The U.S. Government Engagement in Global Health: A Primer

Published:

Introduction

Attention to global health by governments, policymakers, media, business leaders, and other institutions has increased markedly in recent decades, with a particular focus on health challenges facing low- and middle-income countries. This has led to growing funding, the establishment of new institutions and global goals, and a burgeoning community of stakeholders.

The U.S. government has long supported health programs as an element of foreign aid and development assistance, and is the largest donor to global health. These programs have grown in size and prominence over time, most notably with the launch of the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and the President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI), and the U.S. government support of the creation of the multilateral organization, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (the Global Fund), in the early 2000s. Today, the U.S. government remains the largest funder and implementer of global health programs worldwide, and global health remains the largest component of U.S. foreign assistance, although funding has leveled in recent years. In addition, the current Administration has proposed to reduce the U.S. global health budget and pull back from multilateral engagement, creating questions about the future of U.S. support.

The U.S. global health response is complex, a multi-pronged, multi-billion dollar investment involving many different U.S. government departments and agencies, congressional committees, initiatives, and funding streams and targeting a myriad of global health challenges and countries.1 This primer provides basic information about global health and the U.S. government’s response in low- and middle-income countries. Although it focuses primarily on the U.S. government, it is important to acknowledge the role played by other countries, multilateral organizations, and private sector actors, such as non-governmental organizations (NGOs), foundations, corporations, and others, in the global health response.

The first several sections of this primer provide an overview of the field of global health and describe current global health issues. Subsequent sections describe U.S. government support for global health, including the programs addressing global health challenges, the organization of the U.S. response, the budgets and financing of U.S. global health programs, and the U.S. government’s relationship with multilateral institutions and international partners. More global health policy resources, information, and analysis from KFF are available online.

Report

What is Global Health?

Despite a growing emphasis on the importance of addressing global health by the international community and the U.S., there is currently no standard, agreed-upon definition for global health, and several different definitions exist. The Institute of Medicine has defined global health as having “the goal of improving health for all people in all nations by promoting wellness and eliminating avoidable diseases, disabilities, and deaths.”1 It has also been defined as “public health for the world”, focusing on the health of populations rather than the health of individuals, and as emphasizing “transnational health issues, determinants, and solutions…a synthesis of population based prevention with individual-level clinical care.”2,3

| Box 1: Definitions of Key Global Health Measures |

| Prevalence – the number of people with a particular condition at any given time (e.g., the number of people who are HIV positive).

Incidence – the number of new cases of a disease or condition in a population within a period of time (e.g., the number of people who became newly infected with HIV in a year). Mortality – deaths; can reference overall mortality (i.e. from all causes) or deaths due to a particular disease or condition (e.g. deaths from HIV/AIDS) or deaths in a particular population (e.g. child deaths). |

The field of global health has evolved out of the historical disciplines of “tropical medicine” and “international health,” but what sets global health apart from these prior eras is a recognition that the health of people around the world is highly interconnected, with domestic and foreign health inextricably linked.4,5 A key dimension of global health is an emphasis on addressing inequities in health status between rich and poor populations. Persons in low- and middle-income countries face lower life expectancies and higher burdens of disease, and are disproportionately affected by certain highly preventable causes of disease and mortality compared to persons in high-income countries. In low-income countries, preventable deaths from infectious diseases (such as respiratory infections, diarrheal diseases, HIV/AIDS, and malaria) are among the most common killers. In contrast, the most common causes of deaths in high-income countries are from chronic, non-communicable diseases (such as heart disease, stroke, cancer, and diabetes), although the burden of chronic, non-communicable conditions is growing in low- and middle-income countries.

Current Global Health Challenges

There are many factors that contribute to inequities in health, and persons in low- and middle-income countries face many different kinds of health challenges. Some of the broader conditions that lead to poor health, or the “social determinants of health,” include poverty; lack of education; lack of access to clean water, sanitation, and food; environmental conditions; and weak health systems. While many global health efforts seek to address and impact these larger determinants of health, more commonly they are directed toward more specific issues or causes of disease. Some of the most prominent issues and diseases targeted by global health efforts include:

HIV/AIDS – Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is the virus that causes acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), the most advanced stage of HIV infection. People become infected with HIV primarily through sexual contact with an infected person, though it can also be transmitted through blood (e.g., by using a syringe that has been previously used by someone who is infected) or from a mother to a baby during pregnancy, delivery, or breastfeeding. HIV weakens the immune system, leaving those affected vulnerable to opportunistic infections and potentially death. Although there is no cure or vaccine, HIV can be effectively treated with antiretroviral therapy. In addition, numerous prevention interventions exist to combat HIV, such as behavior change programs, condoms, blood supply safety, harm reduction efforts for injecting drug users, PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis with antiretrovirals), and male circumcision. Further, research shows that HIV treatment not only improves individual health outcomes, but also significantly reduces the risk of transmission.6 – those with undetectable viral loads (known as being virally suppressed) have effectively no risk of transmitting HIV sexually.7 Access to prevention and treatment programs, however, remains limited in many areas. Sub-Saharan Africa, where it is estimated that approximately 70% of all people living with HIV are, faces the highest burden of disease from HIV. Additionally,

70% of all AIDS deaths occur in this region.8

| Box 2: HIV/AIDS |

|

Tuberculosis – Tuberculosis (TB) is an airborne infectious disease caused by bacteria that primarily affects the lungs. While active TB can be spread from person to person and is a major cause of illness and death around the world, TB can remain latent in otherwise healthy people, who exhibit no symptoms and cannot transmit the bacteria to others. In addition, it is a common and serious threat to people with compromised immune systems, such as those living with HIV. No effective vaccine currently exists to prevent transmission of TB, although the BCG (Bacillus Calmette-Guérin) vaccine is partially effective in preventing some serious TB complications in children; other vaccines are currently being developed.9 TB control programs around the world commonly use a method called DOTS, or “directly observed treatment, short-course” to treat and prevent TB using a combination of drugs. As a result of inconsistent or partial treatment, incorrect prescribing, or interruptions in the drug supply, TB that is resistant to commonly used drugs has emerged as a major challenge for TB control efforts. Thirty countries, all of which are low- and middle-income, are considered “high-burden countries (HBCs),” accounting for approximately 87% of new TB cases each year.10

| Box 3: Tuberculosis |

|

Malaria – Malaria is a parasitic disease that is spread to people through the bite of a particular mosquito species, known as Anopheles, which thrive in warm tropical and sub-tropical climates. Symptoms of malaria include fever, vomiting, and diarrhea, and in severe cases it leads to death. Malaria control efforts involve a combination of prevention and treatment strategies and tools. Prevention strategies include use of insecticide-treated bed nets and indoor residual spraying for mosquito control, and the use of drugs to prevent infection. A malaria vaccine is not yet available, although clinical trials are underway. Drugs for treating malaria include: chloroquine, primaquine, and artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs). Drug resistance is an important issue in malaria, as the parasite has developed resistance to common anti-malarial drugs in some areas. While access to malaria prevention and treatment services in affected areas has grown over time, gaps remain. Sub-Saharan Africa is the hardest hit region in the world.11,12

| Box 4: Malaria |

|

Neglected Tropical Diseases – Neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) are a group of parasitic, bacterial, and viral infections that primarily affect the most impoverished and vulnerable populations in the world. They are called NTDs because until recently they had received only scant attention in global health efforts. More than one billion people, almost all of whom live in low- and middle-income countries, are infected with one or more NTDs, and another 2 billion people are at risk.13 The U.S. targets several NTDs, including worm infections such as roundworm and hookworm, lymphatic filariasis (a parasitic infection transmitted by mosquitos), schistosomiasis (a parasitic infection transmitted by fresh water snails), onchocerciasis (also known as river blindness), and trachoma (a bacterial infection that can cause blindness), as highly cost-effective treatment and prevention tools, including mass drug administration, are currently available to address them.14

Family Planning and Reproductive Health – Family planning is the ability of a person or family to plan for and attain the desired number of children as well as the desired spacing and timing of births. Reproductive health is the state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being in all matters relating to the reproductive processes, functions, and system at all stages of life.15 Access to family planning and reproductive health (FP/RH) services is critical to the health of women and children worldwide because these services are effective in decreasing the risk of unintended pregnancies, maternal and child mortality, and other complications.16,17 FP/RH education and services support birth spacing, contraception, counseling, post-abortion care, screening/testing for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), repair of obstetric fistula, antenatal and postnatal care, and human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines to prevent cervical cancer and genital warts. Novel FP/RH tools, such as microbicides (compounds that can be inserted into the vagina or rectum to protect against STIs), are also being pursued. Approximately 12% of women developing countries have an unmet need for family planning.18

| Box 5: FPRH |

|

Maternal and Child Health – Maternal and child health (MCH) programs address the health needs of mothers before and during pregnancy and childbirth, as well as the health of newborns and young children. Ninety-nine percent of maternal deaths and deaths in children under 5 occur in the developing world.19,20,21,22 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), most maternal deaths are preventable through “quality family planning services, skilled care during pregnancy, childbirth and the first month after delivery, or post-abortion care services and where permissible, safe abortion services.” Addressing health care for newborns and young children focuses on care during pregnancy, safe delivery, neonatal care, and breastfeeding, as well as prevention and treatment of diseases and conditions such as pneumonia, diarrhea, malaria, HIV/AIDS, and malnutrition. There are many low-cost prevention and treatment measures – such as immunization, antibiotics, insecticide treated bed nets, zinc supplements, and oral rehydration therapy – that can reduce infant and child mortality and improve their health.

