HHS guidelines is limited: HHS collects all reinsurance contributions – even if the program is state-run – and all states must follow a national payment schedule. Additionally, states that wish to modify data requirements must publish a notice of benefit and payment parameters. States may collect additional funds if they believe the cost of reinsurance payments and program administration will exceed the amount specified at the national level. States wishing to continue reinsurance programs after 2016 may do so, but they may not continue to use funds collected as part of the ACA’s reinsurance program after the year 2018. Connecticut was the only state to operate its own reinsurance program for benefit years 2014 and 2015. In July 2016, Alaska signed into law a two-year reinsurance program that recreates Alaska’s high-risk pool as a reinsurance fund. Alaska’s reinsurance program will cover claims for 2015 and 2016 benefit years.

Calculation of Payments and Charges

The ACA set national levels for reinsurance funds at $10 billion in 2014, $6 billion in 2015, and $4 billion in 2016. Based on estimates of the number of enrollees, HHS set a uniform reinsurance contribution rate of $63 per person in 2014, $44 per person in 2015, and $27 per person in 2016.

Eligible insurance plans received reinsurance payments when the plan’s cost for an enrollee crossed a certain threshold, called an attachment point. HHS set the attachment point (a dollar amount of insurer costs, above which the insurer is eligible for reinsurance payments) at $45,000 in 2014 and 2015. Given the smaller reinsurance payments pool for 2016, HHS raised the attachment point to $90,000 for the 2016 benefit year. HHS also set a reinsurance cap (a dollar-amount threshold, above which the insurer is no longer eligible for reinsurance) at $250,000 in 2014, 2015, and 2016. HHS initially set the coinsurance rate (the percentage of the costs above an attachment point and below the reinsurance cap that were reimbursed through the reinsurance program) at 80 percent in 2014 and 50 percent in 2015 and 2016. If reinsurance contributions exceeded the amount of payments requested, then that year’s reinsurance payments to insurers were increased proportionately (i.e. the coinsurance rate increased up to 100%). For example, in 2014, HHS was ultimately able to pay out 100 percent of claims rather than 80 percent, and in 2015 HHS raised the coinsurance rate to 55.1 percent. If surplus reinsurance funds remained available, they were rolled forward to the next benefit year. For example, $1.7 billion in surplus reinsurance funds collected for the 2014 benefit year were rolled forward to the 2015 benefit year. Similarly, if reinsurance contributions had fallen short of the amount requested for payments, then that year’s reinsurance payments would have decreased proportionately. Overall, total payments could not exceed the amount collected through contributions by insurers and third-party administrators.

States opting to raise additional reinsurance funds may do so by decreasing the attachment point, increasing the reinsurance cap, and/or increasing the coinsurance rate. States may not make changes to the national attachment point, reinsurance cap, or coinsurance rate that would result in lower reinsurance payments.

Data Collection & Privacy

Payment amounts made to eligible individual market insurers were based on medical cost data (to identify high-cost enrollees, for which plans receive reinsurance payment). Therefore, in order to calculate reinsurance payments, HHS or state reinsurance entities must either collect or be allowed access to claims data as well as data on cost-sharing reductions (because reinsurance payments were not made for costs that have already been reimbursed through cost sharing subsidies). In states for which HHS ran the reinsurance program, HHS used the same distributed data collection approach used for the risk adjustment program (i.e. an EDGE server) and similarly ensured that the collection of personally identifiable information was limited to that necessary to calculate payments. HHS proposed to conduct audits of participating insurers as well as states conducting their own reinsurance programs.

For the first two benefit years (2014 and 2015) no adjustments to reinsurance payments were made as HHS optimized the data validation process. In 2016, if an issuer fails to establish a dedicated distributed data environment or fails to adhere to reinsurance data submission requirements, the insurer may forfeit reinsurance payments. In 2015, 574 of 575 issuers participating in the reinsurance program submitted the EDGE server data necessary to calculate reinsurance payments.

Payments for the 2014 and 2015 Benefit Years

In June 2015, CMS announced the results of the reinsurance program for the first benefit year, 2014. In 2014, reinsurance contributions ($9.7 billion) exceeded requests for payments ($7.9 billion) and CMS was able to payout 100 percent of eligible claims rather than 80 percent – this amounted to $7.9 billion in reinsurance payments made to 437 issuers nationwide. Following these payments, approximately $1.7 billion in surplus reinsurance funds from the 2014 benefit year remained available, and were rolled forward to the 2015 benefit year.

