Medicaid’s Money Follows the Person Program: State Progress and Uncertainty Pending Federal Funding Reauthorization

|

Key Takeaways |

|

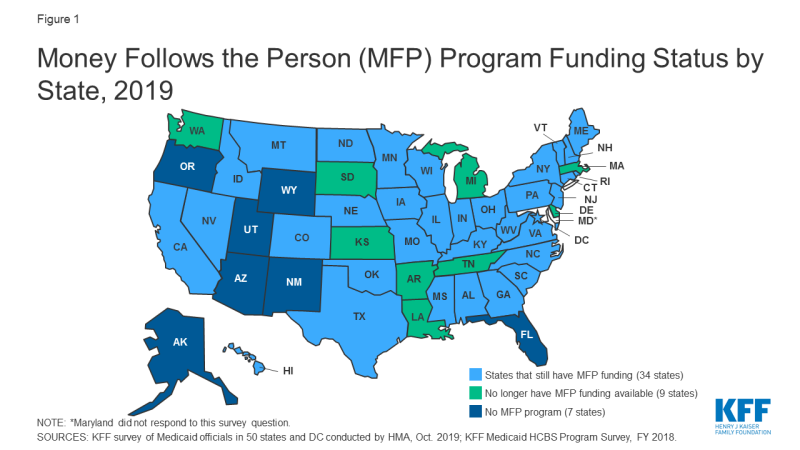

Medicaid’s Money Follows the Person (MFP) demonstration has helped seniors and people with disabilities move from institutions to the community by providing enhanced federal matching funds to states since 2007.1 The program operates in 44 states (Figure 1 and Table 1), and has served over 90,000 people as of June 2018.2 Box 1 below provides more information about the MFP population, services, and financing. MFP seeks to reduce the Medicaid program’s institutional bias, which exists because nursing facility services must be covered, while most home and community-based services (HCBS) are provided at state option. The program is credited with helping many states establish formal institution to community transition programs that did not previously exist by enabling them to develop the necessary service and provider infrastructure.3 It also has been a catalyst for states to develop housing-related activities as states have used MFP funds to offer housing-related services and hire housing specialists to help beneficiaries locate affordable accessible housing, which is routinely cited as a major barrier to transitions.4

With a short-term funding extension set to expire on December 31, 2019, MFP’s future remains uncertain without a longer-term reauthorization by Congress. MFP is a federal grant program created as part of the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005, and subsequently extended by the Affordable Care Act, with total funding increased to $4 billion.5 Although states were set to fully phase-out their MFP programs in federal fiscal year 2020, Congress has provided $254.5 million in additional funds in three short-term extensions of the program through December 2019.6 This issue brief highlights new data about the status of states’ MFP funding and the services and activities that would be affected if the program is not reauthorized. The brief draws on data from the Kaiser Family Foundation’s most recent 50-state Medicaid home and community-based services (HCBS) survey and 50-state Medicaid budget survey.

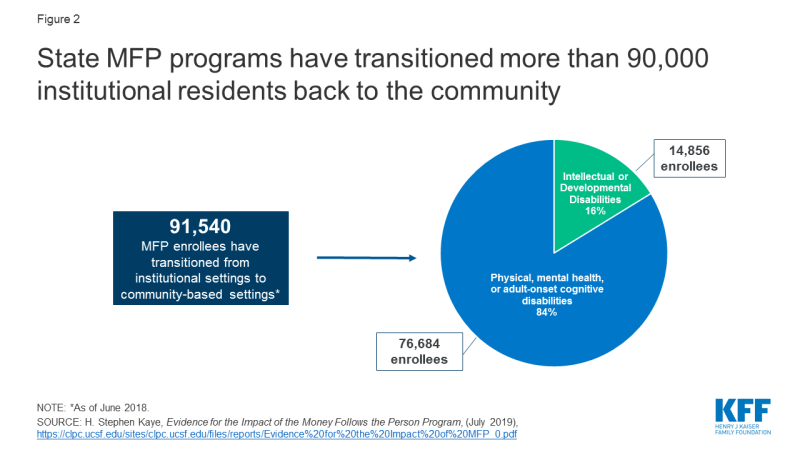

Figure 2: State MFP programs have transitioned more than 90,000 institutional residents back to the community

Box 1: MFP Enrollees, Services, and Financing

Over 90,000 people have moved from institutions to the community with support provided by MFP from 2007 through June 2018. Over 80 percent of MFP enrollees are people with physical, mental health, or adult-onset cognitive disabilities, and less than 20 percent are people with intellectual or developmental disabilities (I/DD) (Figure 2). While people with mental health disabilities comprise a small share of all MFP enrollees, states increasingly have focused on meeting this population’s typically greater needs as MFP programs became more established. One study shows a 77 percent increase in cumulative transitions for people with mental health disabilities in less than two years (1,790 in 2013 to 3,174 in mid-2015).7

