KFF Health Misinformation Tracking Poll Pilot

On Sept. 15, KFF released three follow-up reports examining the exposure to, and belief in, health misinformation among key groups, as well as their trust in different sources of health misinformation:

- Addressing Misinformation Among Black Adults

- Addressing Misinformation Among Hispanic Adults

- Addressing Misinformation in Rural Communities

Introduction

While health misinformation and disinformation long preceded the pandemic, the pervasiveness of false and inaccurate information about COVID-19 and vaccines brought into further focus the extent to which misinformation can distort public health policy debates and impact the health choices individuals make. KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor surveys in 2021 and 2022 found that large shares of the public believed or were uncertain about false claims related to COVID vaccines and treatments, including myths about the vaccines’ effects on pregnancy and fertility. These surveys also highlighted the roles of traditional and social media as vehicles for spreading and/or combatting misinformation, showing a strong relationship between individuals’ trusted news sources and their propensity to believe false claims about COVID-19.

KFF has focused on providing reliable, accurate, and non-partisan information to help inform health policy in the United States. Yet, in a time where health-related misinformation is so easily accessible and disseminated, understanding the dynamics of misinformation is important to help ensure a robust and fact-based health policy environment. With this understanding, KFF is designing a new program that will identify and track the rise and prevalence of health-related misinformation in the United States, with a special focus on communities that are most adversely affected by health misinformation.

KFF is releasing our Health Misinformation Tracking Poll Pilot as part of this effort, examining the public’s media use and trust in sources of health information and measuring the reach of specific false and inaccurate claims surrounding three health-related topics: COVID-19 and vaccines, reproductive health, and gun violence. Accompanying this overview report of the pilot poll, KFF also released snapshot reports to the field, examining the implications for understanding and combatting misinformation among Black adults, Hispanic adults, and rural residents. Future surveys will explore other health topics for which misinformation has been found to be circulating.

The Misinformation Tracking Poll will work in tandem with our forthcoming Health Misinformation Monitor, a detailed report of the landscape of current health misinformation messages circulating among the public, sent directly to professionals working to combat misinformation. The Misinformation Monitor will be an integral part of KFF’s efforts to deeper analyze the dynamics of misinformation and inform a robust, fact-based health information environment, and will inform the topics we will ask about on future Health Misinformation Tracking Polls.

Key Takeaways for the Field

Health misinformation is widespread, yet the KFF Health Misinformation Tracking Poll Pilot presents a more nuanced perspective on what information people believe. Beliefs influenced by misinformation are not universally entrenched, and a significant portion of the public falls in the middle, susceptible to false claims, but not already bought in. These individuals hold tentative beliefs that lean towards or against misinformation, providing an opportunity to foster a more fact-based public understanding of health issues and informed dialogue.

While it is true that most adults have heard or read many of the false and inaccurate health claims asked about in the survey, relatively small shares of the public have both heard and believe misinformation about central health topics such as COVID-19 and vaccines, reproductive health, and firearm violence and safety. Moreover, while there are some adults who, when presented with false and inaccurate health misinformation, say they believe them to be definitely true, this is a relatively small share of the public. Most adults are uncertain about various items of health misinformation and fall in a potentially “malleable middle” who say the claims are “probably” true or “probably” false. While exposure to misinformation may not necessarily convert the public into ardently believing false health claims, it is likely adding to confusion and uncertainty about already complicated public health topics and may lead to decision paralysis when it comes to individual health care behaviors and choices. In any case, this “malleable middle” presents an opportunity for tailored interventions.

Furthermore, reinforcing accurate information may need to go hand-in-hand with combatting false health claims. When adults in the survey were asked to provide an example of COVID-19 misinformation they have read or heard, some individuals presented true claims as examples of misinformation. While the focus of some anti-misinformation efforts is on combating false claims that circulate widely, the survey reveals that there is a parallel challenge of true claims not being believed. This finding suggests allocating sufficient attention to addressing the skepticism and disbelief surrounding accurate information.

