Proposals for Insurance Options That Don’t Comply with ACA Rules: Trade-offs In Cost and Regulation

Now in the fifth year of implementation, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) standards for non-group health insurance require health plans to provide major medical coverage for essential health benefits (EHB) with limits on deductibles and other cost sharing. In addition, ACA standards prohibit discrimination by non-group plans: pre-existing conditions cannot be excluded from coverage and eligibility and premiums cannot vary based on an individual’s health status. The ACA also created income-based subsidies to reduce premiums (premium tax credits, or APTC) and cost-sharing for eligible individuals who purchase non-group plans, called qualified health plans (QHPs), through the Marketplace. ACA-regulated non-group plans can also be offered outside of the Marketplace, but are not eligible for subsidies.

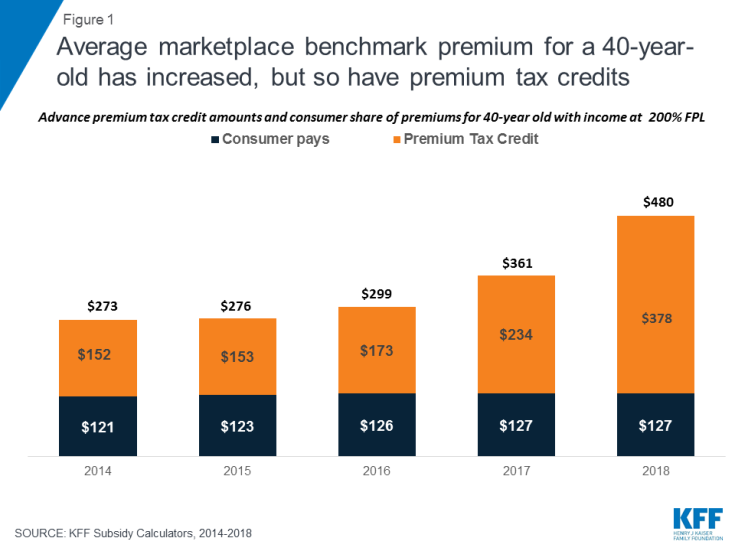

Individual market premiums were relatively stable during the first three years of ACA implementation, then rose substantially in each of 2017 and 2018. Last year, nearly 9 million subsidy-eligible consumers who purchased coverage through the Marketplace were shielded from these increases; but another nearly 7 million enrollees in ACA compliant plans, who do not receive subsidies, were not. Bipartisan Congressional efforts to stabilize individual market premiums – via reinsurance and other measures – were debated in the fall of 2017 and the spring of 2018, but not adopted. Meanwhile, opponents of the ACA at the federal and state level have proposed making alternative plan options available that would be cheaper, in terms of monthly premiums, for at least some people because plans would not be required to meet some or all standards for ACA-compliant plans. This brief explains state and federal proposals to create a market for more loosely-regulated health insurance plans outside of the ACA regulatory structure.

Background

When ACA Marketplaces first opened in 2014, on average, the cost of the benchmark silver QHP was lower than many had predicted. Many insurers underpriced QHPs at the outset, either because they couldn’t accurately predict the cost of providing coverage to a new population under new ACA rules, or to aggressively compete for market share, or both. As a result, insurers offering ACA-compliant policies generally lost money in 2014-2016. In the fall of 2016, for the 2017 coverage year, most issuers implemented a substantial corrective premium increase for their benchmark QHP – on average, a 21% increase for a 40-year-old consumer. This increase, along with growing experience with new market rules, allowed many insurers to regain profitability in 2017, and, going forward, stabilization of QHP rates might otherwise have been expected.