MFP’s enhanced matching funds are available for HCBS to support beneficiaries during their first year in the community, after residing in an institution for more than 90 consecutive days. States receive an enhanced matching rate (within a range of 75% to 90%8) during the first year that an enrollee lives in the community for Medicaid HCBS that are covered through the state plan benefit package or a waiver. These services typically include personal care, adult day health, case management, homemaker, habilitative, and respite. States also receive the enhanced matching rate for “demonstration services,” which are additional HCBS provided during the enrollee’s first year in the community and in a manner or amount not otherwise available to Medicaid enrollees, such as transition coordination services or additional personal care hours. Enhanced matching funds are drawn down from the state’s MFP grant. From 2007 through 2016, states were awarded MFP grants ranging from nearly $6 million in South Dakota to nearly $400 million in Texas.9 Through MFP, states also provide services to help beneficiaries overcome barriers to returning to community living after residing in an institution for an extended period. These “supplemental services,” such as security and utility deposits and household set up costs, are not necessarily long-term care in nature and are reimbursed at the state’s regular matching rate.

States must use their enhanced matching funds for initiatives to shift their long-term care spending in favor of HCBS over institutional care. The activities most frequently financed by enhanced matching funds include expanding HCBS waiver capacity, providing access to transition services, improving access to affordable accessible housing, engaging in outreach, training direct care workers and medical providers, developing enrollee needs assessments, and supporting administrative data and tracking systems.10

Key Findings

Twenty percent (9 of 44) of MFP states will have exhausted their current funds by the end of 2019, and the vast majority of the remaining states expect to do so during 2020. Seven states (KS, LA, MA, MI, SD, TN, and WA) already have exhausted their MFP funds, and two more (AR and DE) expect to do so by December 2019 (Figure 1 and Table 1). Thirty-four states report they have not yet expended all of their MFP funds, although the vast majority of this group anticipates that their current funding will be exhausted during 2020.11

Over one-third (15 of 44) of MFP states identified a range of services and other program activities and staff positions that they expect to discontinue if federal funding expires (Table 1). Community transition services were most often cited as being at risk of discontinuing once MFP funds are exhausted. Other services that states expect to discontinue include community case management, housing relocation assistance, and family caregiver training. Program staff positions and activities that states expect to discontinue without additional federal funding include outreach specialists, housing specialists, and training for care coordinators and providers, among other activities. States use their enhanced matching funds to finance initiatives to expand HCBS, as described in Box 1 above, and may not be able to continue these activities if federal funding is lost.

Just over one-quarter (12 of 44) of MFP states already have added new services to existing HCBS waivers in anticipation of federal funding expiring (Table 1). These include 12 waivers serving seniors and people with physical disabilities, 11 waivers serving people with I/DD, three waivers serving people with brain injuries, and one waiver serving people with mental health disabilities. All of these states have added transition services (CO, DE, GA, ID, IN, MA, ND, OH, SD, VA, WA, and WV) to support individuals in the community up to a year after leaving an institution. In addition, Michigan has a Section 1915 (i) HCBS state plan amendment awaiting CMS approval to add transition services for seniors and adults with physical disabilities to replace MFP funding. Several states added other services to their waivers in addition to transition services. For example, Colorado added life skills training, home delivered meals, and peer mentorship to six waivers, Massachusetts added orientation and mobility services, Ohio added community integration services, and Washington added goods and services.

Eight states report plans to add new services to an existing HCBS waiver in anticipation of MFP funds expiring (Table 1). Among these states, four already have added some services to an existing waiver (described in the prior paragraph, GA, ID, IN, OH) and also now plan to add other services, while four states are making these plans for the first time (IA, NE, NJ, SC). Georgia plans to add transition services to its two waivers that do not already include these services. Iowa plans to add three new services, including crisis response, behavioral programming, and mental health outreach, to its waiver serving people with I/DD. Nebraska is exploring adding tenancy services to its waiver serving seniors and adults with physical disabilities. South Carolina plans to add expanded goods and services and transition coordination services to three waivers serving people with HIV/AIDS, seniors, and people with physical disabilities. Ohio is planning to add coaching support services and community integration support services to two waivers serving seniors and people with physical disabilities. NJ is seeking to expand community transition services to add one-time clothing purchase and one-time pantry stocking.

