Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility, Enrollment, Renewal, and Cost-Sharing Policies as of January 2016: Findings from a 50-State Survey

Medicaid and CHIP Enrollment and Renewal Processes

During 2015, states continued to implement system enhancements and adopt processes to implement the ACA’s vision of a modernized data-driven enrollment experience and a largely automated renewal process. Adoption of these procedures represents significant transformation and streamlining in many states that previously relied on paper-based enrollment and renewal processes for Medicaid and CHIP. As states continued work developing the information technology systems that underpin enrollment and renewal, their functionality increased as demonstrated by the growing number of states that are able to make real-time eligibility determinations and automatically renew coverage. Coordination between Medicaid and the Marketplaces also improved considerably in 2015, but there are lingering challenges to ensure smooth transitions between coverage programs for individuals.

Eligibility and Enrollment Systems

In order to implement the new enrollment and renewal processes outlined in the ACA, most states needed to make major improvements to or build new Medicaid and CHIP eligibility and enrollment systems and coordinate enrollment with the Marketplaces. To support system development, the federal government provided 90% federal funding for system design and development. This increased funding level was initially set to expire at the end of 2015, but CMS finalized a rule in December 2015 to extend the higher federal match permanently.1 The extension of this funding will support continued work in states that have not implemented enhanced system functionality to fully meet ACA requirements. It also will support continued state work to phase in additional capabilities and consumer features and keep systems current as technology evolves in the future. Higher functioning systems facilitate the ability to enroll and keep eligible individuals in coverage by reducing paperwork burdens and allowing individuals to manage more activities through an online environment. They also may contribute to increased administrative efficiencies. Moreover, as these systems and processes become more refined, they may enable states to manage larger enrollments more efficiently, allowing them to refocus resources on other services such as helping individuals understand how to use their health care services. They may also provide new tools and options to support program management, such as increased data reporting and data connections with other systems or programs.

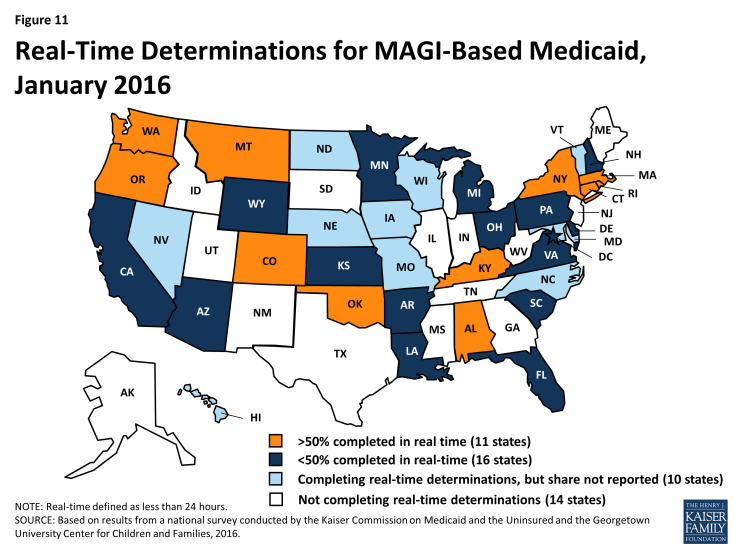

As of January 2016, 37 states can complete MAGI-based eligibility determinations in real-time (defined as less than 24 hours), and 11 states indicate that at least 50% of MAGI-based applications receive a real-time determination. Among the 27 states that were able to report the percentage of MAGI-based applications that receive a real-time determination, 11 states report a success rate that exceeds 50%, including 9 that report a rate over 75%. In the remaining 16 states, less than half of MAGI-based applications receive a determination in real-time (Figure 11). Looking ahead, many states will continue to work to increase the share of applications that receive a real-time determination.