| Box 6: MCH |

|

Polio – Poliomyelitis, or polio, is a crippling and sometimes fatal viral disease. Polio is transmitted through the fecal-oral route, and enters the body through the mouth when people eat food or drink water contaminated with excreta. The virus is easily spread in areas with poor hygiene and mainly affects children under five years of age. Polio cannot be cured, but is preventable through vaccination. A global effort to completely eradicate the disease began in 1988, and since then the number of polio cases has dropped over 99% worldwide. The eradication effort continues today, but three countries – Nigeria, Pakistan, and Afghanistan – have not been able to interrupt polio transmission and remain endemic for the disease, and outbreaks of the disease continue to occur in other low-income countries.23,24 Polio could surge again if eradication is not completed and control measures are scaled back.

| Box 7: Polio |

|

Nutrition – Poor nutrition comes in various forms and is typically characterized by inadequate or excess intake of protein, energy, and micronutrients such as vitamins. Undernutrition, a lack of the nutrients needed by the body for appropriate growth and development, can result from an inadequate food supply or from insufficient intake of certain types of food (e.g., protein and micronutrients), and is especially prevalent in populations in low- and middle-income countries. Undernutrition increases the risk of certain diseases and can lead to premature death, especially in infants and children. Nutrition interventions include breastfeeding promotion, infant and young child feeding programs, micronutrient supplementation (e.g., vitamin A), food fortification, and improving food security.25 Almost all of the approximately 815 million undernourished people in the world live in developing countries.26,27

| Box 8: Nutrition |

|

Water and Sanitation – Lack of clean water and sanitation access can lead to exposure to a variety of pathogens that can cause illnesses, especially diarrhea. Children – in particular those with already poor health and nutritional status – are very susceptible to dehydration from diarrhea. Treatment of diarrhea centers around fluid replacement to prevent dehydration (e.g., using a solution of oral rehydration salts). In addition, zinc may be provided, since episodes of diarrhea may create a deficiency of the mineral in the body that is associated with higher rates of infectious diseases and mortality. Prevention involves improved access to water and sanitation, exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life, and promotion of hand-washing with soap. Only 62% of people living in developing countries have access to improved sanitation facilities compared to 96% of developed countries.28,29

| Box 9: Water and Sanitation |

|

Other Challenges in Global Health – A number of other issues are receiving increasing attention within global health. Non-communicable diseases (NCDs), particularly cardiovascular disease, cancer, chronic lung disease, and diabetes, which have historically been seen as primarily health problems of the developed world, are now seen as increasingly important contributors to the burden of disease of developing countries that should receive greater attention from global health efforts. Similarly, mental health conditions, such as depression, are increasingly being seen as an important health issues for developing countries.30,31,32 Finally, recent infectious disease threats, like Zika, Ebola,33,34 and antimicrobial resistance, have contributed to global health security gaining traction as a key issue in global health.

| Box 10: Impacts of the 2014-2015 Ebola Outbreak |

|

What Has Been the International Response to Global Health Challenges?

There is a long history of international efforts to tackle health issues. In the mid-1800s, for example, a group of countries began to negotiate international agreements on how to combat cross-border outbreaks of infectious diseases such as cholera and yellow fever.35 After World War II, international efforts expanded with the establishment of the United Nations and its health-focused agencies such as WHO and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), and with new challenges, new agencies have formed, such as the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Cooperative efforts in global health have grown significantly since the early 2000s, as new international goals and targets for addressing health challenges have been established, new global health funding vehicles and initiatives created, and the amount of funding increased.36

Key Stakeholders in Global Health

There are a diverse set of stakeholders involved in efforts to improve global health. These include multilateral and international organizations, donor and partner governments, the private sector, research organizations, civil society, academia, and individuals.37 Donor governments channel support for global health programs either bilaterally (i.e., giving their support directly to or on behalf of another country) or multilaterally (i.e., giving their support to a multilateral organization, which channels the funds to support global health programs in recipient countries). The private sector, civil society, academia, and research organizations are other important partners in global health programs. Low-and middle-income country governments (typically recipients of donor support but increasingly providing their own support for the health of their populations), local organizations, and individuals are also key stakeholders in determining how global health programs are funded and implemented. With these numerous stakeholders and multiple initiatives in the field of global health, coordination between actors remains a key challenge in the international response.

Key Global Health Milestones

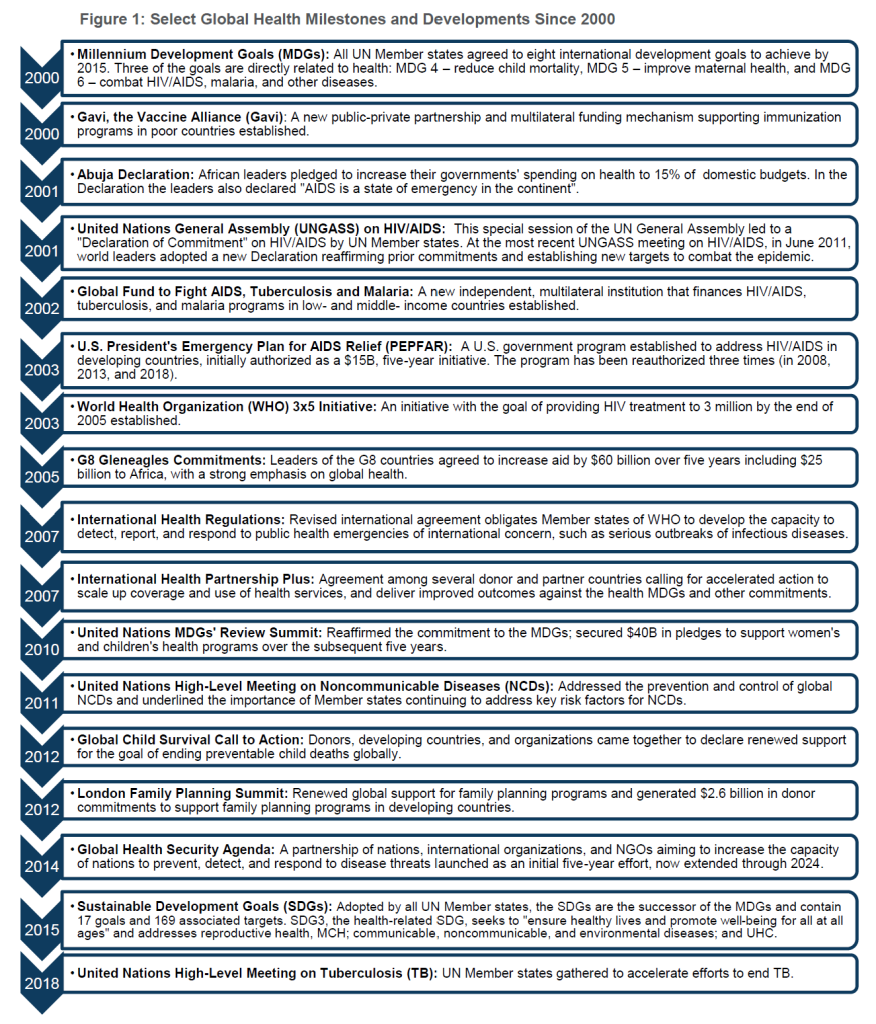

While there are several historical markers and milestones in global health, including the International Sanitary Conventions beginning in the 1800s, the founding of WHO in 1948, and the Alma-Ata Declaration of 1978 focused on primary health care, there has been a notable increase beginning in the twenty-first century.38 Since 2000, a number of treaties, commitments, partnerships, and other multilateral agreements addressing health have been supported by the international community, some of which have turned out to be important and durable milestones, while others have been less so. Figure 1 highlights some of the more important developments in international cooperation on global health.

Donor Funding for Global Health39,40

Donor government funding, including both the bilateral funding given directly to other countries (which may be given to a country government or provided to NGOs and other organizations to carry out work in recipient countries) and the multilateral funding given indirectly through contributions to multilateral organizations, accounts for most external health aid channeled to the developing world. As such, this donor support constitutes a major component of the global health response.

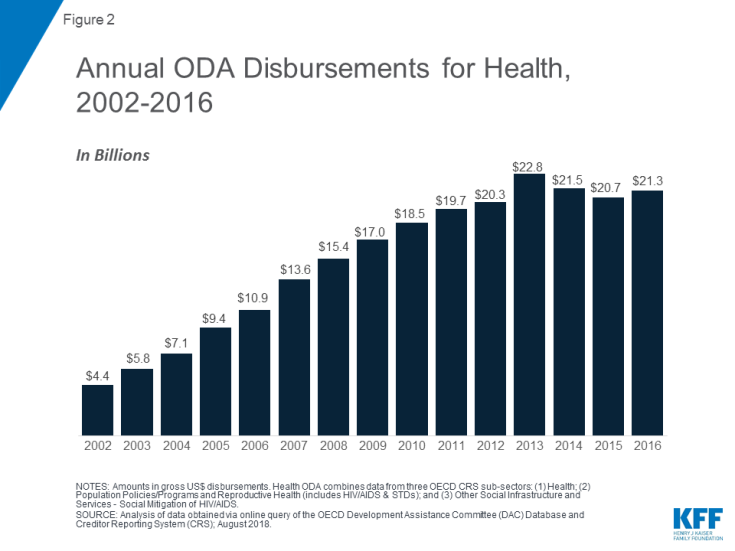

Donor government funding for global health has risen significantly since 2002, growing from $4.4 billion to a peak of $22.8 billion in 2013 (see Figure 2). However, funding declined for the first time in 2014 to $21.5 billion and has since remained relatively flat.