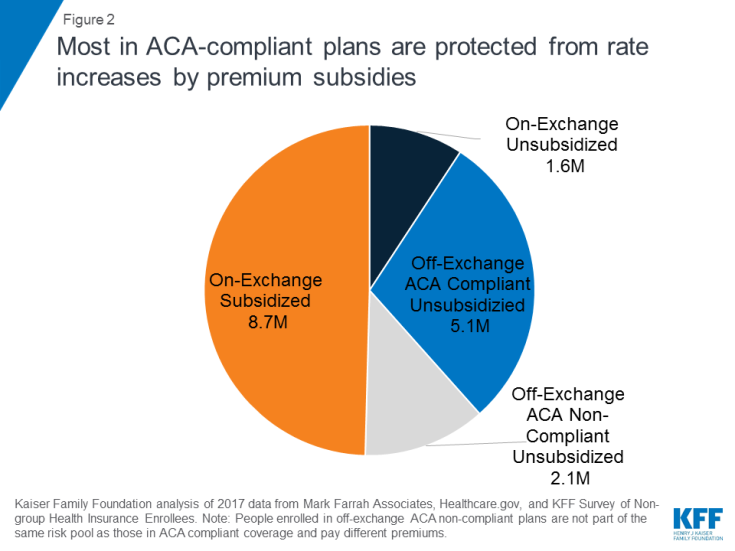

Instead, though, a new wave of uncertainty arose last year as Congress debated repeal of the ACA and as the Trump Administration threatened administrative actions with the stated intent of undermining the program, including by ending reimbursement to insurers for required cost-sharing reductions (CSRs) that, by law, they must offer low-income enrollees in silver QHPs. The value of CSRs was estimated by CBO to be $9 billion for 2018. To compensate for the lost reimbursement, most insurers significantly increased 2018 premiums for silver level QHPs, through which cost sharing subsidies are delivered. Largely due to this so-called “silver load” pricing strategy, the average benchmark silver QHP premium for a 40-year-old rose another 33% for the 2018 coverage year. (Figure 1) Premiums for bronze and gold plans rose more slowly, but still substantially given uncertainty on a number of issues, including whether the ACA’s individual mandate would be enforced.

Figure 1: Average marketplace benchmark premium for a 40-year-old has increased, but so have premium tax credits

For consumers who are eligible for APTC and who buy the benchmark silver plan (or a less expensive plan) through the Marketplace, subsidies absorb annual premium increases and the net cost of coverage has remained relatively unchanged from 2014 through today. Roughly 85% of Marketplace participants in 2017 were eligible for APTC. (Figure 2) However, for the 15% of Marketplace participants who were not eligible for subsidies, and for another roughly 5 million individuals who bought ACA compliant plans outside of the Marketplace, these consecutive annual rate increases threatened to make coverage unaffordable. That threat was even greater in some areas, where 2018 QHP rate increases were much higher than the national average.

Looking ahead, another round of significant premium increases is possible for the 2019 coverage year. A new source of uncertainty arose when Congress voted to end the ACA’s individual mandate penalty, effective in 2019. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated repeal of the mandate would fuel adverse selection – as some younger, healthier consumers might be more likely to forego coverage – and average premiums in the non-group market would increase by about 10 percent in most years of the decade, on top of increases due to other factors such as health care cost growth.

ACA opponents have argued QHP premium increases reflect a failure of the federal law. As an alternative, some have proposed different kinds of health plan options to offer premium relief to consumers who need non-group coverage but who are not eligible for premium subsidies, primarily by relaxing rules governing required benefits, coverage of pre-existing conditions, and/or community rating. These include:

Short-Term, Limited Duration Health Insurance Policies

In 2018 the Trump Administration proposed a new draft regulation that would promote the sale of short-term, limited duration health insurance policies that offer less expensive coverage because they are not subject to ACA market rules.

Short-term limited-duration health insurance policies (STLD), sometimes referred to as limited-duration non-renewable policies, are designed to provide temporary health coverage for people who are uninsured or are losing their existing coverage but expect to become eligible for other, more permanent coverage in the near future. Historically, people who have used these policies include graduating students losing coverage through their parents or their school, people with a short interval between jobs, or newly hired employee subject to a waiting period before they are eligible for coverage from their job. Because these policies are not intended to provide long-term protection (they generally cannot be renewed when their term ends), they are lightly regulated by states and are exempt from many of the standards generally applicable to individual health insurance policies. They also are specifically exempt under the ACA from federal standards for individual health insurance coverage, including the essential health benefits, guaranteed availability and prohibitions against pre-existing condition exclusions and health-status rating. These differences can make them considerably less expensive (for those healthy enough to qualify to buy them) than ACA compliant plans.