Some groups seem to be more susceptible to misinformation than others, with larger shares of Black and Hispanic adults, those with lower levels of educational attainment, and those who identify politically as Republicans or lean that way saying many of the misinformation items examined in the poll are “probably true” or “definitely true.” News sources also matter as those who say they regularly consume news from One America News Network (OANN), Newsmax, and to a smaller extent Fox News, are consistently more likely to believe most of the misinformation items asked about in the survey.

Media and other messengers can undoubtedly play a key role in efforts to address and to counter health misinformation. Local TV news and network news are among the most used news sources and also among the most likely to be trusted when it comes to health information. While many adults report frequently using social media, few say they would trust health information they may see on these platforms. Despite this, adults who frequently use social media to find health information and advice are more likely to believe that certain false statements about COVID-19 and reproductive health are definitely or probably true.

In an age of declining trust in institutions, some sources are more trusted than others and may have an important role to play in addressing misinformation. As the most trusted source of health information for the public, individual doctors may have an essential role to play in helping dispel false health claims. Additionally, while few media sources are widely trusted by the public as a source of health information, local news stations and network TV news stand out for their widespread use as a source of news and their relatively high level of trust among the public.

The following are the specific health-related claims that have been shown to be false, which were asked about in this KFF Health Misinformation Tracking Poll pilot survey. See the Appendix for more information the sources used to document each claim:

False claims about COVID-19 and vaccines:

“The COVID-19 vaccines have caused thousands of deaths in otherwise healthy people.”

“Ivermectin is an effective treatment for COVID-19.”

“The COVID-19 vaccines have been proven to cause infertility.”

“More people have died from the COVID-19 vaccines than have died from the COVID-19 virus.”

“The measles, mumps, rubella vaccines, also known as MMR, have been proven to cause autism in children.”

False claims about reproductive health:

“Using birth control like the pill or IUDs makes it harder for most women to get pregnant after they stop using them.”

“Sex education that includes information about contraception and birth control increases the likelihood that teens will be sexually active.”

False claims about gun violence:

“People who have firearms at home are less likely to be killed by a gun than people who do not have a firearm.”

“Most gun homicides in the United States are gang related.”

“Armed school police guards have been proven to prevent school shootings.”

False claim about the Affordable Care Act:

In addition to the false claims above, the survey also asked about the longstanding false claim that the Affordable Care Act established government “death panels” for people of Medicare in the question below:

“To the best of your knowledge, did the Affordable Care Act establish a government panel to make decisions about end-of-life care for people on Medicare?”

Exposure to and Belief in Health Misinformation Claims

Overall, health misinformation is widely prevalent in the U.S. with 96% of adults saying they have heard at least one of the ten items of health-related misinformation asked about in the survey. The most widespread misinformation items included in the survey were related to COVID-19 and vaccines, including that the COVID-19 vaccines have caused thousands of deaths in otherwise healthy people (65% say they have heard or read this) and that the MMR vaccines have been proven to cause autism in children (65%).

Regardless of whether they have heard or read specific items of misinformation, the survey also asked people whether they think each claim is definitely true, probably true, probably false, or definitely false. For most of the misinformation items included in the survey, between one-fifth and one-third of the public say they are “definitely” or “probably true.” While the most frequently heard claims are related to COVID-19 and vaccines, the most frequently believed claims were related to guns, including that armed school police guards have been proven to prevent school shootings (60% say this is probably or definitely true), that most gun homicides in the U.S. are gang-related (43%), and that people who have firearms at home are less likely to be killed by a gun than those who do not (42%).