In addition, donor government funding for health has generally increased as a share of official development assistance (ODA), particularly over the last decade. These increases were largely spurred on by the creation of several new funding initiatives and mechanisms such as the Global Fund and PEPFAR. However, this share has remained essentially flat in more recent years and declined in 2014 and 2015. This flattening and recent decline has raised concerns about the ability of countries to meet global health goals and targets, such as those of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).”41,42

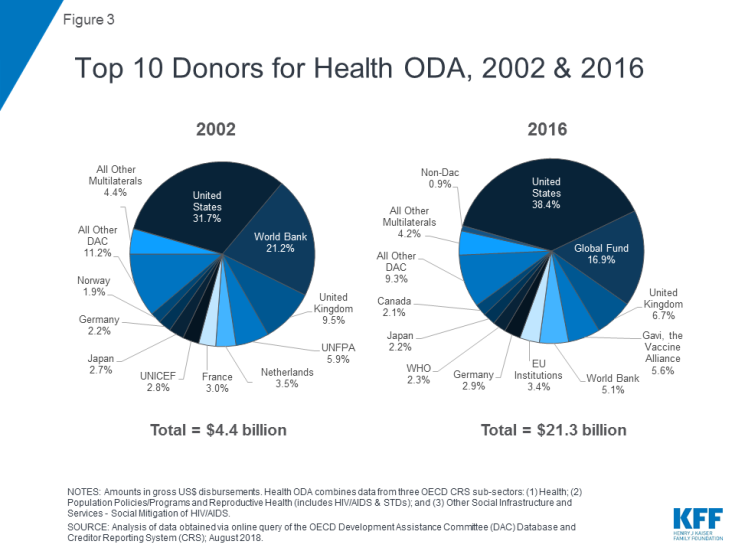

The U.S. has been the largest donor to health in each year over the entire period between 2002 and 2016, and has dedicated the greatest share of its ODA to health.43 The donor mix has shifted over this time, in part due to the entrance of new donors, particularly the Global Fund, which became the second largest donor to health after the U.S. in 2006 (and remains so today). The U.S. and the Global Fund combined accounted for more than half of total donor funding for health in 2016 (see Figure 3).

What Is The Role And Scope Of U.S. Government Support For Global Health?

U.S. global health efforts aim to help improve the health of people in developing countries while also contributing to broader U.S. global development goals (e.g., advancing a free, peaceful, and prosperous world), foreign policy priorities (e.g., promoting democratic institutions, protecting U.S. diplomatic interests), and national security concerns (e.g., protecting Americans from external threats, promoting stability).44

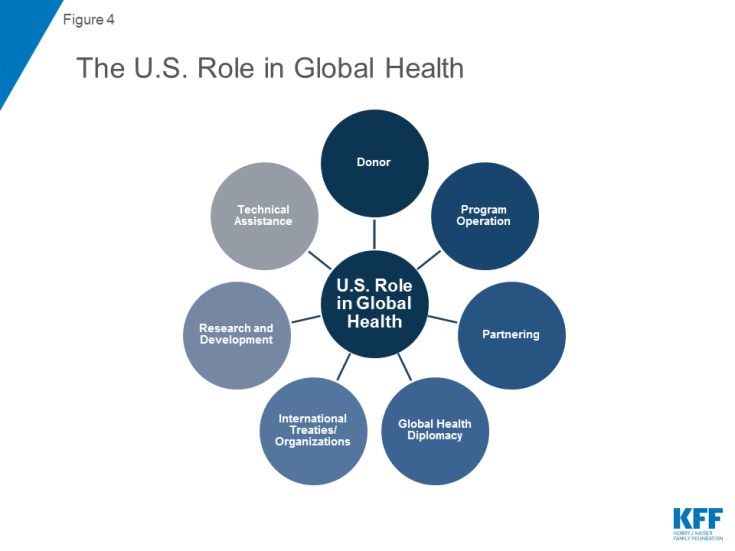

Components of the U.S. engagement on global health include policies (such as legislation, regulations, executive orders, guidance, and other relevant issuances that address global health) and a broad range of initiatives and programs that are meant to improve health in low- and middle-income countries. The U.S. role is multifaceted (Figure 4), and includes such activities as:

- Acting as a donor by providing financial and other health-related development assistance (e.g., commodities) to low- and middle-income countries, through both bilateral and multilateral channels;

- Engaging in global health diplomacy through international negotiations and agreements;

- Providing technical assistance and other capacity-building support to countries and organizations;

- Operating (i.e., implementing) programs and delivering health services in other countries;

- Participating in governance of and membership in major international health organizations such as WHO and the Global Fund;

- Engaging in global health research and development efforts;

- Partnering with governments, non-governmental groups, and the private sector; and

- Supporting international responses to disasters and other emergencies to save lives and livelihoods.

U.S activities are targeted at a broad range of issues, and use different intervention approaches such as:

- Health services and systems: Improving basic and essential health services, systems, and infrastructure;

- Disease detection and response: Supporting surveillance, prevention, and treatment of diseases including both infectious and non-communicable diseases;

- Population and maternal/child health: Promoting maternal health; reproductive health and family planning; child nutrition, immunization, and other child survival interventions;

- Nutrition, water, and environmental health: Providing non-emergency food aid, and supporting dietary supplementation, food security; clean/safe water and sanitation; mitigation of environmental hazards; and

- Research and development: Investigating and developing new technologies, interventions, and strategies including vaccines, medicines, and diagnostics.

These broad areas are often carried out as part of larger development assistance and poverty alleviation efforts, activities designed to enhance access to basic and higher education, and interventions that address gender inequalities and empower women and girls. In addition, the U.S. government has a long-standing engagement in providing humanitarian aid and disaster relief, including activities that are not directly focused on health but which can serve to mitigate or prevent adverse health outcomes.

Which Agencies and Programs of the U.S. Government Are Involved in Global Health?

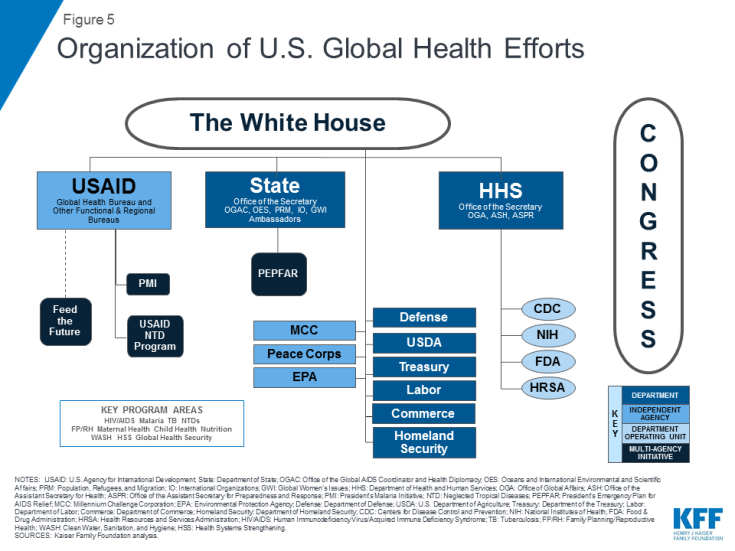

The U.S. government’s engagement in global health is overseen and carried out by multiple agencies and departments, and several congressional committees (see Figure 5). In general, U.S. global health engagement has developed within two main structures of the government: the foreign assistance structure, which is predominantly global development-oriented and has close links to foreign policy, and the public health structure, which has its roots in disease prevention, control, and surveillance efforts. Most funding for and oversight of U.S. global health resides within the foreign assistance structure, including at the Department of State (State), the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), and the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC). The public health structure, represented most prominently by several agencies within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), also plays an important global health role. Additional departments and agencies are also involved in global health, including the Department of Defense (DoD), the Department of Agriculture (USDA), the Peace Corps, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), the Department of Labor (DoL), the Department of Commerce (Commerce), the National Security Council (NSC), and the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR).

A schematic of the U.S. government’s global health organization can be seen in Figure 5 below.

Foreign Assistance Agencies

U.S. global health engagement is primarily based in foreign assistance agencies, which receive the bulk of government funding appropriated by Congress to operate the majority of global health programs and activities.

Department of State (State):

Established in 1789, the State Department is the Cabinet-level foreign affairs agency of the United States. The Department advances U.S. objectives and interests in the world through its primary role in developing and implementing the President’s foreign policy. The State Department also provides policy direction to USAID, the lead federal agency for development assistance. Most of the State Department’s global health policy development and coordination activity is overseen by the Under Secretary for Civilian Security, Democracy, and Human Rights, the Under Secretary for Economic Growth, Energy, and the Environment, and the Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator and Health Diplomacy (OGAC). Through OGAC (created in 2003), the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator oversees the implementation of the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), exercising oversight authority over all funding and activities for global HIV carried out by multiple departments and agencies. OGAC also provides diplomatic support (through U.S. Ambassadors and others) in implementing U.S. global health efforts.45 In addition, the State Department contributes to the development of the U.S. government’s Global Water Strategy, which addresses clean water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) efforts in developing countries, as charged by the Senator Paul Simon Water for the Poor Act of 2005 and Water for the World Act of 2014. More information on PEPFAR and U.S. WASH efforts can be found in the “What Are The Major U.S. Global Health Program Areas And Efforts?” section below.