Looking Ahead

With the help of MFP enhanced federal matching funds, states have invested in building and maintaining their transition programs, serving over 90,000 seniors and people with disabilities who have received the services and supports to move from institutions to the community. The national MFP evaluation found that enrollees experienced significant increases in quality of life measures after leaving an institution, and these increases were sustained two years after moving to the community.12 HHS’s report to Congress on MFP noted that “any dollar value placed on these improvements would not adequately reflect what it means for people with significant disabilities when they can live in and contribute to their local communities.”13

The national MFP evaluation found that some individuals would not have transitioned without MFP. After five years of program operation, about 25 percent of older adult MFP enrollees and half of those with I/DD in 17 states would have remained institutionalized without MFP.14 Additionally, MFP enrollees were less likely to return to an institution compared to those who transitioned without MFP.15 Other research has found declines in nursing home occupancy rates and reductions in the number of nursing home residents who never expect to return to the community in states with “robust” MFP programs compared to states without MFP or with a “minimal” program.16 All of these findings show that MFP has contributed to tipping the balance of long-term services and supports (LTSS) spending, with spending on HCBS surpassing spending on institutional care for the first time in 2013, and comprising 57% of total Medicaid LTSS spending as of 2016.17 MFP also has helped states control per enrollee spending, as providing enrollees with HCBS typically costs less than institutional care.18 The national MFP evaluation found that state Medicaid programs realized $978 million in savings during the first year after transition for MFP enrollees through 2013, though all of these savings could not be attributed to MFP. 19

MFP’s future remains uncertain, with current funding exhausted by the end of 2019 in 20 percent of MFP states and most of the remaining states expecting to run out of funds during 2020. While some states have added certain HCBS funded by MFP to other Medicaid authorities in anticipation of the funding expiration, over one-third of MFP states report that some HCBS funded by MFP as well as staff positions to support transitions, such as outreach and housing coordinators, are at risk of ending when federal funding for the program expires. While MFP has contributed to state progress in rebalancing LTSS to date, support would need to be ongoing for states to maintain this progress, especially as the demand for LTSS is expected to grow as the population ages. States continue to report that lack of access to affordable and accessible housing and an inadequate supply of direct care workers are major barriers to serving more people in the community. While there are always competing demands on federal budget funding that could disrupt MFP, there is not a substantive debate over it as there is with many other health programs. However, if Congress does not reauthorize MFP, it could hinder state efforts to help beneficiaries move from institutions to the community.

| Table 1: States’ Money Follows the Person (MFP) Program Funding and Future Plans | |||||

| State | Has MFP Program | Exhausted MFP Funds | Plans to discontinue MFP services and/or program activities if federal funding not reauthorized | Already added MFP services to existing waiver | Plans to add MFP services to existing waiver |

| Alabama | X | ||||

| Alaska | N/A | ||||

| Arizona | N/A | ||||

| Arkansas | X | X | |||

| California | X | X | |||

| Colorado | X | X | X | ||

| Connecticut | X | ||||

| Delaware | X | X | |||

| DC | X | ||||

| Florida | N/A | ||||

| Georgia | X | X | X | ||

| Hawaii | X | ||||

| Idaho | X | X | X | ||

| Illinois | X | X | |||

| Indiana | X | X | X | ||

| Iowa | X | X | |||

| Kansas | X | X | |||

| Kentucky | X | ||||

| Louisiana | X | X | X | ||

| Maine | X | ||||

| Maryland | X | NR | |||

| Massachusetts | X | X | X | ||

| Michigan | X | X | X | * | |

| Minnesota | X | ||||

| Mississippi | X | TBD | |||

| Missouri | X | X | |||

| Montana | X | X | |||

| Nebraska | X | X | |||

| Nevada | X | X | |||

| New Hampshire | X | ||||

| New Jersey | X | X | |||

| New Mexico | N/A | ||||

| New York | X | X | |||

| North Carolina | X | ||||

| North Dakota | X | X | |||

| Ohio | X | X | X | ||

| Oklahoma | X | X | |||

| Oregon** | N/A | ||||

| Pennsylvania | X | ||||

| Rhode Island | X | ||||

| South Carolina | X | X | X | ||

| South Dakota | X | X | X | ||

| Tennessee | X | X | X | ||

| Texas | X | ||||

| Utah | N/A | ||||

| Vermont | X | TBD | |||

| Virginia | X | X | X | ||

| Washington | X | X | X | ||

| West Virginia | X | X | X | ||

| Wisconsin | X | ||||

| Wyoming | N/A | ||||

| TOTAL: | 44 | 7 | 15 | 12 | 8 |

| NOTES: N/A = not applicable. NR = no response to survey question. TBD = state’s plans to be determined. HCBS waivers include § 1915 (c) and § 1115. *Additionally, MI is adding services to a § 1915 (i) state plan amendment. **OR discontinued its MFP program in 2010. SOURCES: KFF survey of Medicaid officials in 50 states and DC conducted by HMA, Oct. 2019; KFF Medicaid HCBS Program Survey, FY 2018. |

|||||