Serious Illness in Late Life: The Public’s Views and Experiences

Section 3: Documenting and Talking About Wishes

As people live longer with more chronic conditions, the potential for more serious health needs increases and people may experience many years of worsening health, including longer periods of time with significant physical or mental functional limitations. One way to help family members and medical providers honor and respect a person’s desires and choices about how they would like to live and be treated in the event they become seriously ill is to have a written document, no matter what age, that describes their wishes and expectations for care, such as the types of treatments they may or may not want, as well as who they would like to make decisions for them if they are no longer able to make decisions on their own. A document outlining a person’s preferences for medical care can have a variety of different names, such as a living will, an advanced treatment directive, a do-not-resuscitate order (DNR), or physician orders for life-sustaining treatment. Other documents may name a person to make decisions about medical care on another person’s behalf, a designation that is sometimes called a health care proxy or surrogate or a durable power of attorney. Throughout this report, these two types of documents will generally be referred to as a document describing a person’s medical wishes and a document naming who would make decisions on another’s behalf.

Nearly All Say Written Documents Are Important and Should Be Done Early in Adulthood

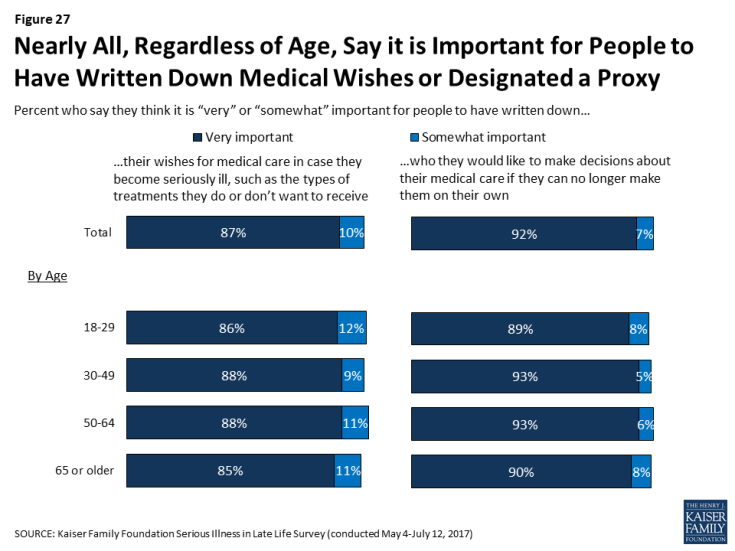

Nearly all adults, regardless of age, say it is important for people to have written down their wishes for medical care or who they would like to make decisions about their medical care in case they become seriously ill.

Figure 27: Nearly All, Regardless of Age, Say it is Important for People to Have Written Down Medical Wishes or Designated a Proxy

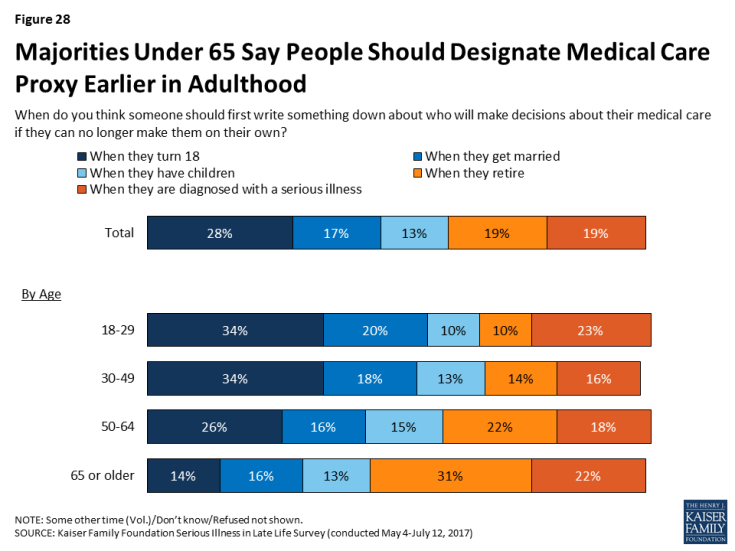

When asked when a person should first write something down about who will make decisions about their medical care if they’re no longer able to make them on their own, the most common answer is when they turn 18 (28 percent), followed by when they retire (19 percent), when they are diagnosed with a serious illness (19 percent), when they get married (17 percent), and when they have children (13 percent). Older adults more commonly say that people should write down who they want to make decisions for them when they retire, while younger people more commonly say it should be done when they turn 18.

Focus Group Insights: Participants felt that planning for serious illness is important to do before someone becomes sick. They noted that conversations during illness were often challenging, wrought with emotion and difficult trade-offs, or came too late.

“We made some decisions that I regret. But we did it not knowing what his real wishes would have been. He wasn’t capable of telling us at that point.”

But, Fewer People Report Actually Having Written Documents

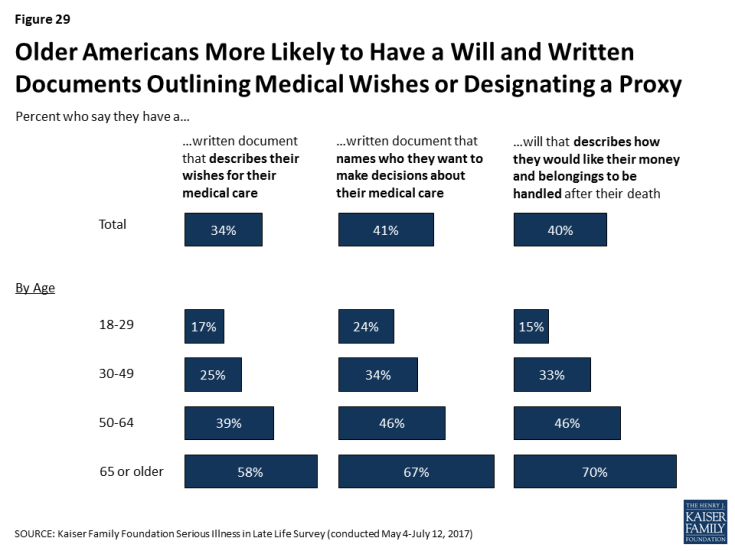

While nearly all say it’s important to have written documents, just a third of the public (34 percent) say they have a written document that describes their wishes for medical care if they became seriously ill, such as the types of treatments they would or would not want to receive. Slightly more (41 percent) report having a document that designates who they would want to make decisions about medical care on their behalf. In addition, for comparison, a similar share (40 percent) say they have a will that documents how they would like their money and belongings handled after their death. Perhaps not surprisingly, those who are older are much more likely to say they have these documents than younger people. For example, two-thirds of those 65 or older say they have a written document designating a proxy, while just a quarter of those 18 to 29 years old say they do (24 percent).

