Medicaid and Long-Term Services and Supports: A Primer

Medicaid is the nation’s major publicly-financed health insurance program, covering the acute and long-term services and supports (LTSS) needs of millions of low-income Americans of all ages. With limited coverage under Medicare and few affordable options in the private insurance market, Medicaid will continue to be the primary payer for a range of institutional and community-based LTSS for people needing assistance with daily self-care tasks. Advances in assistive and medical technology that allow people with disabilities to be more independent and to live longer, together with the aging of the baby boomers, will likely result in increased need for LTSS over the coming decades. To reduce unmet need and curb public health care spending growth, state and federal policymakers will be challenged to find more efficient ways to provide high quality, person-centered LTSS across service settings. This primer describes LTSS delivery and financing in the U.S., highlighting covered services and supports, types of care providers and care settings, beneficiary subpopulations, costs and financing models, quality improvement efforts, and recent LTSS reform initiatives.

What Are Long-Term Services and Supports?

“Long-term services and supports” encompasses the broad range of paid and unpaid medical and personal care assistance that people may need – for several weeks, months, or years – when they experience difficulty completing self-care tasks as a result of aging, chronic illness, or disability.

Long-term services and supports provide assistance with activities of daily living (such as eating, bathing, and dressing) and instrumental activities of daily living (such as preparing meals, managing medication, and housekeeping). Long-term services and supports include, but are not limited to, nursing facility care, adult daycare programs, home health aide services, personal care services, transportation, and supported employment as well as assistance provided by a family caregiver. Care planning and care coordination services help beneficiaries and families navigate the health system and ensure that the proper providers and services are in place to meet beneficiaries’ needs and preferences; these services can be essential for LTSS beneficiaries who often have substantial acute care needs as well.

Where Are Long-Term Services and Supports Provided and By Whom?

Long-term services and supports are delivered in institutional and home and community-based settings.

These include institutions (such as nursing facilities and intermediate care facilities for individuals with intellectual disabilities) and home and community-based settings (such as group homes or apartments).1 Over the last twenty years, there has been a shift toward serving more people in home and community-based settings rather than institutions due in large part to the growth in beneficiary preferences for home and community-based services (HCBS) and states’ obligations under the Supreme Court’s Olmstead decision which found that the unjustified institutionalization of persons with disabilities violates the Americans with Disabilities Act.2

Long-term services and supports are provided by unpaid family caregivers and by paid providers.

In the U.S., the majority of LTSS is provided by unpaid caregivers – relatives and friends – in home and community-based settings, allowing many with LTSS needs to age in place. According to a 2012 nationally representative survey, the majority of family caregivers are women age 50 and over who care for a parent for at least one year while maintaining outside employment.3 This unpaid care ranges from help with getting to doctor appointments or paying bills to more intensive care such as assisting with bathing or wound care. As a person’s daily care needs become more extensive, paid LTSS delivered by direct care workers – medical professionals (such as physicians or nurses) or para-professionals (such as nurse aides or personal attendants) – may be required in addition to or in place of family caregiver services.

Who Needs Long-Term Services and Supports?

Millions of Americans – children, adults, and seniors – need to access long-term services and supports as a result of disabling conditions and chronic illnesses.

People needing LTSS include elderly and non-elderly people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, physical disabilities, behavioral health diagnoses (such as dementia), spinal cord or traumatic brain injuries, and/or disabling chronic conditions. A beneficiary’s age, gender, socioeconomic status, living arrangement, and access to information about care options, in addition to his or her health and disability status, can influence the types and amounts of LTSS utilized and the duration of care.4,5 People with current or future LTSS needs access information about available services and providers via information and referral networks (such as local Aging and Disability Resource Centers and Area Agencies on Aging) and outreach initiatives (such as peer-to-peer outreach in nursing home-to-community transition programs). The LTSS beneficiary population is growing more racially and ethnically diverse, which has implications for ensuring cultural competency and language access in outreach, assessment, care planning, and service delivery policies and practices.

Demographic trends suggest considerable growth in the number of Americans who will need LTSS in the coming decades.