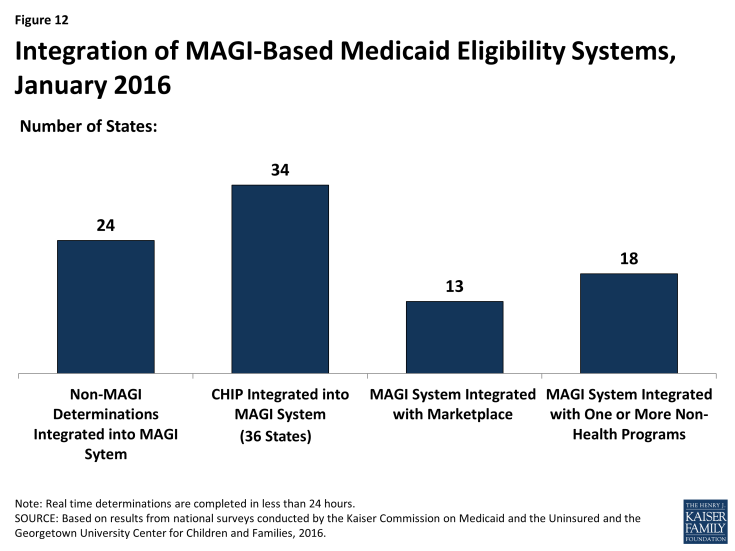

As of January 2016, states vary in the integration of other health programs in their MAGI-based Medicaid systems (Figure 12). During 2015, three states (Florida, Nebraska, and Virginia) integrated eligibility determinations for non-MAGI groups, which include elderly individuals and individuals with disabilities, into their MAGI-based systems. With these additions, 24 states process MAGI and non-MAGI groups through the same system as of January 2016. Most states with a separate CHIP program (34 of 36 states) have CHIP integrated into the MAGI-based system. Among the 17 states operating a State Based Marketplace (SBM), 13 have a single, integrated system that makes eligibility determinations for both MAGI-based Medicaid and Marketplace coverage. With Hawaii transitioning eligibility determinations from its SBM to the Federally Facilitated Marketplace (FFM) in 2015, 4 SBM states and the 34 FFM and Partnership states are using Healthcare.gov for Marketplace eligibility and enrollment functions as of January 2016. These 38 states all must maintain a separate Medicaid eligibility and enrollment system at the state level.

In 18 states, the MAGI-based Medicaid system is integrated with at least one non-health program, and a number of states are planning further integration in the future. Prior to the implementation of the ACA, 45 states had integrated systems to determine eligibility for Medicaid and other non-health programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP or food stamps), Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), and childcare assistance. As states upgraded or built new Medicaid eligibility systems, many delinked these programs from the Medicaid system due to the large scale of the changes. However, as of January 2016, 18 states had integrated at least one non-health program into their MAGI-based Medicaid system. Colorado delinked non-health programs from its Medicaid system when it integrated its Medicaid system with its Marketplace system in 2015. However, a number of states plan to phase in additional non-health programs into their Medicaid system in 2016 or beyond. The continuation of enhanced funding for system development, as well as flexibility provided by CMS that requires other programs to pay only the incremental integration costs, support these efforts. Although this flexibility was slated to end at the close of 2015, CMS extended it for three more years.2

Coordination between Medicaid and Marketplace systems improved considerably in 2015, but there are lingering challenges. In the 38 states relying on the FFM for Marketplace eligibility and enrollment functions, electronic accounts must be transferred between the federal and state systems to provide a coordinated, seamless enrollment experience for individuals as envisioned by the ACA. Such transfers are not necessary in the 13 SBM states with an integrated Medicaid and Marketplace eligibility system although, in some cases, data transfers must occur after the eligibility determination to complete enrollment. Among the 38 states relying on the FFM for eligibility and enrollment, 8 states have authorized the federal system to make final Medicaid eligibility determinations, which can expedite the enrollment process. However in these states, the FFM still must transfer accounts to the Medicaid agency to complete enrollment. The remaining 30 states allow the FFM to assess rather than determine Medicaid eligibility. These counts reflect three states (Louisiana, North Dakota, and Oregon) choosing to rely on the FFM for assessments rather than final determinations, and one state (Alaska) adopting the option for the FFM to make final determinations rather than assessments during 2015. States relying on the FFM for assessments must use the information received in the account transfer to determine eligibility based on the same verification requirements in place for individuals who apply directly through the state Medicaid agency. This process may require checking other data sources or requesting documentation for information that cannot be confirmed electronically. During 2014, there were significant difficulties with account transfers that contributed to delays in Medicaid enrollment. However, there have since been improvements in transfer functionality with all 38 states that rely on the FFM for Marketplace eligibility and enrollment functions reporting that they are receiving electronic account transfers from the FFM, and 36 states reporting that they are sending electronic account transfers to the FFM as of January 2016. A little more than half of these states (20 states) report they are still experiencing some delays or difficulties with transfers, although the scope of these challenges varies across these states.

