Medicaid's Most Costly Outpatient Drugs

Introduction

With its list price of $84,000 per treatment, the launch of the hepatitis C drug Sovaldi in December 2013 garnered the public’s and policymakers’ attention and brought into the spotlight the issue of high-cost prescription drugs in the U.S. Most Americans now believe that prescription drugs are too expensive.1 With over 70 million beneficiaries,2 the Medicaid program is larger than any other public or private insurer.3 Many Medicaid beneficiaries have poorer health than enrollees in private coverage4 and need prescription drugs to manage their medical conditions. As a result, Medicaid prescription drug spending is sizeable: in 2014, Medicaid spent $27.3 billion on outpatient drugs.5 Over the years, states have implemented an array of measures to control utilization and spending for prescription drugs.6

In this issue brief, we look at which outpatient prescription drugs were most expensive to Medicaid in 2014 and 2015 and explore why. As described in more detail in Appendix B, we merge state drug utilization data (available from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, or CMS) with Wolters Kluwer Clinical Drug Information (WKCDI) data to determine the 50 most costly outpatient drugs to the Medicaid program from January 2014 through June 2015 in terms of aggregate spending before rebates.7 Then, using WKCDI as well as data from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), we focus on common attributes among them and discuss policy implications.

Background

The Medicaid outpatient prescription drug benefit is not a mandatory benefit, but all states provide this benefit in their Medicaid programs. Typically, a Medicaid beneficiary receives a prescription from their physician and fills it at a pharmacy. Medicaid either reimburses the pharmacy for the prescription or pays a capitation fee to a managed care company that reimburses the pharmacy for the prescription.8 States then collect rebates for the drugs prescribed to their beneficiaries from the manufacturers and share this with the federal government.9 As a result of the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program created by Congress in 1991, all drug manufacturers must enter into a rebate agreement with the Secretary of Health and Human Services in return for Medicaid reimbursement for their prescription drugs.10 The rebate program was put into place to control the rising cost of drugs within Medicaid.11

In the early 2000s, as Medicaid spending for prescription drugs grew, states implemented a number of cost control measures in this area, such as supplemental rebates, preferred drug lists, and generic substitution. With the implementation of Medicare Part D (and the shift of drug costs for dually eligible beneficiaries from Medicaid to Medicare), Medicaid saw a large decline in prescription drug spending, and state activity in this area slowed.12 However, after years of slow growth, Medicaid spending on outpatient prescription drugs jumped 24% in 2014 to $27.3 billion, or about 6 percent of Medicaid spending.13 This increase in the growth rate is in large part due to increased enrollment resulting from Medicaid expansion and new high cost hepatitis C drugs.14

In January 2016, CMS released the Covered Outpatient Drugs final rule, which details drug reimbursement provisions outlined in the ACA, some of which were put into place to help states control drug spending. One such provision is the requirement that states must base drug ingredient cost reimbursement to pharmacies on the actual price of the drug, as opposed to using list prices.15 The previously used ingredient cost reimbursements, referred to as “Estimated Acquisition Costs,” often relied on “commercially published reference prices” which did not necessarily represent the actual cost of the drug to the pharmacy and were therefore susceptible to being manipulated.16 Many states had already made the change to using actual acquisition costs prior to the final rule.17 Despite this policy change, some drug manufacturers may still have the leverage to charge a high price for a drug due to lack of competition.

As states continue to grapple with controlling Medicaid prescription drug spending, many are focusing on high-cost “specialty drugs.” In FY 2015, over two-thirds of the states reported actions to refine and enhance their pharmacy programs in response to new and emerging specialty and high-cost drug therapies.18 However, it is unclear what role specialty drugs—or other types of drugs— play in Medicaid prescription drug spending. This analysis examines which drugs are the most costly to Medicaid and looks at common attributes of the most costly drugs. This information may be helpful as states undertake policy actions to balance high costs with high needs.

What Makes a Drug a High Cost to the Medicaid Program?

Aggregate drug costs to Medicaid reflect both frequency of use and per prescription costs. Among the most commonly prescribed outpatient prescription drugs in Medicaid, the top five drugs are used for pain relief (hydrocodone-acetaminophen and ibuprofen), management of chronic illness (lisinopril and omeprazole), and antibiotics (amoxicillin) (see Appendix Table A3). However, these drugs are not necessarily among the most costly to Medicaid as many are inexpensive at the per prescription level. Similarly, many drugs that are quite costly at the per prescription level are not commonly used by Medicaid enrollees. These drugs, which include drugs to treat hemophilia (NovoSeven RT, Koate-DVI, Feiba), multiple sclerosis (HP Acthar), and rare infant diseases (Adagen), reflect Medicaid’s role in caring for individuals with substantial health needs.

