Medicare Spending at the End of Life: A Snapshot of Beneficiaries Who Died in 2014 and the Cost of Their Care

What are the characteristics of medicare beneficiaries who died at some point in 2014?

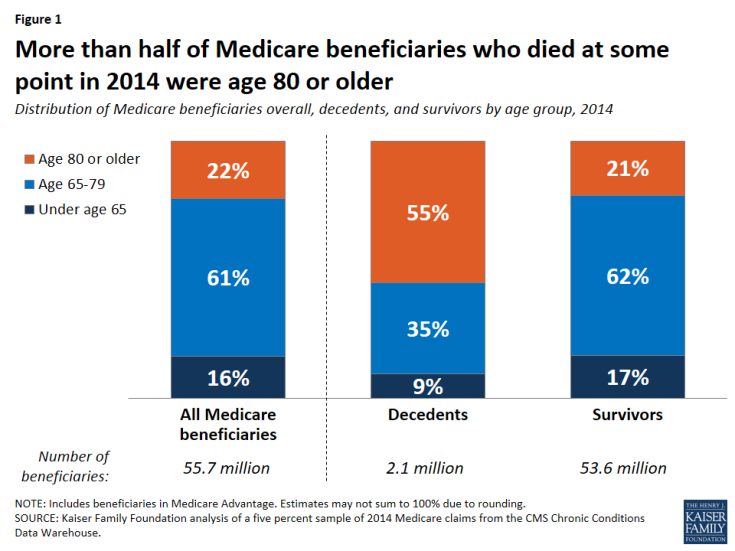

More than half of Medicare decedents were age 80 or older in 2014.

- Of the more than 2.1 million Medicare beneficiaries who died at some point in 2014—representing 4.0% of the total Medicare population that year—over half (55%) were age 80 or older, which is more than double their share of the Medicare population overall (22%) (Figure 1). Just over half (52%) of decedents were women and eight out of 10 were non-Hispanic white (81%), roughly comparable to their shares of the overall Medicare population (54% and 77%, respectively).

- More than seven in 10 (72%, or 1.5 million) Medicare decedents were in traditional Medicare in 2014, and the remainder (28%, or 0.6 million) were enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans, reflecting overall enrollment patterns in traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage.

- Diseases that were highly prevalent among decedents in traditional Medicare in 2014 include hypertension (67%), ischemic heart disease (53%), chronic kidney disease (51%), congestive heart failure (48%), Alzheimer’s disease or dementia (43%), diabetes (38%), and cancer (17%). The prevalence of each of these conditions was higher among beneficiaries who died at some point in 2014 than among beneficiaries overall, in some cases substantially higher (Table 1). For example, more than 4 in 10 decedents had Alzheimer’s or dementia, compared to only 9% of beneficiaries overall, and more half of decedents had ischemic heart disease, compared to one fourth of beneficiaries overall.

How does medicare per capita spending differ for decedents and survivors in 2014 and over time?

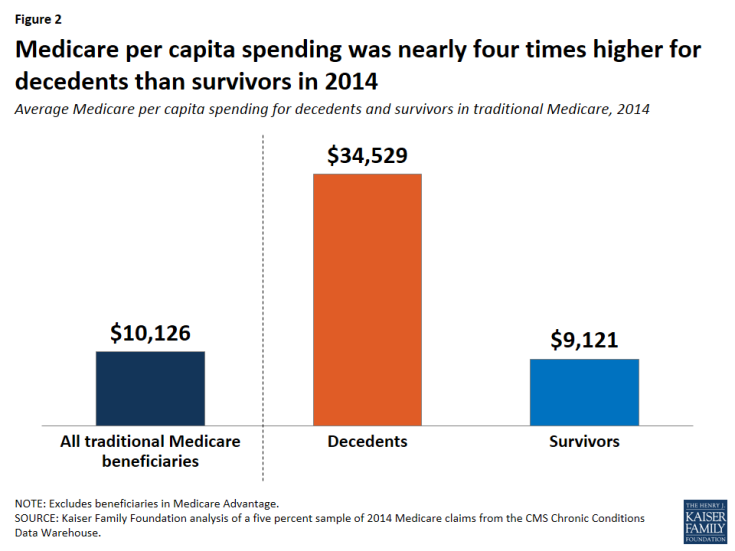

Average total Medicare per capita spending was nearly four times higher for beneficiaries in traditional Medicare who died at some point in 2014 than for those who lived the entire year.