Applications

Under the ACA, states must provide multiple methods for individuals to apply for health coverage, including online, by phone, by mail, and in person, using a single streamlined application for Medicaid, CHIP, and Marketplace coverage. The use of online applications, as well as online accounts, gives states new opportunities to offer features and functions that enhance individuals’ enrollment experience and expand their ability to manage their ongoing Medicaid coverage, which may help eligible individuals enroll and retain coverage over time. The increased use of technology may also provide administrative efficiencies to states by reducing paperwork and manual input of information that enrollees can report online, such as an address change. This growth in the use of technology has been supported by the 90% federal match for systems development and 75% federal match for ongoing operations that are now permanently available to states.

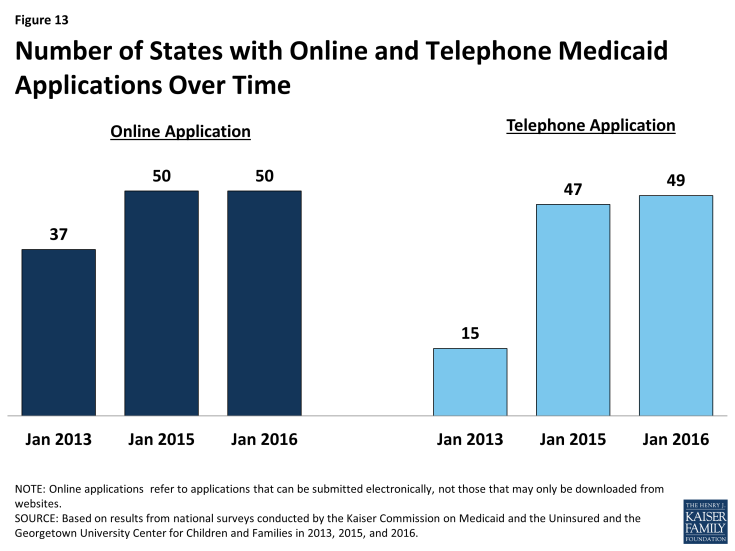

As of January 2016, individuals can apply online or by phone for Medicaid in nearly all states. In all states, except Tennessee, there is an online Medicaid application available through the state Medicaid agency or, in SBM states, an integrated portal that provides access to Medicaid and the SBM. In addition, 24 states offer an integrated online application that allows individuals to apply for Medicaid and non-health programs, such as SNAP or TANF. These states largely align with those states that have Medicaid and non-health programs integrated into a single eligibility system, although a few states are using separate eligibility systems to process multi-benefit applications. With the addition of Arkansas and Florida during 2015, 49 states are accepting Medicaid applications by phone as of January 2016. The number of states providing online and telephone Medicaid applications has significantly increased since initial implementation of the ACA changes in 2014 (Figure 13).