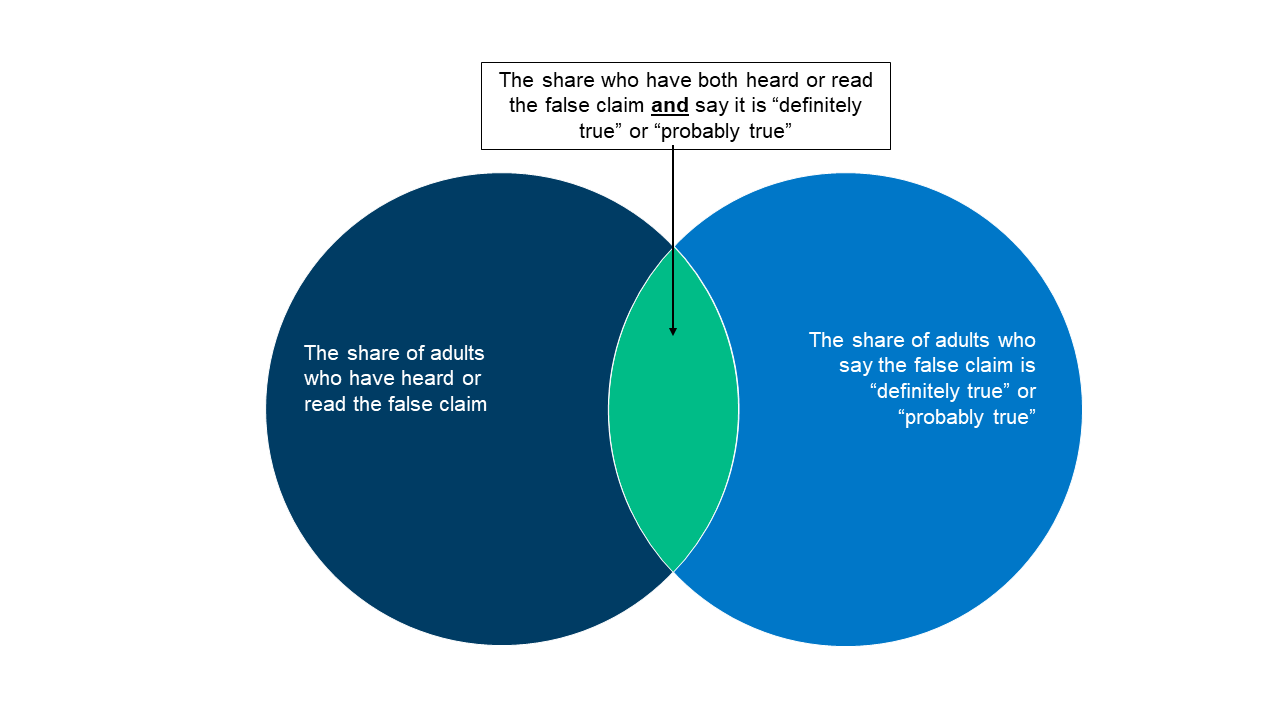

Combining these measures, the share of the public who both have heard each false claim and believe it is probably or definitely true ranges from 14% (for the claim that “more people have died from the COVID-19 vaccine than from the virus”) to 35% (“armed school police guards have been proven to prevent school shootings”).

Measures of Health Misinformation

This report examines three measures of health misinformation among the public. Adults were asked whether they had heard or read specific false health-related statements. Regardless of whether they have heard or read specific items of misinformation, all were asked whether they thought each claim was definitely true, probably true, probably false, or definitely false. We then combined these two measures in order to examine the share who have heard the false claims and believe it is definitely or probably true.

Uncertainty is high when it comes to health misinformation. While fewer than one in five adults say each of the misinformation claims examined in the survey are “definitely true,” larger shares are open to believing them, saying they are “probably true.” Many lean towards the correct answer but also express uncertainty, saying each claim is “probably false.” Fewer tend to be certain that each claim is false, with the exception of the claim that more people have died from the COVID-19 vaccines than from the virus itself, which nearly half the public (47%) recognizes as definitely false.