CMS used this surplus of $1.7 billion, combined with additional collections of reinsurance contributions for the 2015 benefit year, to make an early partial reinsurance payment to issuers for the 2015 benefit year in March and April 2016. CMS calculated this early payment based on accepted enrollment and claims data as of February 1, 2016, at a coinsurance rate of 25%. CMS stated that reinsurance funds not paid out through this early payment will be paid out in late 2016, as part of the standard reinsurance payment process.

On June 30, 2016, CMS announced the results of the reinsurance program for the second benefit year, 2015. In 2015, estimated reinsurance contributions ($6.5 billion) were smaller than requests for payments ($14.3 billion). CMS estimates it will make $7.8 billion in reinsurance payments to 497 of the 575 participating issuers nationwide at a coinsurance rate of 55.1%.

CMS has collected approximately $5.5 billion in reinsurance contributions for 2015, with approximately $1 billion more scheduled to be collected on or before November 15, 2016. Any reinsurance contribution amounts collected above $6 billion for the 2015 benefit year are required to be allocated to the U.S. Treasury on a pro rata basis as an operating expense of the program. Combined with the surplus of $1.7 billion from 2014, CMS estimates it will have approximately $7.8 billion in reinsurance contributions available to be distributed as payments to issuers for the 2015 benefit year. On June 30, 2016 HHS made available to each issuer of a reinsurance-eligible plan a report that includes the issuer’s initial, estimated reinsurance payment for the 2015 benefit year. On August 11, 2016, CMS released an analysis based on reinsurance payments that suggests per-enrollee costs in the individual market were essentially unchanged between 2014 and 2015.

Reinsurance payments to issuers for benefit year 2015 will be sequestered at a rate of 6.8% per government sequestration requirements for fiscal year 2016. HHS has suggested that risk adjustment payments sequestered in fiscal year 2016 will become available for payment to issuers in fiscal year 2017 without further Congressional action.

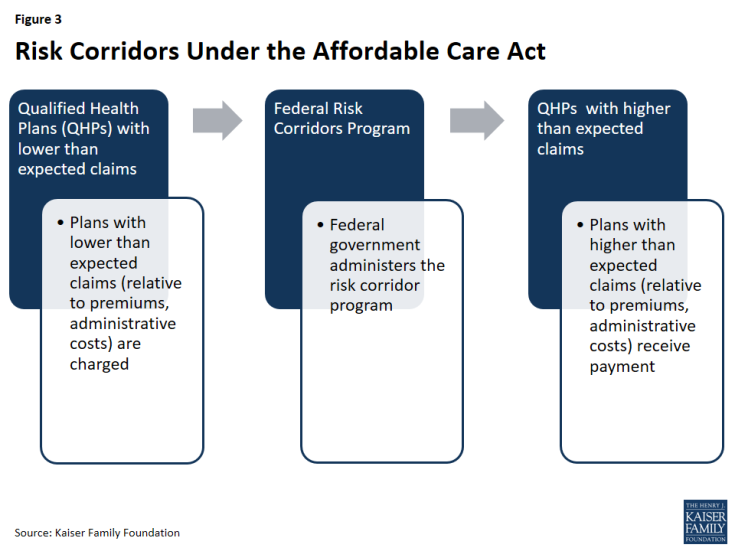

Risk Corridors

The ACA’s temporary risk corridor program was intended to promote accurate premiums in the early years of the exchanges (2014 through 2016) by discouraging insurers from setting premiums high in response to uncertainty about who will enroll and what they will cost. The program worked by cushioning insurers participating in exchanges and marketplaces from extreme gains and losses.

The Risk Corridors program set a target for exchange participating insurers to spend 80% of premium dollars on health care and quality improvement. Insurers with costs less than 3% of the target amount must pay into the risk corridors program; the funds collected were used to reimburse plans with costs that exceed 3% of the target amount.

This program was intended to work in conjunction with the ACA’s medical loss ratio (MLR) provision, which requires most individual and small group insurers to spend at least 80% of premium dollars on enrollee’s medical care and quality improvement expenses, or else issue a refund to enrollees.

Program Participation

All Qualified Health Plans (or QHPs, plans qualified to participate in the exchanges) were subject to the risk corridor program. Only those plans with expenses falling outside of allowable ranges made payments to the program (or qualified to receive payments). Qualified Health Plan (QHP) issuers may also offer QHPs outside of the exchange, in which case the QHP outside of the exchange were also subject to the risk corridors program.

Government Oversight

The risk corridor program was federally administered. HHS charged plans with larger than expected gains and made payments to plans with larger than expected losses.

