Copay Adjustment Programs: What Are They and What Do They Mean for Consumers?

Introduction

Americans spend on average more than $1,000 per person per year on prescription drugs, far surpassing prescription drug spending in other peer nations. According to a 2023 KFF poll, 3 in 10 adults taking prescription drugs report that they have not taken their medication as prescribed due to costs. In a 2023 KFF consumer survey, nearly one-quarter (23%) of insured adults reported that their health insurance did not cover a prescription drug or required a very high copay for a drug that a doctor prescribed, increasing to more than one-third (35%) of insured adults in fair or poor physical health. People who need specialty or brand-name medications to treat chronic health conditions such as diabetes, cancer, arthritis, and HIV are especially vulnerable to high costs, particularly considering rising deductibles over the years. In addition, plans are more likely to apply coinsurance (a percentage of the cost paid by the enrollee after meeting their deductible) than copayments (a flat dollar amount) for specialty or higher cost prescription drugs than they are for lower cost drugs, which could result in enrollees having to pay more out of pocket for these drugs.

As biologics and other specialty drugs have become increasingly available, many people who take these high-cost medications receive financial assistance from drug manufacturers to offset these high out-of-pocket costs. For people with private insurance, when applied to patient deductibles and out-of-pocket costs, this assistance can provide considerable help, but increasingly plans have applied “copay adjustment programs” that do not count these amounts toward enrollees’ out-of-pocket obligations. This issue brief provides an overview of copay adjustment programs, arguments made for and against their use, their prevalence, and federal and state efforts to address them.

Key Takeaways

- Many drug manufacturers provide copay coupons for their high-cost (often specialty) medications to encourage the use of their drugs and help offset out-of-pocket costs for consumers who use their medications. Concerned about the potential for these coupons to undermine their benefit designs and increase costs, some health plans have changed the way coupons apply to enrollee out-of-pocket obligations. The separate incentives of these two industry players can wind up putting the patient in the middle.

- With copay accumulators, the value of the manufacturer copay coupon is applied each time the prescription is filled but that value does not count toward the enrollee’s deductible or out-of-pocket maximum. Once the coupon is exhausted the enrollee is suddenly subject to their deductible and then a copayment and/or coinsurance, which can be substantial for these medications.

- The 2024 KFF Employer Health Benefits Survey found that nearly one in five (17%) large employer-sponsored health plans have a copay accumulator program in their largest plan, increasing to one-third (34%) of firms with 5,000 or more workers. Another analysis found that two-thirds (66%) of individual Marketplace plans sold in states that do not prohibit copay accumulator programs have such a program in 2024.

- With copay maximizers, insurers seek to capture the savings from coupons provided by drug manufacturers. Plans re-classify certain high-cost specialty medications such that they are no longer subject to the Affordable Care Act’s patient cost sharing limitations. Copay coupons do not count toward the enrollee’s deductible or out-of-pocket maximum. Enrollee cost sharing requirements are set to match the maximum coupon value, which is applied evenly throughout the year. Enrollees who choose to participate in the program do not typically face immediate out-of-pocket costs for that medication, but if they choose not to participate, they face substantial out-of-pocket obligations that do not count toward their out-of-pocket obligations.

- Definitive data on the prevalence of copay maximizers is limited, but one study found that their use has increased dramatically in recent years, with roughly half of commercially-insured individuals exposed to one.

- Federal regulations have not yet fully addressed the use of copay adjustment programs, but federal legislation has been introduced, and 20 states and Washington, DC, have taken action to fill these gaps for state-regulated health plans.

Overview of Manufacturer Copay Coupons

Many prescription drug manufacturers have established copay assistance programs in the form of copay cards and coupons to help offset immediate out-of-pocket costs (deductibles, copays, and coinsurance) for brand name, often specialty, prescription drugs for people with health insurance. Some branded drugs with coupons have a generic equivalent. The structure of copay coupons varies by manufacturer and by drug. Some coupons are valid for a certain number of prescription fills or for the duration that the patient is prescribed the medication. Some have a maximum annual dollar value while others have a monthly maximum, or a combination of both. Some manufacturer copay coupon programs require a relatively nominal monthly contribution (e.g., $10) from the patient toward the cost of the drug. Copay coupons can also be applied toward patient deductibles and coinsurance payments.

