The Semi-Sad State of Consumer Protection In Health Care

It’s not likely that we are at a tipping point on consumer protection in health care, despite a hot news cycle just before the holidays, which rediscovered public angst about health insurance as expressed largely on social media following the murder of United Healthcare’s Brian Thompson. The reality is that there is little prospect of significant consumer protection legislation in Congress with the Trump administration and Republicans opposed to regulation in charge. States have some ability to enact consumer protection regulations, but the issues they take on are narrow and differ state by state, and they cannot touch self-insured plans, which cover 65% of workers.

It’s not likely that we are at a tipping point on consumer protection in health care, despite a hot news cycle just before the holidays, which rediscovered public angst about health insurance as expressed largely on social media following the murder of United Healthcare’s Brian Thompson. The reality is that there is little prospect of significant consumer protection legislation in Congress with the Trump administration and Republicans opposed to regulation in charge. States have some ability to enact consumer protection regulations, but the issues they take on are narrow and differ state by state, and they cannot touch self-insured plans, which cover 65% of workers.

So far, no president, Secretary of Health and Human Services, or member of Congress has seen the opportunity for a larger package of consumer protection reforms that is big or bold enough to grab media attention or appeal to voters. Instead, we are likely to see a patchwork of pinprick actions at the federal and state level. Progress, but whack-a-mole.

The news media did not over-hype the underlying frustration with the complexity and cost of health care following the Thompson murder, but it did sometimes conflate an outburst on social media—always from the most motivated or aggrieved—with the potential for policy change.

As an organization that has focused on consumer issues since we started, including through a program dedicated to addressing patient and consumer protections, wide-ranging polling on consumer issues, and regular reporting from our newsroom, the moment feels a little like how we rediscover gun violence periodically, then move on.

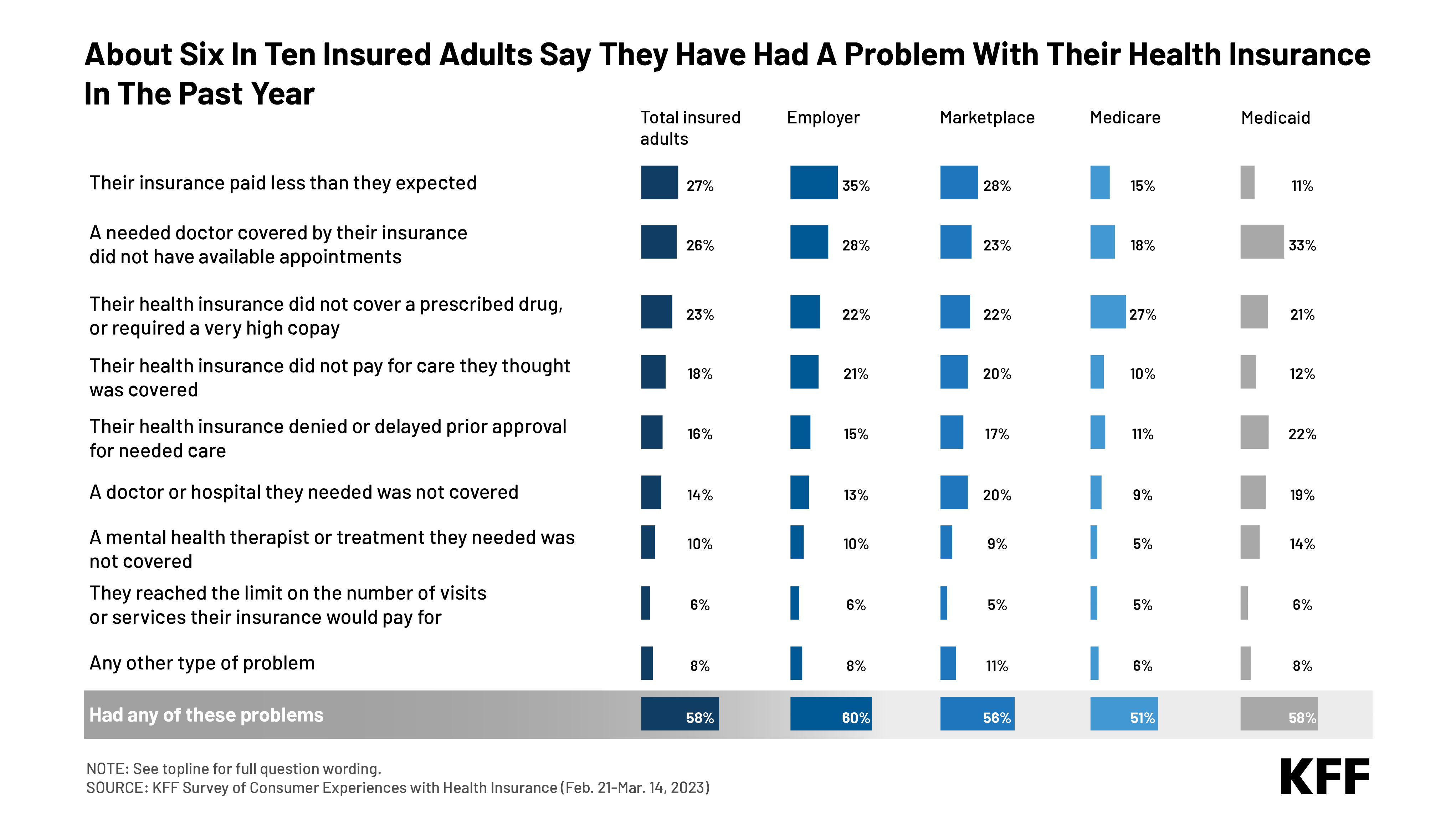

Nobody wakes up in the morning thinking warm and fuzzy thoughts about health insurance companies, and some people have had horrible experiences. The online reaction that followed Thompson’s assassination may at times have been macabre, but it was also reflective of real problems people have experienced with their health coverage and conveyed the real anguish those who are sick and cannot get the care they need can experience. More than half of insured Americans (58%), and even more people who are in ill health (67%), report problems with their coverage. This chart shows the problems people report from our big survey of consumer experiences. It’s not one thing; it’s “death by a thousand cuts” in a health system in which complexity is a feature, not a bug.

This is not entirely new. The so-called managed care backlash of the mid 1990s was the last major consumer flashpoint in health care. It stopped the growth of health maintenance organizations (HMOs) and led to the expansion of preferred provider organizations (PPOs). Frustration with HMOs centered around narrow networks and gatekeepers restricting access to care. HMOs have their loyal followers, but many people wanted to be able to choose their doctors and hospitals. Narrow networks are still an issue, as are incomprehensible bills and Explanation of Benefits (EOBs) and more, but frustration with PPOs centers around utilization management: prior-authorization review and denials. There are only limited data documenting it, but it feels like prior-authorization has become more restrictive and time-consuming for patients and physicians as insurers have hired outside organizations to take on the task, now with the assistance of AI. We are certainly seeing it at KFF with our PPO plan and its utilization management contractor, where even an organization full of health policy experts with PhDs sometimes struggle to navigate the system and gain approvals, often assisted by our human resources department, which has better things to do.

This is not entirely new. The so-called managed care backlash of the mid 1990s was the last major consumer flashpoint in health care. It stopped the growth of health maintenance organizations (HMOs) and led to the expansion of preferred provider organizations (PPOs). Frustration with HMOs centered around narrow networks and gatekeepers restricting access to care. HMOs have their loyal followers, but many people wanted to be able to choose their doctors and hospitals. Narrow networks are still an issue, as are incomprehensible bills and Explanation of Benefits (EOBs) and more, but frustration with PPOs centers around utilization management: prior-authorization review and denials. There are only limited data documenting it, but it feels like prior-authorization has become more restrictive and time-consuming for patients and physicians as insurers have hired outside organizations to take on the task, now with the assistance of AI. We are certainly seeing it at KFF with our PPO plan and its utilization management contractor, where even an organization full of health policy experts with PhDs sometimes struggle to navigate the system and gain approvals, often assisted by our human resources department, which has better things to do.

Another issue raised following Thompson’s murder has been the many ways in which utilization review meddles with the doctor-patient relationship, making their professional lives miserable and driving up their administrative costs. No question it does. And there is a serious question as to whether insurance companies should be the ones doing it, in a perfect world. They are anything but independent reviewers, with their own profits on the line. But our system is far from perfect and in our current health system there is no one else to do it (Mark Cuban has suggested third-party administrators could take on the task for self-insured plans and under some circumstances now, consumers can bring appeals to independent reviewers picked by employers, but seldom appeal in the first place). Imagine what costs and premiums would be with no checks on a mostly for-profit health system with every doctor, responsible and irresponsible, ordering every test drug and procedure they want to, regardless of whether it’s necessary or unnecessary?

Except, there actually is one world largely without utilization review: traditional Medicare. Instead, in one of health care’s great tradeoffs, Medicare pays providers a lot less than private insurance does to control costs. There is an age-old debate about whether Medicare pays too little (obviously the provider view) or private insurance, fragmented and too weak to bargain in many markets, pays too much (the view long championed, for example, by the late, great health economist Uwe Reinhardt in his popular speeches).

Many years ago, I wrote an op-ed in The New York Times wondering if the health professions would accept a grand bargain: lower payments closer to Medicare levels, in return for getting their professional autonomy back. The bargain then involved eliminating an old program called the Professional Standards Review Organization (PSROs), which physicians didn’t like. Today it might involve eliminating, or circumscribing, prior-authorization review in exchange for lower payments. I doubt health professionals, who fiercely resist payment cuts, would want the deal. Nobody likes tradeoffs.

Some things could be done to make things a little better for consumers, mostly through in-the-weeds changes: enforcing up-to-date directories of in-network physicians; making appeals processes more transparent and easier to use; establishing better criteria for using prior-authorization in the first place; so-called “gold card” programs for doctors who do not order unnecessary drugs or tests so they can bypass pre-authorization requirements for their patients; auto-renewal for authorization of ongoing care; independent review of denials for care for selected illnesses and chronic care; requirements that patients have a right to speak to a human (not a chatbot driven by AI); much better education and information for consumers who do not even know they can appeal denials; and more. There are also many consumer protections that have been legislated but not fully implemented. All of these “reforms” are small and none of them work perfectly in practice.

One idea I haven’t heard mentioned that has some merit is to require every insurer to have an internal ombudsman available to patients who advocates for them and reports to the CEO or the board, given that almost no consumers use current appeals mechanisms.

Several states passed targeted laws in 2024 to address prior authorization for the share of the market they can regulate. For example, Minnesota and Vermont exempted people with chronic conditions such as diabetes from prior authorization so long as their condition does not change. And Wyoming has a “gold card” program exempting physicians who are consistently approved by insurers.

Very modest legislation drafted in Congress to codify Medicare Advantage regulations on prior authorization fell out of the Continuing Resolution to keep the government open pretty early on in that drama. That legislation shows how piecemeal “reforms” can be in this area. It would have put into statute Biden administration regulations that shorten the timeframes for Medicare Advantage and other plans to make prior authorization decisions and facilitate the use of electronic exchange of information between insurers and providers for prior authorization. Another example of the hyper-incremental approaches we should expect to see is a new law just passed in California sponsored by my local state senator Josh Becker. His bill, the Physicians Make Decisions Act, requires that any denial of care be reviewed by a physician, an attempt to rein in denials triggered by AI algorithms. That’s a sensible and no doubt popular idea with unknown effects, since, of course, insurance company doctors deny care too.

One big thing that jumps out from the outrage and the opinion surveys is how skewed our priorities are in health care. I live in the Silicon Valley where daily I see the effort and money that goes into high-end innovation in health care and new digital technologies. But for average people it’s the basics that are broken: they can’t tell what their insurance covers and doesn’t; decipher their bill; get an appointment with a primary care doctor, let alone a specialist; appeal a coverage decision they feel is wrong; or even talk to a human with more compassion and nuance than they can find on their health system’s AI-assisted health system’s app.

We know costs are a problem, but for many people, it’s the complexity of the system that is equally daunting. So far, neither the complexity of the system nor the need to do more to protect consumers in it has found a champion. It could be a lost opportunity.