When we examined which drugs were high cost by assessing total Medicaid spending by drug name for each outpatient drug provided from January 2014 through June 2015,19 Abilify, Sovaldi, Vyvanse, Harvoni, and Truvada top the list, respectively (see Appendix Table A1). These are drugs to treat costly illnesses for which Medicaid is a key source of coverage, including behavioral health conditions (Abilify and Vyvanse), hepatitis C (Sovaldi and Harvoni), and HIV (Truvada).

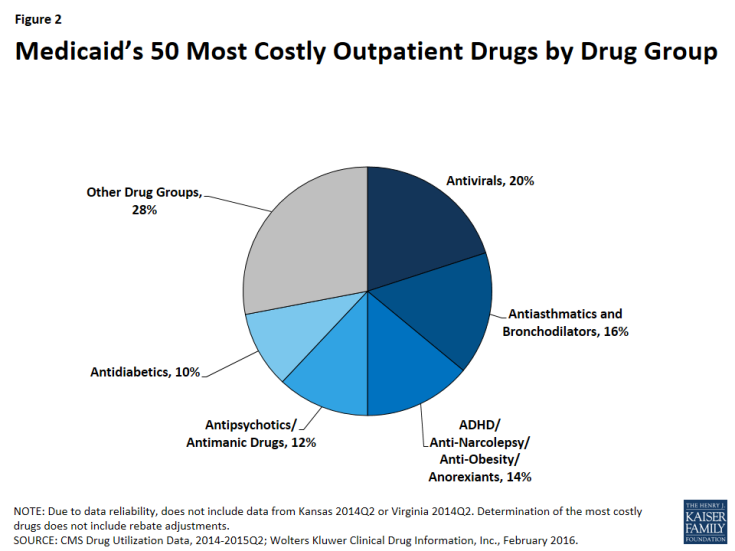

In Figure 1, we classify the 50 most costly (in aggregate) drugs in terms of how frequently prescribed and how expensive they are at the prescription level. If they are in the top 10th percentile of drugs by number of prescriptions, we identify them as “frequently prescribed.” If they were in the top 10th percentile of drugs by spending per prescription, we refer to them as an “expensive at the prescription level.”

Figure 1: Medicaid’s 50 Most Costly Outpatient Drugs by Prescription Level and Cost at the Prescription Level

We found that of the 50 most costly drugs, 45 fall into the high-cost category at least in part because they are very frequently prescribed. Over half (28) are frequently prescribed but not expensive at the prescription level. Among others, these drugs include treatments for ADHD and hydrocodone-acetaminophen, the most frequently prescribed drug in Medicaid over this period (Appendix Table A3 and “Case Study A: Opioids”).

A smaller number of the 50 most costly drugs (17) are both frequently prescribed and expensive prescriptions. Seven antiretrovirals included among the 50 most costly drugs fall into this group (Truvada, Atripla, Prezista, Stribild, Complera, Reyataz, and Isentress). Among others, this category also includes Abilify, an atypical antipsychotic and the most costly drug to Medicaid (Appendix Table A1), and Humira Pen, a drug used to treat arthritis.

The five remaining drugs are expensive at the prescription level but not in the top tenth percentile by prescriptions, and thus we have not defined them as being frequently prescribed.20 Among others, these drugs include the hepatitis C agents Sovaldi and Harvoni.

| Case Study A: Opioids |

| Two opioids are included in Medicaid’s 50 most costly drugs. Hydrocodone-acetaminophen (the generic version of Vicodin), an opioid, is the most frequently prescribed drug in Medicaid over the January 2014 through June 2015 period and is among the 50 most costly drugs over that period (Appendix Tables A1 and A3). Although it provides relief to those experiencing severe pain, it also may be addictive.Also included in the 50 most costly drugs is Suboxone, another opioid used for the treatment of opioid use disorder. Suboxone is the brand-name for the combination drug buprenorphine/naloxone and is intended to be taken as a pill under the tongue; if administered intravenously, the naloxone produces opioid withdrawal symptoms as a deterrent for misuse. Both hydrocodone-acetaminophen and Suboxone fall into the top 50 most costly drugs due to their wide use; neither is in the top 10th percentile of spending per prescriptions. In fact, hydrocodone-acetaminophen is the least expensive drug at the prescription level among the 50 most costly drugs.