Eligibility may vary depending on whether the insured patient’s health insurance plan has a copay adjustment program (discussed in the next section). Copay assistance programs are different from patient assistance programs (PAPs), which typically provide financial assistance to those without insurance (or who are underinsured) who meet certain maximum income thresholds. Co-pay assistance programs are also different from drug discount cards that are available to any consumer that may provide them with a discount on a medication at a pharmacy.

Copay assistance is available for the vast majority of brand name drugs and that share has increased over time. In 2023, copay assistance was used for an estimated 19% of prescriptions for patients with private insurance (though much higher for some therapy areas), with a total value of $23 billion. Nearly one-third of brand commercial prescriptions used manufacturer copay assistance in the top 10 therapy areas that year.

The federal anti-kickback statute prohibits manufacturers from offering copay coupons for beneficiaries of federal health care programs, including Medicare and Medicaid, because coupons can act as a financial incentive for beneficiaries to choose more expensive drugs over lower-cost equivalents, which can also lead to higher federal spending. Manufacturers typically have safeguards in place to help ensure compliance with the law, such as notices printed on coupons and sent to pharmacies or verification during the claims transaction system. However, a 2014 study by the Office of the Inspector General of the Department of Health and Human Services found that these safeguards may not prevent all copay coupons from being used to pay for Medicare Part D drugs, in part because coupons are not always transparent in the pharmacy claims transaction system to entities other than manufacturers and manufacturers could be relying on unreliable patient information.

By contrast, federal laws that apply to private insurance, such as the Affordable Care Act (ACA), do not specifically address copay coupons. The ACA does, however, place annual limits on out-of-pocket cost sharing for covered essential health benefits (EHBs), including prescription drugs, for consumers with private insurance (see callout box). At least two states (MA (until 2026) and CA) prohibit the use of copay coupons in their state-regulated private insurance markets if the drug has a generic equivalent, with some specific exceptions.

Essential Health Benefits (EHBs)

What are they? A set of 10 categories of services that certain health insurance plans must cover under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), including prescription drug coverage, doctors’ services, hospital care, pregnancy and childbirth, mental health services, and more. Plans subject to EHB requirements must cover of at least as many prescription drugs in every category and class in the U.S. Pharmacopeia Medicare Model Guidelines as covered by the state’s EHB-benchmark plan, or one drug in every category and class, whichever is greater.

What types of health plans must cover the EHBs? Non-grandfathered, ACA-compliant plans sold in the individual and small group markets.

What types of health plans do not have to cover the EHBs? Large group plans (whether fully-insured or self-funded) and self-funded small group plans. However, if these plans opt to cover any EHBs, and most do, they must count cost-sharing amounts toward the plan’s annual out-of-pocket maximum. Agency regulations require plans to choose a state benchmark plan to determine what services count.

How do manufacturer copay coupons work?

To explain how manufacturer copay coupons work in practice, consider the following hypothetical scenarios in which a patient, who takes a brand-name, specialty medication to treat her cystic fibrosis that costs $2,000/month, does and does not receive a copay coupon (Table 1). Assume the patient, whose plan year begins in January, has a:

- $2,000 deductible which she has not yet met,

- 25% coinsurance (which equates to $500),

- $5,000 out-of-pocket (OOP) maximum, and

- A $6,000/year manufacturer coupon, when applied.

Without a copay coupon: The patient pays the full cost of the medication in January after which point her deductible has been met. The insurance plan begins to cover the drug in February and the patient pays her required coinsurance. In July, she reaches her OOP maximum ($5,000) and the plan covers in full her cystic fibrosis medication (and all other covered health care services and medications received in-network) for the remainder of the plan year.

With a copay coupon: The patient’s copay coupon is applied to her deductible and coinsurance each month. In this scenario, her $5,000 OOP maximum is met in July, meaning that even though the coupon was for $6,000, the manufacturer ends up paying $1,000 less. Her health plan will now cover the drug in full for the remainder of the year. The patient pays $0 for this medication over the course of the plan year. The health plan receives no benefit from the copay coupon.