The range of people’s responses when presented with false claims – ranging from definitely true to definitely false – suggests different potential approaches for directing interventions among different groups. Those who say false health claims are “probably false” may benefit from having accurate information reinforced to them by trusted messengers such as their doctor or family and friends in the medical or health fields. However, those who say health-related misinformation items are “probably true” may require a different approach. While adults in each level of belief and disbelief of health misinformation present a unique opportunity for different tactics of interventions and outreach, the remainder of this report focuses on the group who say the false claims examined were “definitely true” or “probably true,” as this group represents adults who have bought in or are at the greatest risk of buying into the health misinformation items asked about in this survey.1

COVID-19 and Vaccine Misinformation

Across the five COVID-19 and vaccine related misinformation items, adults without a college degree are more likely than college graduates to say these claims are definitely or probably true. Notably, Black adults are at least ten percentage points more likely than White adults to believe some items of vaccine misinformation, including that the COVID-19 vaccines have caused thousands of sudden deaths in otherwise healthy people, and that the MMR vaccines have been proven to cause autism in children. Black (29%) and Hispanic (24%) adults are both more likely than White adults (17%) to say that the false claim that “more people have died from the COVID-19 vaccine than have died from the COVID-19 virus” is definitely or probably true. Those who identify as Republicans or lean towards the Republican Party and pure independents stand out as being more likely than Democratic leaning adults to say each of these items is probably or definitely true. Across community types, rural residents are more likely than their urban and suburban counterparts to say that some false claims related to COVID vaccines are probably or definitely true, including that the vaccines have been proven to cause infertility and that more people have died from the vaccine than from the virus.

Educational attainment appears to play a particularly important role when it comes to susceptibility to COVID-19 and vaccine misinformation. Six in ten adults with college degrees say none of the five false COVID-19 and vaccine claims are probably or definitely true, compared to less than four in ten adults without a degree. Concerningly, about one in five rural residents (19%), adults with a high school education or less (18%), Black adults (18%), Republicans (20%), and independents (18%) say four or five of the false COVID-19 and vaccine misinformation items included in the survey are probably or definitely true.

Reproductive Health Misinformation

The KFF Health Misinformation Tracking Poll asked about two misinformation items related to reproductive health and these two false claims appear to have different audiences. When asked about birth control leading to issues getting pregnant after cessation, younger adults – particularly younger women – are more likely to have heard this and to say this is probably or definitely true. However, when asked about sex education among teens leading to more sexual activity, older adults are more likely to say it is definitely or probably true. For both of these false reproductive health claims, adults without a college education, Republicans, and pure independents are more likely than their counterparts to say the claims are probably or definitely true. Black and Hispanic adults – groups who experience disparities in both health outcomes and in access to care – are more likely than White adults to say both of these false reproductive health claims are definitely or probably true.

Gun-Related Misinformation

When it comes to misinformation on gun-related violence, educational attainment again appears related to susceptibility to misinformation as those without a college degree are more likely than college graduates to say the firearm misinformation items are probably or definitely true. Notably, White (63%) and Hispanic (57%) adults are more likely than Black adults (48%) to say the claim that armed school police have been proven to prevent school shootings is definitely or probably true. Gun-related misinformation appears to be heavily politically charged, with Republicans and independents more likely than Democrats to say each of the claims regarding gun-related violence are probably or definitely true. Nearly three in four rural residents (73%) say that the claim that armed school police have been proven to prevent school shootings is definitely or probably true compared to fewer urban (56%) and suburban (58%) residents.

Gun owners are no more likely to have heard each of these items compared to those who do not own a gun, yet they are more likely to say each is definitely or probably true.