U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID):

Established in 1961, USAID is an independent U.S. federal government agency that receives overall foreign policy guidance from the Secretary of State. USAID’s role is to support long-term and broad-based economic growth in countries and advance U.S. foreign policy objectives by supporting activities in each of its programmatic functional bureaus (e.g., Bureau for Global Health) as well as regional bureaus. Most USAID global health programs are coordinated through the Bureau for Global Health, including HIV/AIDS and other infectious diseases, maternal and child health, family planning and reproductive health, nutrition, and environmental health. Other bureaus and offices within USAID that address global health issues include the Bureau for Economic Growth, Education, and Environment, which implements clean water and sanitation projects, and the Bureau for Democracy, Conflict, and Humanitarian Assistance, which administers the largest U.S. international food assistance program, the Food for Peace Program (Public Law 480 Title II). USAID serves as the lead agency for the President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI), which is implemented with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and also serves as one of the main PEPFAR implementing agencies. More information on PMI, PEPFAR, and USAID programs can be found in the “What Are The Major U.S. Global Health Program Areas And Efforts?” section below.

Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC):

Established in 2004, MCC administers the Millennium Challenge Account (MCA), a U.S. government initiative which provides development assistance to eligible countries in order to promote economic growth and reduce poverty in low- and middle-income countries. MCC supports a number of health-related programs, but health is not the main focus or purpose of its work; it is designed to link contributions for development assistance to greater responsibility by developing nations. The MCC is a government corporation with a Board of Directors that includes the Secretary of State (Chair), the Secretary of Treasury, the U.S. Trade Representative, the Administrator of USAID, the CEO of the MCC, and four public members appointed by the U.S. President with the advice and consent of the U.S. Senate. For further details on these activities, see the KFF fact sheet on The Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) and Global Health.

Public Health Service Agencies

Public health service agencies operate global health programs directly, or in conjunction with foreign assistance agencies.

Department of Health and Human Services (HHS):

Established as a Cabinet-level department in 1953, HHS is the U.S. government’s principal agency for protecting the health of all Americans and providing essential human services. The Office of Global Affairs (OGA), which reports directly to the Secretary and is led by the Director of OGA, provides policy guidance to and coordinates with other Federal departments and agencies, international organizations, and the private sector on international and refugee health issues, and manages the health attaché program. While HHS directly operates some in-country programs, much of its global health efforts are provided through technical assistance to foreign assistance agencies through four HHS operating divisions:

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): With a long history working on international health issues, CDC focuses on disease control and prevention and health promotion through operations, development assistance, basic and field research, technical assistance, training/exchanges, and capacity building. A strategic framework adopted in 2007 explicitly includes global health promotion among CDC’s overarching goals, and in 2010, the agency created a new Center for Global Health (CGH) to lead the agency’s global health effort across its many different centers and offices and with partner countries. CGH consists of four divisions: the Division of Global HIV and TB, which works with Ministries of Health (MoH) to combat HIV/AIDS through PEPFAR; the Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria, which works with USAID to implement PMI; the Division of Global Health Protection, which houses the Field Epidemiology Training Program (FETP) and the Global Disease Detection Operations Center; and the Global Immunization Division, which provides support to MoHs to control vaccine-preventable diseases worldwide. Additionally, the CDC Office of Infectious Diseases (OID) includes three national centers and also works to coordinate global health activities.46

- National Institutes of Health (NIH): One of the world’s leading research entities on global health, NIH conducts biomedical and behavioral science research on diseases and disorders to enhance diagnosis, prevention, and treatment and provides technical assistance and training. All 27 of the agency’s institutes and centers engage in global health activities. In particular, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) carries out a significant amount of global health research on infectious diseases, including HIV, as well as on immunologic and allergic diseases and conditions. NIH also operates the Fogarty International Center, which works to build partnerships between health research institutions in the U.S. and abroad and train research scientists. NIH also serves as a PEPFAR implementing agency by supporting research on HIV infection, co-morbidities, and new therapies and vaccines.

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA): The FDA screens pharmaceutical and biological products for safety and efficacy, and helps oversee the safety of the U.S. food supply. As a PEPFAR implementing agency, FDA is charged with expediting the review of pharmaceuticals to ensure that OGAC can buy safe and effective antiretroviral drugs at the lowest possible prices. In recent years the FDA has made efforts to increase its overseas presence and coordination with partner governments to better promote its mission of protecting the health of U.S. citizens, especially through an emphasis on improving regulatory capacity abroad.47

- Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA): HRSA builds human and organizational capacity and promotes health systems strengthening to deliver care in PEPFAR countries.

Other Departments And Agencies Involved In Global Health

The remainder of U.S. global health activities is carried out by programs at several other federal departments and agencies. These include:

- Department of Defense (DoD): Supports a broad set of humanitarian assistance and disaster relief, military-to-military health systems capacity-building, care delivery, international training and exchanges, disease surveillance, and health research and product development activities. For further details on these activities, see the KFF report, “The U.S. Department of Defense and Global Health.”48

- Department of Agriculture (USDA): Provides food assistance (primarily commodities) to low-income countries.

- The Peace Corps: Provides volunteers to communities in developing nations in support of PEPFAR, maternal and child health, basic health services, and other health areas.

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA): Focuses on mitigating environmental hazards that represent inherently transnational threats, and building partnerships to enhance research, policy, and standards development capacity of developing nations.

- Department of Homeland Security (DHS): Lead agency on all matters of domestic security, facilitating communication among international and domestic partners during crises.

- Department of Labor (DoL): Focuses on promoting safe workplaces and preventing child labor and exploitation globally, including through HIV/AIDS workplace education programs.

- Department of Commerce (Commerce): Fosters public-private partnerships for HIV/AIDS as part of PEPFAR; compiles and manages country-level data on HIV.

- National Security Council (NSC): Located in the Executive Office of the President, serves as the principal forum for considering national security issues related to global health threats.

- Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR): Located in the Executive Office of the President, promotes, negotiates, and shapes U.S. interests in global free trade, including protection of intellectual property rights.

Congressional Committees with Jurisdiction Over U.S. Global Health Efforts

Congress drafts program specific legislation, recommends overall funding levels, specifies how funds should or should not be spent, and appropriates funds to U.S. global health programs. More than 15 congressional committees have some jurisdiction and oversight over global health. The major committees with jurisdiction are listed below.

Authorization and Oversight Committees

- House Committee on Foreign Affairs: Responsible for oversight and legislation relating to all foreign assistance, including programs operated by the State Department, the MCC, and USAID. Key subcommittee: Africa, Global Health, Global Human Rights, and International Organizations, which has jurisdiction over global health issues generally, including specific responsibility for the region of sub-Saharan Africa, as well as over issues relating to the United Nations and its agencies.

- Senate Committee on Foreign Relations: Responsible for oversight and legislation relating to all foreign assistance, including programs operated by the State Department, the MCC, and USAID. Key subcommittees include: Africa and Global Health Policy as well as Multilateral International Development, Multilateral Institutions, and International Economic, Energy, and Environmental Policy.

- House Committee on Energy and Commerce:Has jurisdiction over a number of areas of health care, including biomedical research, public health, and the regulation of drugs. Key subcommittees include: Health as well as Oversight and Investigations.

- Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions: Has jurisdiction over a number of areas of health care, including biomedical research, public health, and the regulation of drugs.

Appropriations Committees

- Senate and House Appropriations Committees. Key subcommittees in each Appropriations Committee are: State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs (with responsibility for the State Department and USAID) and Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies (with responsibility for NIH and CDC).

A more complete reference document listing congressional committees with jurisdiction over global health by department, agency, and initiative can be found in Appendix A.

Major Statutes Guiding U.S. Global Health Efforts

The U.S. global health response has been defined by numerous governing statutes, authorities, and policy decisions, with most legislative and policy activity occurring in the past 15 years. Two major acts have established the main agencies that carry out global health activities and specify where and how funds should be directed:

- The Public Health Service Act of 1944: Consolidated and revised all existing legislation relating to the Public Health Service (PHS, which had been created a few decades earlier), outlined the policy framework for federal-state cooperation in public health; and established regulatory authorities that transferred the PHS to the Department of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW), now known as the Department of Health and Human Services.

- The Foreign Assistance Act of 1961: Reorganized U.S. foreign assistance programs, including separating military and non-military aid, and mandated the creation of an agency to administer economic assistance programs, which led to the establishment of USAID. While amendments and other changes have been made to the Foreign Assistance Act over time, it has only been reauthorized once, in 1985.

In addition to the general foreign assistance statutes listed above, the legislation that created PEPFAR in 2003 and its re-authorizations in 2008, 2013, and 2018 are also key statutes for U.S. global health policy.

- PEPFAR legislation (originally authorized in 2003): Titled the United States Leadership Against HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria Act of 2003 (P.L. 108-25 or “Leadership Act”), the original PEPFAR authorization legislation created OGAC and authorized $15 billion over five years to combat global HIV/AIDS (as well as TB and malaria). In 2008, PEPFAR was reauthorized by the Tom Lantos and Henry J. Hyde United States Global Leadership Against HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria Reauthorization Act of 2008 (P.L. 110-293 or “Lantos-Hyde”), for an additional five years (FY 2009 – FY 2013) at up to $48 billion. In 2013, the PEPFAR Stewardship and Oversight Act of 2013 (P.L. 113-56 or “PEPFAR Stewardship Act”) extended a number of existing authorities for an additional five years (FY 2014 – FY 2018) and strengthened the oversight of the program through updated reporting requirements, among other things.49 Most recently in 2018, PEPFAR was reauthorized by the PEPFAR Extension Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-305) for an additional five years (FY 2019 – FY 2023). For further details on PEPFAR legislation, see the KFF issue brief “PEPFAR Reauthorization.”

Other Acts of Congress have also been significant for global health. A timeline of the statutes, authorities, and policies governing U.S. global health policy can be found in Appendix B.

What Are The Major U.S. Global Health Program Areas And Efforts?

