A Check Up on U.S. Global Health Policy, After One Year of the Trump Administration

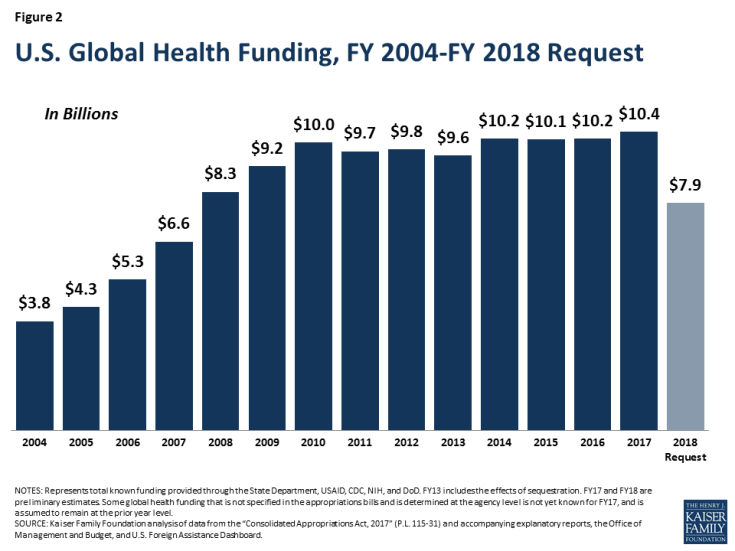

This month marks one year since Donald Trump became the 45th President of the United States after winning the election on a populist, “America-First”, platform. Since then, there have been many questions raised about what a Trump Presidency would mean for U.S. global health policy in light of statements on scaling back foreign aid and a skepticism of the value of multilateral institutions and key international agreements. Historically, global health has enjoyed bipartisan support and been highlighted as a major area of success for the United States. Funding for global health rose significantly in the last decade and, although it has leveled off, it still represents the largest component of U.S. foreign assistance (an estimated 24% in FY 2017).

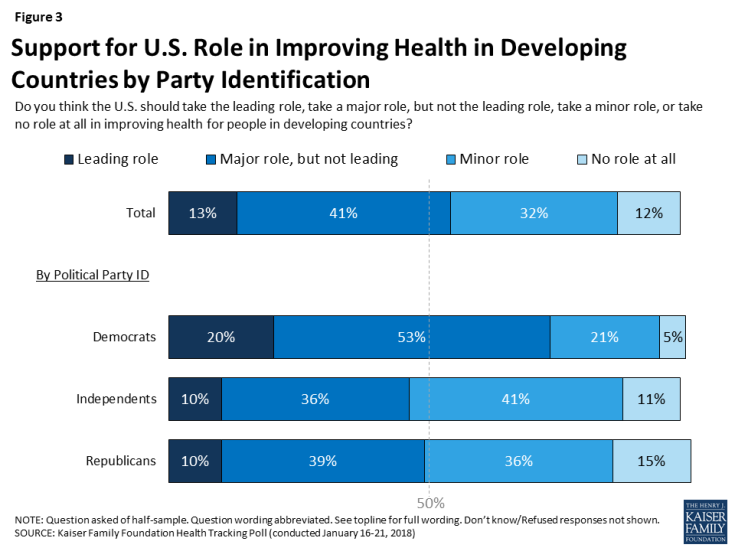

In this brief, we take stock of the U.S. global health response on the occasion of one year of the Trump Presidency and look ahead to the global health policy issues that are likely to be front and center in the coming months and years. Overall, there are a mix of challenges facing the U.S. global health response, some of which pre-dated Trump and others that are the result of decisions and actions of the administration, including proposals to significantly scale back funding. At the same time, global health programs still enjoy strong bipartisan support in Congress and, according to our just-released poll, about half of the public still wants the U.S. to play a major or leading role in improving health in developing countries (see Figure 1 and Appendix).