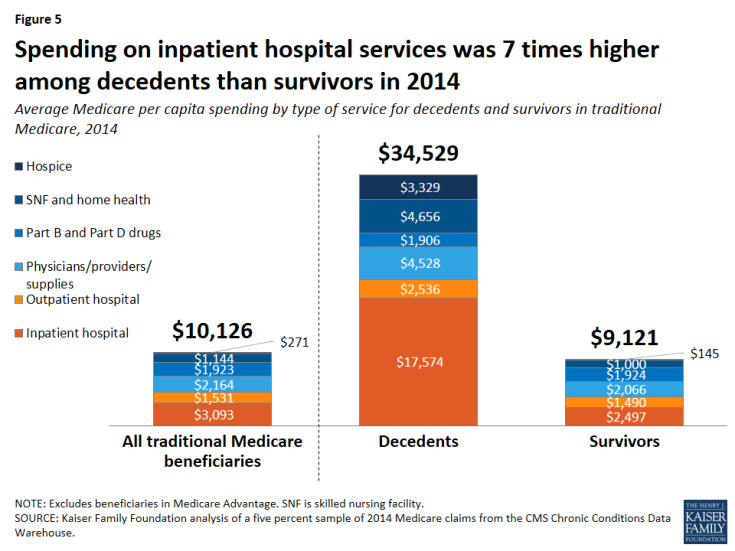

- Average Medicare per capita spending on services covered under Parts A, B, and D for traditional Medicare beneficiaries who died at some point in 2014 was $34,529—nearly four times higher than per capita spending for survivors ($9,121) and more than three times higher than the average among all beneficiaries in traditional Medicare ($10,126) (Figure 2).

- In 2014, beneficiaries who died at some point during the year accounted for 4% of all beneficiaries in traditional Medicare, but 13.5% of traditional Medicare spending. This amount is disproportionate to the decedent share of beneficiaries overall, but it accounts for a relatively small share of total spending that year. This estimate is lower than the 25% estimate cited earlier because it is based on Medicare spending for people who died at some point in a given calendar year (in this case, 2014), rather than the last 12 months of spending for people who died.1

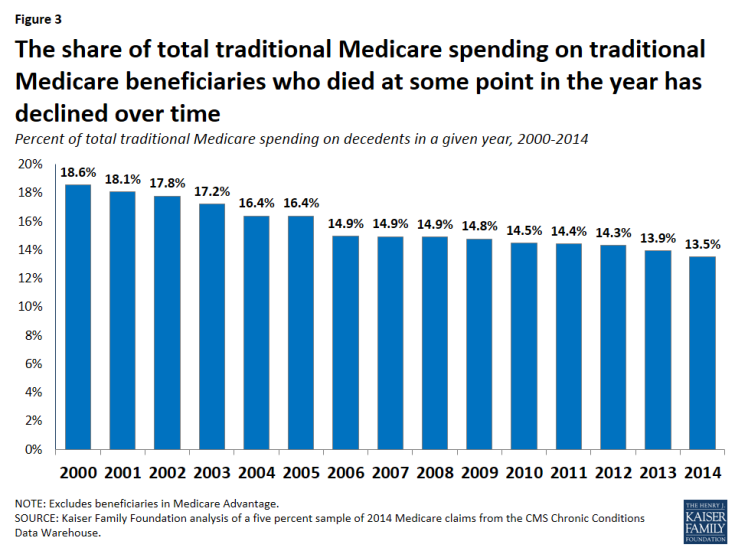

The share of total traditional Medicare spending on beneficiaries who died at some point during the year has decreased over time.

- The share of total traditional Medicare spending on beneficiaries who died at some point during the year has dropped over time, from 18.6% in 2000 to 13.5% in 2014 (Figure 3). This drop is likely due to a combination of factors affecting total traditional Medicare spending over time and spending on decedents, including: growth in the number of Medicare beneficiaries overall, particularly in recent years as the baby boom generation ages on to Medicare, which means more younger, healthier beneficiaries, on average; longer life expectancy, which means people are living longer and dying at older ages (as seen in a decline in the share of traditional Medicare beneficiaries who die at some point in a given year—from 4.9% in 2000 to 4.0% in 2014); lower average per capita spending on older decedents compared to younger decedents (as described further below); and slower growth in the rate of annual per capita spending for decedents than survivors (also described further below).