Affordable Care Act Misinformation

Some misinformation claims can have longevity and lead to longstanding public confusion and uncertainty. The KFF Health Misinformation Tracking Poll also asked about the false claim that the Affordable Care Act (ACA) established a government panel to make decisions on end-of-life care for people on Medicare. This is a long-standing myth about the ACA and previous KFF research has found that most adults could not accurately identify that the law did not set up such a panel. In the latest survey, seven in ten adults say they are not sure whether the ACA established a government panel to make end-of-life decisions for people on Medicare, and a further 8% incorrectly answer that the law did establish these panels. Just one in four adults (23%) – including three in ten Democrats – know that the ACA did not establish these so-called “death panels.” Notably, adults ages 65 and older (most of whom have Medicare coverage) are more likely than adults under the age of 30 to correctly answer that the ACA did not establish government panels for end-of-life decisions for those on Medicare.

Views of Health Misinformation and Responsibility for Combatting It

Large majorities of U.S. adults say that the spread of false and inaccurate information generally (86%) and the spread of false and inaccurate information related to health issues (74%) are major problems. This includes large shares across age, gender, education, and partisanship.

While a large majority of the public believes that false and inaccurate health information is a major problem, the COVID-19 pandemic underscored the complex nature of what the public sees as health misinformation in the United States. The current polarized political and media climate can lead to very different views of what constitutes misinformation.

The KFF Health Misinformation Tracking Poll asked adults to provide an example of COVID-19 misinformation that they have read or heard, and many examples were in direct contradiction with one another. For example, many cited things they had heard about facemasks that they perceive to be untrue. However, while some cited claims of masks not helping to curb the spread of the virus as misinformation, others cited claims that masking did help prevent the spread as a misinformation item. Similarly, adults provide contradictory claims about the COVID-19 vaccines’ safety and efficacy as examples of misinformation they have read or heard.

In Their Own Words: Can you provide an example of misinformation related to COVID-19 that you read or heard about in the media or elsewhere?

“That wearing a mask would not help prevent the spread” – 35 year-old Hispanic woman in Mississippi

“That masks stop the spread” – 52 year-old White woman in Ohio

“That masks don’t need to be worn” – 72 year-old White woman in Arizona

“The use of masks reduces chances of getting COVID-19” – 26 year-old Hispanic man in Texas

“Taking the COVID shot will protect you that was all a LIE.” – 54 year-old Hispanic man in Florida

“The vaccines were ok to use” – 27 year-old Black woman in Texas

“Vaccines not being effective” – 62 year-old White woman in Massachusetts

“Vaccines do not work or are dangerous” – 75 year-old White woman in New Jersey

This lack of consensus on what constitutes health misinformation adds to the difficulty of curbing the spread of false and inaccurate health and medical claims. Nonetheless, the public sees a role for government, media, and social media companies to tackle this issue. At least two-thirds of adults say that Congress, President Biden, the U.S. news media, and social media companies are not doing enough to limit the spread of false and inaccurate health information. Despite often divided views on the role of government and media, majorities of adults across age, gender, education, and partisanship say each of these entities is not doing enough.

Trusted Sources of Information and News

With large shares of the public unable to identify many health-related misinformation items as definitely false, trusted messengers and sources have an important role to play in efforts to combat the proliferation of health misinformation. Not surprisingly, individual doctors are the most trusted source, with 93% of the public saying they have a great deal or a fair amount of trust in their own doctor to make the right recommendations on health issues.

When it comes to government agencies, most adults have at least a fair amount of trust in the FDA and CDC to make the right recommendations on health issues, though just one in four have a great deal of trust in the CDC and one in five have a great deal of trust in the FDA. Fewer say they trust the Biden Administration on health issues, and Republicans are less likely than Democrats to trust the Administration, as well as the CDC and the FDA.

Traditional News Media Use and Trust

The proliferation of media sources has led to many adults having a varied media diet. Local TV news, national network news, and digital and online news aggregators are the top news sources for U.S. adults, with over half saying they regularly read, watch, or listen to each.