In both scenarios, the patient reaches her deductible and OOP maximum in the same month. The total cost sharing amounts paid are the same in both scenarios; however, in the scenario without a coupon, that amount is shifted from the patient to the drug manufacturer.

Issue Brief

Overview of Copay Adjustment Programs

A ‘copay adjustment program’ is an umbrella term that includes various pharmacy benefit designs that allow enrollees to use manufacturer copay coupons at the point-of-sale but ensure that only amounts paid by the enrollee count toward their deductible and out-of-pocket maximum. Two common types of copay adjustment programs are copay accumulators and copay maximizers, though plans may refer to them in different terms, such as patient assurance programs out-of-pocket protection programs, and variable copay programs. While some copay adjustment program features may vary slightly from plan to plan, and some hybrid models do exist, these programs commonly include the following characteristics (Table 2):

As mentioned above, the use of copay coupons is not always evident in pharmacy claims transaction systems to entities other than manufacturers. Many plans require specialty medications to be filled through the PBM’s specialty pharmacy in an effort to reduce costs. (The three largest PBMs are vertically integrated with health insurers and specialty pharmacies.) This requirement may also provide a better opportunity for plans/PBMs to detect when a coupon is being used to pay for a medication. In addition, because large and self-insured employer plans that are not required to cover the EHBs are still required to have out-of-pocket maximums, and to select a state benchmark plan on which to base those amounts, copay maximizer vendors often encourage plan sponsors to select a state EHB benchmark plan that requires the fewest number/classifications of drugs to be covered.

How Copay Adjustment Programs Work: Example Scenarios

To explain how copay adjustment programs work in practice, consider the following hypothetical scenarios (Table 3) using the same assumptions as above:

With a copay coupon and a copay accumulator program: The patient still receives the copay coupon for her medication, but that assistance no longer counts toward her deductible or OOP maximum. The coupon pays the full cost of the medication until it has been exhausted in March. The patient then begins paying toward their deductible, which she reaches in April, and then her coinsurance until she reaches her OOP maximum, in October.

With a copay coupon and a copay maximizer program: The patient’s cost-sharing requirements are set to the full annual value of a copay coupon, which is applied evenly throughout the year such that she is not subject to a sudden deductible payment after the coupon has been exhausted (as is the case in the copay accumulator example). The manufacturer coupon covers all her cost sharing for this medication for the plan year; however, the patient does not satisfy any of her deductible or reach her OOP maximum unless she is paying for other covered benefits that count toward these cost-sharing requirements.

As demonstrated in these hypothetical scenarios, the patient receives the greatest direct benefit from the coupon without a copay adjustment program (Table 4). She meets her deductible and OOP maximum in the same months as she would have without having a copay coupon (January and July, respectively), but she pays less. In the copay accumulator scenario, the patient pays the same OOP costs as she would have without a manufacturer coupon ($5,000) but her deductible and OOP maximum are not met until later in the year (April and October, respectively). Under the copay maximizer scenario, she pays $0 out-of-pocket for her medication, like she would without a copay adjustment program, but she does not reach her deductible or OOP maximum during the plan year from this medication alone.

With a copay accumulator, the health plan reaps the vast majority of the benefit of the drug manufacturer coupon, shifting costs back to the consumer. With a copay maximizer, the health plan recaptures some of the benefit of the coupon.

Outside of these hypothetical scenarios, it should be noted that generally:

- Patients, especially those with chronic conditions requiring expensive medications, may use other covered medical services or prescription medications during the plan year, which may affect their out-of-pocket costs and when during the plan year they reach their OOP maximum.

- Some plans begin covering certain prescription medications before the deductible has been met.

- In the case of a copay maximizer program, the third-party program a patient is enrolled in to administer the maximizer program may be able to secure a higher value copay coupon and set the patient’s cost sharing obligation to that amount, which could result in higher cost sharing than otherwise would have been required.