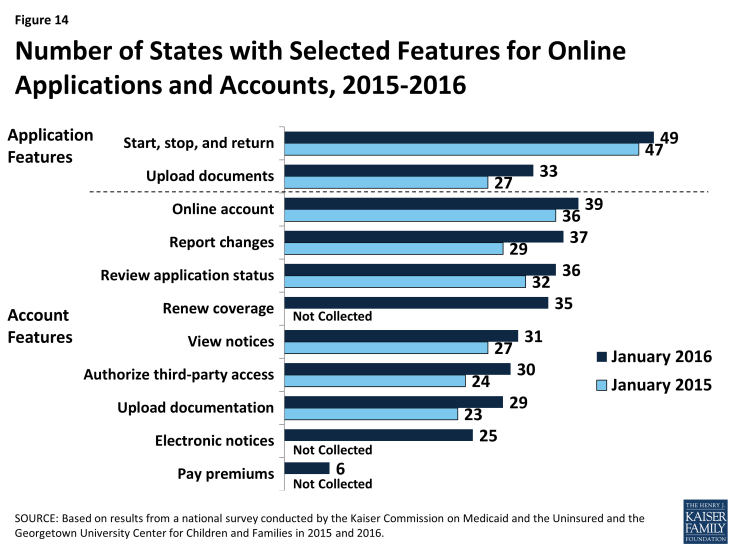

A number of states expanded the functionality of online applications and accounts during 2015. Between January 2015 and 2016, the number of states that provide applicants the option to start, stop, and return to complete their application at a later time increased from 47 to 49, while the number of states that allow applicants to upload electronic copies of documentation through the online application increased from 27 to 33 (Figure 14). In addition, the number of states that provide individuals the opportunity to create an online account for ongoing management of their Medicaid coverage rose from 36 to 39, with the addition of North Dakota, South Carolina, and South Dakota. A larger number of states added features to existing online accounts. Specifically, there were increases in the number of states that allow individuals to use their online account to report changes (29 to 37 states), review the status of their application (32 to 36 states), view notices (27 to 31 states), authorize third-party access (24 to 30 states), and upload documentation (23 to 29 states). This year’s survey also asked about additional account functionalities and found that individuals can use their account to renew coverage in 35 states, go paperless and receive electronic notices in 25 states, and pay premiums in 6 of the 32 states that charge premiums in Medicaid or CHIP. Additional states plan to add online accounts in 2016 or beyond, while states with online accounts plan to continue to add features. These online functions provide timely and convenient access to account information that is commonplace in today’s digital age, and may lead to administrative efficiencies by reducing mailing costs, call volume, and manual processing of updates. The ability for consumers to see and manage their application and information online also may contribute to increased enrollment and retention levels over time.

Nearly half of the states (24 states) provide a web portal or secure login for authorized consumer assisters to submit applications they have facilitated on behalf of consumers. In some cases, these portals provide additional administrative features that support the work of assisters, such as the ability to check a renewal date or update an address. Providing better tools for assisters may reduce state administrative workloads and free resources for other consumer services. This functionality may also allow the agency to track, monitor and report application activity by assister more thoroughly, accurately, and efficiently.

Verification of Eligibility Criteria

Under the ACA, all states must verify income eligibility and citizenship or immigrant status but they have flexibility to accept self-attestation for other criteria such as age/date of birth, state residency, and household composition. If verification is required, states are expected to use electronic data sources to the extent possible. Verifying eligibility criteria electronically is not only technically complicated, but requires the establishment of data sharing agreements between agencies to ensure that the privacy and security of personally identifiable information is protected. These challenges in accessing electronic data sources can slow state progress in implementing or maximizing real-time eligibility determinations and automated renewals without the intervention of an eligibility worker. However, as of 2016, a number of states are reporting success completing real-time eligibility determinations and automatic renewals that are facilitated through electronic data matches.

States are relying on a mix of data sources to electronically verify eligibility criteria. To facilitate electronic verification, a federal data hub was established that allows states to access information from multiple federal agencies, including the Internal Revenue Service, the Social Security Administration (SSA), and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), which is used by almost three quarters of states. States not using the federal hub rely on pre-ACA linkages to SSA and DHS databases. Nearly all states also use state databases that collect quarterly state wage information or unemployment compensation, which may contain more current income information. About half of the states also use information from their state vital records while a smaller number of states access information from other state databases, such as the Department of Motor Vehicles or State Tax Department.