STLDs are similar to major medical policies in that they typically cover both hospitalization and at least some outpatient medical services, but unlike ACA-compliant policies, they often have significant benefit and eligibility limitations. STLD policies often either exclude are have significant limitations on benefits for mental health and substance abuse, do not have coverage for maternity services, and have limited or no coverage for prescription drugs. Policies also generally have dollar limits on all benefits or specific benefits and may have deductibles and other cost sharing that is much higher than permitted in ACA-compliant plans. Insurers of STLD policies typically use medically underwriting, which means that they can turn down applicants with health problems or charge them higher premiums. Policies also exclude coverage for any benefits related to a preexisting health condition: a backstop for insurers in case a person with a health problem otherwise qualifies for coverage and seeks benefits. Because STLD policies are not renewable, people who become ill after their coverage begins are generally not able to qualify for a new policy when their coverage term ends.

Due to their lower premiums, some people have been purchasing STLD policies instead of ACA compliant plans. This has happened even though STLD policies are not considered minimum essential coverage, which means that people who purchase them do not satisfy the ACA mandate to have health insurance and may be subject to a tax penalty. In 2016, CMS expressed concern about these policies being sold as a type of “primary health insurance” and issued regulations shortening the maximum coverage period under federal law for STLD policies from less than 12 months to less than three months and prescribing a disclosure that must be provided to new applicants. The intent of the regulation was to limit sale of these policies to situations involving a short gap in coverage and to discourage their use a substitute for primary health insurance coverage. The rule took effect for policies issued to individuals on or after January 1, 2017. In February 2018, the Trump Administration issued a new proposed regulation to reinstate the “less than 12 months” maximum coverage term for STLD policies. The preamble to the proposed regulation specified that this would provide more affordable consumer choice for health coverage. For more information about STLD policies, see this issue brief.

Extending the coverage period for STLD policies back to just under a year is likely to make them a more attractive choice for healthier individuals concerned about the cost of ACA-compliant plans. This is particularly true beginning in 2019 when the individual mandate penalty ends and purchasers will no longer need to pay a penalty in addition to the premiums for these policies.

Under the ACA framework, STLD plans may provide a lower-cost alternative source of health coverage for people in good health. With ACA policies as a backup, people who purchase STLD policies and develop a health problem would not be able to renew their short-term policy at the end of its term, but would be able to elect an ACA-compliant plan during the next open enrollment.

It is possible, as one estimate concluded, that more healthy individual market participants may switch to short-term policies as a result. Such “adverse selection” would raise the average cost of covering remaining individuals in ACA-compliant plans, leading to further premium increases in those policies. For people with pre-existing conditions who do not qualify for subsidies, the rising cost of ACA-compliant coverage could challenge affordability, especially for people with pre-existing conditions who have incomes that make them ineligible for premium subsidies.

Association Health Plans

Another draft regulation proposed by the Trump Administration would permit small employers and self-employed individuals to buy a new type of association health plan coverage that does not have to meet all requirements applicable to other ACA-compliant small group and non-group health plans. While many types of health insurance are marketed though associations, including STLDs, hospital indemnity plans and cancer or other dread disease policies, current policy discussions about AHPs tend to focus on arrangements formed by groups of employers (called multiple employer welfare arrangements, or MEWAs) which could also offer group health insurance coverage to self-employed people without any employees (“sole proprietors”).

The U.S. Department of Labor recently proposed regulations under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) to expand the types of MEWAs that could offer health plans that would not be subject to certain ACA requirements. Under the draft regulation, AHPs – a type of MEWA – could offer health coverage to sole proprietors and to small businesses, but would be subject to large group health plan standards. Key ACA requirements for the non-group and small group market do not apply to large group health plans today, and so would not apply to AHP coverage sold to self-employed individuals or small employers. In particular, AHPs would not be required to cover essential health benefits; it would be possible under the proposed regulation for AHPs to offer policies that do not cover prescription drugs, for example.

Under the draft regulation, AHPs would be subject to a nondiscrimination standard that would prohibit basing eligibility or premiums on an enrollee’s health status. However, other ACA rating standards in the non-group and small group market would not apply; in particular, AHPs would be allowed to vary premiums by more than 3:1 for age and without limit based on gender, geography, and other factors such type of industry or occupation.

As a result, AHPs could provide self-employed individuals an alternative to individual health insurance that provides fewer benefits with more rating flexibility. As nearly one-third (31%) of individual market enrollees are self-employed, the impact of AHPs could be significant.

The draft regulation included other language related to state vs. federal regulatory authority over MEWAs, or AHPs. Currently, MEWAs are subject to a somewhat complex mix of regulatory provisions at the federal and state levels; the applicable standards vary depending on a number of things, including whether the MEWA is self-funded or provides benefits through insurance, whether the arrangement itself is considered to be sponsoring an employee benefit plan as defined in ERISA, the sizes of the employers participating in the arrangement, and how the states in which the arrangements operate approach MEWA regulation. The proposed rule generally leaves in place state authority over MEWAs/AHPs. However, the DOL requested comments on whether it should consider changes that would limit state regulation of self-funded AHPs to financial matters such as solvency and reserves, in effect, prohibiting states from regulating AHP rating and benefit design practices.

The degree of impact on individual health insurance markets will depend in part on the final rules, in particular whether the nondiscrimination provision is preserved and whether states retain current authority over AHPs.

Idaho Proposal for New State-Based Health Plans

In January 2018, pursuant to an executive order by Governor Otter, the Idaho Department of Insurance issued a bulletin outlining provisions of new individual health insurance products that insurance companies would be permitted to sell under state law. The new “State-Based Health Benefit Plans” would not have to comply with certain ACA requirements and, as a result, would likely be offered for premiums lower than those charged for ACA-compliant policies – at least for consumers who are younger and who don’t have pre-existing conditions.

State-Based Health Plans would be required to cover a package of health benefits and cost sharing that was less than that required for ACA-compliant plans. For example, certain essential health benefit categories, such as habilitation services and pediatric dental and vision, appear not to be required. In addition, ACA limits on cost sharing were not specified, and annual dollar limits on covered benefits could be applied. If consumers reach the annual dollar limit on coverage under a state-based plan, the insurer would be required to transfer their enrollment into an ACA-compliant plan.

In addition, state-based plans would not be allowed to deny applicants based on health status and could be sold year round, outside of Open Enrollment. However, State-Based plans could exclude coverage of pre-existing conditions for any individual who had experienced at least a 63-day break in coverage. These plans would also be permitted to vary premiums by a factor of 3:1 based on health status (prohibited by the ACA), and by 5:1 based on age (higher than the 3:1 ratio permitted by the ACA). In order to offer a State-Based Health Plan, insurers would also be required to offer at least one QHP through the Idaho Marketplace.

The bulletin required that state-based plans and exchange-certified plans must comprise a single risk pool, with a single index rate for all plans that does not account for differences in the health status of individuals who enroll, or are expected to enroll in a particular type of plan. However, the Academy of Actuaries noted that, because the two types of plans would not be competing under the same rules, “there would be, in effect, two risk pools – one for ACA coverage and one for state-based coverage. Premiums for ACA coverage would increase, threatening sustainability of the ACA market and its pre-existing condition protections.”