Figure 1: Half of the Public Sees Leading or Major Role for the U.S. in Improving Health in Developing Countries

DIAGNOSIS

Administration Actions Have Led to Foreign Policy Upheaval

In keeping with the “America First” campaign and promises to re-examine the U.S. role in world affairs, the Trump Administration has made a number of notable changes in broader U.S. foreign policy that affect global health. These include the administration’s decision to withdraw from the Paris Climate Accord, its criticism of and new demands for U.S. engagement in the context of international trade agreements such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and skepticism of, and intent to reduce U.S. support for the United Nations and potentially other multilateral organizations. More recently, the administration has proposed to cut foreign aid to countries that voted counter to U.S. government wishes at the UN. While this threat is not without precedent, it is a departure from U.S. policy over the prior two decades, and underscores the administration’s theme of emphasizing U.S. interests over other considerations.

The Trump Administration has also sought to make its mark on the agencies that carry out U.S. foreign policy, including the State Department and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). Following a March 2017 White House Executive Order on reorganizing the executive branch, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson has attempted to re-organize and reform these agencies. One potential move that was feared by many was the idea of “merging” USAID and the State Department – the two currently exist as quasi-independent – but to date there is no evidence of such a change being actively pursued. At the same time, budget requests from the White House have demonstrated the administration’s desire to make significant cuts to these agencies’ budgets, and their day-to-day management has been criticized by current and former employees. In addition, there has been decidedly slow progress in nominating and appointing staff for key foreign policy leadership posts, along with a notable exodus of experienced staff over the last year. For example, as of this writing, President Trump had nominated far fewer candidates at the State Department (89) compared to Presidents Obama (137) and George W Bush (153) at the same point in their first terms.

And, whereas human rights has been a component of U.S. foreign policy that the Obama Administration sought to elevate in its foreign policy (even including it prominently in its national security strategy), Trump Administration officials have downplayed the importance of human rights, leading to worries in the foreign policy and development community, and letters of concern from members of Congress.

Implications for Global Health

A lack of ambassadors in some countries, needed staff appointments in some positions, a shifting stance on human rights, and a shrinking foreign policy workforce have concerning implications for planning and carrying out U.S. global health programs. Such difficulties for global health have been compounded by certain policy decisions, including proposals to significantly cut U.S. global health funding (see Figure 2).

The most concrete global health policy change of the administration to date came on the first Monday of President Trump’s term, in the form of a re-instatement and expansion of the Mexico City Policy. The Policy, which was in effect and applied to family planning assistance in previous Republican administrations, was not only re-instated but also expanded to encompass almost all global health assistance, increasing the number of organizations and the amount of funding affected by the policy. We found the expanded policy applies to more than $7 billion in funding and likely affects more than one thousand foreign NGOs. In addition, on March 30 the administration invoked the “Kemp-Kasten amendment” to withhold funding for the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), the lead U.N. agency focused on global population and reproductive health, as has been done in previous Republican administrations.

The administration’s request to significantly cut global health funding is unprecedented. For FY2018 the White House proposed cuts of over $2B to global health, representing a 23% overall reduction compared to FY2017; these included a proposed reduction to PEPFAR of more than $1 billion and a zeroing out of the family planning budget, among others. Multiple analyses of the potential impacts of such cuts conclude that serious negative health consequences would result, including many more infections and deaths from HIV and TB, and an increase in the number of abortions along with greater maternal mortality. None of these requested cuts have been enacted but this is the first time cuts of this magnitude have been proposed, and they mark a significant shift from the direction and emphasis of prior administrations.

Even as they have implemented more restrictive policies and proposed cuts, Trump Administration officials have publicly stated support for select U.S. global health priorities. In his first major speech to the United Nations in September, for example, President Trump highlighted three major U.S. global health areas of success: PEPFAR, the President’s Malaria Initiative, and the Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA). Secretary of State Tillerson has also spoken about the importance of PEPFAR and the GHSA; the U.S. has signaled its intention to remain engaged in the larger GHSA effort, and has even highlighted the importance of global health security in the newly revised U.S. National Security Strategy, and is expected to do the same in a forthcoming national biodefense strategy. Despite the foreign policy vacancies noted above, some global health and development leaders have remained in their roles since the Obama Administration, including the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator and the Director of the National Institutes of Health, while other key positions have been filled by President Trump, including the new USAID Administrator who has a strong record in global health, the Director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and leadership on global health within the White House National Security Council.