- Sometimes, though not always, a medically appropriate, generic equivalent is available that costs less than the branded drug, which could result in lower out-of-pocket costs even without a manufacturer coupon.

Arguments For and Against Copay Adjustment Programs

The advantages and disadvantages of copay adjustment programs vary by stakeholder, with drug manufacturers, patients, and patient advocacy groups generally opposing such programs, and health plans/sponsors defending their use. The following discussion summarizes many of these arguments and industry incentives.

Drug Manufacturers

There are several business reasons manufacturers may choose to offer coupons, including to enhance brand loyalty and promote the use of their drug over others, and to compete for market share when generic drugs enter the market. (As previously mentioned though, these coupons are not permitted in public programs such as Medicare.) Manufacturers argue that this assistance helps patients afford needed medications. They contend that copay adjustment programs undermine that assistance and threaten the availability of patient assistance for those it is intended to help. Manufacturers and patients/patient advocacy groups are often aligned in their criticism of copay adjustment programs. Some manufacturers have taken action to address plans’ use of these programs (discussed in more detail later).

Health Plans/Sponsors

As health plan sponsors explore options to address increasing prescription drug prices, they (and sometimes their third-party vendors) argue that copay adjustment programs are a valuable tool to help reign in health care costs and that copay coupons circumvent formulary designs intended to steer enrollees to higher value, lower-cost medications. They state that manufacturer discount programs incentivize patients to choose brand-name, higher-cost drugs instead of generic, lower-cost drugs, which could, in turn, increase premiums, and that manufacturers benefit from coupons by taking advantage of federal tax deductions for charitable donations for the cost of the coupons. One study of one state’s commercial insurance market found that drug coupons for certain branded drugs with a generic equivalent increase utilization and spending, which could increase premiums.

Third-party vendors that administer copay adjustment programs report that their programs result in reduced specialty drug claims and significant savings for employers. Insurers also contend that the manufacturer assistance programs encourage manufacturers to keep drug prices high, pointing to studies that have confirmed some of these claims. There are concerns that plans may simply be capturing these assistance dollars intended for patients. Insurers have disputed claims that copay adjustment programs allow health plans/PBMs to “double dip,” which refers to plans essentially collecting two deductibles (one from the manufacturer and one from the patient), and capturing both manufacturer drug rebates and assistance dollars, asserting that manufacturer coupons do not get directed to the plans and that the plan still pays the pharmacy the negotiated rate. (The typical flow of money for prescription drugs is complex and many factors, including manufacturer rebates paid to PBMs and the potential passthrough of savings from PBMs to plan sponsors, play a role in determining health plan profitability, though these market dynamics are beyond the scope of this brief.)

Patients/Patient Advocacy Groups

Patient advocacy groups have challenged the use of copay accumulator programs and advocate for policies that require health insurers to apply manufacturer cost sharing assistance to the enrollee’s out-of-pocket maximum. Opponents of copay adjustment programs contend that many patients with chronic illnesses rely on copay coupons to afford expensive specialty medications such as those used to treat HIV and hepatitis. The exclusion of this financial assistance from patients’ deductibles and out-of-pocket maximums, they argue, places an unfair cost burden on these patients and can lead to reduced medication adherence particularly with copay accumulator programs. (It should be noted that many of the patient advocacy groups speaking out against these programs are funded at least in part by pharmaceutical companies.)

Additionally, opponents of copay adjustment programs state that many of the brand name drugs that chronically ill people use do not have a generic version and that, when available, generics are not always substantially cheaper than the brand name or therapeutically equivalent or appropriate for the specific patient. Furthermore, one study found that although White and “non-White” patients utilize copay coupons at similar rates, non-White patients are more likely than White patients to face copay adjustment programs (though the reasons for this are not clear), which could exacerbate racial and ethnic disparities in access to medications. Copay maximizers have also been accused of artificially inflating cost sharing amounts to match the amount of assistance, and criticized as coercive to patients and lacking in transparency.

