States Focus on Quality and Outcomes Amid Waiver Changes: Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2018 and 2019

Long-Term Services and Supports Reforms

| Key Section Findings |

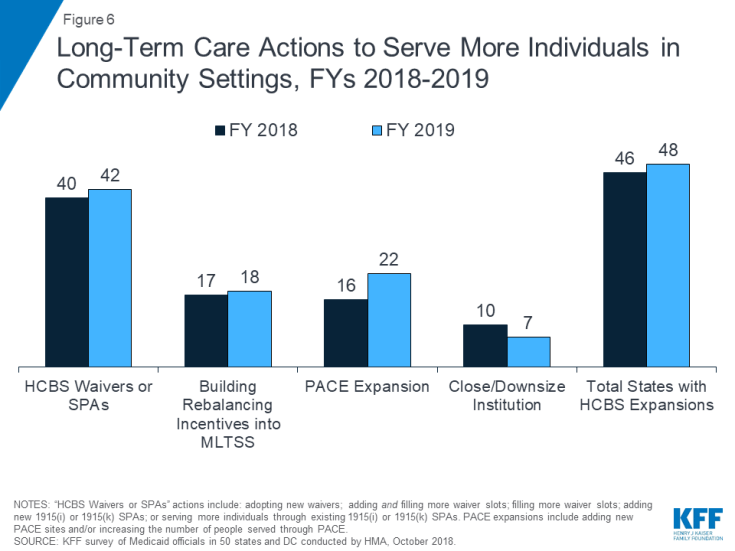

| Nearly all states in FY 2018 (46 states) and FY 2019 (48 states) are employing one or more strategies to expand the number of people served in home and community-based settings. A majority of states continue to report using HCBS waivers and/or state plan options (i.e., 1915(c), 1115, 1915(i), and 1915(k)) to serve more individuals in the community. As of July 1, 2018, 24 states covered LTSS through one or more capitated managed care arrangements.

What to watch:

Additional information on HCBS expansions implemented in FY 2018 or planned for FY 2019 as well as state-level details on capitated MLTSS models can be found in Tables 9 and 10.

|

Medicaid is the nation’s primary payer for long-term services and supports (LTSS), covering a continuum of services ranging from home and community-based services (HCBS) that allow people to live independently in their own homes or in other community settings to institutional care provided in nursing facilities (NFs) and intermediate care facilities for individuals with intellectual disabilities (ICF-IDs). In federal fiscal year 2016, spending on Medicaid LTSS totaled $167 billion, and HCBS represented 57% of these expenditures. In recent years, growth in Medicaid LTSS expenditures has been largely concentrated in HCBS. In 2016, spending on HCBS grew by 10% while spending on institutional LTSS decreased 2%.1

This year’s survey shows the vast majority of states in FY 2018 (46 states) and the vast majority of states in FY 2019 (48 states) are using one or more strategies to expand the number of people served in home and community-based settings (Figure 6). States were asked about their use of the following rebalancing tools/methods: use of HCBS waivers and/or State Plan Amendments (SPAs) (including 1915(c), Section 1115, 1915(i), and 1915(k)); use of rebalancing incentives in managed care contracts; use of Programs of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE); and efforts to downsize state institutions. A large majority of states in FY 2018 (40 states) and in FY 2019 (42 states) reported adopting new HCBS waivers/SPAs and/or serving more individuals through existing HCBS waivers/SPAs. About a third of states reported using rebalancing incentives in managed care contracts and about the same share reported implementing PACE expansions in FY 2018 and FY 2019. Fewer states report efforts to downsize state institutions. Table 9 shows state use of selected LTSS rebalancing tools in FY 2018 and FY 2019.