As a drug class, opioids were the second most prescribed drug group over the period of study and the most prescribed drug group in 2014 (data not shown). This high level of opioid prescriptions reflects the high level of use of opioids in the U.S. overall, which has been drawing more and more concern in recent years. More than six in ten drug overdoses in the U.S. involve an opioid and since 1999, opioid deaths overall and prescription opioid deaths in particular have quadrupled.21 The high rate of use, including the misuse and abuse, of opioids affects a cross-section of society. More than half of Americans know someone who has died from opioids, has been addicted to them or knows someone who has been, or has taken painkillers that were not prescribed for them or knows someone who has.22 Medicaid patients are prescribed opioids at twice the rate as other patients, and their risk of overdose is three to six times higher than other patients.23 States and the federal government are taking action to address this public health crisis (see Policy Implications) and one of the ways they are doing so is through the expansion of medication-assisted treatments, which is the use of FDA-approved medications such as Suboxone24 in combination with behavioral therapy. |

Which Drugs are High Cost to Medicaid?

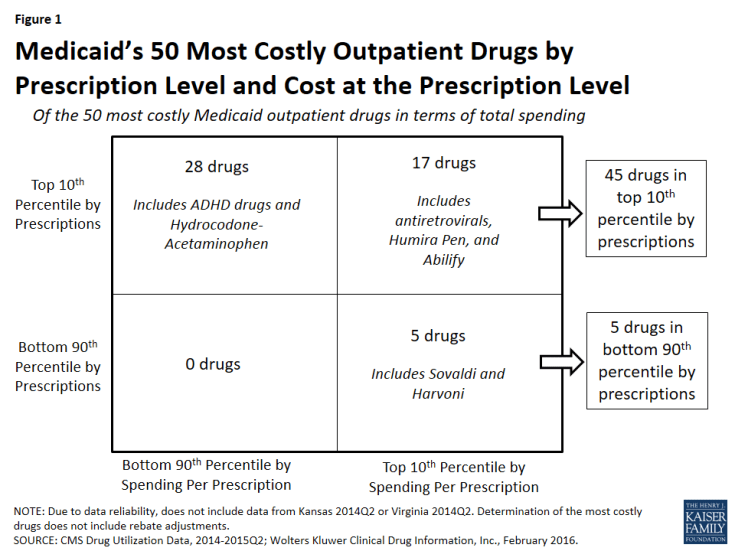

As shown in Figure 2, 72% (36) of the 50 most costly drugs are in five drug groups. Antivirals are the most common drug group among the most costly drugs, accounting for 20% of the top 50 drugs. The antivirals comprise seven antiretrovirals (drugs that are used primarily in the treatment of HIV), two hepatitis C agents, and one other type of antiviral. Reflecting the Medicaid population’s serious health needs, antiretrovirals are widely used in the program.25 Antiretrovirals are also costly on a per prescription basis. Hepatitis C agents are also costly on a per prescription basis but are not as frequently prescribed (Figure 1).

Antiasthmatics and bronchodilators are the second most common drug group in the 50 most costly drugs, accounting for 16% of the top 50 drugs. These are drugs used in the treatment of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). None of these drugs are among the most expensive per prescription, but all are very frequently prescribed.26

With 14% (7), ADHD/Anti-Narcolepsy/Anti-Obesity/Anorexients are the third most common drug group in the most costly drugs. Although the drug group implies that these drugs can be used for a variety of conditions, the seven drugs within this drug group all have a common indication of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Like the antiasthmatics and bronchodilators, all of these drugs are frequently prescribed and none of them are as expensive at the prescription level (Appendix Table A1). This high prescription rate is in part attributable to the high incidence rate of ADHD/ADD among children in general, among children in Medicaid, and among foster children in Medicaid.27

Twelve percent (6) of the most costly drugs are antipsychotics. Abilify, the most costly drug to Medicaid, is included within this group. Five out of the six antipsychotics in the 50 most costly drugs are both frequently prescribed and expensive at the prescription level (Appendix Table A1). Antipsychotics are FDA-approved to treat schizophrenia and bipolar disorder; however, they are also frequently prescribed “off-label” for other conditions.28