Prevalence of Copay Adjustment Programs

While definitive data on the prevalence of programs designed to blunt the financial impacts of manufacturer assistance are limited, there has been some research that can help quantify the extent to which commercial health plans employ and enrollees are exposed to these programs.

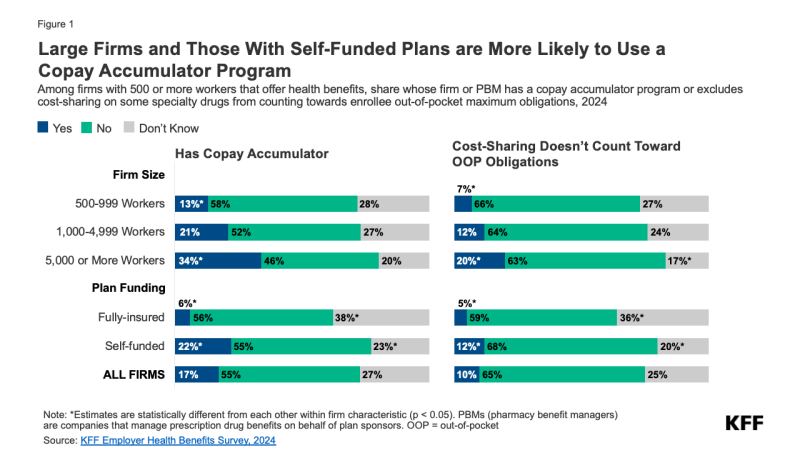

According to the nationally-representative 2024 KFF Employer Health Benefits Survey, among firms with 500 or more workers offering health benefits, nearly one-fifth (17%) have a copay accumulator program (including programs administered through the PBM) in their plan with the largest enrollment (Figure 1). This share increases to 34% for firms with 5,000 or more workers, compared to 13% for firms with 500-999 workers. About one-quarter (27%) of firms are unsure if their largest plan has a copay accumulator program. Firms with self-funded plans are more likely than those with fully-insured plans to offer a plan with a copay accumulator program (22% vs. 6%). (On average, larger firms are more likely to be self-funded than smaller firms.)

Although not a copay adjustment program per se, some health plans exclude cost sharing for certain medications from counting toward the enrollee’s out-of-pocket maximum which, as discussed below, new federal regulations aim to prevent. To better understand the extent to which this practice is occurring, the Employer Health Benefits Survey also asked large firms whether their largest health plan excludes cost sharing on any specialty drugs toward enrollees’ out-of-pocket maximum obligation. Overall, 10% of firms with 500 or more workers that offer health benefits report having this plan feature, increasing to 20% of the largest firms (Figure 1). Twelve percent of firms with self-funded plans have this feature, compared to 5% of firms with fully-insured plans. One-quarter (25%) of firms do not know if their plan has this feature.

With so many survey respondents, who are generally human resources or benefits managers, not knowing whether their plan has one of these plan features, plan enrollees also may not be aware of their plan’s coverage policy for certain medications. This lack of awareness presents an opportunity for increased health plan transparency and firm and enrollee education about their pharmacy benefit designs.

The KFF survey did not ask about copay maximizer programs specifically, but according to another organization’s 2023 survey of a convenience sample of 35 PBMs and payers representing nearly 118 million enrollees with private coverage, half (49%) of those enrollees covered by these respondents were in a plan that had implemented a copay maximizer program for at least some covered drugs, an approximately eight-fold increase since 2018 (Figure 2). This sharp increase could reflect plan sponsors’ desire to cut their costs further than copay accumulator typically can, while still allowing enrollees to benefit from manufacturer assistance. However, respondents to this survey reported that their enrollees are now just as likely to be in a plan with copay maximizer program as they as with an accumulator. Health plans may use one or both of these copay adjustment programs.

A review of ACA Marketplace plans conducted by a patient advocacy group found that among states that do not prohibit copay accumulator programs, two-thirds (66%) of plans sold on those Marketplaces in 2024 have a copay adjustment program (not including the 16 plans that have a copay accumulator adjustment policy that only applies to brand name drugs that do not have a generic alternative) (data not shown).