Few states reported actions to reduce or restrict the number of persons served in home and community-based settings in FY 2018 or in FY 2019. In FY 2018, Missouri increased the state’s institutional level of care standard, which affected the eligibility of 445 waiver participants upon reassessment and of over 1,200 waiver applicants on pre-assessment screening. In FY 2019, Michigan may reduce the number of slots available under its MI Choice 1915(c) waiver, which serves seniors and adults with physical disabilities, to reflect available funding.

| Tennessee Rebalancing Incentives in MCO Contracts |

| Tennessee pays its MLTSS health plans a blended capitation rate for older adults and adults with physical disabilities who meet Nursing Facility (NF) level of care (LOC) and are receiving services in a NF or HCBS. First, the state develops actuarially sound rates for each service setting. The mix of individuals receiving services in each setting (NF vs. HCBS) is determined and a target is established for how the percentages are expected to change during the rating period. The two capitation rates are blended according to those percentages, resulting in a single capitation payment for all persons who meet NF LOC. This is done separately for the dual eligible and the non-dual populations in each region. Because reimbursement is the same for NFs or HCBS, there is an incentive to serve people in the community whenever possible (both delaying or preventing NF placement as well as transitioning from NF placement to the community when appropriate). MCOs are also incentivized to ensure that services in the community are sufficient to meet the person’s needs since they are at financial risk for the higher cost NF placement. |

In this year’s survey, states were also asked to identify the most significant rebalancing challenges they currently face. Among states that responded, the challenges most frequently cited included lack of affordable and accessible housing, gaps in community-based provider capacity (especially in rural areas) and/or direct care workforce shortages, reimbursement challenges (e.g., rising and/or more favorable rates paid to nursing facilities compared to HCBS providers and the need to risk adjust rates as patterns of utilization change), and the expiration of the Money Follows the Person (MFP) program.

LTSS Direct Care Workforce

Many states are struggling to find sufficient numbers of trained direct care workers to meet the demand for services, including the demand for care in home and community-based settings.2,3 Low wages, few benefits, limited opportunities for career advancement, inadequate training, and high rates of worker injury are factors that also contribute to a workforce shortage and high workforce turnover among paid LTSS direct care workers. The National Center for Health Workforce Analysis projects that demand for direct care workers (including nursing assistants, home health aides, personal care aides, and psychiatric assistants/aides) could grow by 48% between 2015 and 2030, growth that is expected to far exceed the available workforce.4

To address LTSS direct care workforce shortages and turnover, increasingly states are reporting implementing wage increases and workforce development activities (Exhibit 13). In FY 2018, 15 states reported implementing wage increases for Medicaid-reimbursed direct care workers, while 24 states report implementing wage increases in FY 2019 (14 states in both years). In addition, 12 states had direct care workforce development strategies (e.g., recruiting, training, credentialing) in place in FY 2018, and 10 states reported expanding or implementing new workforce development strategies in FY 2019 (Exhibit 13).

| Exhibit 13: Strategies to Address LTSS Direct Care Workforce Shortages & Turnover | |||

| Fiscal Year | # of States | States | |

| Wage Increases | 2018 | 15 | AZ, CA, CO, CT, MA, MD, MI, MT, NH, NY, TN, UT, VT, WA, WI |

| 2019 | 24 | AZ, CA, CO, CT, DE, HI, IL, MA, MD, MI, MN, MT, NC, NJ, NY, OK, OR, TN, UT, VA, VT, WA, WI, WV | |

| Workforce Development (including recruiting, training, credentialing etc.) |

In Place FY 2018 |

12 | AZ, CA, CT, MA, NH, NY, OR, PA, SC, TN, WA, WI |

| New/Expanded FY 2019 | 10 | AR, AZ, IA, MN, NC, PA, TN, VT, WA, WI | |

| LTSS Direct Care Workforce Initiatives – State Examples |

|

HCBS Benefit Changes

More states reported actions to add or enhance HCBS benefits than states reporting actions to reduce or restrict HCBS benefits in FY 2018 and FY 2019. HCBS benefits include those in Section 1915(c) or Section 1115 waivers, under Section 1915(i) authority or Section 1915(k) authority (“Community First Choice” or “CFC”), PACE, and state plan personal care services, home health services, or private duty nursing. Eighteen states in FY 2018 and 26 states in FY 2019 reported a wide variety of HCBS benefit additions or expansions (Exhibit 14). Most HCBS benefit changes reported involve the addition of HCBS services to existing waiver or state plan programs. Examples of HCBS services added by states include new housing-related services or embedded post-MFP community transition services in HCBS authorities; changes to increase access to respite services or to provide training for family, consumers, and unpaid caregivers; enhanced transportation services; and pest eradication services.