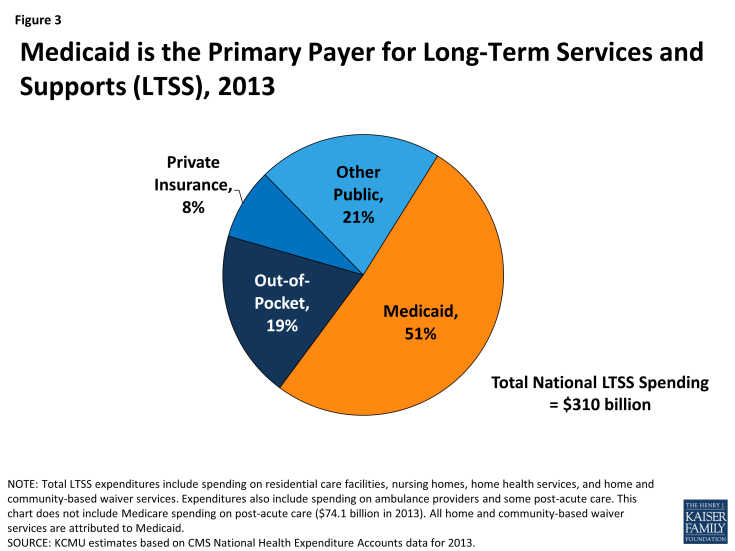

Life expectancy remains relatively high, baby boomers continue to age into older adulthood, and advances in assistive and medical technology allow more people with chronic illnesses and disabling conditions to live longer and independently in the community. The number of elderly Americans is expected to more than double in the next 40 years (Figure 1). According to 2012 estimates, among people age 65 and over, an estimated 70 percent will use LTSS, and people age 85 and over – the fastest growing segment of the U.S. population – are four times more likely to need LTSS compared to people age 65 to 84.6,7 Approximately seven in ten people age 90 and above have a disability, and among people between the ages of 40 and 50, almost one in ten, on average, will have a disability that may require LTSS.8

Figure 1: The 65 and Over Population Will More Than Double and the 85 and Over Population Will More Than Triple by 2050

How Much Do Long-Term Services and Supports Cost and Who Pays For Them?

Long-term services and supports are expensive, with institutional care costs exceeding costs for home and community-based services and supports.

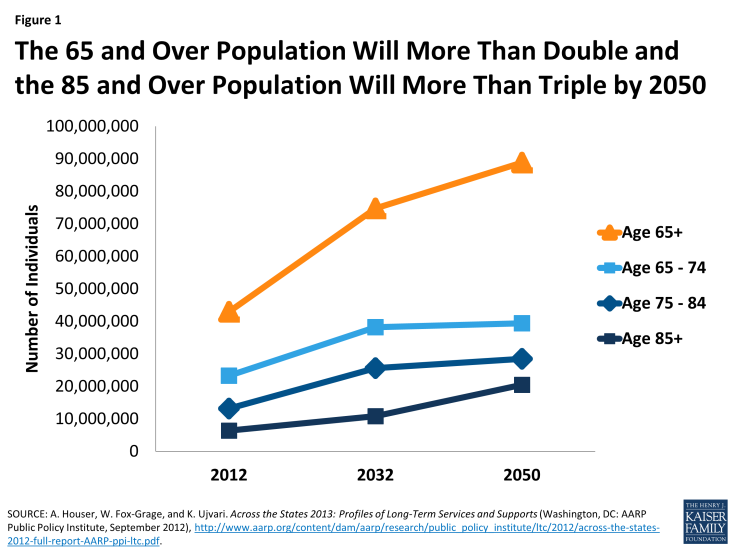

Beyond unpaid care provided by relatives, LTSS costs often exceed what individuals and families can afford given other personal and household expenses. Institutional settings such as nursing facilities and residential care facilities are the most costly. In 2015, the median annual cost for nursing facility care was $91,250.9 Generally, HCBS are less expensive than institution-based LTSS, but may still represent a major financial burden for individuals and their families. In 2015, the median cost for one year of home health aide services (at $20/hour, 44 hours/week) was almost $45,800 and adult day care (at $69/day, 5 days/week) totaled almost $18,000 (Figure 2).10

Figure 2: Long-Term Services and Supports Are Expensive, Often Exceeding What Beneficiaries and Their Families Can Afford

Long-term services and supports are financed with private and public dollars, with the majority covered by publicly financed health insurance programs.