There are variations in consumption of traditional news sources. Adults under age 30 are less likely than older adults to say they regularly watch local news but are more likely to use digital or online news aggregators that summarize various traditional and nontraditional news sources, such as Apple or Yahoo News. More than seven in ten Black (77%) and Hispanic (71%) adults say they regularly watch their local TV news station compared to 59% of White adults. Similarly, White adults (52%) are less likely to watch national network news regularly compared to Black (74%) and Hispanic (65%) adults. A majority of Republicans (57%) say they regularly watch Fox News to say up-to-date on current events, whereas a majority of Democrats (55%) say they watch CNN. Yet notably, more than six in ten Democrats and Republicans say they also regularly watch their local TV news channel, underscoring the wide reach of local news.

Regardless of whether they are regular viewers, the survey measured how much individuals would trust information about health issues that was reported by each of these sources. At least seven in ten U.S. adults say they would have at least “a little” trust in health information reported by their local TV news station, national network news, or their local newspaper. However, fewer than three in ten adults say they would have a lot of trust in health information reported by each of the media sources asked about in the survey.

The picture of trust in health information from various news sources looks somewhat different when looking only at those who are regular users of each source. Not surprisingly, regular users are much more likely than those who do not use each news source to say they would have a lot of trust in health information reported by that source. However, there is variation among news sources in how much their regular users trust the information they report. For example, majorities of regular users of NPR (59%) and the New York Times (52%) say they would trust health information reported on these platforms “a lot,” while a third of regular MSNBC viewers (34%) and Fox News viewers (36%) say they would place a lot of trust in health information reported there. For most other sources, the share of regular users who say they would have a lot of trust in health information they report ranges from three to four in ten.

Social Media Use and Trust

Most adults (55%) say they use social media at least once a week to keep up-to-date on news and current events, including a third (33%) who say they use it every day. About one in four (24%) say they use social media at least weekly to find health information and advice, though four in ten say they “never” do this. Larger shares of Hispanic and Black adults compared to White adults, and younger adults compared to older adults, say they regularly use social media for both news and health information. Hispanic adults are particularly likely to say they regularly use social media, with seven in ten (70%) saying they use it weekly for news and current events and half (49%) saying they use it weekly for health information and advice. While similar shares across education and income groups say they use social media for news, larger shares of those without college degrees and those living in lower-income households report using social media to find health information and advice compared to those with college degrees and higher incomes.

The most commonly used social media platforms included in the survey are YouTube and Facebook, with more than six in ten saying they use each of these platforms at least weekly. Regardless of whether they use the platforms, about half say they would have at least a little trust in information about health issues if they saw it on YouTube and four in ten say the same about Facebook. However, fewer than one in ten say they would have a lot of trust in health information seen on any of the platforms included in the survey.

Even among the those who frequently use specific social media sites, very few say they would have a lot of trust in health information if they saw it on these platforms. One in six Reddit weekly users say they would have a lot of trust in health information if they saw it on that platform, with similar shares of weekly TikTok, YouTube, and Twitter users expressing a lot of trust in health information they may see on those platforms.

Information Sources and Exposure and Belief in Health Misinformation

Similar to previous KFF surveys, this survey shows that consumption of different types of news media is correlated with belief in health misinformation. For example, when it comes to the falsehoods about COVID-19 and vaccines tested in the survey, just under half (45%) of all adults say they have both heard at least one of these falsehoods and believe it to be probably or definitely true. This share rises to about three in four among regular viewers of Newsmax, two-thirds among regular viewers of OANN, and six in ten among regular viewers of Fox News. In comparison, three in ten of those who regularly get news from NPR or the New York Times, and about four in ten who regularly get news from their local newspaper or national network news said the same.

Social media use is also correlated with being exposed and inclined to believe health misinformation. For example, a majority of those who use social media for health information and advice at least weekly say that they have heard at least one of the false COVID-19 or vaccine claims tested in the survey and think it is definitely or probably true, compared to four in ten of those who don’t use social media for health advice.

KFF also released additional analysis from the Health Misinformation Tracking Poll Pilot examining media use and trust and exposure and susceptibility to health misinformation among Black adults, Hispanic adults, and rural residents.