While the U.S. government has been engaged in international health activities for more than a century, the provision of development assistance for health began primarily in the 1960s and 1970s, with support for maternal and child health and family planning efforts. Efforts have grown markedly since the early 2000s, and have largely focused on disease-specific initiatives, including PEPFAR and the PMI.

Each of these programs works in a particular set of countries and typically has its own dedicated budget, staff, objectives, and monitoring and evaluation practices, and historically, these programs have not been well coordinated. The current Administration views global health as a key component of national security and aims to build upon and consolidate the successes of existing U.S. global health programs and initiatives (such as U.S. global HIV/AIDS efforts). It encourages countries to invest in their own basic health care systems by emphasizing “self-reliance” while working with countries to develop their capabilities, including preparedness and response capacities.50

This section gives an overview of the key U.S. global health programs that address the major global health challenges identified earlier.

HIV/AIDS/ PEPFAR51

The U.S. first provided funding to address the global HIV epidemic in 1986, although funding and attention did not increase significantly until the last 15 years. In 1999, President Clinton announced the Leadership and Investment in Fighting an Epidemic (LIFE) Initiative, and in 2002, President Bush announced the International Mother and Child HIV Prevention Initiative. A major increase in support for global HIV/AIDS programs occurred when President Bush announced the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) in 2003, which has been the largest commitment by any nation to combat a single disease in history.52,53 Its first five-year authorization through the United States Leadership Against HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria Act of 2003 (P.L. 108-25 or “Leadership Act”) was for $15 billion (Congress appropriated more over this period). PEPFAR was reauthorized by the Tom Lantos and Henry J. Hyde United States Global Leadership Against HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis, And Malaria Reauthorization Act of 2008 (P.L. 110-293 or “Lantos-Hyde”) for an additional five years starting in 2008, expanding goals for HIV, TB, and malaria efforts. In 2013, the PEPFAR Stewardship and Oversight Act of 2013 (P.L. 113-56 or “PEPFAR Stewardship Act”) extended a number of existing authorities for an additional five years starting in 2014 and strengthened the oversight of the program through updated reporting requirements, among other things.54 Most recently in 2018, PEPFAR was reauthorized by the PEPFAR Extension Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-305) for an additional five years (FY 2019 – FY 2023).55

PEPFAR is an interagency initiative that supports a range of HIV prevention, treatment, and care efforts worldwide, including prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV and the provision of antiretroviral drugs to millions. In 2011, Secretary of State Clinton called for an “AIDS-free generation” as a goal of the U.S. government, and in 2012, PEPFAR released a blueprint for achieving this goal.56,57 In 2014, PEPFAR 3.0 – Controlling the Epidemic: Delivering on the Promise of an AIDS-free Generation was released, reflecting a shift in its approach to controlling the epidemic, including targeting resources to key populations, especially adolescent girls and young women, and geographic areas that are most affected by HIV.58 PEPFAR’s current strategy aligns with the UNAIDS 90-90-90 framework, and emphasizes accelerating testing and treatment strategies, expanding prevention, using data to increase PEPFAR’s impact and effectiveness, engaging with faith-based organizations and the private sector, and strengthening policy and financial contributions by partner countries.59

PEPFAR’s original authorization established an Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator at the Department of State, headed by a coordinator who is appointed by the President and requires Senate confirmation. The U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator has the rank of Ambassador and reports directly to the Secretary of State. The coordinator is responsible for all programs, activities, and funding for global HIV/AIDS efforts. Along with OGAC, the White House and the National Security Council (NSC) are involved in policy development for PEPFAR. USAID and CDC are the main PEPFAR implementing agencies and receive direct funding from Congress. Other implementing agencies include: NIH, HRSA, and FDA at HHS; DoL; Commerce; the Peace Corps; and DoD. For further information on U.S. global HIV efforts and PEPFAR, please see the KFF fact sheets on the Global HIV/AIDS Epidemic and the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief.

Tuberculosis60,61

USAID is the lead U.S. government agency on global tuberculosis control and began its efforts in 1998. The U.S. response to TB grew over time, and in 2003, the passage of the Leadership Act highlighted the U.S. commitment to addressing TB and authorized U.S. contributions to the Global Fund, significantly increasing the amount of support for TB programs by the U.S. government. PEPFAR’s reauthorization by the Lantos-Hyde Act in 2008 established specific funding levels and targets for TB. In 2015, the USG released its five-year USG TB Strategy 2015-2019, which outlines current USG TB goals. The same year, the USG also released its National Action Plan for Combating Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis, which identifies interventions and articulates a strategy to respond to the domestic and global challenges of MDR-TB.62 Most recently, at the U.N. High-Level Meeting on TB in 2018, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) released the Strategic Plan for Tuberculosis Research, which aims to accelerate its TB research including MDR-TB research.63 USAID’s TB efforts are focused on the diagnosis, treatment, and control of TB and multi-drug and extensively drug resistant (MDR/XDR) TB. Countries are selected to receive bilateral support for TB based on the prevalence and incidence of TB, HIV/AIDS prevalence, prevalence and/or potential for drug resistance, and case detection and treatment success rates. Political commitment and technical and managerial feasibility are also considered in country selections. For further information on U.S. global TB efforts, please see the KFF fact sheet on the U.S. Government and Global Tuberculosis Efforts.

Malaria/ PMI64,65

The U.S. has been involved in efforts to combat malaria since the 1950s through activities at CDC and USAID. Early efforts focused on technical assistance, but also included some direct financial support for programs overseas. U.S. efforts expanded over time, and the 2003 passage of the Leadership Act highlighted the U.S. commitment to addressing malaria and authorized multilateral support to combat the disease through contributions to the Global Fund. In 2005, President Bush announced the U.S. President’s Malaria Initiative, 66 initially a five-year expansion of existing U.S. government efforts to address malaria in certain highly-affected countries. In 2015, the U.S. released the President’s Malaria Initiative Strategy 2015-2020, which outlines its goals as well as its approach to achieving them by 2020.67 The PMI is an interagency initiative led by USAID, and implemented in partnership with CDC. It is overseen by the U.S. Global Malaria Coordinator, who is appointed by the President, and an Interagency Advisory Group made up of representatives of USAID, CDC, State, DoD, NSC, and the Office of Management and Budget. The coordinator reports to the USAID Administrator, and has direct authority over both the PMI efforts and non-PMI USAID malaria programs. U.S. efforts to control malaria include the distribution of insecticide-treated bed nets (ITNs), indoor residual spraying (IRS), intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy (IPTp), diagnosis of malaria and treatment with artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs), entomological monitoring, and seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC). For further information on U.S. global malaria efforts, please see the KFF fact sheet on the President’s Malaria Initiative and Other U.S. Government Global Malaria Efforts.

Neglected Tropical Diseases 68,69

Historically, the U.S. government had supported the NTD response through research and surveillance. In 2006, U.S. attention to NTDs increased when Congress first appropriated funds to USAID for integrated NTD control, marking the launch of the USAID NTD program. In 2008, the program was expanded under President Bush’s U.S. NTD Initiative. The USAID NTD program seeks to control seven NTDs in target countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America through mass drug administration programs. USAID serves as the lead implementing agency for U.S. global NTD efforts, with several other agencies, including CDC, NIH, DoD, and the FDA, also involved. For further information on U.S. global NTDs efforts, please see the KFF fact sheet on the U.S. Government and Global Neglected Tropical Disease Efforts.

Family Planning & Reproductive Health70,71

Research on international FP and population issues was first authorized by Congress in the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961. In 1965, USAID launched its first FP program and, in 1968, began purchasing contraceptives to distribute in developing countries. USAID serves as the lead agency on FP/RH. Its efforts aim to reduce high-risk pregnancies; allow sufficient time between pregnancies; provide information, counseling, and access to condoms to prevent HIV transmission; reduce the number of abortions; support women’s rights; and stabilize population growth. Funding is allocated to countries based on factors that include unmet need for family planning services, high-risk births, contraceptive use, and population pressures on land and water resources. For further information on U.S. international family planning and reproductive health efforts, please see the KFF fact sheet on the U.S. Government and International Family Planning & Reproductive Health Efforts.

Maternal and Child Health72,73

The U.S. government has been involved in efforts to improve MCH since the 1960s, initially focused on pioneering research on oral rehydration therapy (ORT). Other early programs included fortifying international food aid with vitamin A, and efforts to control malaria (because the bulk of malaria illness and death occurs in children). Funding for USAID’s child survival activities nearly doubled in 1985, and in 2001, USAID introduced a newborn survival strategy. In 2012, USAID, along with many other partners, held a child survival summit to re-energize support for child survival programs.74 USAID’s MCH strategy focuses on bringing a range of “high impact interventions” to scale, and on health systems strengthening (e.g., health workforce, pharmaceutical management, etc.). Funding is allocated to countries based on factors that include high maternal and child mortality burdens, government willingness to partner, and country capacity to implement programs. For further information on U.S. global maternal and child health efforts, please see the KFF fact sheet on the U.S. Government and Global Maternal & Child Health Efforts.

Nutrition/ Feed the Future (FtF) Initiative75,76

USAID has been involved in efforts to improve nutrition for more than 40 years. USAID’s nutrition program aims to prevent undernutrition through interventions such as nutrition education, nutrition during pregnancy, promotion of exclusive breastfeeding, and micronutrient supplementation. In 2014, USAID released, for the first time, a multisectoral nutrition strategy that focuses on improving linkages among its humanitarian, global health, and development efforts to better address both the direct and underlying causes of malnutrition and to build resilience and food security in vulnerable communities.77 Nutrition efforts are coordinated with the U.S. Feed the Future (FtF) Initiative. Introduced in 2009 following the

G-8 Summit in L’Aquila, Italy, FtF is the U.S. government’s global hunger and food security initiative. The initiative, led by USAID and USDA, works to reduce hunger, increase food security, and improve nutrition by investing in agricultural development and nutrition efforts, with an emphasis on country ownership, improving coordination, leveraging multilateral institutions, and ensuring long-term accountability, while addressing the underlying causes of hunger and poverty. FtF works closely with U.S. global health efforts to achieve nutrition targets. For further information on U.S. global nutrition efforts, please see the KFF fact sheet on the U.S. Government and Global Maternal & Child Health Efforts (which includes U.S. MCH and nutrition efforts).

Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene78,79

USAID’s water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) activities aim to build capacity, strengthen water and sanitation utilities, mobilize domestic resources, improve household and community-level hygiene and sanitation, and work with disaster relief efforts to implement water and sanitation activities. U.S. government efforts to address WASH issues are guided by the Senator Paul Simon Water for the Poor Act of 2005 (P.L. 109-121) and the Senator Paul Simon Water for the World Act of 2014 (P.L. 113-289), which requires the State Department, USAID (the main implementing agency), and other U.S. government agencies to develop and implement a U.S. government Global Water Strategy to provide “first-time or improved access to safe drinking water, sanitation, and hygiene to the world’s poorest on an equitable and sustainable basis” and to identify priority water countries for U.S. WASH efforts.80 These efforts provide assistance to developing countries through capacity building activities and partnerships as well as direct investment in WASH infrastructure and science and technology. USAID’s WASH efforts, which are led by the USAID Global Water Coordinator, focus on providing clean water and ensuring water security through U.S. global health and food security efforts, while the State Department’s efforts, which are led by the State Department’s Special Advisor for Water Resources, focus on diplomatic efforts related to WASH issues and water resources.81

Non-Communicable Diseases

With the growing recognition that the burden from non-communicable diseases (NCDs) is growing in low- and middle-income countries, attention to NCDs in the context of U.S. government programs has increased. For example, the U.S. played an important role in organizing the 2011 U.N. high level meeting on NCDs, and participated in negotiations on global NCD targets and the development of best practices to combat NCDs.82 Funding for NCD programs, though, remains only a small proportion of overall U.S. government global health spending. For further information on U.S. global NCD efforts, please see the KFF fact sheet on the U.S. Government and Global Non-Communicable Disease Efforts.

Global Health Security

Since the 1990s there has been growing concern about new and re-emerging infectious diseases that threaten human health. In the last several years alone we have seen the emergence and spread of threats such as Ebola, Zika, H1N1 influenza, and antibiotic resistance. Global health security efforts are meant to reduce the threat of such diseases by supporting preparedness, detection, and response capabilities worldwide. The U.S. has supported a number of global health security programs through agencies such as CDC, USAID, DoD, and the State Department.83 The U.S. has also played a key role in development of the “Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA),” an international partnership launched in 2014 and now involving more than 60 countries and international organizations. Through the GHSA, U.S. government agencies work with host governments and partners to help countries make measurable improvements in capabilities to detect and respond to emerging disease events and achieve global health security targets. For further information on U.S. global health security efforts, please see the KFF brief on the U.S. Government and Global Health Security.

In Which Countries Does The U.S. Support Global Health Programs?84

Decisions on where the U.S. focuses its global health programs are based on a number of factors. The burden of disease faced by countries is an important factor in determining support, with more support generally directed to countries facing a higher burden of disease. For example, PEPFAR and PMI funds have been directed principally at those countries with some of the highest burdens of HIV/AIDS and malaria, respectively. Still, other factors also influence where the U.S. directs its health assistance, including the presence of willing and able recipient partner governments, a history of positive relations and goodwill between the countries, strategic and national security priorities, funding, and personnel availability.

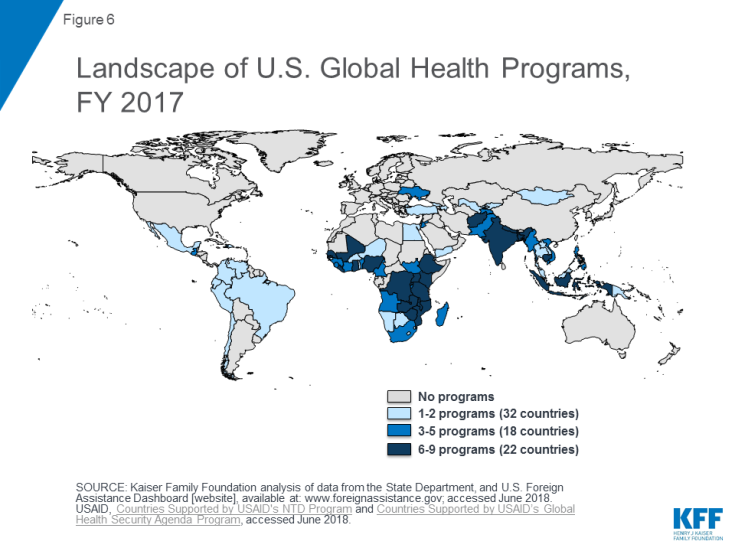

The U.S. operates programs in more than 70 countries, with other countries reached through regional programs and contributions to multilateral organizations. The majority of countries receiving U.S. bilateral support for global health are located in Africa (35 countries). The U.S. also operates programs in East Asia and Pacific (11 countries), the Western Hemisphere (10 countries), South and Central Asia (8 countries), the Near East (4 countries), and Europe and Eurasia (4 country).85 The U.S. often operates programs in a number of different areas (HIV/AIDS, TB, NTDs, etc.) in a given country (see Figure 6 and Table 1). For more detailed information on the countries where U.S. global health programs are present, please see Appendix C.

| Table 1: Number of Countries by Program Area and Region, FY 2017 | ||||||||||

| Region | HIV/AIDS | Tuberculosis | Malaria | Neglected Tropical Diseases | Maternal and Child Health | Family Planning and Reproductive Health | Nutrition | Water Supply and Sanitation | Global Health Security | Other Public Health Threats |

| Africa | 27 | 11 | 25 | 17 | 20 | 21 | 13 | 16 | 12 | 0 |

| East Asia and Pacific | 5 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 0 |

| Europe and Eurasia | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Near East | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| South and Central Asia | 3 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 1 |

| Western Hemisphere | 3 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Total | 39 | 22 | 27 | 31 | 35 | 32 | 21 | 29 | 29 | 2 |

| Source: KFF analysis of data from the State Department, Foreign Assistance Dashboard [website], available at: http://www.foreignassistance.gov; accessed June 2018. USAID, Countries Supported by USAID’s NTD Program, available at: https://www.neglecteddiseases.gov/where-we-work accessed June 2018. USAID, Countries Supported by USAID’s Global Health Security Agenda Program, available at: https://www.usaid.gov/what-we-do/global-health/health-systems/countries accessed June 2018. | ||||||||||

What Is the U.S. Global Health Budget?

The U.S. government is the largest donor to global health in the world.86 U.S. government funding for global health has grown significantly since 2000, in large part due to funding for initiatives such as PEPFAR and PMI. More recently, however, U.S. funding for global health has begun to flatten. Most U.S. funding for global health is provided bilaterally, with the majority of multilateral funding provided to the Global Fund.

The majority of U.S. government funding for global health is captured under the Global Health Programs (GHP) account at USAID and the State Department. Additional funding for global health is provided through the Economic Support Fund (ESF) and Development Assistance (DA) accounts at USAID, the International Organizations and Programs (IO&P) and the Contributions to International Organizations (CIO) accounts at the State Department, and through CDC, NIH, and DoD.87

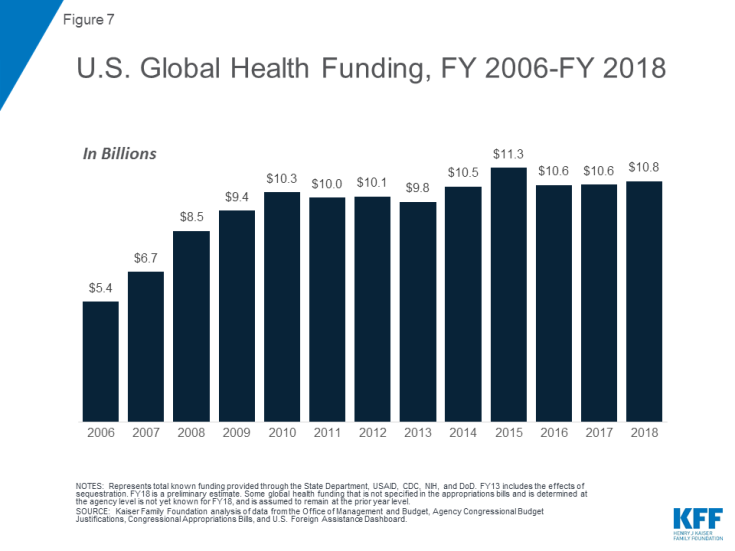

Specified funding for global health grew from $5.4 billion in FY 2006 to $10.3 billion in FY 2010 and has since remained relatively flat, totaling an estimated $10.8 billion in FY 2018 (see Figure 7).88 For further information on U.S. global health funding by program area, see the KFF fact sheet on Breaking Down the U.S. Global Health Budget by Program Area.