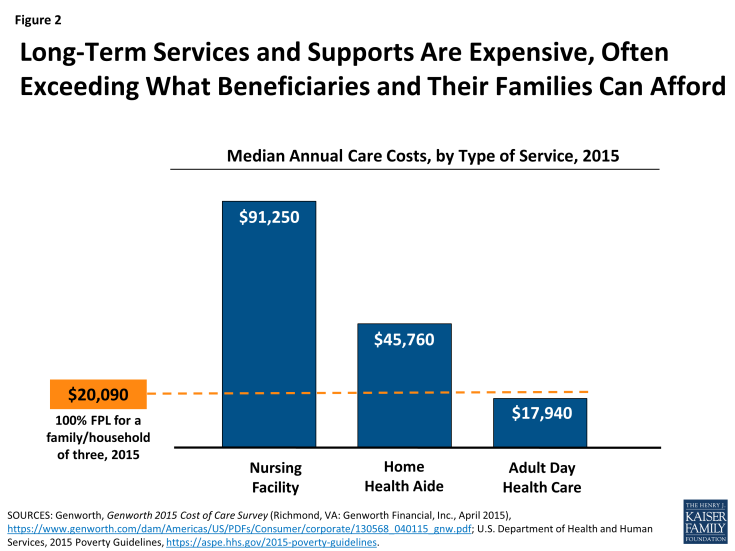

With few affordable options in the private insurance market and limited coverage under Medicare, those with insufficient resources rely on Medicaid. According to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) National Health Expenditure Accounts data, total national spending on LTSS was $310 billion in 2013, with Medicaid covering 51 percent of total expenditures followed by other public,11 out-of-pocket spending, and private insurance (Figure 3).

Medicaid is the primary payer for institutional and community-based long-term services and supports. Medicaid, the nation’s main public health insurance program for people with low income, is administered by states within broad federal rules and financed jointly by states and the federal government. In 2013, Medicaid outlays for institutional and community-based LTSS totaled just over $123 billion, accounting for about 28 percent of total Medicaid service expenditures that year.12 Medicaid eligibility, service delivery, financing, and the new and expanded HCBS options under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) are discussed below.

Medicare coverage of long-term services and supports for seniors, nonelderly people with disabilities, and people with certain chronic conditions is limited. Medicare covers both acute care (such as physician visits) and post-acute services (such as skilled nursing facility care) for people who have a qualifying work history and (1) are age 65 or older; (2) are under age 65 and have been receiving Social Security Disability Insurance for more than 24 months; or (3) have end-stage renal disease or Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis.13 Under Medicare, LTSS coverage is limited. Home health services are only covered for beneficiaries who are homebound, and personal care services are not covered by Medicare. Post-acute nursing facility care is covered for up to 100 days following a qualified hospital stay.

As of 2011, almost 10 million beneficiaries – known as “dual eligibles” – were enrolled in both Medicaid and Medicare, with Medicaid paying for the majority of their long-term services and supports costs.14 The dual eligible beneficiary population comprises seniors and younger people with disabilities who are entitled to Medicare and are also eligible for some level of assistance from their state Medicaid program. Medicare acts as the primary payer for a range of services for dual eligibles; Medicaid provides cost-sharing assistance and may pay for services not covered or limited under Medicare.15,16 In 2011, 62 percent of Medicaid expenditures (or $91.8 billion) for dual eligibles were for LTSS.17 Under new waiver authority in the ACA, selected states are testing models to align Medicare and Medicaid financing, seeking to better integrate and coordinate primary, acute, behavioral health, and LTSS for this vulnerable beneficiary population.18,19