At ten percent, antidiabetics are the fifth most common drug group among the most costly drugs, with five drugs in this class falling into the top 50 most costly Medicaid drugs. Four of these five antidiabetics are insulins. None of the antidiabetics are in the top tenth percentile of drugs by spending per prescription, although the price of insulin has been increasing in recent years.29 All antidiabetics are very frequently prescribed, reflecting the high number of people in Medicaid who have diabetes: prior to Medicaid expansion, about four million Medicaid beneficiaries were diagnosed with diabetes.30

| Case Study B: Hepatitis C Agents |

| Hepatitis C is a bloodborne virus that often remains asymptomatic in a person for many years or decades but ultimately can cause cirrhosis and cancer of the liver. As many as 5.2 million people in the U.S. have the hepatitis C.31 It disproportionately affects baby boomers and those enrolled in public coverage programs including Medicaid, Medicare, the VA, and state and federal prison systems.32 The prevalence of hepatitis C among Medicaid beneficiaries reflects that the Medicaid population in general has higher health needs than those who are privately insured.33After the FDA approved it in December 2013,34 Gilead Sciences launched hepatitis C agent Sovaldi at a list price of $84,000 per treatment. Sovaldi is taken in combination with another antiviral, usually ribavirin.35 In October 2014, the FDA approved Gilead’s Harvoni, which does not require another drug to be taken in combination with it,36 and has a list price of $94,500 per treatment. Sovaldi and Harvoni are Direct-Acting Antivirals, which are “breakthrough-therapies,” as the previous standard treatment had a much lower cure rate as well as serious side-effects.37 Although they attracted attention in large part because of their high cost, Sovaldi and Harvoni are not the most expensive outpatient drugs to Medicaid at the prescription level on the market (Appendix Table A2).

In response to the high aggregate cost of these drugs, a majority of state Medicaid programs implemented various restrictions to accessing hepatitis C agents, many of which were based on the progress of the disease in the patient. States have also required alcohol and drug use screenings, consultation with a specialist, once-in-a-lifetime treatment maximums, and favorable viral response to the initial treatment.38 In 2014, only 2.4% of Medicaid enrollees with hepatitis C were able obtain to Sovaldi, in part due to states’ actions.39 State Medicaid programs are permitted to require prior authorization, implement prescription limits, and exclude drugs that are prescribed for a purpose other than their indication. However, they are not permitted to ultimately exclude access to a covered outpatient drug prescribed in accordance with its labeling for a treatment where that drug is an improvement compared to other covered outpatient drugs in terms of “safety, effectiveness, or clinical outcome[s].”40 CMS has expressed concern over the manner in which state Medicaid programs are restricting these drugs, reminding them that they may only restrict covered outpatient drugs in ways consistent with statute.41 A number of lawsuits have been filed against different state Medicaid agencies alleging that the restrictions on hepatitis C treatments are illegal and have caused harm to the plaintiffs.42 In May 2016, a federal court ordered the Washington state Medicaid program to lift the disease severity restrictions on hepatitis C treatments, marking the first time that a federal court declared such state Medicaid program restrictions to hepatitis C drugs illegal.43 Shortly after, in response to legal action and threatened legal action, Florida and then Delaware each announced in June of 2016 that Medicaid beneficiaries with hepatitis C would have access to needed medication, regardless of their stage of liver damage.44 |

How Does Market Exclusivity Affect Price?

In the absence of competition, a manufacturer may be able to price a drug higher. Patents and regulatory exclusivity, put into place as an incentive for innovation, are ways that a manufacturer can protect their product against competition. Patents have a twenty year duration, but manufacturers generally obtain them while their product is in preclinical and clinical trials, well before the FDA approves their product and well before the product launches. As a result, the duration remaining on the manufacturer’s original patent once the drug launches is usually much shorter than 20 years.45 Separate from the patent system, a manufacturer is also able to obtain regulatory exclusivity for their product from the FDA. Many of the 50 most costly drugs have some form of regulatory exclusivity.