Figure 29: Older Americans More Likely to Have a Will and Written Documents Outlining Medical Wishes or Designating a Proxy

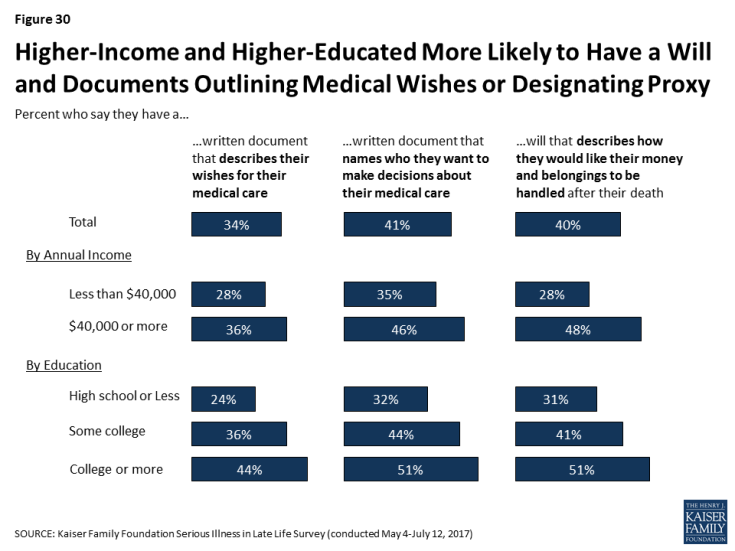

Those with lower levels of income or education are significantly less likely to report having these types of documents. For example, about a third of adults with a high school education or less (32 percent) say they have a document naming a person they would like to make decisions about their medical care, compared to 44 percent of those with some college education and 51 percent of those with at least a college education.

Figure 30: Higher-Income and Higher-Educated More Likely to Have a Will and Documents Outlining Medical Wishes or Designating Proxy

Whether a person is seriously ill or knows someone who is appears to play a limited role in whether or not they have these types of documents. Despite their poor health status, older adults who are themselves dealing with serious illness are somewhat less likely than their peers who are 65 or older to report having such documents. While this may seem counter to the expectation that those in poor health would be more likely to have these documents, this finding is related to the fact that those personally dealing with serious illness themselves report lower levels of education and income which, as noted above, are both factors that make someone less likely to have these types of documents. In addition, those who have a loved one who recently died after a period of serious illness are somewhat more likely than those with no such experience to say they have these documents.

| Table 1: Reports of Planning for Serious Illness by Experience with Illness and Discussion of Death | ||||||||

| Older adults (65+) with serious illness | Older adults (65+) without serious illness | Recent experience with serious illness of a family member | Has a family member or close friend who has died after a period of serious illness | Talked about death growing up |

||||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Occasionally/ Fairly often |

Never/ rarely |

|||

| Percent who say they have a written document that… | ||||||||

| …describes their wishes for medical care | 44% | 59% | 39% | 32% | 37% | 25% | 37% | 30% |

| …names who they want to make decisions about their medical care | 56 | 68 | 47 | 40 | 44 | 35 | 45 | 38 |

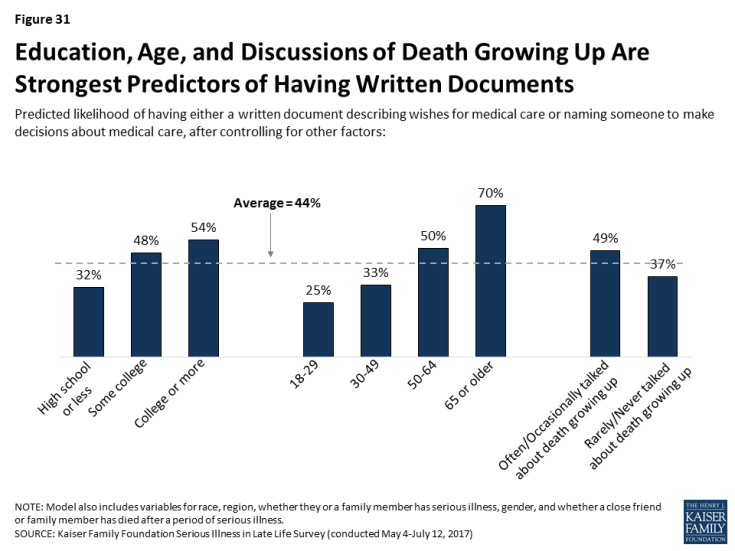

Because many of the factors that can influence whether someone has these types of written documents are inter-related, we conducted a regression analysis to isolate which factors are the strongest predictors of who reports having either type of document. This analysis found that age is the biggest factor in having these types of documents. In addition, those with higher levels of education and those who report that their family talked about death at least occasionally when they were growing up, were more likely to report having either of these documents, even after controlling for factors such as race/ethnicity, personally being seriously ill or knowing someone who has died after a period of illness, region, and gender.

Figure 31: Education, Age, and Discussions of Death Growing Up Are Strongest Predictors of Having Written Documents

Assistance In Writing Documents

Among those who have documents either describing their wishes for care or designating a medical proxy, most say someone helped them prepare the documents. Most often people say it was a lawyer who helped them, and notably very few report getting help from a doctor or nurse or a staff member at a hospital or clinic. About a third of those who have such documents (roughly one in ten of the public overall) say they wrote them on their own.

| Table 2: Most With Documents Say Someone Helped Them | ||

| Percent who say they… | Document describing wishes | Document designating proxy |

| Have a written document | 34% | 41% |

| Someone helped write document | 21% | 25% |

| Lawyer helped | 13% | 15% |

| Family member helped | 4% | 5% |

| Staff member at a hospital or clinic helped | 1% | 2% |

| Doctor/Nurse helped | 1% | 1% |

| Friend helped | 1% | 1% |

| Someone else helped | 1% | 2% |

| Wrote document on their own | 10% | 14% |

| Note: Multiple answers were accepted for who helped. | ||

Creating and Reviewing Documents

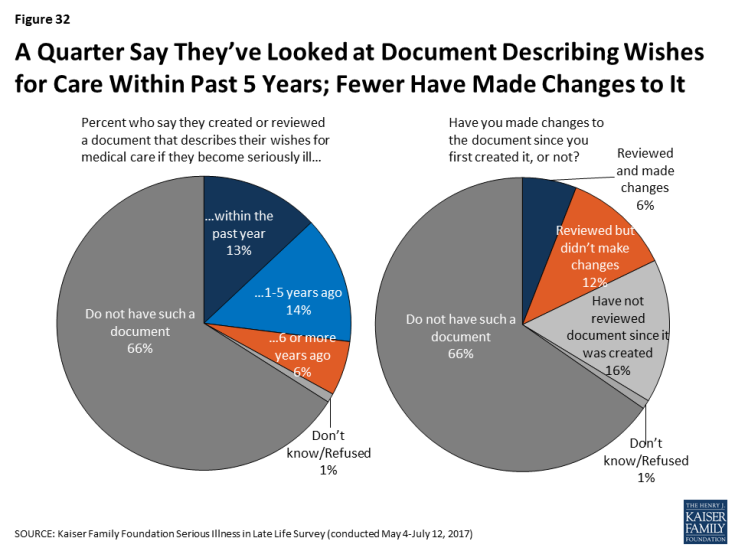

Keeping these documents up to date can help avoid questions and confusion when they are put to use. Most of those who report having such a document, or about a quarter of the public overall (27 percent), say they first created or have reviewed the document within the past five years, including 13 percent who say they created or reviewed the document within the past year. Just 6 percent of the public say they have a document and they’ve made changes to the document since they first created it.

Figure 32: A Quarter Say They’ve Looked at Document Describing Wishes for Care Within Past 5 Years; Fewer Have Made Changes to It

Sharing Documents with Others

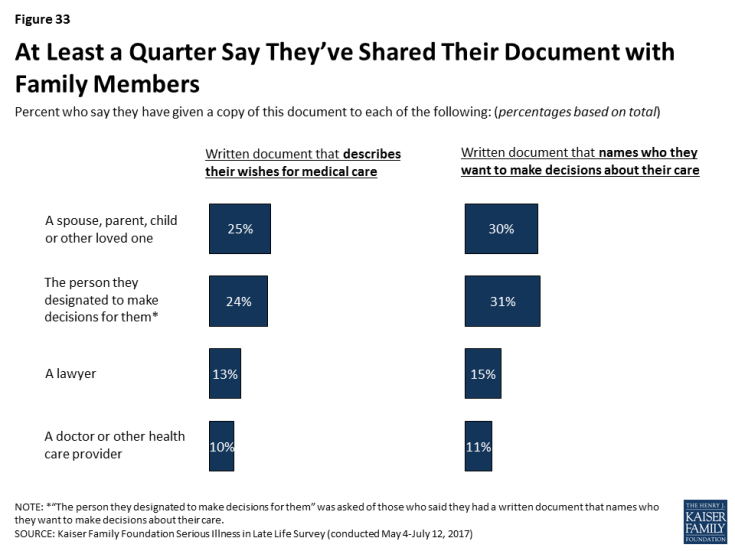

These types of documents can be more useful in helping loved ones and medical providers follow a person’s wishes if others know they exist and where to find them. Large majorities of those with a document (between a quarter and three in ten of the public overall) say they’ve given it to a spouse, parent, child, or other loved one, or that they’ve specifically given it to the person designated to make decisions for them. However, relatively few say they have given the document to a lawyer, and perhaps most importantly, just about three in ten of those with these types of documents (one in ten of the public overall) say they have given them to a doctor or other health care provider.

Barriers to Written Documents Outlining Wishes

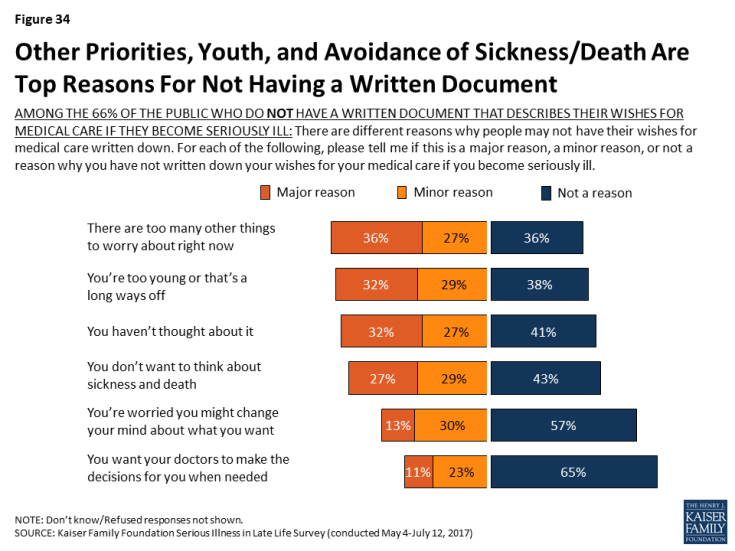

For the 66 percent of the public that report not having a written document that outlines their wishes for medical care if they become seriously ill, many say that a number of barriers stand in their way, such as having too many other things to worry about right now (63 percent), feeling too young or that it’s a long way off (61 percent), they haven’t thought about it (58 percent), or that they don’t want to think about sickness and death (56 percent). Younger people are more likely than older people to say most of these are reasons they don’t have a written document outlining their wishes.

Figure 34: Other Priorities, Youth, and Avoidance of Sickness/Death Are Top Reasons For Not Having a Written Document

| Table 3: Barriers to Written Documents Outlining Wishes Varies by Age | |||||

| AMONG THE 66% OF THE PUBLIC WHO DO NOT HAVE A WRITTEN DOCUMENT THAT DESCRIBES THEIR WISHES FOR MEDICAL CARE IF THEY BECOME SERIOUSLY ILL: Percent who say each of the following was a major or minor reason why they have not written down their wishes for medical care if they become seriously ill: | Total | Age | |||

| 18-29 | 30-49 | 50-64 | 65+ | ||

| There are too many other things to worry about right now | 63% | 71% | 65% | 58% | 50% |

| You’re too young or that’s a long ways off | 61 | 80 | 66 | 49 | 34 |

| You haven’t thought about it | 58 | 61 | 66 | 51 | 47 |

| You don’t want to think about sickness and death | 56 | 56 | 60 | 60 | 41 |

| You’re worried you might change your mind about what you want | 42 | 48 | 45 | 37 | 33 |

| You want your doctors to make the decisions for you when needed | 34 | 37 | 35 | 30 | 31 |

Focus Group Insights: Barriers to planning and writing down wishes include a societal taboo of discussing death, fear of death, and procrastination.

“I’m not ready to die, I think I’m too young.”

“Nobody wants to be faced with their own mortality.”

“I’ll deal with it tomorrow. The perpetual tomorrow”

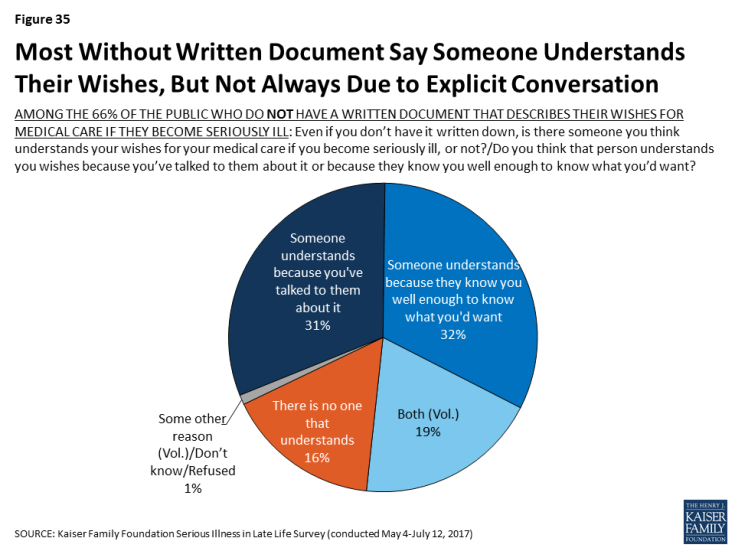

Perhaps another barrier that prevents people from creating documents outlining their wishes for medical care is the feeling that someone else already understands what they would want. More than eight in ten of those who don’t have a written document describing their medical wishes say they think there is someone who understands their wishes. However, some (32 percent of those without a written document) say they think that someone else knows their wishes because they know them well enough to know what they’d want, rather than because they’ve talked to them about it (31 percent).

Figure 35: Most Without Written Document Say Someone Understands Their Wishes, But Not Always Due to Explicit Conversation

However, Many say they’ve talked about these things with their family

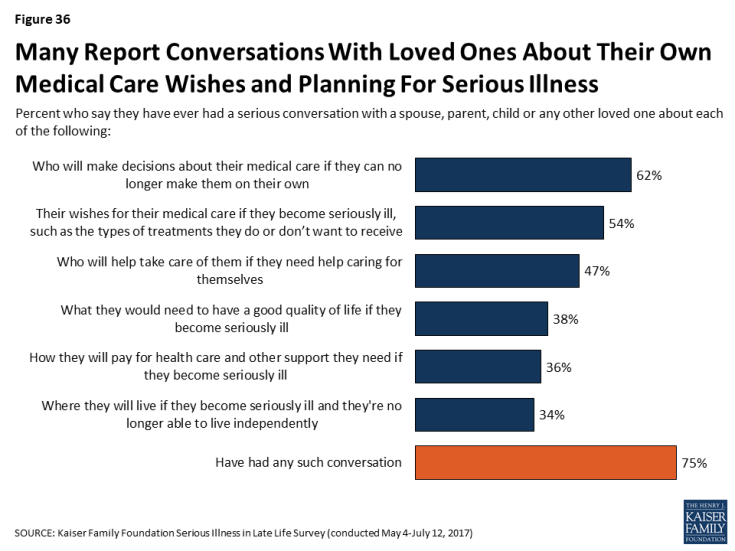

Although most of the public says they don’t have a document outlining their wishes or who they would want to make decisions for them if they were to become seriously ill, many do say they have had a serious conversation with a spouse, parent, child, or other loved one about a number of different aspects of planning for potentially becoming seriously ill. More than half say they’ve had a serious conversation with a loved one about who will make medical decisions if they can no longer do so on their own (62 percent) or about their wishes for medical care if they become serious ill (54 percent). About half say they have talked with a loved one about who would help take care of them if they needed help caring for themselves (47 percent). Less frequently reported types of conversations include what they would need to have a good quality of life while seriously ill (38 percent), how they would pay for health care and other support they might need if seriously ill (36 percent), and where they would live if they’re no longer able to live independently (34 percent). However, many still say they have not had discussions about some of the specific topics experts say are important parts of planning for serious illness.

It’s particularly notable that one of the types of conversations that is less often reported is about finances, the aspect that may take the most advanced planning and one that ties into several of the other aspects such as access to housing and support services.

Figure 36: Many Report Conversations With Loved Ones About Their Own Medical Care Wishes and Planning For Serious Illness

Generally, older people are more likely than younger adults to report having these types of conversations with loved ones. Those who are 65 or older who themselves are dealing with serious illness are no more likely than their peers in better health to say they’ve had these types of conversations with a family member.

| Table 4: Serious Conversations with a Family Member About Planning for Serious Illness, by Age | ||||||

| Percent who say they have ever had a serious conversation with a spouse, parent, child or any other loved one about each of the following: | By Age | Serious Illness | ||||

| 18-29 | 30-49 | 50-64 | 65+ | Older adults (65+) with serious illness | Older adults (65+) without serious illness | |

| Who will make decisions about their medical care if they can no longer make them on their own | 40% | 59% | 69% | 82% | 80% | 83% |

| Their wishes for medical care if seriously ill | 38 | 46 | 61 | 71 | 70 | 71 |

| Who will help take care of them if they need help caring for themselves | 31 | 40 | 55 | 65 | 66 | 65 |

| What’s needed for a good quality of life if seriously ill | 25 | 35 | 43 | 48 | 44 | 48 |

| Where they’ll live if seriously ill | 17 | 29 | 39 | 55 | 54 | 55 |

| How to pay for health care and other support if seriously ill | 22 | 32 | 43 | 47 | 38 | 48 |

| Yes to any of the above types of conversations | 59 | 71 | 80 | 90 | 92 | 90 |

But, those who have some connection to serious illness, either with a loved one currently facing illness or knowing someone who died after a period of illness are more likely to say they’ve talked about some of these things. For example, 58 percent of those who say they have a family member or close friend that died after a period of serious illness say they have discussed their wishes for medical care if they become seriously ill with a family member, compared to 43 percent of other adults. In addition, those who say their family talked about death at least occasionally when they were growing up are more likely to report having at least one of these types of conversations with family members than those who report talking about death less frequently.

| Table 5: Serious Conversations with a Family Member About Planning for Serious Illness, by Experience with Illness | ||||||

| Percent who say they have ever had a serious conversation with a spouse, parent, child or any other loved one about each of the following: | Recent experience with serious illness of a family member | Has a family member or close friend who has died after a period of serious illness | Talked about death growing up | |||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Occasionally/ Fairly Often |

Rarely/never | |

| Who will make decisions about their medical care if they can no longer make them on their own | 68% | 61% | 66% | 54% | 65% | 59% |

| Their wishes for medical care if seriously ill | 56 | 53 | 58 | 43 | 57 | 50 |

| Who will help take care of them if they need help caring for themselves | 54 | 46 | 50 | 41 | 51 | 43 |

| What’s needed for a good quality of life if seriously ill | 42 | 37 | 41 | 30 | 43 | 32 |

| Where they’ll live if seriously ill | 41 | 33 | 38 | 26 | 37 | 31 |

| How to pay for health care and other support if seriously ill | 42 | 35 | 39 | 29 | 40 | 31 |

| Yes to any of the above types of conversations | 79 | 74 | 79 | 66 | 80 | 69 |

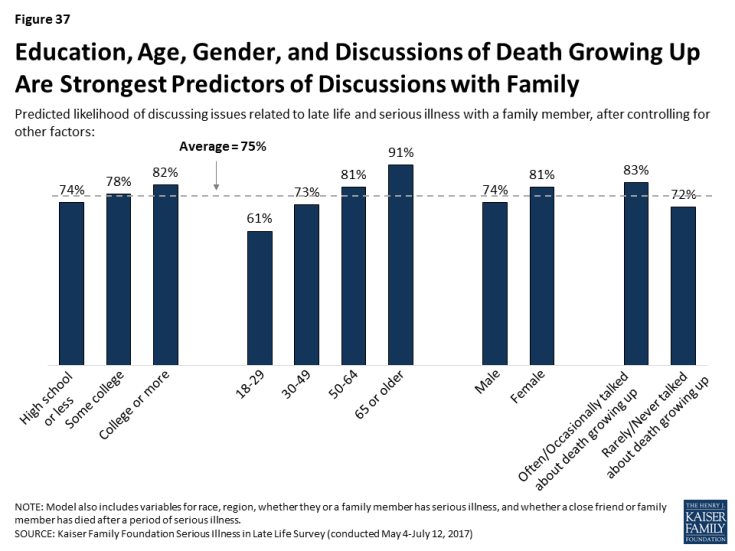

A regression analysis shows that the factors most associated with discussing these issues with family members, are higher levels of education, being older, being female, and having discussed death with family growing up at least occasionally, even after controlling for race/ethnicity, region, knowing someone who has died after a period of serious illness, and being personally seriously ill. Age is the most influential factor, even after considering other personal characteristics.