Private long-term care insurance is typically inaccessible to all with current or future care needs often due to high premium prices. Although private long-term care (LTC) insurance, which began as nursing facility insurance, has been available for about 30 years, the market for this insurance product is relatively small. In 2011, 7 to 9 million Americans had private LTC insurance coverage and the average annual premium for an individual policy totaled $2,283.20 Paying for private LTC insurance can be burdensome for individuals and families with limited incomes; this is especially true for seniors who face higher premium costs while living on a fixed income. Furthermore, the benefits are time-limited, so consumers must estimate the amount of time they will require LTSS in the future, which may be difficult to do. Government support for the purchase of private LTC insurance exists in the form of tax incentives and public-private partnerships between states and private insurance companies that allow people with LTSS needs to access Medicaid services, subject to certain eligibility requirements, after purchasing and exhausting benefits under a state-qualified, private LTC insurance policy.21

Few individuals can afford to pay out-of-pocket for needed long-term services and supports, especially those living on fixed incomes with limited personal savings and assets. In 2013, out-of-pocket spending accounted for 19 percent of total national LTSS expenditures.22 A person’s ability to pay for current LTSS needs and/or save for future potential LTSS needs depends on many factors, including, but not limited to, health status, employment status and history, household income, debt and asset levels, and the availability of natural supports (such as a family caregiver); unable to pay, individuals may delay or forego needed formal LTSS. Most seniors have limited resources, with seniors of color facing disproportionately higher economic and health insecurity in retirement.23 In 2013, half of all Medicare beneficiaries, including seniors and younger adults with disabilities, had incomes below $23,500.24

What is Medicaid’s Role in Long-Term Services and Supports Financing?

Medicaid Eligibility

People with long-term services and supports needs may qualify for Medicaid based solely on their low incomes or they may qualify at slightly higher incomes if they also meet disability-related functional criteria. Eligibility criteria vary by state, subject to certain federal minimum requirements. In addition, at state option, people whose income or assets exceed the threshold may later qualify for Medicaid coverage by depleting financial resources, literally “spending down,” to meet the financial eligibility criteria. People seeking Medicaid coverage for nursing facility care must contribute to the cost of care from their monthly income and are subject to an asset transfer review; the transfer of certain assets (such as cash gifts) within the five-year “look back” period may result in a penalty and a period of ineligibility.25 To address the gaps in private LTSS coverage and support people with disabling conditions who desire to secure employment and live in the community, many states opt to allow workers with disabilities to have higher incomes and “buy in” to Medicaid coverage by paying a monthly premium.26