Congress Pushes Back

Congress has also continued to play a significant role in global health, including bipartisan and bicameral push back against proposed funding cuts. Funding for global health was kept at FY 2017 levels and, while not yet final, will likely be level in FY2018 as well. Moreover, Congress has asserted its role in directing global health efforts by including, for the first time, language in the FY 2017 budget legislation that prevents the administration from changing global health program funding levels. Congress also included language requiring a report before any reorganization of State and USAID could occur. Many stakeholders, including current and former U.S officials, the faith community, and members of the military, have also pushed back on the administration’s proposed cuts to global health and development.

U.S. Public Support for Global Health Continues, Though with Some Declines & Partisan Divisions

Our latest (January 2018) tracking poll assessed public support for U.S. engagement in global health in the Trump era. The public perceives the Trump Administration as less supportive of global health, with half (53%) saying the Trump Administration has made global health a lower priority than previous administrations.

As mentioned above, about half of the public (54%) say they want the U.S. to play a leading or major role in improving health for people in developing countries. Support for such engagement is strongest among Democrats (73%), who also are more likely to support the U.S. playing “a leading role” (20%), and lower among independents (47%) and Republicans (49%), see Figure 3; Trump supporters are not interested in the U.S. playing a leading role (just 4% say they believe this). However, overall support fell slightly from 2016, when 61% said they think the U.S. should take a leading or major role.

Most of the public (59%) believe the U.S. is spending the right amount or not enough on global health programs, but one-third (33%) believe the U.S. is spending too much – a significant jump from the 18% saying we were spending too much in 2016.

For overall global engagement, the poll numbers indicate a greater proportion of the U.S. public (69%) now believes the U.S. should take at least a major role in solving the world’s problems than in 2016 (57%). The share of Republicans agreeing with this statement grew from 20% in 2016 to 31% in 2018. However, confusion about the amount spent on U.S. foreign aid persists, with half (49%) saying too much is spent in this area but when presented with the actual amount – about 1% of the federal budget goes to foreign aid – people are much less likely (29%) to view that as too much spending (as found in previous polls). See Appendix and poll results for more detailed information.

PROGNOSIS

The push and pull in global health policy will likely continue in 2018 and potentially intensify. On the one hand, actions taken by the administration signal a reduced U.S. engagement in the world and intention to step back further in global health. On the other, U.S. global health programs have so far demonstrated resilience, buoyed by strong support from Congress and key stakeholders.

The tension will likely be tested again in the near term with the soon-to-be released FY 19 White House budget request, which many expect to propose at least the same level of deep cuts to global health. Negotiations will take place within the broader context of greater budget pressures and concerns about the deficit, particularly in wake of recently enacted tax legislation that could tighten discretionary spending, including for foreign assistance, even more.

Beyond that, there will be a number of other issues to watch, including:

- Mexico City Policy: The expanded Mexico City Policy, which has only begun to be implemented, will likely be felt in a much more pronounced way in these next months and years including potential gaps in services in the field;

- PEPFAR: The administration, Congress, and other stakeholders are beginning to assess whether they want to move forward to reauthorize PEPFAR – the program’s current authorization expires at the end of FY 2018 (though the program will not end and a new reauthorization is not needed to keep it funded). In addition, PEPFAR’s recently launched new strategy, which aims to focus most efforts on 13 priority countries, raises questions about the larger U.S. global AIDS response in the context of potential budget decreases;

- Global Health Security Agenda: Key decisions about the next phase of the GHSA, including what to do regarding an impending fiscal cliff as supplemental Ebola funds expire in FY2019, will soon be coming down the pike and the U.S., as a founding and leading member of the partnership, will figure prominently in its future direction; and

- Replenishment: Two major global health multilateral partners of the U.S. – the Global Fund and GAVI – will soon begin processes for launching their next replenishment conferences, marking an important moment for gauging future U.S. support.

The key question going forward, then, may very well be which vision of global health will end up holding sway in the political back-and-forth in Washington – that of the White House or Congress? Ultimately, the winners, or losers, of this “battle” will be the people that benefit from U.S. investments around the world.