The share of enrollees with private coverage exposed to copay adjustment programs varies by certain therapeutic areas, ranging from 11% for autoimmune medications to 18% for multiple sclerosis and oncology medications in 2023, as another study of 23 specialty brands and biosimilars in commercial claims data found (data not shown).

Manufacturer Response

As plan sponsors’ use of copay adjustment programs continues to proliferate, drug manufacturers have taken notice, and at least one has responded by filing a lawsuit against vendors of copay maximizer programs.

For example, in 2022, manufacturer Johnson & Johnson filed a lawsuit against SaveOnSP (a vendor that administers a copay maximizer program for Cigna’s PBM, Express Scripts), accusing SaveOnSP of deceptive trade practices and exploiting its copay assistance program in violation of its terms and conditions. The lawsuit states that because of SaveOnSP, Johnson & Johnson has paid millions more in copay assistance than it otherwise would have and for a purpose it did not intend. The case is ongoing.

Some drug manufacturers have responded by changing their copay assistance programs, which could inadvertently put patients in the crosshairs of the battle between health plans and manufacturer assistance programs. For example, Pfizer updated the terms and conditions of its copay assistance program to state that the program is not available to patients in plans with a copay accumulator or adjustment program. Other manufacturers, such as Vertex, which manufactures a cystic fibrosis medication, have reduced the value of their copay coupons when a plan/PBM is using a copay adjustment program.

Federal and State Actions

As health plans’ use of copay adjustment programs have increased in recent years, so too, have federal regulations, lawsuits, and state laws.

Federal

The HHS Notice of Benefit and Payment Parameters (NBPP) for 2020 could be read to permit private plans to use copay accumulators only when the drug has a “medically appropriate,” generic equivalent, as permitted by state law. The NBPP for 2021 reversed that provision, providing that, when consistent with state law, health plans/PBMs could opt to decline to credit copay coupons towards enrollee cost sharing obligations, regardless of whether a generic equivalent was available, citing potentially conflicting regulations regarding the tax treatment of high-deductible health plans paired with a health savings account.

However, in 2022, patient advocacy groups filed a lawsuit challenging that portion of the 2021 rule. In 2023, a U.S. District Court ruled in favor of the plaintiffs and vacated the 2021 copay accumulator rule in part because it conflicted with the ACA’s definition of “cost sharing,” concluding “that the regulatory definition unambiguously requires manufacturer assistance to be counted as “cost sharing,” which is “any expenditure required by or on behalf of an enrollee.” A later decision clarified that because the 2021 copay accumulator rule was vacated,” plans have to adhere to the 2020 rule. However, in its 2023 motion to clarify, HHS stated that it would not take enforcement action against issuers or plans that do not count manufacturer assistance for drugs that have generic equivalents toward out-of-pocket obligations and that it intended to issue a new final rule. HHS has withdrawn its appeal of the decision. A new rule specifically addressing the definition of cost sharing or the treatment of copay adjustment programs has not yet been issued.

In response to concerns about plan sponsors reclassifying certain drugs as “non-EHB” and not counting enrollee cost sharing for these drugs to count toward out-of-pocket maximums, the 2025 NBPP explicitly requires non-grandfathered individual and fully-insured small group plans that cover prescription drugs in excess of the state’s benchmark plan (with limited exceptions) to consider those drugs part of its essential health benefits (EHB) package and clarifies that plans are required to count these amounts toward the required annual limitation on cost sharing. The final rule states that the Departments intend to propose rulemaking that would also make these standards applicable to large group plans and self-funded plans.

In 2023, a bipartisan group of federal lawmakers introduced the Help Ensure Lower Patient (HELP) Copays Act, which would require plans/PBMs to apply copay coupons to enrollees’ out-of-pocket obligations. It also stipulates that health plans that cover drugs must consider all covered drugs part of its essential health benefits package, which are required by the Affordable Care Act to count toward an enrollee’s out-of-pocket maximum for individual and small group market plans. If passed, the law would apply to all private health plans including those that are self-funded, thereby filling a substantial gap in state copay accumulator laws. The legislation has not yet been brought to a vote.