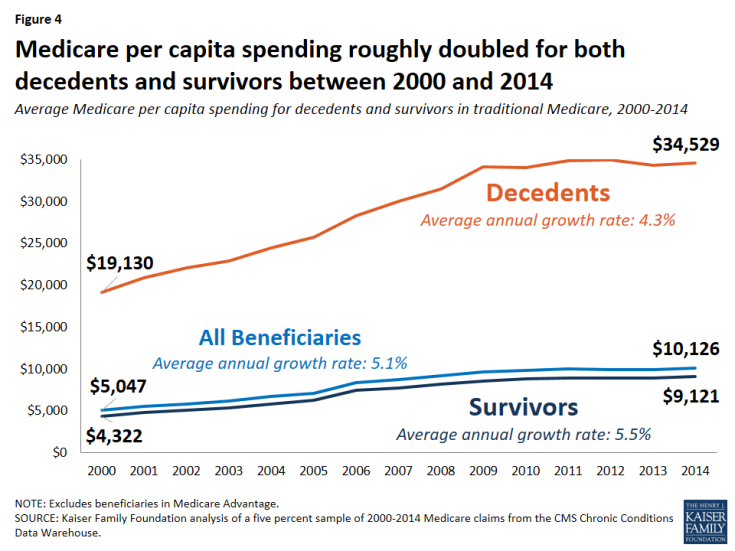

Between 2000 and 2014, the annual rate of growth in average Medicare per capita spending was lower among decedents than survivors.

- Average Medicare spending among decedents was 80% higher per person in 2014 ($34,529) than in 2000 ($19,130), while average spending among survivors more than doubled between 2000 and 2014, from $4322 to $9,121 (Figure 4).

- Although average per capita spending was higher for decedents than survivors in each year between 2000 and 2014, the average annual rate of growth in spending over this time period was lower for decedents (4.3%) than for survivors (5.5%).

What services account for the difference in medicare per capita spending between decedents and survivors?

Higher Medicare per capita spending among decedents than survivors in traditional Medicare is primarily driven by much higher spending on inpatient hospital services.

- Spending on inpatient hospital services accounted for the largest amount of per capita Medicare spending by type of service among decedents in traditional Medicare in 2014 (Figure 5; Table 2), and was the primary reason for the substantial difference in spending between decedents and survivors. Per capita inpatient hospital spending among decedents was $17,574 in 2014, on average, seven times higher than among survivors ($2,497). Decedents also incurred much higher spending on post-acute care (skilled nursing facility (SNF) and home health services) and hospice care than survivors in 2014.

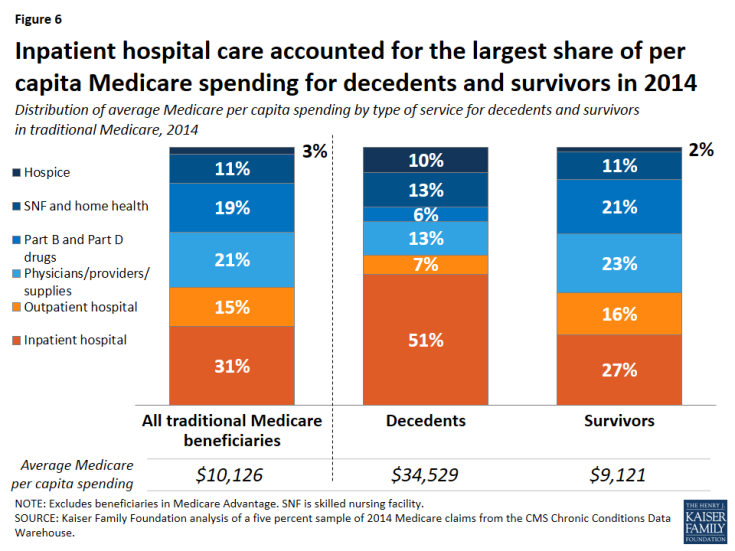

- Inpatient hospital services accounted for the largest share of average Medicare per capita spending by type of service for traditional Medicare beneficiaries overall in 2014 (31%), but the share of per capita spending on inpatient hospital services was particularly large for decedents, accounting for just over half (51%) of total spending in 2014 (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Inpatient hospital care accounted for the largest share of per capita Medicare spending for decedents and survivors in 2014

- For decedents, the next largest service categories were physicians, providers, and supplies combined and post-acute care (skilled nursing facilities and home health services), at 13% each, followed by hospice care (10%). For surviving beneficiaries in traditional Medicare, inpatient hospital services accounted for 27% of total per capita Medicare spending in 2014, followed closely by spending on physicians/providers/supplies (23%) and Part B and Part D prescription drugs (21%).

How does Medicare per capita spending differ for decedents under and over age 65, and what accounts for the difference in spending?

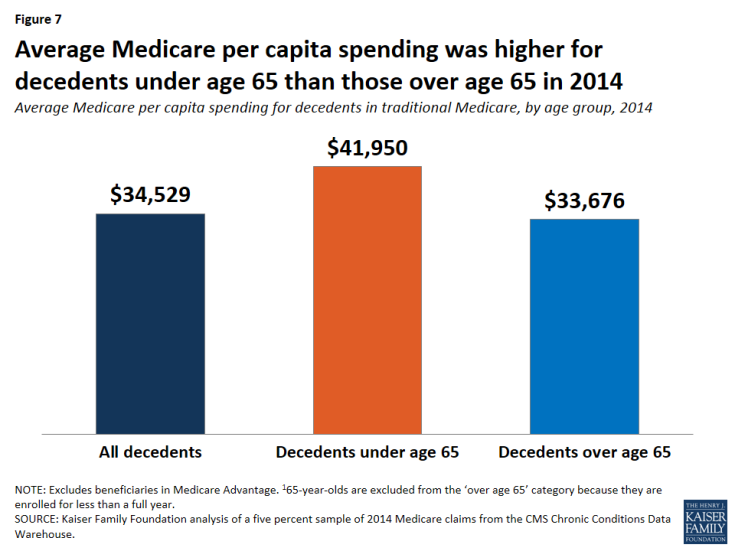

Medicare per capita spending was higher for decedents under age 65 in 2014 than for those over age 65.

- Among decedents in traditional Medicare in 2014 who were younger than age 65, Medicare per capita spending was $41,950, on average (Figure 7). This amount is 25% more than average per capita spending among decedents over age 65 in 2014 ($33,676).

- The fact that Medicare per capita spending is higher for decedents under age 65 than those over age 65 is related to the fact that a larger share of traditional Medicare beneficiaries under age 65 who died at some point in 2014 is dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid than of decedents who are over age 65, and their Medicare per capita spending is significantly higher, on average, than dually eligible beneficiaries over age 65. Among dually eligible decedents in 2014, average Medicare per capita spending among those under age 65 was $51,997, compared to $36,037 among those over age 65.

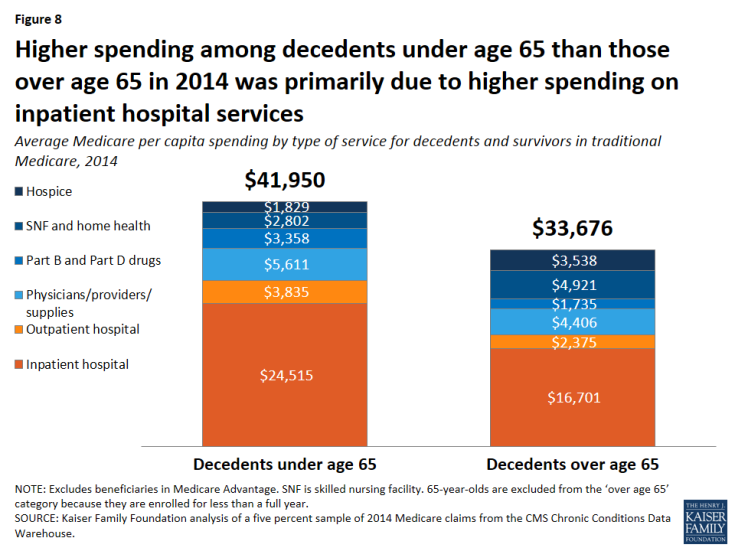

- In terms of Medicare spending by type of service, higher per capita spending among decedents under age 65 than among those over age 65 was driven by higher spending on inpatient hospital services ($24,515 versus $16,701, respectively), along with higher spending on outpatient hospital, physician/providers/supplies, and Part B/D prescription drugs (Figure 8). By contrast, among decedents over age 65, spending was higher on post-acute care and hospice care.