A few states implemented new HCBS programs in FY 2018 or FY 2019. In FY 2018, Idaho added a new 1915(i) state plan program for children to offer respite and person-specific planning supports. Maryland added two new 1915(c) waivers to provide family and community support for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD). In FY 2019, California will implement a new 1915(i) program that will add housing access, family support, and other services for individuals with I/DD. Rhode Island proposes to add a Section 1915(k) Community First Choice program, and Alaska plans to add a new Section 1915(k) program. Seven states reported adding new PACE sites in both FY 2018 and FY 2019. Nine additional states will add new PACE sites in FY 2019 (Exhibit 14).

| Exhibit 14: HCBS Benefit Enhancements or Additions | ||||

| Benefit | FY 2018 | FY 2019 | ||

| HCBS Enhancements or Additions to Existing HCBS Authority | 12 States | CA, LA, MA, MI, MN, OH, PA, RI, SC, TX, UT, VA | 15 States | CO, HI, ID, IN, MA, MI, NC, ND, NM, NY, OH, PA, SD, TN, VA |

| New Section 1915(c), (i), or (k) | 2 States | ID, MD | 3 States | AK, CA, RI |

| New PACE Sites Added | 7 States | CA, MI, NJ, NY, OR, PA, WA | 16 States | AR, CA, CO, DC, DE, FL, IN, MI, NC, ND, NJ, NY, OR, PA, TX, WA |

| Rhode Island Proposed Section 1115 HCBS |

| Rhode Island is proposing to add additional preventive HCBS for target populations to further reduce or prevent the use of high cost services under its Section 1115 waiver renewal. Examples of new preventive services the state is proposing include home stabilization, peer support, chore services, and personal emergency response systems. The state also proposes to add services to its core HCBS, including but not limited to career planning, community transition, home stabilization, and training and counseling services for unpaid caregivers. |

Three states in FY 2018 (Missouri, Montana, and Oregon) and two states in FY 2019 (DC and Montana) implemented or plan to implement benefit changes that will reduce services under HCBS authorities. States reported targeted restrictions, noting they are being introduced to meet budget neutrality requirements or to reflect changes in available state funding. For example, DC proposes restricting the number of personal care assistance hours available under its Section 1915(i) elderly and persons with physical disabilities state plan option, and Montana is eliminating several services from its Section 1915(c) waivers for individuals with I/DD and those with severe disabling mental illness.5

Money Follows the Person and Housing Supports

Money Follows the Person (MFP) is a federal grant program, enacted under the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 and extended through September 2016 by the Affordable Care Act, which operated in 44 states.6,7 Enhanced federal funding under MFP has supported the transition of over 75,151 individuals from institutional to home and community-based long-term care settings as of December 2016.8 This includes the transition of older adults, individuals with physical disabilities, individuals with mental illness, and individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Although states are developing sustainability plans and completing tasks to close the current MFP grant program, states can use unexpended MFP grant funds through the end of federal FY 2020. However, a few states reported in this year’s survey that they have already exhausted their MFP grants.

Although many states are still developing sustainability plans and making determinations about whether and which services may continue, 30 states identified specific housing-related services that they plan to continue after MFP funding expires. With MFP resources, many states have offered new housing-related services, incorporated housing expertise within the Medicaid program to increase the likelihood of successful community living for persons who need supports, and engaged in strategic activities to assist in identifying and securing housing resources for individuals who choose HCBS.9 In this year’s survey, states were asked to describe housing-related services that will continue (under SPA or waiver authority) after the MFP funding expires.10 The most common services that states expect to continue are transition or relocation services (e.g., case management, coverage for one-time set up costs etc.) and services designed to help individuals locate and maintain housing in the community (e.g., tenancy supports, housing coordination, or supported housing).

About half of MFP-funded states anticipate they will have to discontinue services or administrative activities due to the expiration of MFP funding. States identified a wide range of services and key administrative functions that they expect to discontinue. Examples of services some states may discontinue include intensive transition case management, supportive living services, community transition/housing relocation services, transitional behavioral health supports, and residential environmental modifications. Examples of administrative functions some states may discontinue include statewide housing coordinator, local housing specialists, transition and outreach workers, options counseling, and assistance for individuals to access Section 811 vouchers.

Capitated Managed Long-Term Services and Supports (MLTSS)

As of July 1, 2018, almost half of states (24 states) covered LTSS through one or more of the following types of capitated managed care arrangements:

- Medicaid MCO covering Medicaid acute care and LTSS (20 states)

- PHP covering only Medicaid LTSS (6 states)

- MCO arrangement for dual eligible beneficiaries covering Medicaid and Medicare acute care and Medicaid LTSS services in a single, financially aligned contract under the federal Financial Alignment Demonstration (FAD) (9 states)

Of the 24 states that reported using one or more of these MLTSS models, nine states reported using two models, and one state (New York) reported using all three. Of the states with capitated MLTSS, 17 offered some form of MLTSS plan on a statewide basis for at least some LTSS populations as of July 1, 2018 (Table 10). Almost every MLTSS state includes both institutional and HCBS in the same contractual arrangement, while three states (California, Michigan, and Tennessee) report that this varies by MLTSS arrangement.

Nine states offered an MCO-based FAD (California, Illinois, Massachusetts, Michigan, New York, Ohio, Rhode Island, South Carolina, and Texas) as of July 1, 2018.11 The FAD model involves a three-way contract between an MCO, Medicare, and the state Medicaid program.12,13 Four states have requested an extension of the FAD beyond the current end date of the demonstration at the time of the survey (California, Massachusetts, Ohio, and South Carolina). Virginia closed its FAD at the end of calendar year 2017.

Many states encourage improved coordination and integration of services for the dually eligible population under MCO arrangements outside of the FAD. Massachusetts and Minnesota operate an administrative alignment demonstration (with no financial alignment) for some dually eligible beneficiaries. Nine states14 reported that they require Medicaid-contracting MCOs to be Medicare Dual Eligible Special Needs Plans (D-SNP)15 or Fully Integrated Dual Eligible (FIDE) Special Needs Plans16 in some or all MLTSS models offered in the state, creating an opportunity for improved coordination and integration for beneficiaries. Five states17 reported that they encourage MCOs to be a D-SNP or a FIDE-SNP.

MLTSS Enrollment

For geographic areas where MLTSS operates, this year’s survey asked whether, as of July 1, 2018, certain populations were enrolled in MLTSS on a mandatory or voluntary basis or were always excluded. On the survey, states selected from “always mandatory,” “always voluntary,” “varies,” or “always excluded” for the following dually eligible and non-dually eligible populations: seniors, persons with I/DD, and nonelderly persons with physical disabilities. Dual eligible and non-dual eligible seniors were most likely to be enrolled on a mandatory basis followed closely by persons with physical disabilities. Dual and non-dual persons with I/DD were most likely to be excluded from MLTSS enrollment. No state offering MLTSS always excludes full benefit dual eligible seniors or persons with physical disabilities from MLTSS enrollment (Exhibit 15).

| Exhibit 15: MLTSS Enrollment by Populations (# of States) | ||||||

| Non-Dual Eligibles | Dual Eligibles | |||||

| Seniors | Persons w/ Physical Disabilities | Persons w/ I/DD | Seniors | Persons w/ Physical Disabilities | Persons w/I/DD18 | |

| Always mandatory | 16 | 15 | 7 | 18 | 17 | 7 |

| Always voluntary | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| Varies | 3 | 3 | 8 | 3 | 3 | 8 |

| Always excluded | 4 | 4 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

MLTSS Population Changes

In FY 2018, Pennsylvania implemented MLTSS, with a plan to phase-in statewide over time, and Virginia ended its FAD but adopted statewide MLTSS for a wider population, including dual eligible individuals. Also, one state, Arkansas, reported that it will implement a capitated model of MLTSS for the first time in FY 2019 when it plans to adopt a global payment approach for its new “PASSE” program that provides comprehensive services, including personal care and other HCBS specialty services, for individuals who have the need for an intensive level of community based behavioral health or developmental disabilities services. While the state will exempt individuals who are receiving services under the DD waiver from this model, individuals who are on the waiting list for waiver services will be enrolled, as well as individuals who reside in private ICF-IDs.

In total, two states expanded the geographic reach of MLTSS in FY 2018 and five states are expanding MLTSS geographically in FY 2019 (Exhibit 16). Also, four states added previously excluded populations to MLTSS arrangements in FY 2018 and five states will add previously excluded populations in FY 2019. In all states except for South Carolina (where the state is expanding voluntary enrollment options under its FAD to all Medicare Advantage enrolled seniors statewide), the new populations covered are subject to mandatory enrollment. Rhode Island reported ending its MLTSS contract for individuals who opt out of the FAD, effective September 2018. After that date, individuals who opt out of the FAD will return to Medicaid fee-for-service.

| Exhibit 16: MLTSS Population Expansions, FY 2018 and FY 2019 | ||

| FY 2018 | FY 2019 | |

| Geographic Expansions | ID, MA | ID, IL, MA, PA, SC |

| New Population Groups Added | FL, ID, NY, VA | ID, NY, OH, PA, SC |

| Implementing an MLTSS program for the First Time | PA | AR |

Table 9: Long-Term Care Actions to Serve More Individuals in Community Settings in all 50 States and DC, FY 2018 and FY 2019

| States |

Sec. 1915(c)

or Sec. 1115

HCBS Waiver |

Sec. 1915(i) HCBS State Plan Option | Sec. 1915(k) “Community First Choice” Option | Building Rebalancing Incentives into MLTSS | PACE (* indicates new sites) |

Close/ Downsize Institution | Total States with HCBS Expansions | |||||||

| 2018 | 2019 | 2018 | 2019 | 2018 | 2019 | 2018 | 2019 | 2018 | 2019 | 2018 | 2019 | 2018 | 2019 | |

| Alabama | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Alaska | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Arizona | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Arkansas | X | X | X* | X | X | |||||||||

| California | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X* | X* | X | X | X | X | |

| Colorado | X | X | X | X | X | X* | X | X | ||||||

| Connecticut | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| DC* | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X* | X | X | ||||

| Delaware | X* | X | ||||||||||||

| Florida | X | X | X | X | X* | X | X | |||||||

| Georgia | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Hawaii | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Idaho | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Illinois | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Indiana | X | X | X | X | X | X* | X | X | ||||||

| Iowa | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Kansas | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Kentucky | ||||||||||||||

| Louisiana | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Maine | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Maryland | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Massachusetts | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Michigan | X | X | X | X | X | X* | X* | X | X | |||||

| Minnesota | ||||||||||||||

| Mississippi | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Missouri | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Montana | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Nebraska | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Nevada | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| New Hampshire | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| New Jersey | X | X | X* | X* | X | X | ||||||||

| New Mexico | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| New York | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X* | X* | X | X | X | X |

| North Carolina | X* | X | ||||||||||||

| North Dakota | X | X | X* | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Ohio | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Oklahoma | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Oregon | X | X | X | X | X* | X* | X | X | ||||||

| Pennsylvania | X | X | X | X | X* | X* | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Rhode Island | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| South Carolina | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| South Dakota | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Tennessee | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Texas | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X* | X | X | |||

| Utah | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Vermont | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Virginia | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Washington | X | X | X | X | X* | X* | X | X | X | X | ||||