Also of note, the Federal Employees Health Benefits (FEHB) Program, which covers millions of federal workers and their dependents, does not permit the plans it contracts with to use copay maximizers or other similar programs, asserting that these types of benefit designs are not in the best interest of enrollees or the federal government.

State

There has been increasing interest at the state level in recent years to address the use of copay accumulator programs, with 20 states and the District of Columbia restricting them in their state-regulated health plans/PBMs. Eleven of those states prohibit accumulator programs only if a generic equivalent is available and the others ban them in all cases (Figure 3). Beginning in 2025, Nevada and Oregon will also require their state-regulated health plans to count drug manufacturer financial assistance toward the enrollee’s cost sharing limits if there is no generic available.

State insurance laws, including prohibitions on copay accumulator programs, only apply to state-regulated health plans and not to self-funded plans sponsored by private employers, which cover 63% of covered workers at private firms nationally. There is some variation by state, ranging from 35% of covered workers in Hawaii to 73% in Nebraska (Figure 3). Among the 25 states where a higher than average share of adults has multiple chronic health conditions, 13 restrict the use of copay accumulators in their state-regulated health plans (Figure 3), perhaps reflecting an interest among state legislators and patient advocates to shield these populations, who may rely on more expensive medications, from high out-of-pocket costs. No state laws have yet directly addressed copay maximizer programs.

Federal policies could affect state policies on copay adjustment programs. If the state laws conflict with federal laws and regulations, there are arguments that the state law is preempted.

Looking Forward

State and federal efforts to address the use of manufacturer financial assistance are part of broader efforts to limit patient drug costs. These efforts coincide with changes to Medicare drug pricing, state laws limiting cost sharing for insulin, as well as litigation related to these efforts, all amid increasing concerns about medical debt. In a 2024 KFF public opinion poll, just over half (55%) of U.S. adults reported worrying about being able to afford prescription drug costs; and according to a 2023 KFF poll, nearly three in ten (28%) said they have difficulty affording their prescriptions.

Studies show that reducing copayments results in better adherence to needed medications and better health outcomes and that manufacturer financial assistance can help promote this. However, counting this assistance toward patient out-of-pocket obligations could limit the ability of plans to steer patients to lower cost drugs and drive up costs for plan sponsors and, in turn, premiums paid by all consumers.

Entering this landscape is a relatively new approach to funding high-cost specialty medications called “alternative funding programs” (AFPs). These programs are being increasingly marketed to employers as a way to lower their costs by shifting the financial responsibility for these drugs to alternative funding sources such as patient assistance programs (PAPs) established by pharmaceutical companies and charitable organizations. To do this, some or all specialty medications are removed from the plan’s formulary, and patients, who now appear to be uninsured or underinsured, are enrolled in a PAP that pays for the drug. Data on the prevalence of these programs is limited, but their practices are already under scrutiny.

Although federal regulations in recent years have sought to address the use of copay accumulator programs, there still is no definitive policy, and they have not yet addressed newer models such as copay maximizers and alternative funding programs. Many states have taken action to fill gaps in federal policies related to copay accumulators, but most have also not caught up with the use of these newer models and their reach is limited to state-regulated health plans.

The outcome of a lawsuit decided by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2024, Loper Bright, could have new, far-reaching implications for federal regulations. Regulations related to any number of policy areas, including those that address the use of copay adjustment programs and alternative funding programs, could be subject to increased legal scrutiny as courts are no longer required to defer to agency decisions where federal law is silent or unclear.

While laws and regulations address prescription drug costs to some extent in Medicare (e.g., out-of-pocket caps on insulin) and Medicaid (e.g., drug rebates to states and the federal government), prescription drug costs in the private insurance market are largely unregulated. Drug manufacturers have the ability to set high prices, particularly for drugs still under patent protection, and then provide financial assistance directly to privately-insured patients, which can increase their market share. Health plans, in an effort to control costs, then try to recapture that financial assistance. In the meantime, patients are caught in the middle of these market dynamics shouldering the consequences.

This work was supported in part by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The views and analysis contained here do not necessarily reflect the views of the Foundation. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism.