President Trump’s Proclamation Suspending Entry for Immigrants without Health Coverage

Introduction

On October 4, 2019, President Trump released a proclamation suspending entry of immigrants into the United States unless they provide proof of health insurance within 30 days of entry or have financial resources to pay for reasonably foreseeable health insurance costs. The proclamation indicates that the suspension is necessary to protect the health care system and taxpayers from uncompensated care costs. This brief provides an overview of the proclamation and data on health coverage and health care use for immigrants.

Overview of Proclamation

Effective November 3, 2019, the proclamation would suspend entry of immigrants unless they can prove they will be covered by approved health insurance within 30 days of entry into the U.S. or that they have financial resources to pay for reasonably foreseeable medical costs.

Approved health coverage. Under the proclamation, approved health insurance would include employer-sponsored and other private coverage, including unsubsidized coverage through the ACA Marketplaces, short-term plans, traveler plans, or catastrophic plans. Subsidized Marketplace coverage and Medicaid coverage for adults would not count as approved coverage. State or local programs and other programs, like Ryan White, are also not included as approved coverage in the proclamation.

Individuals subject to suspension. The suspension would apply to individuals seeking an immigrant visa on or after November 3, 2019. The new requirement would primarily affect family-based immigrants. It would not apply to refugees, asylees, people entering as non-immigrants, and certain other groups. Children under age 18 are subject to suspension if they are traveling with a parent who is also subject to the suspension.

Individuals subject to the proclamation will need to establish that they meet its requirements to the satisfaction of a consular officer before an immigrant visa is issued. The proclamation indicates that the Secretary of State may establish standards and procedures for these determinations.

An earlier regulation from the Trump administration made changes to public charge policies that will make it harder for immigrants to adjust to lawful permanent resident status or get a green card if they are low-income, sick, or likely to enroll in Medicaid. It is likely that the confusion and chilling effect surrounding the regulation will lead to declines in Medicaid and CHIP coverage among immigrant families beyond those directly affected by the changes and increase the uninsured rate among immigrant families.

Health Coverage and Health Care for Immigrants

In 2017, there were 22 million noncitizens residing in the United States, accounting for about 7% of the total U.S. population.1 About six in ten noncitizens were estimated to be lawfully present immigrants, while the remaining four in ten were estimated to be undocumented immigrants:2 Many individuals live in mixed immigration status families that may include lawfully present immigrants, undocumented immigrants, and/or citizens.

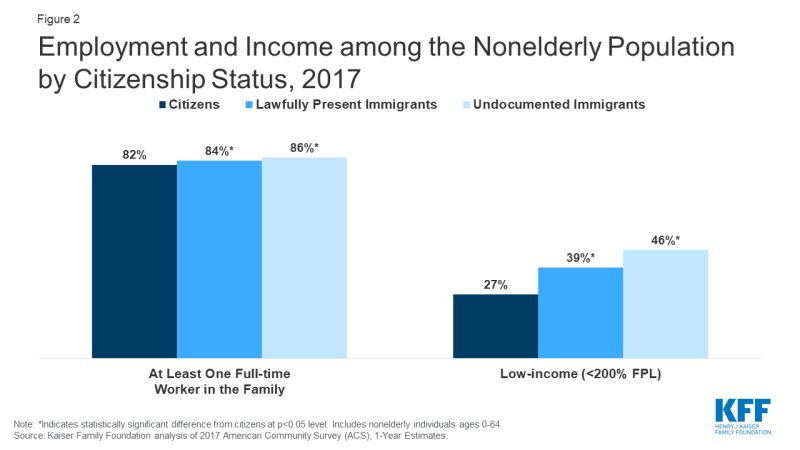

Noncitizens are more likely to be uninsured than citizens, but citizens account for the majority of the total uninsured. Noncitizens, including lawfully present and undocumented immigrants, are significantly more likely to be uninsured than citizens, reflecting limited eligibility for coverage options and enrollment barriers. As of 2017, among the total nonelderly population, 23% of estimated lawfully present immigrants and more than four in ten (45%) estimated undocumented immigrants were uninsured compared to fewer than one in ten (8%) citizens (Figure 1). Despite the higher uninsured rate among noncitizens, citizens still accounted for three-quarters of the total 27.4 million uninsured.

Figure 1: Uninsured Rates and Distribution of the Uninsured among the Nonelderly Population by Immigration Status, 2017

The higher uninsured rates among noncitizens reflect limited access to employer-sponsored coverage; eligibility restrictions for Medicaid, CHIP, and ACA Marketplace coverage; and barriers to enrollment among eligible individuals.

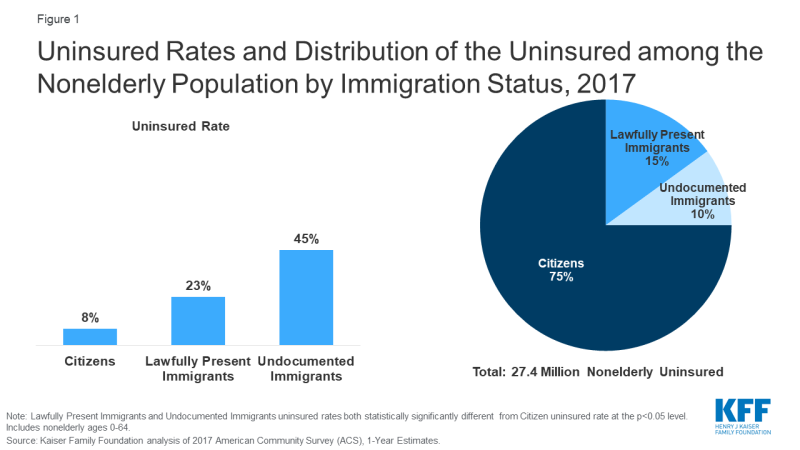

- Although most nonelderly noncitizens live in a family with a full-time worker, they face gaps in access to private coverage. Nonelderly noncitizens are more likely than nonelderly citizens to live in a family with at least one full-time worker, but they also are more likely to be low-income (Figure 2). They have lower incomes because they are often employed in low-wage jobs, and they work in industries that are less likely to offer employer-sponsored coverage. Further, given their lower incomes, noncitizens face increased challenges affording employer-sponsored coverage when it is available or purchasing coverage through the individual market.

- Lawfully present immigrants may qualify for Medicaid and CHIP but are subject to certain eligibility restrictions. In general, lawfully present immigrants must have a “qualified” immigration status to be eligible for Medicaid or CHIP and many, including most LPRs or “green card” holders, must wait five years after obtaining qualified status before they may enroll. States have an option to eliminate the five-year wait for lawfully residing immigrant children and pregnant women, and half of states (24) apply the option to both children and pregnant women, while ten states use it for children only, and one state (Wyoming) uses it only for pregnant women.3 Lawfully present immigrants can purchase coverage through the ACA Marketplaces and may receive subsidies for this coverage within the five-year waiting period. Undocumented immigrants are not eligible to enroll in Medicaid or CHIP or to purchase coverage through the ACA Marketplaces.

- Many lawfully present immigrants who are eligible for coverage remain uninsured because immigrant families face a range of enrollment barriers, including fear, confusion about eligibility policies, difficulty navigating the enrollment process, and language and literacy challenges.

Research shows immigrants tend to be younger and healthier and to use less health care than U.S born individuals. Data show that immigrants spend less on health care, compared to their U.S. born counterparts, and make larger out-of-pocket health care payments compared to nonimmigrants.4 Immigrants have lower spending, in part, because they use less care due to their low coverage rates and limited access to care.5 They also tend to be younger and healthier than nonimmigrants, although this health difference decreases over time as immigrants spend longer in the United States.6

Though uninsured people are less likely to access care than those with coverage, when they do seek care they are typically billed for these services. Most uninsured people do not receive health services for free or at reduced charge, and many are asked to pay in full up front before they receive care.7 As a result, when uninsured people use care, they are at risk of incurring medical debt. Like other uninsured individuals, many immigrants without coverage can obtain low-cost care through community health centers. Moreover, under federal law, hospitals are required to screen and stabilize every patient who seeks emergency care.

Some of the cost of care for uninsured people is converted to uncompensated care for providers, but uncompensated care costs have declined in recent years and immigrants likely account for a small share of uncompensated care costs. When uninsured people are unable to pay their bills, providers absorb some of the cost of care for the uninsured. Some uncompensated care is offset by private or public programs specifically for this purpose. In recent years, uncompensated care costs have declined due to coverage expansions under the Affordable Care Act (ACA).8 Further, there is limited evidence that uncompensated care for uninsured patients is associated with hospitals charging higher prices for those who are privately insured.9 Given that immigrants account for a small share of the total uninsured population and that they use less care compared to the U.S. born, they likely account for a small share of total uncompensated care costs.

Endnotes

Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of 2017 American Community Survey (ACS), 1-Year Estimates.

The estimate of the total number of non-citizens in the US is based on the 2017 American Community Survey (ACS). The ACS does not include a direct measure of whether a non-citizen has legal status or not. We impute documentation status by drawing on methods underlying the 2013 analysis by the State Health Access Data Assistance Center (SHADAC) and the recommendations made by Van Hook et. al.. This approach uses the second wave of the 2008 Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) to develop a model that predicts immigration status for each person in the sample; it then applies the model to a second data source, controlling to state-level estimates of total undocumented population as well as the undocumented population in the labor force from the Pew Research Center. See, “U.S. Unauthorized Immigrant Total Dips to Lowest Level in Decade,” available here: http://www.pewhispanic.org/2018/11/27/u-s-unauthorized-immigrant-total-dips-to-lowest-level-in-a-decade/.

Tricia Brooks, Lauren Roygardner, and Samantha Artiga. Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility, Enrollment, and Cost Sharing Policies as of January 2019: Findings from a 50-State Survey. (Washington, DC: The Kaiser Family Foundation, 2019), https://www.kff.org/report-section/medicaid-and-chip-eligibility-enrollment-and-cost-sharing-policies-as-of-january-2019-findings-from-a-50-state-survey-medicaid-and-chip-eligibility/

Lila Flavin, Leah Zallman, Danny McCormick, and J. Wesley Boyd, Medical Expenditures on and by Immigrant Populations in the United States: A Systematic Review, (Boston, MA: Tufts University School of Medicine, 2018), https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0020731418791963

Ibid.

Ibid.

Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of the 2015 Kaiser Family Foundation/New York Times Medical Bills Survey.

Larisa Antonisse, Rachel Garfield, Robin Rudowitz, and Madeline Guth. The Effects of Medicaid Expansion under the ACA: Updated Findings from a Literature Review. (Washington, DC: The Kaiser Family Foundation, 2019), https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-effects-of-medicaid-expansion-under-the-aca-updated-findings-from-a-literature-review-august-2019/

Teresa A. Coughlin, John Holahan, Kyle Caswell, and Megan McGrath. Uncompensated Care for the Uninsured in 2013: A Detailed Examination. (Washington, DC: The Kaiser Family Foundation, 2014), https://www.kff.org/uninsured/report/uncompensated-care-for-the-uninsured-in-2013-a-detailed-examination/