| West Virginia | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Wisconsin | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Wyoming | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Totals | 40 | 40 | 12 | 14 | 8 | 9 | 17 | 18 | 16 | 22 | 10 | 7 | 46 | 48 |

| NOTES: “1915(c) or Sec. 1115 Waiver” actions include: adopting new waivers; adding and filling more waiver slots; or filling more waiver slots. Actions under “1915(i) and 1915(k)” include adding new 1915(i) or 1915(k) SPAs or serving more individuals through existing 1915(i) or 1915(k) SPAs. Actions under PACE include more individuals served in existing and/or new PACE sites, with an * indicating which states expect new sites in FY 2018 or FY 2019. NY noted they will add one or more PACE sites in FY 2018 and FY 2019 but also indicated enrollment in PACE has declined.

SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation Survey of Medicaid Officials in 50 states and DC conducted by Health Management Associates, October 2018. |

||||||||||||||

Table 10: Capitated MLTSS Models in all 50 States and DC, as of July 1, 2018

| States | Medicaid MCO | PHP | Financial Alignment Demonstration (FAD) for Duals |

Any MLTSS | Statewide |

| Alabama | |||||

| Alaska | |||||

| Arizona | X | X | X | ||

| Arkansas | |||||

| California | X | X | X | ||

| Colorado | |||||

| Connecticut | |||||

| Delaware | X | X | X | ||

| DC | |||||

| Florida | X | X | X | ||

| Georgia | |||||

| Hawaii | X | X | X | ||

| Idaho | X | X | |||

| Illinois | X | X | X | ||

| Indiana | |||||

| Iowa | X | X | X | ||

| Kansas | X | X | X | ||

| Kentucky | |||||

| Louisiana | |||||

| Maine | |||||

| Maryland | |||||

| Massachusetts | X | X* | X | ||

| Michigan | X | X | X | X | |

| Minnesota* | X* | X | X | ||

| Mississippi | |||||

| Missouri | |||||

| Montana | |||||

| Nebraska | |||||

| Nevada | |||||

| New Hampshire | |||||

| New Jersey | X | X | X | ||

| New Mexico | X | X | X | ||

| New York | X | X | X | X | X |

| North Carolina | X | X | X | ||

| North Dakota | |||||

| Ohio | X | X | X* | ||

| Oklahoma | |||||

| Oregon | |||||

| Pennsylvania | X | X | |||

| Rhode Island | X | X | X | X | |

| South Carolina | X | X | |||

| South Dakota | |||||

| Tennessee | X | X | X | X | |

| Texas | X | X | X | X | |

| Utah | |||||

| Vermont | |||||

| Virginia | X | X | X | ||

| Washington | |||||

| West Virginia | |||||

| Wisconsin | X | X | X | X | |

| Wyoming | |||||

| Totals | 20 | 6 | 9 | 24 | 17 |

| NOTES: States were asked whether they cover long-term services and supports through any of the following managed care (capitated) arrangements as of July 1, 2018: Medicaid MCO (MCO covers Medicaid acute + Medicaid LTSS); PHP (covers only Medicaid LTSS); MCO arrangement for dual eligibles under the Financial Alignment Demonstration (Medicaid MCO covers Medicaid and Medicare acute + Medicaid LTSS). *ID operates a PHP that covers LTSS in conjunction with an Medicare Advantage plan in selected counties and expects to expand to new counties in FY 2018 and FY 2019. *MA operates a FAD and a separate administrative alignment-only demonstration for dually eligible beneficiaries. *MN operates an administrative alignment-only demonstration for dually eligible beneficiaries using an MCO arrangement. *OH offers a Medicaid MCO (MCO offers Medicaid acute + Medicaid LTSS) only in those counties where the FAD is offered; dually eligible seniors who opt out of the FAD must enroll in this Medicaid MCO model for Medicaid services.

SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation Survey of Medicaid Officials in 50 states and DC conducted by Health Management Associates, October 2018. |

|||||