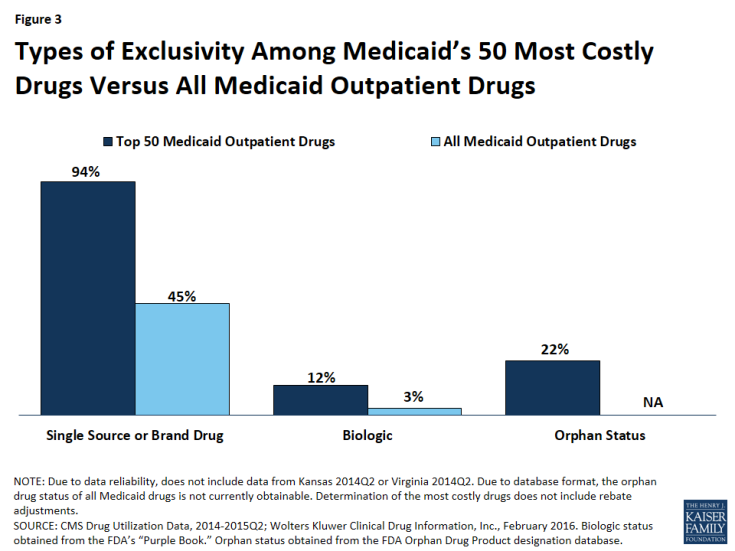

Figure 3: Types of Exclusivity Among Medicaid’s 50 Most Costly Drugs Versus All Medicaid Outpatient Drugs

| Case Study C: Abilify |

| Abilify was Medicaid’s most costly drug from January 2014 through June 2015. It is an atypical antipsychotic,46 as are all of the antipsychotic drugs included in the 50 most costly drugs. The FDA approved Abilify in 2002.47 It is used in the treatment of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, and Tourette syndrome, and for symptoms of autistic disorder. Despite receiving two black-box warnings,48,49 doctors prescribed it and other atypical antipsychotics for additional diagnoses, such as anxiety and insomnia.50 Abilify was to lose patent protection in the spring of 2015, but shortly before that was to happen, the FDA approved it for the treatment of Tourette syndrome. Abilify’s manufacturer made efforts to stave off generic entry by trying to obtain an orphan drug designation for this new indication that would have ensured exclusivity through 2021, but ultimately they were unsuccessful, and the FDA-approved generic version of Abilify came onto the market in 2015.51 In the face of this loss of patent protection, its manufacturer increased the price of the drug, a strategy often seen before a brand drug’s patent expires.52 |

Brand Versus Generic Drugs

A brand drug is generally considered to be a drug that has received FDA approval after the manufacturer has proven the drug’s safety and efficacy. The FDA awards a regulatory exclusivity period of 3 or 5 years to brand drugs.53 Regulatory exclusivity provides the manufacturer with a degree of market exclusivity, enabling them to price the drug accordingly and providing incentive for them to market it as a non-commodity, which includes naming the drug with appealing brand name. Alternatively, a manufacturer can obtain FDA approval for their drug by proving that it is bioequivalent to a brand drug,54 skipping the long and expensive process of proving a drug is safe and effective. The FDA identifies these drugs as generic.55 They cannot enter the market while the corresponding brand still has exclusivity.56 Once generic drugs enter the market, the price of the drug usually falls due to competition.

Compared to all drugs reimbursed through Medicaid from January 2014 through June 2015, we found a disproportionate number of the 50 most costly drugs are brands, as opposed to being generics (Figure 3).57 Ninety-four percent of the 50 most costly drugs were available as brand-name drugs, compared to 45% of all drugs reimbursed by Medicaid.

Biologics

A biologic is a drug that is derived from an animal or microorganism. It is more complex than traditional small-molecule drugs synthesized in a lab.58 Because biologics are structurally very different from small molecule drugs and are approved through a different process,59 there was not automatically a structure in place for generic approvals resulting in an absence of a generic market to commoditize biologic drugs. However, as part of the ACA,60 biologics now have 12 years of regulatory exclusivity,61 with an abbreviated pathway for the biosimilars, the biologic equivalent of a generic, now in place. Although biosimilars are expected to lower the price of the original biologic, they are not expected to lower it to that degree that generics lower the price of the original small-molecule brand drug.62 In March 2015, the FDA approved its first biosimilar, Zarxio, and the drug launched the following September.63

We found that 12% (6) of the 50 most costly drugs in Medicaid were biologics, compared with 3% of outpatient drugs reimbursed through Medicaid overall (Figure 3). The 6 biologics in the 50 most costly drugs are Humira Pen (used to treat psoriasis and some types of arthritis), Synagis (used to prevent serious lung disease), Advate (used in the treatment of hemophilia), Enbrel SureClick (used to treat psoriasis and some types of arthritis), Neulasta (used to treat possible side effects of chemotherapy), and NovoSeven RT (used in the treatment of hemophilia). All of these 6 biologics are in the top 5th percentile in terms of Medicaid spending per prescription. Twenty-nine of the 50 most expensive drugs by spending per prescription are biologics, showing that although these drugs are often very expensive, they do not necessarily appear as large budget items for Medicaid because of lower utilization (Appendix Table A2).

