Medical Debt Among People With Health Insurance

Consequences of Medical Debt

Across the board, medical debt triggered other hardships and financial instability among every one of the individuals interviewed. Studies of the broader population also find that medical debt can have devastating consequences. People who have difficulty paying medical bills are more likely to forego needed care, for example, by cancelling routine doctor’s appointments, delaying recommended follow-up care, or failing to fill prescriptions.1 In addition, they are significantly more vulnerable to other financial hardship and are also more likely to deplete savings, borrow from relatives, suffer damaged credit, or file for bankruptcy.2

Through case studies, we observed people experienced severe consequences when medical bills became unmanageable:

Damaged credit

Virtually everyone interviewed had experienced substantial damage to their credit rating as a result of medical debt. Generally, when bills are referred for collections, this action can be reported to credit rating agencies. According to industry experts, “If you have an account go into collections and reported on your credit, your credit score will drop by a substantial amount.”3

Most of those interviewed had not experienced credit problems before the medical bills. Once damaged, though, they learned it can take years to restore one’s credit rating. With poor credit, people face difficulty qualifying for mortgages, auto loans, and other consumer credit, or faced higher interest rates. Bad credit can also complicate transactions with new employers, utility companies, insurers, even cell phone companies, who commonly run credit checks on applicants.4

|

Table 4. Description and Implications of Credit Rating Scores

|

||

|

FICO Score

|

Score Description

|

# Case studies*

|

|

850-740

|

Excellent

Insurance companies are more likely to give you absolutely the best deals, because you are less likely to commit fraud. Thanks to your amazing credit responsibility, you are attractive to prospective employers, too.

– Average Mortgage Interest Rates: 3.034%

– Average Auto Loan Interest Rates: 3.321%

|

0

|

|

740-700

|

Good

The majority of credit cards (including those with rewards) are available to you. Rates will be very low or close to zero. Getting an insurance policy should be an easy task, too. Your monthly insurance premiums will be somewhat higher than for those with top scores, however, you should have no problems with getting an insurance policy for literally anything you want.

– Average Mortgage Interest Rates: 3.256%

– Average Auto Loan Interest Rates: 4.754%

|

1

|

|

699-641

|

Average

This score is an absolute minimum to get a fair mortgage and auto loan terms. Insurance policies will be up by a significant amount for people in this range due to the potential risk for non-payment of premiums.

– Average Mortgage Interest Rates: 3.647%

– Average Auto Loan Interest Rates: 6.795%

|

2

|

|

640-500

|

Bad

You represent a very high credit risk to the lenders and you won’t be able to get a mortgage at all (in most cases). You will be able to get an auto loan, but your interest rates will be around 15%. Insurance policy and car insurance will be very limited for you and cost significantly more than for those with good scores. Also, your choice of credit card is very limited if you fall in this range. However, if you still want a credit card, consider choosing a secured credit card.

– Average Mortgage Interest Rates: very hard or impossible

– Average Auto Loan Interest Rates: 15.608%

|

14

|

|

500-300

|

Very Bad

Getting a mortgage with this score is almost impossible. You still may get an auto loan, but expect almost double interest rates. Many banks may not even let you open a checking account with this score. Unfortunately, most insurance companies will refuse to work with you, based on the risks you pose.

– Average Mortgage Interest Rates: very hard or impossible

– Average Auto Loan Interest Rates: 17% or impossible

|

6

|

|

Source: http://creditscoreranger.org/

* Case study credit scores reflect status at time they sought counseling from ClearPoint. Many clients experience further decline in scores before debt problems are resolved.

|

||

Emotional distress

Virtually everyone interviewed expressed feeling shame or embarrassment to be in medical debt. Most had not had any serious financial difficulties or debt problems before medical bills began. Most voiced a strong personal ethic to always pay their bills and were distressed to find themselves in debt. Sonya talked about how juggling bills made her feel “way outside my comfort zone.” She described being in debt as a “nightmare” and filing for bankruptcy was a blow to her pride. Retelling her experiences, she said, was like “opening up a wound.” One person ended up divorced at the end of her ordeal, and said the stress of medical debt was a contributing factor. Another couple stayed together, though debt problems strained their marriage for months.

Economic deprivation

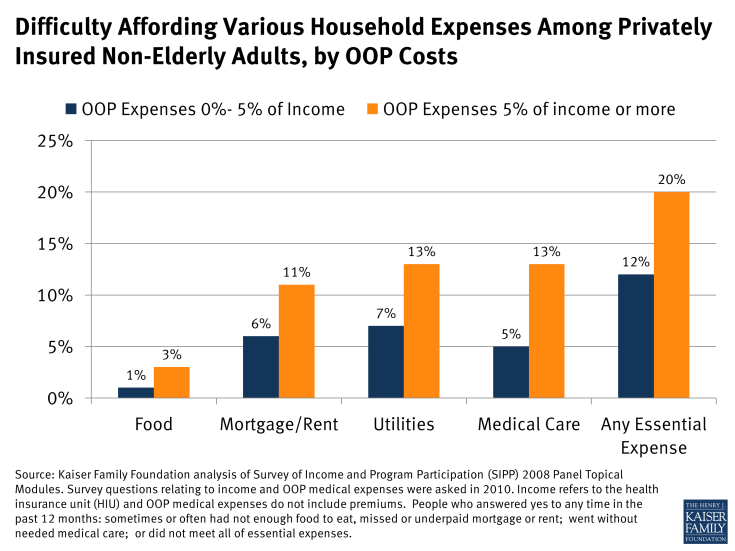

Our analysis of the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) finds that privately insured people with out-of-pocket medical expenses that exceed five percent of their income are about twice as likely to have difficulties paying their rent and utilities, affording food, and to face barriers accessing medical care, compared to those with OOP costs less than five percent of their income.