Figure 37: Education, Age, Gender, and Discussions of Death Growing Up Are Strongest Predictors of Discussions with Family

Most Say They Have Discussed These Issues With Their Family More Than Once

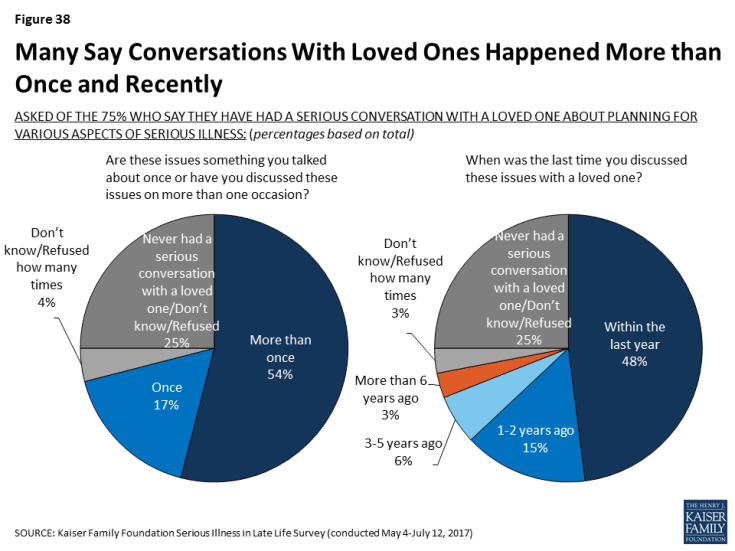

People who report having conversations with family members about preparations for serious illness say they’ve had such conversations repeatedly, and recently. Experts consider both to be an important part of planning for serious illness because wishes may change with time or as circumstances change. About half of the public say they’ve discussed these issues with loved ones more than once, while 17 percent say they’ve only discussed them once. Most of those who report talking with their family about these issues say they’ve discussed them within the past year (48 percent of the public overall), particularly those who say their health is fair or poor (59 percent).

Relatively Few Say They Have Talked About Preparing for Serious Illness with Medical Providers, Lawyers, Financial planners, or Religious Leaders

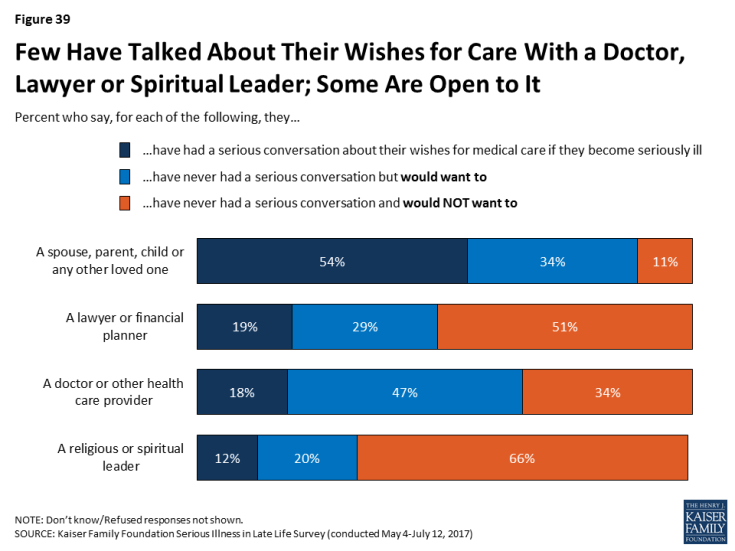

Doctors and other medical providers can play an important role in helping people fulfill their wishes for medical care if they become seriously ill, however relatively few say they’ve talked to a medical provider about who would make decisions for them (23 percent), what sort of medical care they would want (18 percent), or where they would like to receive care if they became seriously ill (11 percent). Older people and people in fair or poor health are more likely to report having these types of conversations with a doctor, but still just about half of older people say they’ve talked about any of these issues.

| Table 6: Serious Conversations with Doctors or Other Health Care Providers about Planning for Serious Illness, By Age and Health Status | |||||||

| Percent who say they have ever had a serious conversation with a doctor or other health care provider about each of the following: | Total | Age | Health Status | ||||

| 18-29 | 30-49 | 50-64 | 65+ | Excellent/Very good/Good | Fair/Poor | ||

| Who will make decisions about their medical care if they can no longer make them on their own | 23% | 18% | 19% | 23% | 37% | 22% | 30% |

| Their wishes for medical care if seriously ill | 18 | 9 | 11 | 19 | 34 | 16 | 24 |

| Where they would like to receive care if seriously ill | 11 | 8 | 9 | 11 | 20 | 10 | 17 |

| Yes to any of the above types of conversations | 31 | 24 | 23 | 30 | 51 | 28 | 41 |

Focus Group Insights: There are mixed reactions to how involved physicians should be in the planning process. Some people say they are resistant to talking with their doctors about planning for serious illness because they don’t want to think about dying while they’re at the doctors’. Others say they would prefer to get information from doctors that they can take home and consider, while others are open to conversations with providers they know well.

“Every time I go, [a doctor asks] do you have a do-not-resuscitate? And it makes me feel funny because I’m at the doctors and I don’t want to think about dying right now, thank you very much.

There are other individuals that can play a role in helping to shape or fulfill an individual’s wishes for medical care if they become seriously ill, such as a lawyer or financial planner who can help create legal documents or savings plans and religious or spiritual leaders who can help individuals outline what’s important to them in sickness and dying. But conversations with these individuals about wishes for medical care are also relatively rare – 19 percent say they’ve talked with a lawyer or financial planner and 12 percent say they’ve talked with a religious or spiritual leader.

For those who haven’t had these types of conversations with their family, medical providers, lawyers or financial planners, or religious leaders, some say they would want to do so. For example, for the 46 percent who say they haven’t talked with a family member about their wishes for medical care if they become seriously ill, most say they would want to (34 percent of the public overall). Notably, half the public (51 percent) say they have not and do not want to discuss these issues with a lawyer or financial planner, and two-thirds (66 percent) say the same about discussions with a religious or spiritual leader.

Figure 39: Few Have Talked About Their Wishes for Care With a Doctor, Lawyer or Spiritual Leader; Some Are Open to It