Bilateral vs Multilateral Aid

Most U.S. global health funding is provided bilaterally. In FY 2018, 81% of the U.S. global health budget was provided through bilateral programs. U.S. contributions to multilateral institutions account for the other 19%, the majority of which is provided to the Global Fund.89

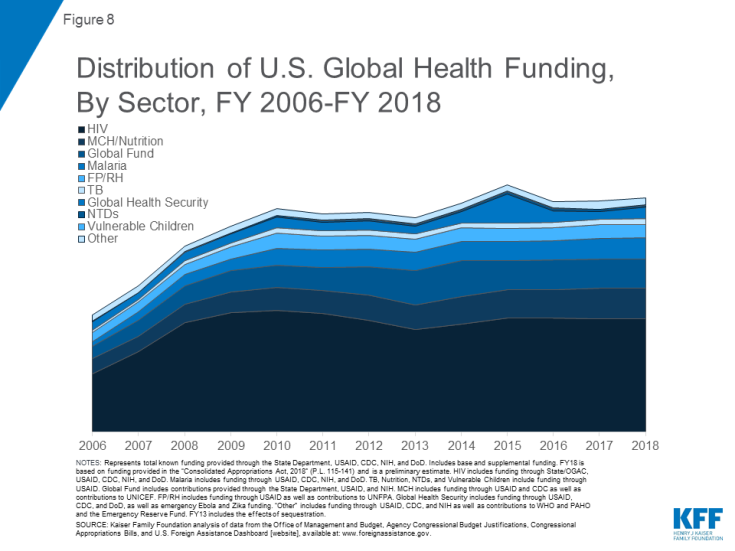

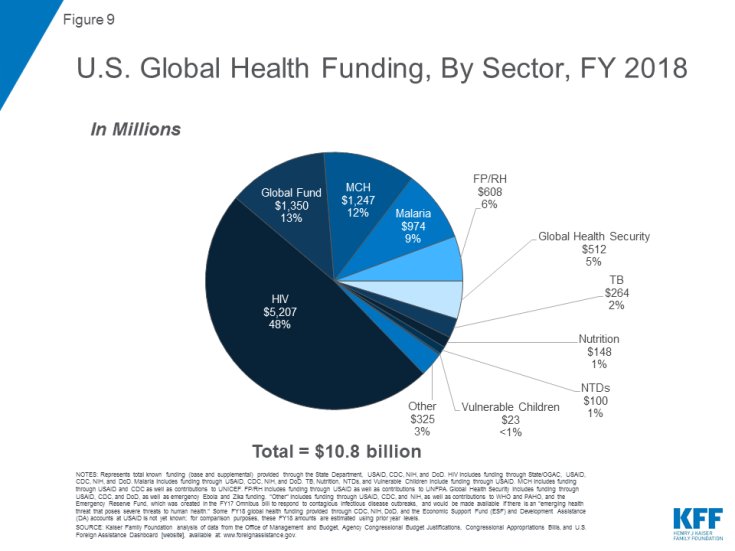

U.S. Global Health Funding By Sector

Bilateral HIV programs have received the most U.S. global health funding of any sector, accounting for approximately 50% of U.S. global health funding from FY 2006 through FY 2018 (see Figure 8). The Global Fund accounted for the next largest share over the period, followed by MCH (including nutrition) and malaria.90 The largest share of global health funding in FY 2018 is for bilateral HIV ($5.2 billion), followed by the Global Fund ($1.35 billion), MCH ($1.2 billion), malaria ($974 million), FP/RH ($608 million), Global Health Security ($512 million), TB ($264 million), nutrition ($148 million), NTDs ($100 million), and vulnerable children ($23 million).91 An additional $325 million is provided for other global health activities, which include contributions to WHO, the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), research activities at the Fogarty International Center, and the Emergency Reserve Fund, which was created in the FY 2017 Omnibus bill to respond to contagious infectious disease outbreaks (see Figure 9).

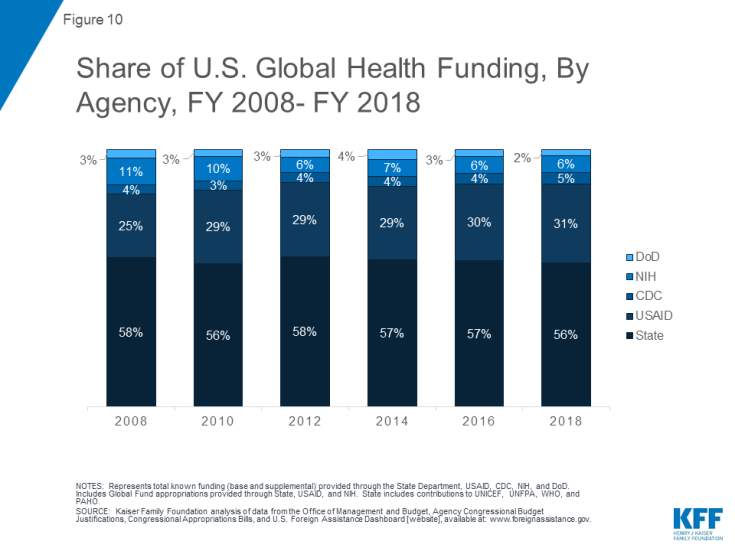

U.S. Global Health Funding By Agency

Most U.S. global health funding is provided under the international affairs budget, which includes funding for USAID and the State Department. The State Department receives the majority of funding, largely due to the fact that most of PEPFAR’s funding is channeled through the State Department (see Figure 10). Prior to the creation of PEPFAR, the majority of U.S. global health funding was provided through USAID. In FY 2018, the State Department received $6.0 billion, followed by USAID ($3.3 billion), HHS ($1.2 billion), and DoD ($246 million).

U.S. Global Health Funding By Region And Country

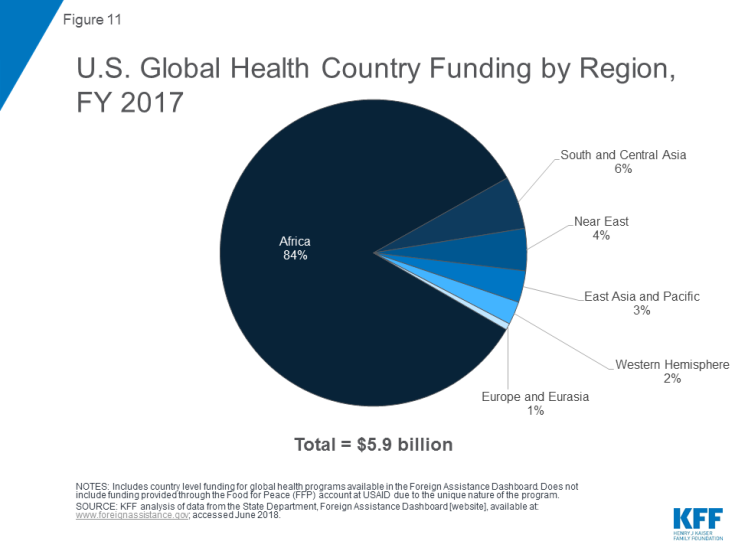

More than 80% of country funding is allocated for global health activities in Africa (see Figure 11), followed by South and Central Asia (6%), the Near East (4%), East Asia and Pacific (3%), the Western Hemisphere (2%), and Europe and Eurasia (1%). Nine of the top ten recipient countries of U.S. global health funding in FY 2017 were in Africa (see Figure 12). The top three recipients were: Kenya, Tanzania, and South Africa. African countries comprised the top 10 most heavily funded recipient countries for malaria and HIV/AIDS, six of 10 for FP/RH, seven of 10 for MCH, and seven of 10 for nutrition. Countries in South and Central Asia also received significant amounts of funding in multiple areas, particularly TB.

How Does The U.S. Engage With Multilateral Organizations On Global Health?

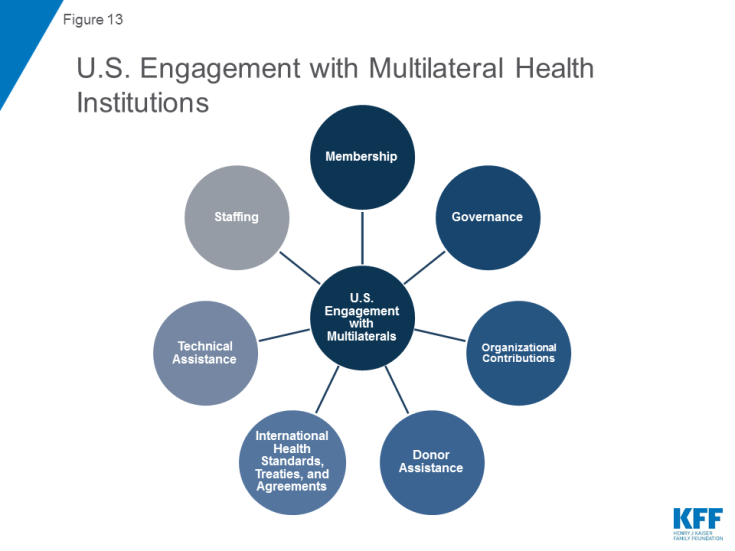

In addition to its own bilateral programs, the U.S. government has a long history of involvement with international health organizations, beginning with its role in the development of the first such organizations, including PAHO in the early 1900s and WHO a few decades later, and continuing through to the present with the Global Fund, which the U.S. helped to launch in 2001. Approximately 19% of U.S. global health funding was allocated to multilateral organizations in FY2018, including $1.35 billion for the Global Fund alone. Still, funding is only one of the ways the U.S. supports and engages with multilateral organizations (Figure 13). Some of the other ways include:

- Membership: The U.S. is a member nation of the large multilateral health organizations, including WHO, PAHO, and the Global Fund.

- Governance: The U.S. sits on the Board or main organizing body of several of the major multilateral health organizations, such as the Global Fund, WHO, and UNAIDS, providing it with decision-making authority and other governance roles.

- Organizational Contributions: The U.S. provides funding to multilateral health organizations for their operations and other activities through scheduled assessments and often through additional, project or program-specific support.

- International Health Standards, Treaties, and Agreements: The need to set international standards for preventing the spread of infectious diseases at ports and borders without unduly restricting trade and travel fostered the creation of the earliest international health organizations in the nineteenth century; those efforts served as precursors to the development of the International Health Regulations (IHR) of today. The IHR are an international legal instrument that entered into force in 2007, requiring countries to report certain disease outbreaks and public health events to WHO. Other examples of significant international health agreements include the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the U.N. Declaration of Commitment on HIV/AIDS, and the WHO International Framework Convention for Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC).

- Technical Assistance: The U.S. provides technical assistance to international organizations directly and indirectly, such as by providing assistance to Global Fund country applicants in preparing proposals for funding and providing U.S. government scientists to serve as experts on WHO technical committees.

- Staffing: The U.S. provides additional staff capacity to international organizations by detailing government employees for varying periods of time.

Main Multilateral Health Organizations With U.S. Involvement

- The World Health Organization (WHO): The WHO, created in 1948, is the directing and coordinating authority for health within the United Nations system. The U.S. was a founding member, joining in that year. WHO provides international leadership on global health matters, shaping the health research agenda, setting norms and standards (such as the IHR), providing technical support to countries, and monitoring and assessing health trends. It is governed by the World Health Assembly (attended by all Member states) and an Executive Board of 34 members, of which the U.S. is currently a member through 2021.92 For further information on U.S. engagement with WHO, please see the KFF fact sheet on the U.S. Government and the World Health Organization.

- The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO): PAHO is the oldest international health agency, founded originally as the International Sanitary Bureau in 1902. The U.S. joined PAHO as a member state in 1925. PAHO “works to improve health and living standards of the people of the Americas” and serves as the WHO Regional Office for the Americas and as the health organization of the inter-American System.

- The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (Global Fund): Created in 2001, the Global Fund is an independent, public-private, multilateral institution that finances HIV, TB, and malaria programs in low- and middle-income countries. The U.S. government was involved in the creation of the Global Fund and maintains a permanent seat on its Board.93 It is also the largest single donor to the Global Fund in the world. Contributions provided by the U.S. and other donors are in turn provided by the Fund to country-driven projects based on technical merit and need. For further information on U.S. support for the Global Fund, please see the KFF fact sheet on the U.S. & The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria.

- The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS): UNAIDS, created in 1996 as the successor organization to the WHO Global Programme on AIDS (GPA), is the leading global organization for addressing HIV/AIDS, coordinating efforts across the United Nations system. It is made up of 11 U.N. co-sponsors and guided by a Programme Coordinating Board (PCB), which is a subset of its co-sponsors and government representatives. The U.S. currently serves on the PCB.

- Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance (Gavi): Gavi is a public-private partnership created in 2000 to “save children’s lives and protect people’s health by increasing access to immunizations in poor countries.”94 For further information on U.S. engagement with Gavi, please see the KFF fact sheet on the U.S. & Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance.

The U.S. also often contributes to several other multilateral organizations including the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the World Food Programme (WFP), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA).95 The current Administration, however, has proposed pulling back engagement with some multilateral organizations, creating questions about future U.S. support.96 Lastly, the U.S. government also provides contributions to some of the world’s Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs, such as the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank), autonomous international agencies that finance development programs, including health programs, in low- and middle-income countries using borrowed money or funds contributed by donor countries.

Conclusion

U.S. engagement in global health spans many decades and has increased over time. Today, the U.S. global health architecture includes multiple agencies and programs and hundreds of international and local partners, and reaches most low- and middle-income countries around the world. The U.S. is also the largest funder of the global health response. Given its reach and funding, its future trajectory in this area will have a major impact on the world’s response to ongoing and new global health challenges.

Appendices

Appendix A: Congressional Committees Jurisdiction Over U.S. Global Health Activities

| Departments/Agencies | House | Senate |

| Department of State (State)

United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) |

|

|

Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)

|

|

|

| Department of Defense (DoD) |

|

|

| Department of Agriculture (USDA) |

|

|

| Peace Corps |

|

|

| Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) |

|

|

| Department of Homeland Security (DHS) |

|

|

| Department of Labor (DoL) |

|

|

| Department of Commerce (Commerce) |

|

|

| Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) |

|

|

| + All Subcommittees listed are part of House and Senate Standing Appropriations Committees | ||

Appendix B: Timeline of Governing Statutes, Authorities, Policies, and Initiatives for U.S. Global Health

| Year | Agency | Title | Purpose |

| 1798 | HHS | Act for the Relief of Sick and Disabled Merchant Seamen | Created the Marine Hospital Service, a federal network of hospitals for the care of merchant seamen. Renamed the “Public Health and Marine-Hospital Service” in 1902 and the Public Health Service in 1912.1 |

| 1930 | USDA | Foreign Agricultural Service Act of 1930 (P.L. 71-304) | Created the Foreign Agricultural Service (FAS) which today is part of the USDA. Among its responsibilities is the provision of food aid and technical assistance.2 |

| 1944 | HHS | Public Health Service Act (Title 42, U.S. Code) | The Public Health Service Act of July 1, 1944 (42 U.S.C. 201) consolidated and revised all existing legislation relating to the Public Health Service, outlined the policy framework for Federal-state cooperation in public health; and established regulatory authorities that transferred with PHS to the Department of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW) and subsequently to the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The scope of the Act has been significantly broadened over time. The full act is captured under Title 42 of the US Code, “The Public Health and Welfare.”3 |

| 1954 | USDA USAID |

Public Law 83-480. The Agricultural Trade Development Assistance Act of 1954, renamed The Food for Peace Act in 1961 | Authorized concessional sales of U.S. agricultural commodities to developing countries and private entities by USDA (Title 1); direct donation of U.S. agricultural commodities for emergency relief and development (Title II) and government-to-government grants of agricultural commodities tied to policy reform (Title 3), both assigned to USAID in 1961 (also known as P.L. 480).4,5 |

| 1960 | HHS | International Health Research Act of 1960 (Public Law 86-610) | To advance the health sciences through cooperative international research and training. Established the National Institute for International Health and Medical Research, to provide for international cooperation in health research, research training, and research planning, and for other purposes. Section 307 as amended (incorporated into USC Title 42) authorized the Secretary of HHS to enter into international cooperative agreements for biomedical and health activities.6 |

| 1961 | USAID, State | Public Law 87-195. The Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (FAA) | Reorganized U.S. foreign assistance programs including separating military and non-military aid and mandated the creation of an agency to administer economic assistance programs, which led to the establishment of USAID. Act created a policy framework for foreign assistance to developing nations and mandated the creation of an agency to promote long-term assistance for economic and social development.7,8 |

| 1973 | USAID, State | Public Law 93-189. The New Directions Legislation of 1973 (in the Foreign Assistance Act of 1973) | Amended the FAA of 1961, directing USAID to focus its operational programs on five categories of assistance for meeting the basic needs of the poorest countries in the following areas: food and nutrition; population planning; health, education, and human resources development; selected development problems; selected countries and organizations.9 |

| 1984 | USAID,

State |

“Mexico City” Policy | President Reagan directive expanded prohibition on use of federal funds by foreign NGOs beyond existing requirements in the FAA of 1961, other law, and policies to also prohibit NGOs from using any funds, including non-federal funds, to “perform or actively promote abortion as a method of family planning” as a condition for receiving U.S. global family planning assistance. Rescinded in 1993 by President Clinton. Reinstated in 2001 by President Bush and extended to apply to “voluntary population planning” assistance provided by the Department of State. Rescinded by President Obama in 2009. Reinstated, and expanded to the vast majority of U.S. global health assistance, in 2017 by President Trump.10 |

| 1985 | USDA | The Food for Progress Act of 1985 (Public Law 99-198 (Title XI) | Authorized USDA to provide U.S. agricultural commodities to emerging democracies and developing countries committed to promoting free enterprise in agricultural development.11 |

| 1985 | DoD | Public Law 99-661 (Section 333) Humanitarian and Civic Assistance (HCA) program in the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1987, as amended in: Title 10 USC §401, §402 | Authorized U.S. military forces to carry out humanitarian and civic assistance activities in conjunction with other operations (such as joint exercises) if such activities support mutual U.S.-host country interests, build U.S. force operational readiness skills, and do not duplicate other USG assistance (401); permits the military to transport humanitarian supplies for NGOs without charge (“the Denton Amendment,” Section 402).12,13 |

| 1996 | Govt-wide; main roles for State, USAID, DoD, CDC, NIH | Presidential Decision Directive NSTC-7 on Emerging Infectious Diseases | White House established national policy to address emerging infectious disease threats through improved domestic and international surveillance, prevention, and response measures, as follow-up to National Science and Technology Council (NSTC) reports: “Infectious Disease – A Global Health Threat” (September 1995), “Meeting the Challenge — A Research Agenda for Health, Safety, and Food” (February 1996), and “Proceedings of the Conference on Human Health and Global Climate Change” (May 1996). Directive establishes standing NSTC Task Force on emerging infectious diseases.14 |

| 1999 | USAID, DoD, CDC | Leadership and Investment in Fighting an Epidemic (LIFE) Initiative | New program announced by President targeting funding for HIV to 14 hard hit countries in Africa and to India.15 |

| 1999 | DoD | Executive Order 13139 | Established the HIV and AIDS Research and Development Program within the Department of the Army.16 |

| 2000 | CDC | Public Law 106-113. Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2000, as described in House Report 106-419 | Congress first appropriated funding specifically for CDC’s international AIDS activities ($35 million), used to support the newly launched CDC Global AIDS Program (GAP).17 |