Orphan Drugs

The FDA provides orphan drug designations to drugs that treat fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S. or those that treat a disease for which the manufacturer does not expect to recover the cost of the drug.64 Having an orphan drug designation entitles the sponsor to many benefits,65 including a seven-year period of regulatory exclusivity associated with the drug’s indication. The 1982 Orphan Drug Act has generated an increase in the number of drug designations targeting rare diseases.66 However, some argue that it is being used to create blockbuster drugs, as manufacturers slice more common diseases into subtypes affecting fewer than 200,000 Americans and gain an orphan drug designation for a subtype, with the drug ultimately being used widely for other conditions.67

We found that 22% (11) of the 50 most costly drugs had achieved an orphan drug designation at some point (Figure 3). This includes Abilify, the most costly drug to Medicaid. Nine of these 11 drugs were among Medicaid’s top 10th percentile of most prescribed drugs.

Specialty Drugs

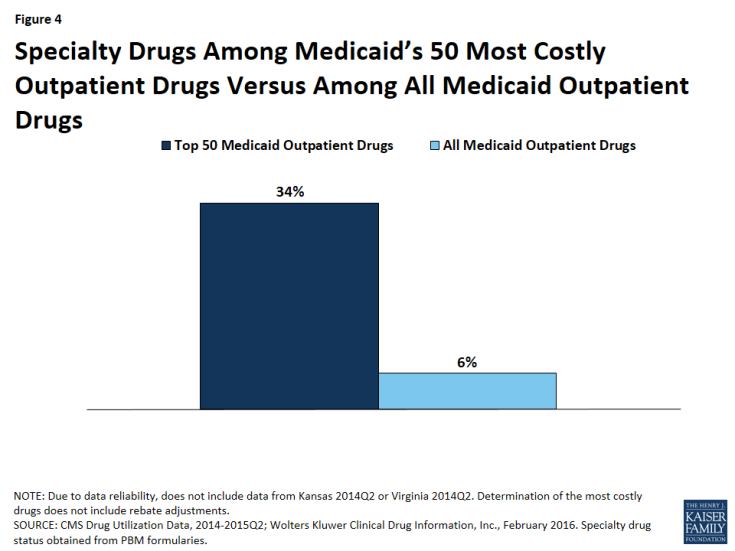

Although there is not one universally accepted definition, a specialty drug is generally considered to be a drug that requires difficult or unusual handling or is for a difficult-to-treat disease. Price is also often an indicator of a specialty drug.68 We found that a disproportionate number of drugs in the 50 most costly drugs are considered specialty drugs based on formulary review, with 34% (17) of the most costly drugs being considered specialty drugs, compared to 6% of all Medicaid covered outpatient drugs (Figure 3). Given that price factors into whether a drug is considered a specialty drug, it is not entirely surprising that so many of the most costly drugs are specialty drugs, and that many have a type of regulatory exclusivity. Of the 17 specialty drugs in the most costly drugs, none are multi-source generics (Appendix Table A1), and all but one are only available as branded single-source products with one labeler (data not shown). Six of the 17 specialty drugs are biologics, meaning that all biologics among the most costly drugs are considered specialty drugs (Appendix Table A1).

Figure 4: Specialty Drugs Among Medicaid’s 50 Most Costly Outpatient Drugs Versus Among All Medicaid Outpatient Drugs

Policy Implications

In this analysis, we found that although all of the most costly drugs to Medicaid are frequently prescribed, expensive at the prescription level, or both; a majority are frequently prescribed. Access to prescription drugs is crucial for the treatment of many conditions found in the Medicaid population, which is more likely to have health issues than the privately insured. Although the prescription drug benefit is not mandatory for states, all state Medicaid programs provide it to their Medicaid beneficiaries. However, it can be expensive, and states are forced to grapple with the costs of the benefit. Additionally, although state Medicaid programs may know a new drug is coming to market, they may not have a sense for how expensive it will be until it reaches the market. States have taken a number of actions to control the budgetary effects of high cost drugs, including implementing new prior authorization requirements and negotiating higher supplemental rebates and lower prices for certain drugs.69