Medicaid Long-Term Services and Supports

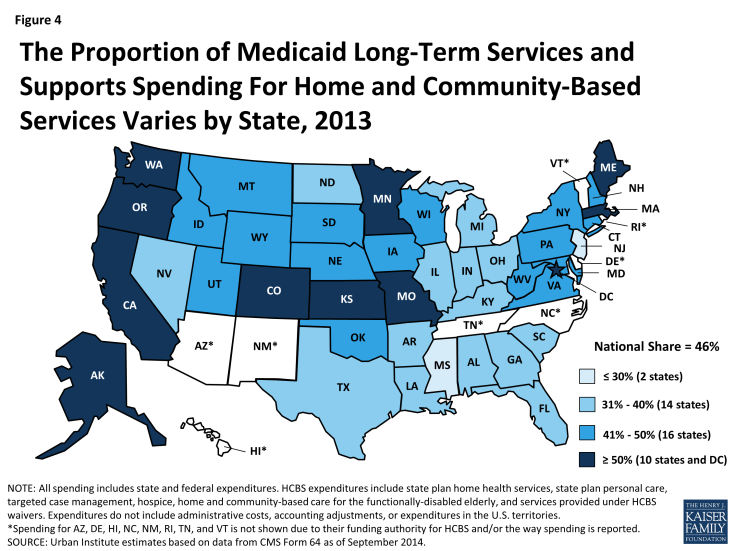

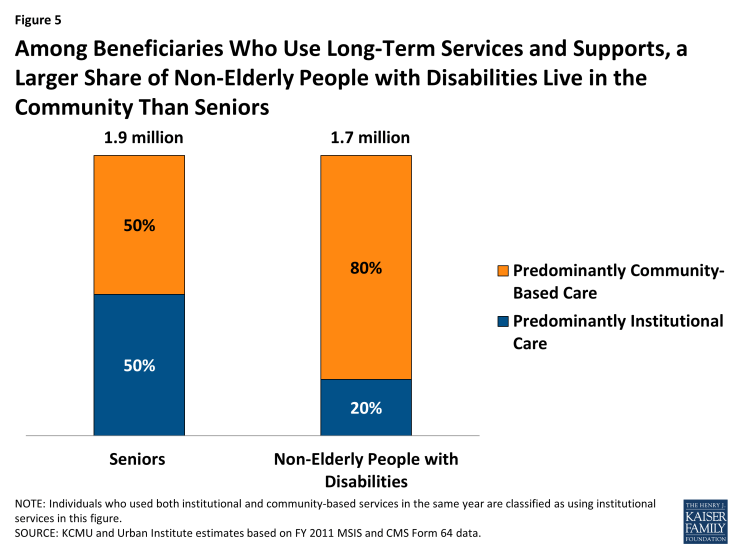

Within the Medicaid program, there has been a historical structural bias toward institutional care. States are required to cover nursing facility benefits, while coverage of most HCBS is optional.27 As a result, Medicaid HCBS spending patterns vary among states, with states spending between 21 percent and 78 percent of their total Medicaid LTSS dollars on HCBS in 2013 (Figure 4).28 In addition, the use of Medicaid HCBS versus institutional services varies across beneficiary subpopulations; in 2011, 80 percent of nonelderly beneficiaries with disabilities used HCBS compared to 50 percent of elderly beneficiaries (Figure 5).29

Figure 4: The Proportion of Medicaid Long-Term Services and Supports Spending For Home and Community-Based Services Varies by State, 2013

Figure 5: Among Beneficiaries Who Use Long-Term Services and Supports, a Larger Share of Non-Elderly People with Disabilities Live in the Community Than Seniors

There has been considerable progress in increasing the amount of Medicaid long-term services and supports dollars spent on community-based services and supports over the last two decades. In 2013, spending on HCBS accounted for 46 percent (or $56.6 billion) of total Medicaid LTSS spending, up from 32 percent (or $29.8 billion) in 2002.30 Three benefits account for the majority of Medicaid HCBS spending: (1) home health services, a mandatory state plan service; (2) personal care services, an optional state plan service; and (3) Section 1915(c) HCBS waivers, which allow states to waive certain federal requirements and provide HCBS to people who otherwise would have to access LTSS in an institutional setting. Just over 3.2 million beneficiaries received home health, personal care, or home and community-based waiver services in 2011, with expenditures totaling $55.4 billion or just about $17,200 per beneficiary.31 In addition, states can use Section 1115 demonstration waivers to deliver HCBS, including through managed LTSS delivery systems (discussed below).32 The Medicaid program also provides authority for beneficiaries to self-direct their HCBS by controlling the selection, training, and dismissal of providers and/or the allocation of their service budget.33