Reports of Planning Among Family Members of Older Adults with Serious Illness

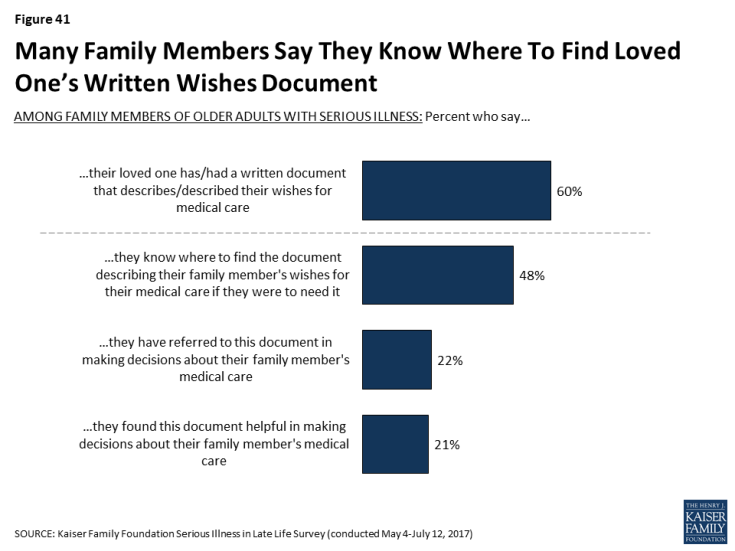

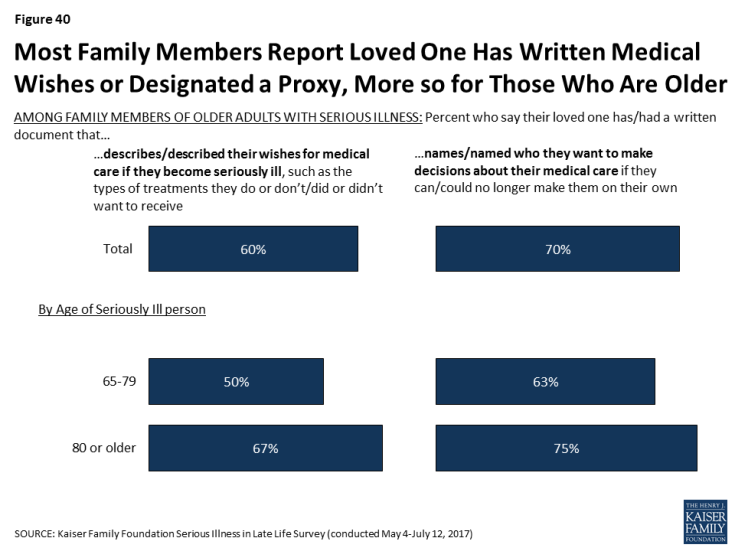

Among family members of older adults with serious illness, most report that their loved one has a document that describes their wishes for medical care (60 percent) or designates someone to make medical decisions on their behalf (70 percent). Those whose loved one is at least 80 years old are more likely than those whose family members are between ages 65-79 to say they have these written documents.

Figure 40: Most Family Members Report Loved One Has Written Medical Wishes or Designated a Proxy, More so for Those Who Are Older

Family members, for the most part, say that if their loved one has a document describing their wishes for medical care, they know where to find it if they were to need it (80 percent of those whose family member has a written document, or 48 percent of all family members of older adults with serious illness). About one in five say they have referred to this document when making decisions about their family member’s care and nearly all of those who referred to the document say it was helpful to have (21 percent of family members overall).

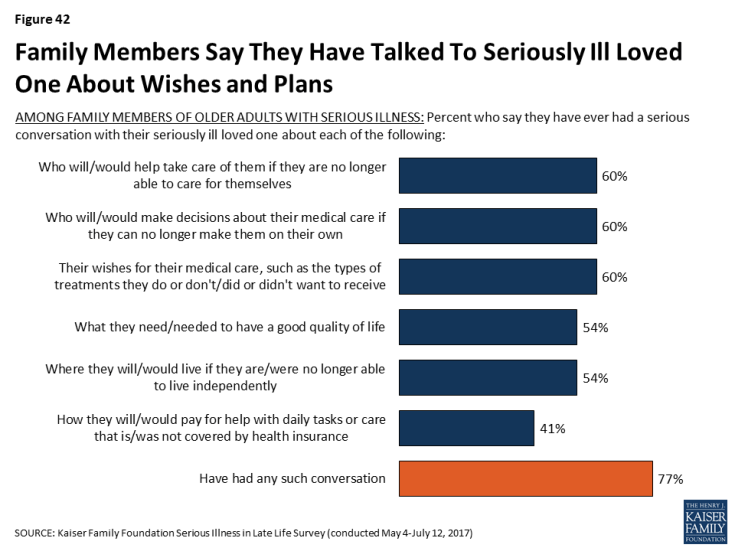

A majority of family members of older people with serious illness say that they have had a serious conversation about a variety of aspects of planning for late life and poor health. Six in ten family members say they’ve talked with their loved one about their wishes for medical care (60 percent), who would make decisions for them about their medical care if they were no longer able to make them on their own (60 percent), or who would help take care of them if they were no longer able to care for themselves (60 percent). Over half say they’ve talked with their family member about what they need to have a good quality of life while sick and where they would like to live if they can’t live independently (54 percent each). A smaller share, about four in ten, say they’ve talked to their family member about how they will pay for help with daily tasks or care that isn’t covered by health insurance (41 percent). It’s notable that here family members are also reporting their loved ones are talking less about finances than about some of their other expectations about late life and serious illness. Of course, family members are answering about their conversations with their loved one and it’s possible their loved one has had a conversation with a different family member.

Focus Group Insights: Family members of those with serious illness say that staying at home is an attractive option until the reality of the level of care needed becomes apparent.

“She would have stayed at home all the way. She had always said, ‘Don’t ever put me anywhere. I want to always be at home.’ We’d always agreed to that until we were in that position. I never thought I would put her anywhere else, ever.”

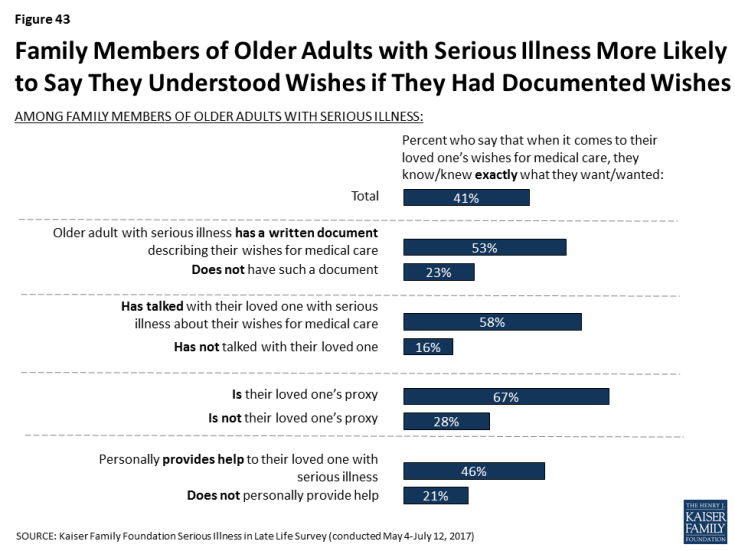

Understanding And Following Loved Ones Wishes

Most family members of older adults with serious illness say they know or knew exactly what their loved one’s wishes for medical care are or that they have a pretty good idea. And, for those that say they don’t really know their loved one’s wishes, eight in ten (83 percent) say that there’s another family member that knows their wishes better than they do. Writing wishes down and talking about them appears to make a big difference; family members whose loved one has a written document outlining their wishes are more than twice as likely to say they know exactly what their loved one wanted than those without such a document (53 percent versus 23 percent). And, family members who say they talked with their seriously ill loved one about their wishes are more than three times as likely than others to say they know exactly what their loved one wanted (58 percent vs. 16 percent). Those family members that are designated as their loved one’s proxy or help their loved one with daily activities or other types of assistance are also more likely to say they know exactly what their seriously ill loved one wants for their medical care.

Figure 43: Family Members of Older Adults with Serious Illness More Likely to Say They Understood Wishes if They Had Documented Wishes

Focus Group Insights: Family members of those with serious illness appreciate when wishes are known and steps are taken to plan for serious illness. They expressed frustration when decision making is left up to them.

“She had living will and power of attorney but you know what it said? Unless it was putting her in a facility or she was on life support, in other words other than two options, it was up to us to decide. I’m like, ‘That’s not an answer.’ I think she’s one of those, if you avoid this subject then it’s not going to happen. That was very frustrating.”