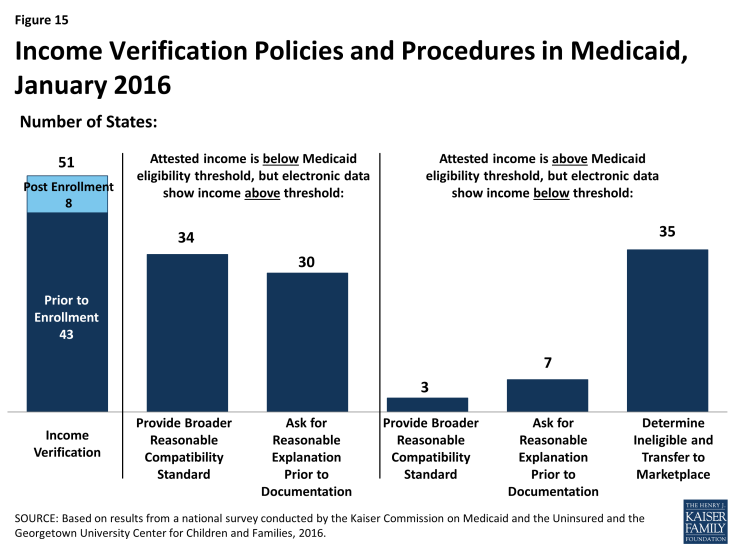

As of January 2016, 43 states use electronic data sources to verify income prior to enrollment, while 8 states verify after enrollment (Figure 15). States are required to verify income electronically either prior to or after enrollment and may apply “reasonable compatibility standards” to account for differences in self-reported income and data from electronic sources. If self-reported income and the data from the electronic source are both above or below the Medicaid or CHIP eligibility threshold, states must disregard the discrepancy since it does not impact eligibility. States have the option to establish broader reasonable compatibility standards, which 34 states have adopted for cases in which self-attested income is below but electronic data sources show income above the Medicaid or CHIP eligibility limit. If the difference is within this reasonable compatibility standard, which is most often 10%, states accept the self-reported income. In contrast, only three states (Colorado, Florida and New Jersey) have adopted a reasonable compatibility standard for when self-reported income is above the income standard but the electronic data source is below. In these circumstances, 35 states deny Medicaid or CHIP eligibility and transfer the account for an assessment of Marketplace eligibility. Regardless of whether they have set broader reasonable compatibility standards, states may accept a reasonable explanation of the difference (e.g., the individual lost a job) in lieu of requiring paper documentation.

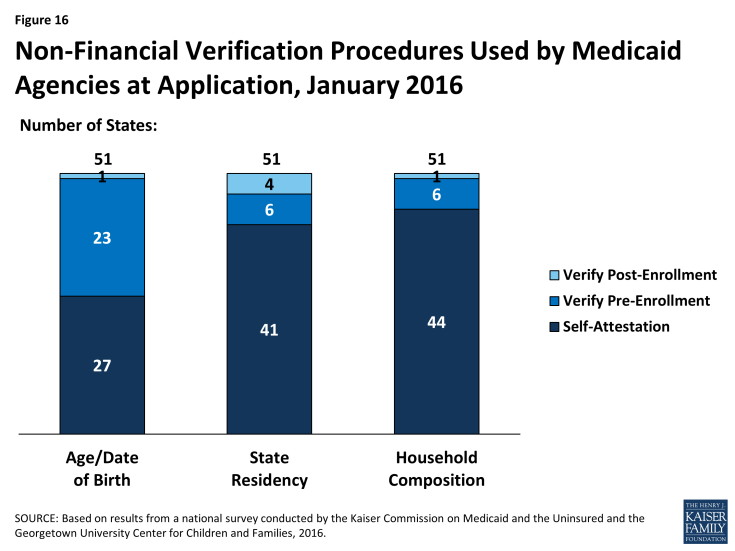

States’ procedures to verify non-financial eligibility criteria continue to evolve as their systems and electronic verification capacity develop. For non-financial eligibility criteria, including age/date of birth, state residency, and household composition, states may accept self-attestation or verify either before or after enrollment. Accepting self-attestation expedites the process for states and applicants, particularly when the state lacks access to trusted data sources that can be used for verification purposes. For states that rely on self-attestation, verification is required if a state has any information on file that conflicts with the self-attestation. As of January 2016, just over half of the states accept self–attestation of age/date of birth (27 states), while a majority of states do so for state residency (41 states) and household size (44 states) (Figure 16). The remaining states verify these eligibility criteria either prior to enrollment or post-enrollment, and about half of those states re-verify the information at renewal.

Figure 16: Non-Financial Verification Procedures Used by Medicaid Agencies at Application, January 2016

Facilitated Enrollment Options

States vary in their use of policy options to streamline enrollment. As states achieve high rates of real time eligibility determinations, the reliance on facilitated enrollment options may decline. However, there will always be some individuals who may benefit from expedited paths to enrollment since not all individuals will be able to have eligibility verified in real time. As of January 2016, states continue to rely on a range of these policy options to provide facilitated access to coverage as discussed below.

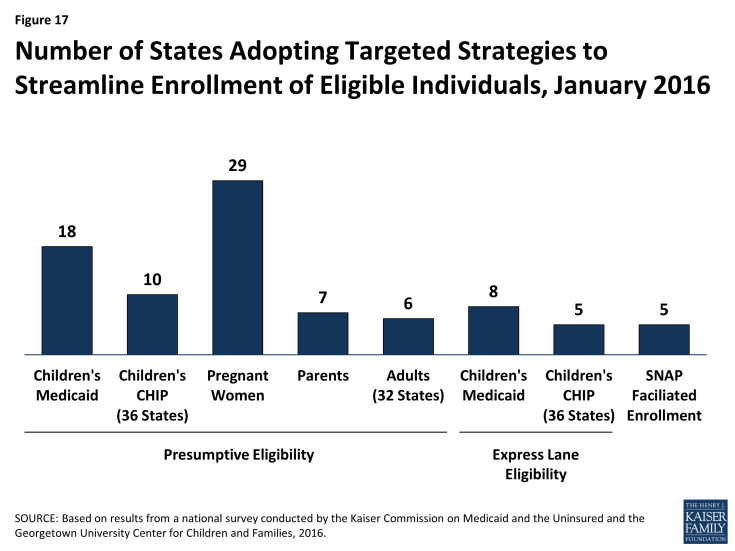

- Presumptive eligibility. Presumptive eligibility is a longstanding option in Medicaid and CHIP, which allows states to authorize qualified entities—such as community health centers or schools—to make a temporary eligibility determination to expedite access to care for children and pregnant women while the regular application is being processed. The ACA broadened the use of presumptive eligibility in two ways. First, the law allows states that use qualified entities to presumptively enroll children or pregnant women to extend the policy to parents, adults, and other groups. As of January 2016, 18 states use presumptive eligibility for children in Medicaid, 10 for children in CHIP, 29 for pregnant women, 7 for parents, and 6 for other adults (Figure 17). This count reflects expansion of the use of presumptive eligibility to parents and adults in Colorado and Montana; to children in Medicaid and CHIP, parents, and adults in Indiana; and to pregnant women in Kansas during 2015. Second, the ACA gives hospitals nationwide the authority to determine eligibility presumptively for Medicaid for all non-elderly, non-disabled individuals. Hospital-based presumptive eligibility has been implemented in 45 states as of January 2016.

Figure 17: Number of States Adopting Targeted Strategies to Streamline Enrollment of Eligible Individuals, January 2016

- Express Lane Eligibility. Express Lane Eligibility (ELE) is another pre-ACA option that allows states to enroll children in Medicaid or CHIP based on findings from other programs, like SNAP. During 2015, Oregon discontinued the use of ELE, while Iowa began using ELE to enroll CHIP eligible children. Following this state action, eight states (Alabama, Colorado, Georgia, Iowa, Louisiana, New Jersey, New York, and South Carolina) use ELE to enroll children in Medicaid, and five states (Colorado, Georgia, Iowa, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania) use ELE to enroll CHIP eligible children as of January 2016.

- Facilitated enrollment using SNAP data. In 2013, CMS offered states new temporary facilitated enrollment options, including using SNAP data to identify and enroll eligible individuals and using child enrollment data to expedite parent enrollment. In 2015, CMS made the SNAP facilitated enrollment option permanent.3 As of January 2016, five states (Arkansas, California, New Jersey, Oregon, and South Dakota) are using the facilitated SNAP enrollment strategy. Given that analysis has shown that facilitated enrollment strategies contribute to success enrolling newly eligible adults and children and reducing administrative costs,4 other states may consider adopting the SNAP enrollment practice now that it is a permanent state option.

Renewal Processes

Many states eliminated delays in renewals during 2015. When the ACA was initially implemented, states and the federal government focused heavily on implementing streamlined enrollment processes and establishing coordination between Medicaid and Marketplace coverage. As a result, most states were delayed in implementing the new renewal procedures and 36 states took up a temporary option to postpone renewals for existing Medicaid or CHIP enrollees during 2014.5 During 2015, most states caught up on renewals. As of January 2015, 47 states reported that they are up to date in processing Medicaid renewals.