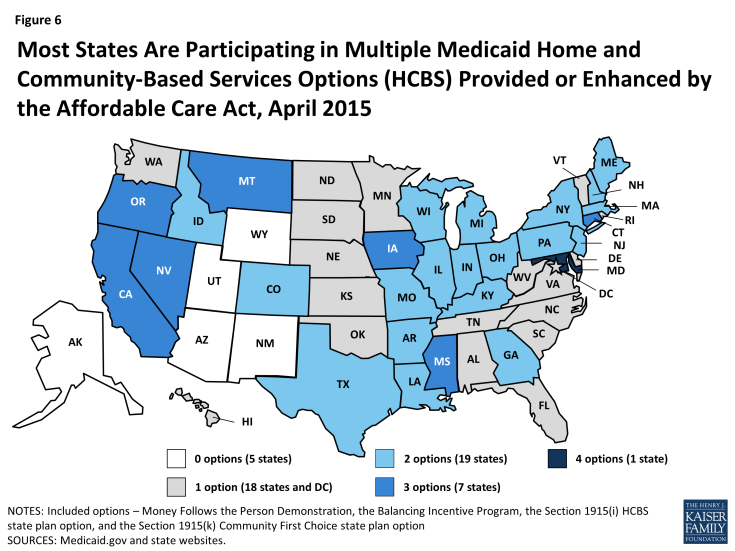

States have numerous options for funding Medicaid home and community-based services, including new and expanded options under the Affordable Care Act.34,35 State implementation of the new and expanded HCBS options under the ACA (i.e., Money Follows the Person Demonstration, the Balancing Incentive Program, the Section 1915(i) HCBS state plan option, and the Section 1915(k) Community First Choice state plan option), some of which provide enhanced federal funding, was relatively slow through 2012. This was due, in part, to competing administrative and fiscal priorities within state Medicaid programs.36 There is now more widespread implementation of the options among states, with numerous states pursuing multiple options either separately or in combination (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Most States Are Participating in Multiple Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services Options (HCBS) Provided or Enhanced by the Affordable Care Act, April 2015

Section 1915(c) waivers accounted for the largest share of Medicaid home and community-based services enrollment and the majority of Medicaid home and community-based services spending in 2011. Expenditures for approximately 1.45 million beneficiaries totaled $38.9 billion across 291 individual Section 1915(c) waiver programs. Not all who are eligible have access to HCBS waiver services as states may implement restrictive financial and functional eligibility standards, enrollment caps, service unit limits, or waiting lists in an effort to contain costs. In 2013, there were over 536,000 individuals in 39 states on a Section 1915(c) waiver waiting list.37

Medicaid Delivery System Reforms

There has been increasing interest among states in transitioning from the traditional fee-for-service financial model to managed care to deliver and coordinate services for Medicaid long-term services and supports beneficiaries. The number of states delivering and financing Medicaid LTSS via a risk-based capitated managed care model is expected to increase,38 and states also are pursuing managed fee-for-service models, including primary care case management. Managed care models, while relatively untested to date, offer potential opportunities for improving care coordination, and/or expanding access to HCBS.39 Given the vulnerability of this beneficiary population, it is important that managed LTSS systems are monitored to ensure access to the necessary services and supports on which beneficiaries rely to live independently in the community.

How is the Quality of Long-Term Services and Supports Evaluated?

Care standards and performance measures are important to inform state and national efforts to improve the quality of long-term services and supports delivered across care settings and service delivery models.

Ensuring timely access to high quality care for people with LTSS needs is a priority for beneficiaries and their families, service providers, and state and federal policymakers alike. However, quality measures for LTSS are not as well developed as those for care provided in clinical settings. In addition, LTSS performance measures can vary by state, prompting efforts to develop a core set of LTSS-specific quality measures to evaluate structural elements (such as provider staffing capacity), service delivery processes (such as timeliness of assessment), or care and performance outcomes (such as an improved ability to complete a self-care task).40,41 Ongoing efforts to streamline assessment processes, improve reporting feedback mechanisms, and examine the effectiveness of LTSS-specific quality standards will be vital to improving service delivery as the LTSS beneficiary population grows and becomes more diverse.

Quality in Institutional settings

Nursing homes certified to participate in the Medicare and Medicaid programs are regulated and must adhere to national and statewide quality assurance and reporting standards, which were expanded by the Affordable Care Act. The ACA, which incorporates the Nursing Home Transparency and Improvement Act, the Elder Justice Act, and the Patient Safety and Abuse Prevention Act, is the first comprehensive institutional care quality legislation since the 1987 Nursing Home Reform Act. The ACA requires CMS and nursing homes to implement provisions aimed at improving transparency and accountability, enforcement, and resident abuse prevention. For example, CMS must establish a national direct care worker payroll data collection and reporting system and add additional facility-level staffing and complaint data to the Nursing Home Compare website,42 and nursing homes must disclose their ownership, management, and financing structures, implement compliance and ethics programs, meet CMS’s quality assurance and improvement standards, and report suspected crimes committed against residents to law enforcement authorities. States and CMS continue to make progress in implementing the federal requirements as the provisions are expected to have a substantial impact on nursing home accountability for care quality.43