How does medicare per capita spending differ among decedents over age 65?

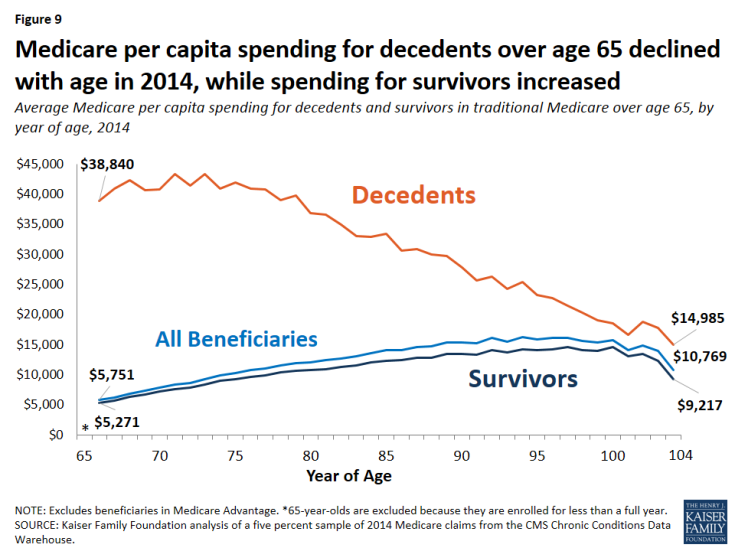

Per capita Medicare spending generally declines with age among decedents in traditional Medicare who are over age 65.

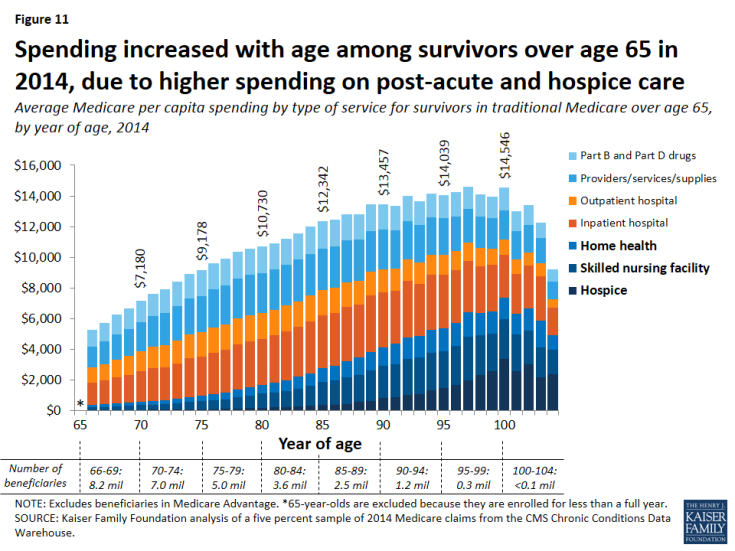

- Among decedents over age 65, Medicare per capita spending was highest for those in their early 70s and then declined with each year of age in 2014 (Figure 9). Among survivors over age 65, the opposite pattern occurred, with spending rising steadily with each year of age in 2014.

What services account for the difference in spending by age among decedents over age 65?