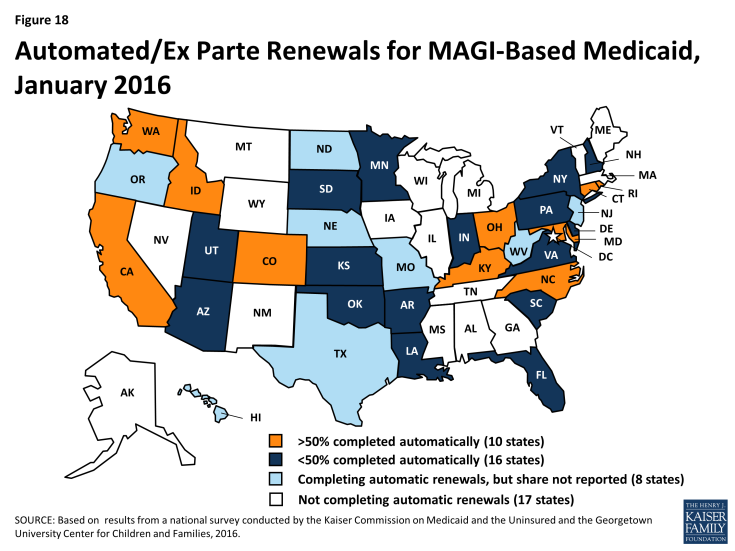

States continued to implement streamlined renewal processes, with 34 states using automated renewal processes as of January 2016, including 10 states that automatically verify ongoing eligibility for more than half of MAGI-based renewals. Similar to data-driven enrollment processes, the ACA requires states to first use available data to determine if ongoing eligibility can be established without requiring the individual to fill out a renewal form or provide paper documentation. As of January 1, 2016, 34 states are using this automated renewal process—known as ex parte. Not all of these states were able to report the share of renewals that are automatically renewed through this process. However, among the 26 states that did report this data, 10 states reported that they are successfully renewing more than 50% of enrollees automatically, with 3 achieving automatic renewals rates above 75% (Figure 18). Under ACA policies, if a renewal cannot be completed automatically based on data, states must send the enrollee a pre-populated notice or renewal form. As of January 2016, 41 states report they are able to send forms or notices that are pre-populated with information (beyond demographics), and 14 states use updated sources of data to populate the form. As is the case with enrollment, the ACA also requires states to provide individuals the option to renew their coverage by telephone. As of January 2016, 41 states provide this renewal option.

States continue to use other policy tools to boost retention.

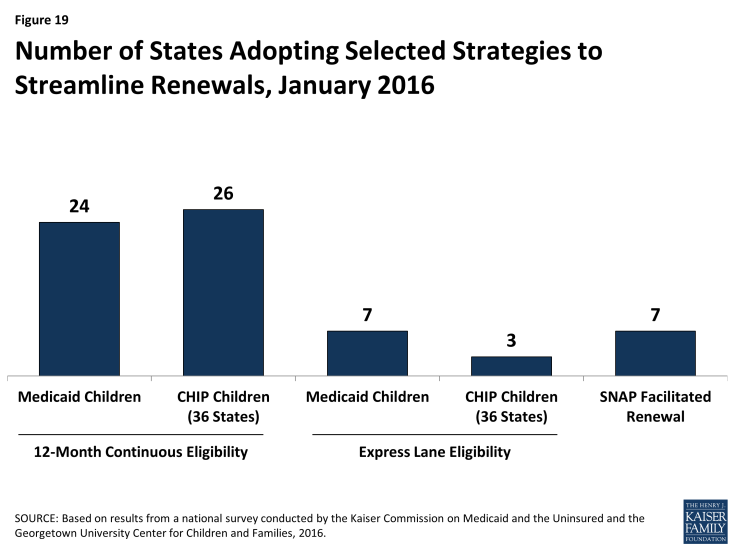

- 12-month continuous eligibility. The ACA established a new policy that requires states to renew coverage no more frequently than once every 12 months. However, enrollees still are required to report changes and will lose coverage if these changes make them ineligible. One way states can provide more stable coverage over time is to provide 12-month continuous eligibility, which provides a full year of coverage regardless of changes in income or household size. This policy promotes retention and improves the ability of states to measure quality. It also reduces the number of people moving on and off of coverage due to small changes in income and lowers state administrative costs that result from processing small changes in income. States have an option to adopt 12-month continuous eligibility for children, but must obtain a waiver to provide it to other groups. As of January 2016, 24 states provide 12-month continuous eligibility to children in Medicaid, while 26 of 36 states with a separate CHIP program have adopted the policy, including Arkansas for its newly established separate CHIP program (Figure 19). In addition, as of January 2016, New York and Montana provide 12-month continuous eligibility to parents and other adults under Section 1115 waiver authority.

- Express Lane Eligibility and Facilitated Renewal Using SNAP data. As is the case at enrollment, states can use ELE to streamline renewals. With the addition of Colorado, as of January 2016, 7 states (Alabama, Colorado, Iowa, Louisiana, Massachusetts, New York, and South Carolina) use ELE at renewal for children in Medicaid, and 3 of the 36 states with separate CHIP programs (Colorado, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania) use ELE for CHIP renewals. In addition, Massachusetts uses ELE to renew parents and other adults in Medicaid under Section 1115 waiver authority. The new option or waiver to use SNAP data to expedite enrollment of eligible individuals also applies to using SNAP data to renew coverage for enrollees. As of January 2016, seven states (Alaska, Arkansas, New Jersey, Oregon, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Virginia) are using SNAP data to renew Medicaid coverage under the waiver or option.