Calculation of Payments and Charges

Each year, each Qualified Health Plan was assigned a target amount for what are called allowable costs (expenditures on medical care for enrollees and quality improvement activities) based on its premiums. Allowable costs included medical claims and costs associated with quality improvement efforts, as defined in the ACA’s medical loss ratio (MLR) calculations. Insurers must also account for any cost-sharing reductions received from HHS by reducing their allowable costs by this amount. If an insurer’s actual claims fell within plus or minus three percent of the target amount (i.e. premiums less allowable costs), it made no payments into the risk corridor program and received no payments from it. In other words, the plan was fully at risk for any loss or gain. QHPs with lower than expected claims paid into the risk corridor program:

- A QHP with claims falling below its target amount by 3% – 8% paid HHS in the amount of 50% of the difference between its actual claims and 97% of its target amount.

- A QHP with claims falling below its target amount by more than 8% paid 2.5 percent of the target amount plus 80% of the difference between their actual claims and 92% of its target.

HHS provides an example of an insurer with a $10 million target amount and actual claims of $8.8 million (or 88% of the target amount). The insurer would have to pay $570,000 to the risk corridors program because (2.5%*$10 million) + (80%*((92%*10 million)-8.8 million) = 570,000.

Conversely, HHS reimbursed plans with higher than expected costs:

- A QHP with actual claims that exceeded its target amount by 3% to 8% received a payment in the amount of 50% of the amount in excess of 103% of the target.

- A QHP with claims that exceed its target amount by more than 8% received payment in the amount of 2.5% of the target amount plus 80% of the amount in excess of 108% of the target.

In response to reports of individual market plan cancelations in November 2013, HHS instituted a transitional policy allowing certain plans to be reinstated if state regulators agree to adopt a similar transitional policy. As this policy change affected the composition of the exchange risk pool, HHS modified the risk corridors program in 2015 to change the way allowable costs are calculated (i.e., by increasing the ceiling on administrative costs and the profit margin floor by 2 percent).

In the original statute, risk corridor payments were not required to net to zero, meaning that the federal government could experience an increase in revenues or an increase in costs under the program. However, in the 2015 and 2016 appropriations bills, Congress specified that payments under the risk corridor program made to insurers in 2015 could not exceed collections from that year, and that CMS cannot transfer funds from other accounts to pay for the risk corridors program. This made the risk corridors program revenue neutral –meaning that only contributions collected from insurers could be used to fund payments for the risk corridor program. In the event that claims exceeded funds collected in a given year, CMS paid out claims pro rata and carried over deficiencies to be paid in the following year before any other claims are paid in that year. If the three-year risk corridors program ends with outstanding claims, HHS has stated it will work with Congress to secure funding for outstanding risk corridors payments, subject to the availability of appropriations.

Data Collection & Privacy

In order to calculate payments and charges for the risk corridors program, QHPs were required to submit financial data to HHS, including the actual amount of premiums earned as well as any cost-sharing reductions received. To reduce the administrative burden on insurers, HHS tied the data collection and validation requirements for the risk corridors to that of the Medical Loss Ratio (MLR) provision of the ACA. HHS will also conduct audits for the risk corridors program in conjunction with audits for the reinsurance and risk corridors program to minimize the burden on insurers.

Payments for the 2014 Benefit Year

On October 1, 2015, CMS announced that total risk corridors claims for 2014 amounted to $2.87 billion, and that insurer risk corridor contributions totaled $362 million. As a result, risk corridor payments for 2014 claims were paid out at 12.6% of claims. CMS anticipates that the remaining claims for 2014 will be paid out from 2015 risk corridor collections, and any shortfalls from 2015 claims will be covered by 2016 collections in 2017. If there are still outstanding claims when the risk corridors program ends in 2017, HHS has stated it will work with Congress to explore other sources of funding for risk corridor payments, subject to availability of appropriations.

Conclusion

The Affordable Care Act’s risk adjustment, reinsurance, and risk corridors programs were designed to work together to mitigate the potential effects of adverse selection and risk selection. All three programs aimed to provide stability in the early years of a reformed health insurance market, with risk adjustment continuing over the long-term. Many health insurance plans are subject to more than one premium stabilization program, and while the programs have similar goals, they are designed to be complementary. Specifically, risk adjustment is designed to mitigate any incentives for plans to attract healthier individuals and compensate those that enroll a disproportionately sick population. Risk corridors were intended to reduce overall financial uncertainty for insurers, though they largely did not fulfill that goal following congressional changes to the program. Reinsurance compensated plans for their high-cost enrollees, and by the nature of its financing provided a subsidy for individual market premiums generally over a three-year period. Premium increases are expected to be higher in 2017 in part due to the end of the reinsurance program.