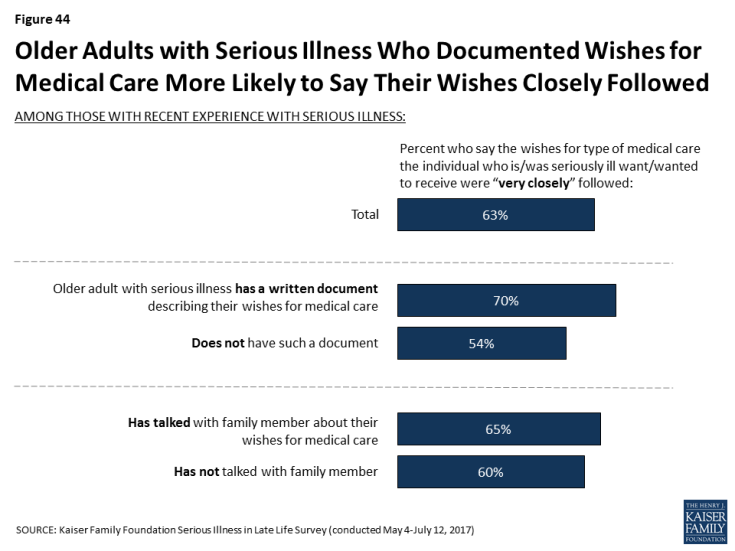

Among individuals and family members of older adults with serious illness, nearly all say their or their loved ones wishes for their medical care are being very or somewhat closely followed, including more than six in ten who say they are ‘very closely’ followed. Those who say they have documents outlining their wishes are more likely to say their wishes are ‘very closely’ followed than those that do not (70 percent versus 54 percent), but there’s no difference for those who say they’ve talked about them compared to those who say they haven’t discussed their wishes (65 percent and 60 percent). However, as noted above, those family members who haven’t talked with their loved one about their wishes are less familiar with the care they want and therefore may not be able to accurately describe if their wishes for care are being closely followed.

Figure 44: Older Adults with Serious Illness Who Documented Wishes for Medical Care More Likely to Say Their Wishes Closely Followed

Most family members of older adults with serious illness (68 percent) say there are rarely or never disagreements among family members about what sort of medical care their loved one should or shouldn’t receive, but about one in ten (9 percent) say there are often disagreements, and about two in ten (22 percent) say there are sometimes disagreements. Those who say their family member has had conversations with them or has a written document about their wishes are no more likely to say there are frequently disagreements among family members.

Planning: Financial Preparations

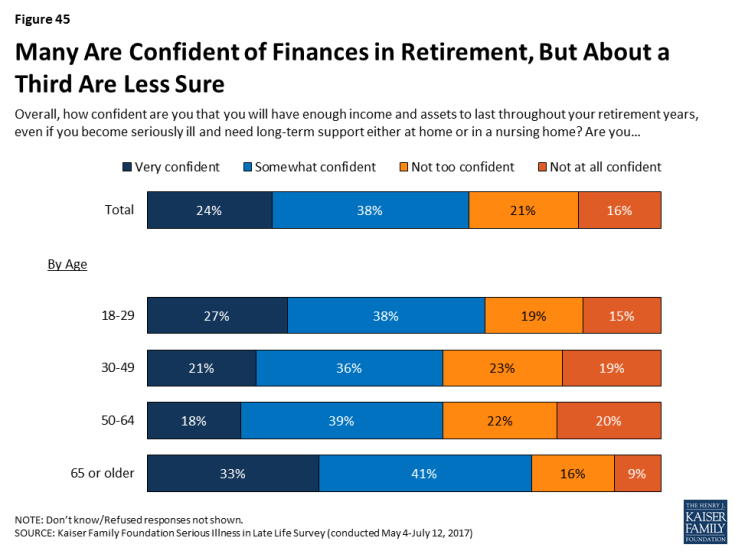

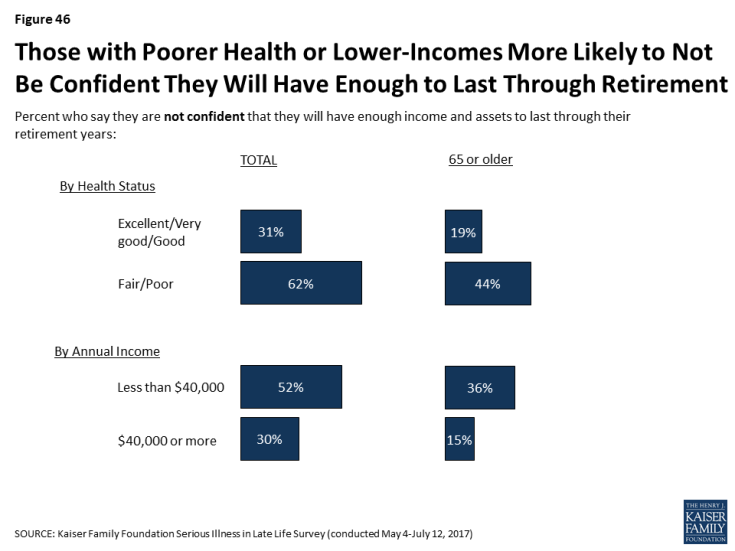

As noted above, just 36 percent of the public say they have personally had a serious conversation with a loved one about how they would pay for medical care and other needed services if they become seriously ill. While they may not be talking about this issue, about six in ten of the public say they feel very or somewhat confident they will have enough income and assets to last throughout their retirement years, even if they become seriously ill and need long-term support either at home or in a nursing home, but 37 percent are not confident they will. For those currently in or near their retirement years – those 65 or older – 74 percent feel confident they have enough income and assets for retirement, even if they become sick. And, for many older adults, this confidence may not be misplaced; more than six in ten of adults 65 or older are estimated to be financially secure, however this security declines for the oldest adults (75 or older), and still many are estimated to have more tenuous financial circumstances.1

A striking 62 percent of those in fair or poor health and 52 percent of those making less than $40,000 annually say they’re not confident they’ll have enough income and assets to last through retirement. Looking specifically at those age 65 or older, roughly four in ten of those in fair or poor health or of those with annual incomes of less than $40,000 say they are not confident they will have enough income and assets to last throughout their retirement.