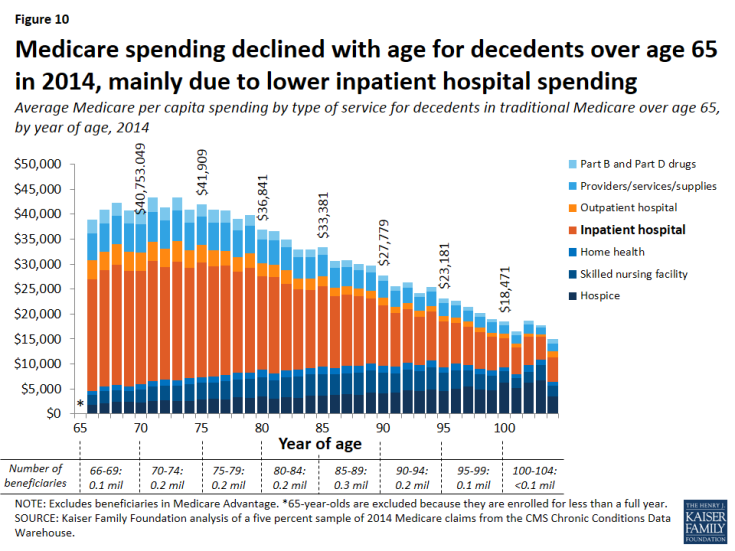

The decline in Medicare per capita spending by age for decedents over age 65 in 2014 was mainly due to lower inpatient spending.

- Per capita Medicare spending on inpatient hospital services decreased steadily with age among decedents in 2014 (Figure 10; Table 3), declining from more than $20,000 for decedents in their late sixties and seventies to around $10,000 or less among decedents older than age 90. In contrast, per capita spending for hospice services increased with age among decedents, from around $2,000 to $5,000 or more between the ages of 66 and 100. Spending on post-acute care (SNF and home health) also increased with advancing age.

- In contrast, spending increased with each year of age among survivors over age 65 in 2014, primarily due to increasing spending on post-acute and hospice care (Figure 11; Table 4). Inpatient hospital care was the costliest type of service for survivors in traditional Medicare up to the early nineties, after which age spending on post-acute care was the largest amount.

Discussion

Much attention has been focused lately on end-of-life care, the services patients receive at the end of life, and Medicare spending on these services. This analysis contributes a number of important findings to the discussion surrounding these issues.

Our analysis shows that Medicare per capita spending for beneficiaries in traditional Medicare who died at some point in 2014 was substantially higher than for those who lived the entire year, as might be expected. It also shows that Medicare per capita spending among beneficiaries over age 65 who die in a given year declines steadily with age. Per capita spending for inpatient services is lower among decedents in their eighties, nineties, and older than for decedents in their late sixties and seventies, while spending is higher for hospice care among older decedents. These results suggest that providers, patients, and their families may be inclined to be more aggressive in treating younger seniors compared to older seniors, perhaps because there is a greater expectation for positive outcomes among those with a longer life expectancy, even those who are seriously ill.

In addition, we find that total spending on people who die in a given year accounts for a relatively small and declining share of traditional Medicare spending. This reduction is likely due to a combination of factors, including: growth in the number of traditional Medicare beneficiaries overall as the baby boom generation ages on to Medicare, which means a younger, healthier beneficiary population, on average; gains in life expectancy, which means beneficiaries are living longer and dying at older ages; lower average per capita spending on older decedents compared to younger decedents; slower growth in the rate of annual per capita spending for decedents than survivors, and a slight decline between 2000 and 2014 in the share of beneficiaries in traditional Medicare who died at some point in each year.

This analysis focuses exclusively on beneficiaries in traditional Medicare, excluding the roughly one in three beneficiaries who are enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans,2 because comparable spending data for Medicare Advantage enrollees are not available. With research showing significant differences in certain demographic and health status characteristics between decedents in traditional Medicare and in Medicare Advantage,3 it is possible that spending and service use patterns may differ as well. While the majority of Medicare beneficiaries who died at some point in 2014 were in traditional Medicare, the inclusion of Medicare Advantage enrollees would provide a better understanding of whether and how the experiences of traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage beneficiaries differ at the end of life.

Decisions pertaining to end-of-life care are among the most difficult for patients, families, and health care providers. The recent change in Medicare payment policy to reimburse physicians for conversations about advance care planning with their patients4 could bring about changes that better align services delivered with patient preferences and that also potentially reduce the costs associated with care at the end of life.

Juliette Cubanski, Tricia Neuman, and Shannon Griffin are with the Kaiser Family Foundation. Anthony Damico is an independent consultant.