Balancing Cost with Access

Often, drugs that are high-priced are “orphan drugs” that treat rare diseases, which are allowed longer exclusivity so that the manufacturer can earn a profit on the drug. Sovaldi and Harvoni attracted attention because they were priced like orphan drugs,70 but they are for diseases that are prevalent in the Medicaid population. As these drugs were coming to market, nearly all states expressed concern about how the cost of this treatment would affect their Medicaid spending.71 However, while high cost, these drugs are cures for most patients; they are more effective than the previous standard drug treatment for the disease;72 and a full treatment of Sovaldi or Harvoni is less costly than a liver transplant, 73 for which hepatitis C is the leading cause.74 It is important to take a broad view when considering prescription drug costs, as many costly drugs prevent expensive emergency department visits and hospital stays. Regardless, states felt that it was not feasible to provide this drug to every beneficiary with hepatitis C immediately.75 In response, CMS published guidance reminding state Medicaid programs that certain utilization controls are permissible, but when doing so, states must ensure that they are in compliance with statute.76

In general, states can help control the overall costs of drugs by monitoring utilization and aiming to ensure that drugs are not overprescribed to patients. For example, states can require prior authorization or use a preferred drug list to control access. However, states generally must cover FDA-approved drugs for their medically accepted indications.77 States may not replace unreasonable limits on access to medically necessary drugs, such as those that are contrary to the professional standard of care. Many states have attempted to balance the public health need for hepatitis C drugs with their high cost through the implementation of prior authorization and other requirements.78 Spending and utilization for hepatitis C agents is lower than it would have been without these restrictions, but some beneficiaries who need these drugs are unable to access them, and a number of lawsuits have been filed against different state Medicaid agencies challenging state policies that limit access contrary to generally accepted standard of care among medical professionals.

Monitoring High Utilization

Many of the most costly drugs to Medicaid are so costly because they are frequently prescribed, including hydrocodone-acetaminophen, an opioid. While there are many medically necessary reasons to prescribe this drug, there is also a great deal of evidence to suggest overutilization of opioids. There is much that states can do to address the misuse of opioids, such as undertaking provider education; removing methadone79 from the preferred drug lists; establishing clinical criteria for obtaining a methadone prescription; requiring step therapy, prior authorization, or prescription quantity limits; using drug utilization review80 measures to identify potential misuse of opioids; increasing access to and use of prescription drug monitoring program data, and implementing patient review and restriction programs.81 States have acknowledged the severity of this public health crisis, and nearly all have prescription monitoring programs in place.82 There are hundreds of proposals in legislatures to regulate clinics and prescription behavior.83 The federal government has awarded money to health centers to focus on opioid abuse,84 and in March the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released opioid prescription guidelines.85 Also as part of its collection of Medicaid quality measures, CMS is beginning to collect information on the use of opioids from multiple providers among non-cancer patients.86

Opioids are not the only drug at risk of being overprescribed. Three of the seven ADHD/Anti-Narcolepsy/Anti-Obesity/Anorexients are amphetamines, which are stimulants and have a black box warning of “high potential for abuse.”87 There is also general concern over the use of antipsychotics among children enrolled in Medicaid. As part of its collection of Medicaid and CHIP quality measures, CMS is beginning to collect information on children prescribed more than one antipsychotic at a time.88 As states monitor opioid and other drug groups as a way to address public health needs, they may realize budget savings due to lower utilization as well.

Promoting Innovation

Although policy makers are concerned with the cost of the prescription drug benefit, they also are concerned with beneficiaries having access to cures and treatments, and part of enabling this is incentivizing the pharmaceutical industry to research and bring to market new and needed drugs. In the U.S., innovation in the pharmaceutical industry is incentivized through regulatory exclusivity. This analysis has shown that many high cost drugs have some form of regulatory exclusivity. As Congress searches for ways to encourage innovation, they also remain aware of the varying ability for different payers to sustain these incentives. Nonetheless, although different payers face different parameters than Medicaid when paying for prescription drugs, this struggle to balance incentivizing innovation with actually being able to pay for the prescribed drugs is not unique to Medicaid alone, but a common challenge across the entire U.S. health care system.