The Idaho State-Based Health Plan proposal is similar in many respects to an amendment offered by Senator Ted Cruz during the ACA repeal debate in 2017. The amendment, which was not enacted, would have allowed insurers that sell ACA-compliant marketplace plans to also offer other policies that could be medically underwritten and that would not have to meet other ACA standards. Although CBO did not estimate how the amendment would impact premiums or coverage, representatives of the insurance industry predicted that, “As healthy people move to the less-regulated plans, those with significant medical needs will have no choice but to stay in the comprehensive plans, and premiums will skyrocket for people with preexisting conditions. This would especially impact middle-income families that that are not eligible for a tax credit.”

The Idaho proposal appears to be not moving forward at this time. Recently, the director of the federal Center on Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) advised Idaho officials that these State-Based health plans would be in violation of federal law. Under the ACA, states do not have flexibility to authorize the sale of individual health insurance policies that do not meet federal minimum standards. In states that do not enforce federal minimum standards, the federal government is required to step in and enforce.

The CMS letter did generally express sympathy with Idaho’s approach, citing “damage caused by the [ACA],” and encouraged the state to pursue modified strategies to expand availability of more affordable plans that do not meet all ACA requirements. The letter specifically urged Idaho to consider promoting short-term policies as a legal alternative to ACA-compliant health plans, and it invited the State to develop other alternative strategies using ACA state waiver authority.

Farm Bureau Health Plans Exempt from State Regulation

A new Iowa law enacted this month would permit the sale of health coverage by the state’s Farm Bureau. The Farm Bureau is not a licensed health insurer. Under the new law, Farm Bureau health plans would be deemed to not be insurance and explicitly would not be subject to state insurance regulation. By extension, Farm Bureau plans also would not have to meet federal ACA standards for health insurance as these apply only to policies sold by state licensed health insurers.

The new Iowa law applies no other standards for Farm Bureau health plans – for example, it does not establish minimum benefit requirements, rating requirements, or rules prohibiting discrimination based on pre-existing health conditions. Appeal rights guaranteed to health insurance policyholders also would not apply to Farm Bureau enrollees, nor would state insurance solvency and other financial regulations. The law does require the Farm Bureau to administer coverage through a state licensed third party administrator, or TPA (expected to be Wellmark, Iowa’s Blue Cross Blue Shield insurer.) However, use of a TPA does not extend federal or state insurance law to the underlying Farm Bureau health plan.

The Iowa law closely resembles a Tennessee state law, enacted in 1993, which authorized the sale of health coverage by the Farm Bureau and deemed such coverage not to be health insurance subject to state regulation. In Tennessee, it has been reported that roughly 25,000 residents purchase non-group Farm Bureau health plans that are medically underwritten. (By comparison, more than 228,000 residents have ACA-compliant individual policies through the Marketplace this year.) Farm Bureau plan premiums can be as much as two-thirds lower than for ACA-compliant plans because the underwritten policies can and do deny coverage to people with pre-existing conditions. Adverse selection results, with sicker residents confined to the ACA-regulated market. An analysis of risk scores for state insurance markets finds that Tennessee’s individual market has one of the highest risk scores in the nation.

Since 2014, Tennessee residents who buy underwritten Farm Bureau health coverage are not considered to have “minimum essential coverage” and so may owe a tax penalty under the ACA individual mandate. However, this disincentive to purchase Farm Bureau plans in Tennessee and Iowa will end in 2019 when repeal of the mandate penalty takes effect.

Discussion

Each of these proposals follows a similar theme. Creating parallel insurance markets with different, lesser consumer protections, allows insurers to offer lower premiums and less coverage to people while they are healthy, leaving the ACA-regulated market with a sicker pool and higher premiums. Once repeal of the ACA individual mandate penalty takes effect in 2019, the net cost differential between regulated and less-regulated coverage will be even greater.

Premium subsidies in the ACA-regulated market will help to curb adverse selection, protecting people with lower incomes from the impact of higher premiums, and providing some continued stability in the reformed market. However, middle-income people who are not eligible for subsidies, and who have pre-existing conditions, will not have any meaningful new coverage choices under these proposals. Instead, the cost of health insurance that covers essential benefits and their pre-existing conditions will increase, potentially further pricing them out of affordable coverage altogether.