Quality in Home and Community-Based Settings

As states continue to increase spending on home and community-based services as an alternative to institutional care, work continues on developing specific quality measures to evaluate and improve home and community-based long-term services and supports. Improving and aligning quality standards across all Medicaid HCBS programs remains a priority for CMS, states, and stakeholders through initiatives such as measurement testing projects and education and training opportunities for states and providers.44 With respect to Section 1915(c) waivers, the largest Medicaid HCBS program, CMS modified the quality assurance reporting system in 2014, with the goal of improving oversight of beneficiary outcomes and realigning state reporting requirements. Examples of ongoing efforts to identify or develop and evaluate HCBS quality measures include the Measure Applications Partnership/National Quality Forum,45 the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services Measure Scan,46 and the Long-Term Care Quality Alliance Quality Measurement Workgroup.47

Managed Long-Term Services and Supports and Quality

Given the growing interest among states in covering new populations and long-term services and supports benefits through risk-based, capitated managed care arrangements, monitoring beneficiaries’ access to care and outcomes in these systems will remain important. In 2013, CMS issued guidance to states outlining best practices for designing and implementing managed LTSS programs with respect to quality measurement and other key program elements. States implementing managed LTSS programs are expected to include a comprehensive quality strategy for assessing and improving care and quality of life for LTSS beneficiaries that aligns with existing Medicaid quality initiatives and systems.48

What Recent Efforts to Reform National Long-term Services and Supports Financing Have Been Initiated?

Established by the Affordable Care Act but later repealed before implementation, the Community Living Assistance Services and Supports (CLASS) program was designed to provide working adults the opportunity to offset the costs of future long-term services and supports needs.49 CLASS was intended to be a national, voluntary insurance program for purchasing LTSS coverage, financed by individual premium contributions, but concerns about solvency and adequacy of the cash benefit led to the program’s repeal by the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2013.50

Under the same law that abolished the Community Living Assistance Services and Supports program, Congress established the time-limited, federal, bipartisan Commission on Long-Term Care. The Commission’s September 2013 Final Report, outlines several service delivery, workforce, and financing policy recommendations, e.g., establishing integrated care teams, using technology-enhanced data sharing across care settings and among providers, training family caregivers, finding a sustainable balance of public and private financing for LTSS.51 (Note: Five members of Commission later issued an independent minority report which outlined alternative recommendations for LTSS reform.52) While the Commission recommended that future work be carried out through a national advisory committee,53 no such committee has been convened to date, although numerous public and private stakeholders remain interested in advancing the national LTSS agenda.54,55

Looking Ahead

Reforming the nation’s long-term services and supports system is likely to remain a topic of discussion in the coming decades as policymakers and other stakeholders consider options for meeting the growing need for community-based options and addressing the lack of long-term services and supports coverage options outside of Medicaid. Given the significant public investment in the delivery and financing of LTSS, policymakers and other stakeholders have a vested interest in exploring LTSS reform options. In the absence of other viable public or private options to finance current and future LTSS needs for people of all ages, Medicaid will continue to be the major financing and delivery system for institutional and community-based LTSS for millions of Americans. Looking ahead, addressing community-based provider and housing shortages and streamlining access to community-based care that supports functional independence and enhances quality of life will remain key objectives of states’ rebalancing efforts as the need for Medicaid HCBS continues to grow. Policymakers and other stakeholders also may focus on the status of Medicaid initiatives to rebalance LTSS in favor of HCBS, with the expiration of Balancing Incentive Program funds in 2015, and Money Follows the Person funds in 2016. As the general LTSS beneficiary population increases and becomes more diverse, state and federal governments and private stakeholders will be challenged to find innovative ways to coordinate, deliver, and finance high quality, person-centered LTSS in the most appropriate care setting that promotes health and well-being, respects beneficiary preferences and rights, and maximizes efficiency to manage cost growth.