Most people we interviewed drastically reined in household spending in the face of medical debt. They did without heating oil, groceries, even glasses for their children. A few sold their cars; others took on second part time jobs. Maisy noted, “I’m a pretty notorious penny pincher, and we haven’t bought anything that wasn’t from a thrift store in years, but those sorts of medical debts you just can’t penny-pinch your way out of.” Several people we interviewed were able to consolidate their bills through debt management programs (DMPs) that ClearPoint helped arrange. Stuart expects to pay off all the bills eventually – he’s been paying creditors $1,000 per month under his DMP for the past two years and has one more year to go. Duncan is also paying $1,000 under his DMP to clear up bills from his wife’s cancer treatment that date back to 2010. The DMP installment takes one-third of his take home pay, the mortgage takes another $1000, leaving the family of three just $1,000 per month for everything else. For some, austerity measures were temporary, for others it became their new way of life. As Dorothy put it, “once I thought I was headed toward being middle class, but not now.”

Figure 4: Difficulty Affording Various Household Expenses Among Privately Insured Non-Elderly Adults, by OOP Costs

Depleted long term assets

Eight people we interviewed severely depleted long term assets to pay medical bills. Gwen, 57, took $10,000 out of her 401(k) – one-fifth of the balance – to pay some of the medical bills she owes. She doesn’t expect to retire anytime soon. Charlene, 52, took $23,000 out of retirement savings – it had taken her 14 years to put away that amount – and also cashed out her daughter’s $5,000 college fund to pay medical bills. Stuart didn’t have to tap retirement savings, but, during the period when he incurred large medical bills, he had to reduce what he was paying toward his two sons’ college expenses by several hundred dollars per month. The boys made up the difference by taking out student loans. Kris took out a home equity line of credit to pay about $5,000 in medical bills. His medical bills are paid, but now his mortgage payment is much higher.

Medical bills often trigger such difficult decisions. According to one study, 11 percent of Americans have taken money out of retirement savings to pay medical bills. Described as a “retirement derailer,” such action can significantly delay retirement plans or lead to financial insecurity during retirement.5 Derailers can be particularly problematic for people over age 40, who won’t have as many years to make up for early withdrawals and lost contributions. Another study found that among medically indebted individuals, one fifth used retirement funds and nearly one-quarter withdrew equity from their homes to pay debts.6

Housing instability

Medical debt has also been shown to contribute to housing instability, including missed mortgage or rent payments, property tax liens, difficulty qualifying for loans, eviction, disruptive moves to less expensive housing, rental applications denied and in extreme circumstances, homelessness. According to one study, 27 percent of people with medical debt also experienced such housing-related problems.7

Several whom we interviewed found their homes threatened by medical bills. Some fell behind on rent or mortgage payments for a few months, then were able to get caught up; others never recovered and lost their homes. Gwen was determined to pay the $40,000 in her husband’s medical bills that insurance wouldn’t cover. When she asked her mortgage company if they would revise her loan and lower the monthly payment, she was told such programs were only for clients who were in arrears, so she skipped a few payments. The bank still refused to modify her loan, however, and a few months later started foreclosure proceedings. Gwen decided she would be better able to pay past debts, as well as new bills for her husband’s ongoing care, if she didn’t pay the mortgage so, as she put it, “I let them take the house.” A friend found a less expensive, smaller place that Gwen and George now rent. Connie and her family of four lost their home to foreclosure, as well. Her husband was injured in an auto accident and for several years she tried to juggle bills, including the mortgage, to keep pace with medical bills. The bank foreclosed in 2010, and Connie and her family moved back to Oklahoma to live in a relative’s home.

Bankruptcy

Medical bills are a leading cause of personal bankruptcy in the U.S., contributing to 62 percent of personal bankruptcies in 2007. Most who filed for medical bankruptcy that year were well educated, owned homes, and had middle-class occupations. Three quarters had health insurance.8

Of the 23 persons interviewed for this report, 15 had filed for bankruptcy. Most filed under Chapter 7 – meaning their debts were discharged. A few filed under Chapter 13, and so agreed to pay most or all of their unsecured debts over a period of time, typically three to five years, under a court-ordered payment plan. While these individuals expressed some relief at the protection afforded them; most did not want to resort to bankruptcy and many resisted filing as long as they could. Seven filed only after tapping retirement or college savings to pay medical bills or losing their home to foreclosure – assets that would have been protected under a bankruptcy filing. Two others either lost their home or borrowed against their home in lieu of filing for bankruptcy. And, though bankruptcy is considered a last-resort solution, nine of those who filed for bankruptcy have since incurred significant new medical bills and worry what will happen if they can’t pay those since they won’t be allowed to file for bankruptcy protection again for many years.

Difficulty accessing care

Finally, many studies have documented that that people with unaffordable medical bills also tend to experience difficulties accessing care.9 In some cases, providers may refuse to treat patients who cannot pay their bills. Kieran, for example, reported that one hospital to which he owed money refused to pre-register his wife for a hospitalization until overdue bills were paid. More often, people we interviewed decided to forego care in order to avoid incurring even more bills they could not afford. Dillon, for example, put off needed dental care because he already was struggling to pay thousands of dollars in medical debts to other providers. Jeanne, a cancer survivor, delayed recommended follow up visits until she could assemble the cash to pay for them.