Figure 46: Those with Poorer Health or Lower-Incomes More Likely to Not Be Confident They Will Have Enough to Last Through Retirement

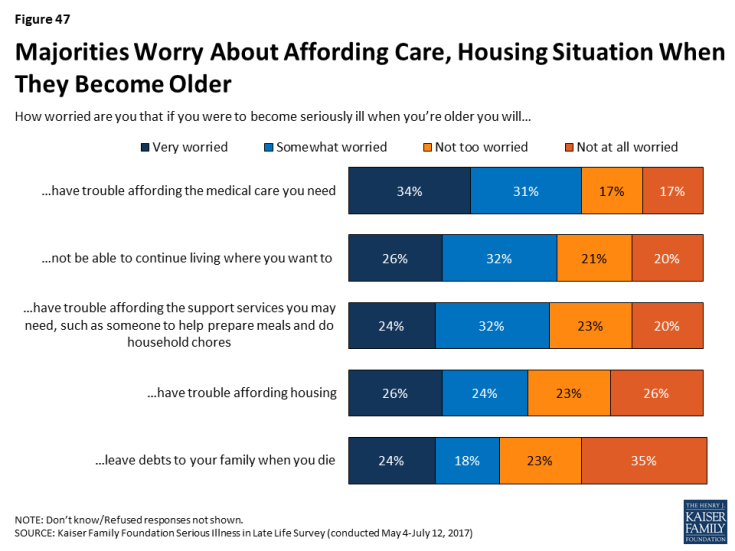

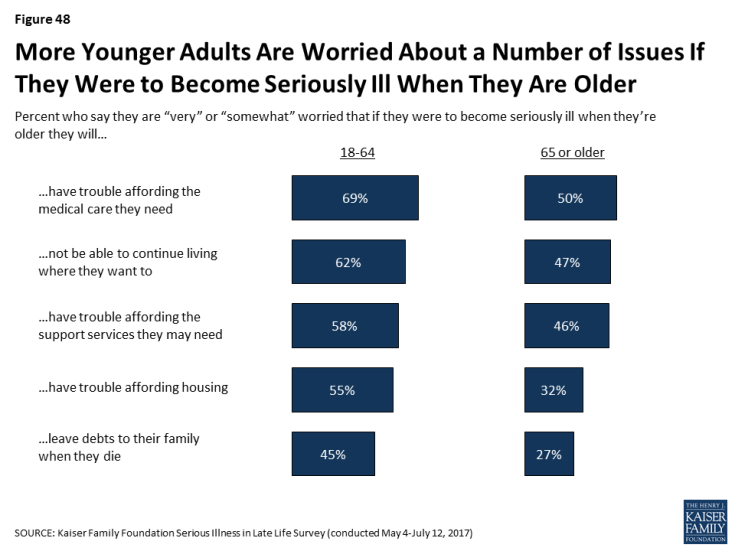

Even while many are confident they will have the income and assets to last through retirement in the event of illness, many say they are worried that if they were to become seriously ill when they are older they will have trouble affording needed medical care (65 percent), not be able to continue living where they want to (59 percent), have trouble affording support services (56 percent), have trouble affording housing (50 percent), or that they will leave debts to their family when they die (42 percent). Younger adults are particularly worried about these issues.

Figure 48: More Younger Adults Are Worried About a Number of Issues If They Were to Become Seriously Ill When They Are Older

Steps Taken to Plan for Aging

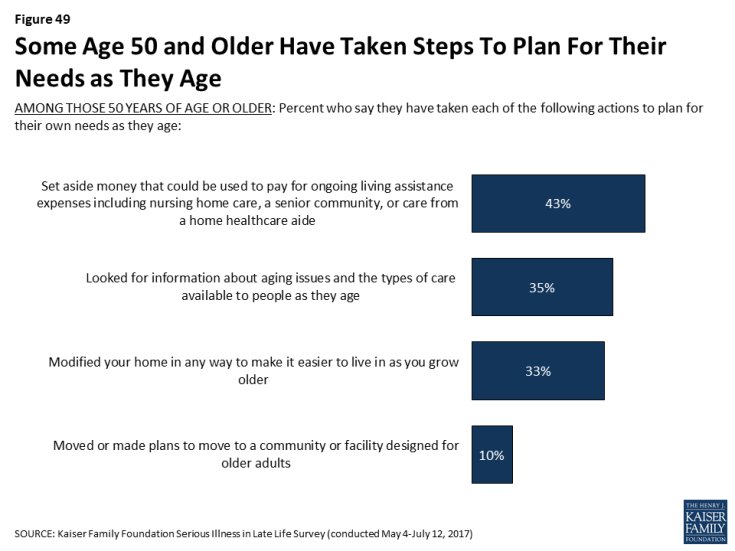

Some people 50 and older report taking a variety of actions to plan for their own needs as they age, such as setting aside money that could be used to pay for ongoing living assistance (43 percent), looking for information about aging issues and the types of care available to people as they age (35 percent), modifying their home to make it easier to live in as they grow older (33 percent), or moving or making plans to move to a place designed for older adults (10 percent).

In addition, about half of those who have not yet retired (53 percent) say they are currently saving for retirement. Adults under 30 are much less likely to say they are saving (39 percent), but majorities of those 30 to 49 (59 percent) and 50-64 (57 percent) say they are, as well as about half (49 percent) of those 65 or older who are not already retired.

| Table 7: Steps Taken to Plan for Serious Illness | ||||

| Age | ||||

| 18-29 | 30-49 | 50-64 | 65+ | |

| AMONG THOSE 50 YEARS OF AGE OR OLDER: Percent who say that in order to plan for their needs as they age they have… | ||||

| …Set aside money that could be used to pay for ongoing living assistance expenses | — | — | 36% | 52% |

| …Looked for information about aging issues and the types of care available to people as they age | — | — | 28 | 43 |

| …Modified your home in any way to make it easier to live in as you grow older | — | — | 28 | 40 |

| …Moved or made plans to move to a community or facility designed for older adults | — | — | 7 | 13 |

| AMONG THOSE WHO ARE NOT RETIRED: Percent who say they are… | ||||

| …Currently saving for retirement | 39 | 59 | 57 | 49 |

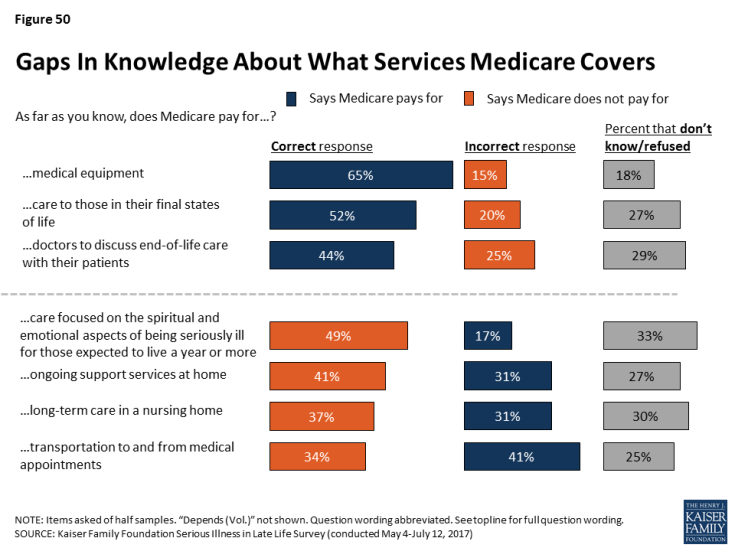

Misconceptions About The Role of Medicare in Late Life

Other surveys have shown that much of the public expects to rely on Medicare when they get older.2 However, there are misconceptions about what Medicare does and does not cover that can leave people ill prepared to handle expenses they have to pay out of pocket. Many are correctly aware that Medicare covers medical equipment, such as wheelchairs and other assistive devices (65 percent), care to those in their final stages of life (52 percent), and doctors’ discussions with patients about end-of-life care (44 percent). However, about three in ten incorrectly say Medicare covers ongoing support services at home, such as someone to help prepare meals and do household chores, or that it covers long-term care in a nursing home. Four in ten incorrectly say it covers transportation to and from medical appointments for those who can no longer drive. About two in ten incorrectly say Medicare covers care that focuses on the spiritual and emotional aspects of living with a serious illness for those who are expected to live a year or more.