Implementing Coverage and Payment Initiatives: Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2016 and 2017

Emerging Delivery System and Payment Reforms

| Key Section Findings |

Tables 10 and 11 contain more detailed information on emerging delivery system and payment reform initiatives in place in FY 2015, implemented in FY 2016, or planned for FY 2017. |

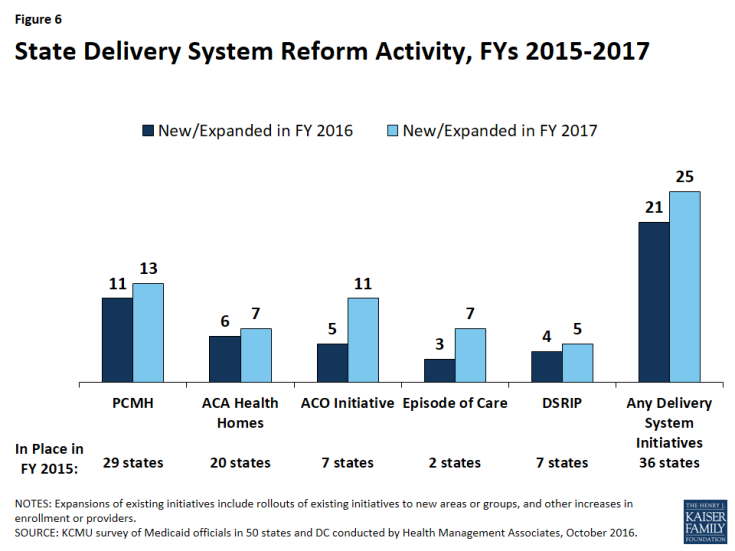

This year’s survey asked states to identify which delivery system and payment reform models were in place in FY 2015, and whether they had adopted or were enhancing such models in FY 2016 or FY 2017. Over two-thirds of all state Medicaid programs, 36 states in FY 2015 and 39 states in FY 2016, currently have at least one delivery system or payment reform initiative in place designed to improve health outcomes and constrain cost growth (Figure 6 and Table 10). If all actions reported by states for FY 2017 are implemented as planned, that number will grow to 42 states by the end of FY 2017, demonstrating the continued widespread and growing interest in Medicaid transformation. A total of 21 states in FY 2016 and 25 states in FY 2017 reported adopting or expanding one or more initiatives that seek to reward quality and encourage integrated care. Key initiatives include patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs), Health Homes, and Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs). Interest in Episode of Care initiatives also ticked upward for FY 2017 (Figure 6 and Table 11).

Patient-Centered Medicaid Homes (PCMHs)

PCMH initiatives operated in over half (29) of Medicaid programs in FY 2015 (Table 10). Under a PCMH model, a physician-led, multi-disciplinary care team holistically manages the patient’s ongoing care, including recommended preventive services, care for chronic conditions, and access to social services and supports. Generally, providers or provider organizations that operate as a PCMH seek recognition from organizations like the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA).1 PCMHs are often paid (by state Medicaid agencies directly or through MCO contracts) a per member per month (PMPM) fee in addition to regular FFS payments for their Medicaid patients.2

In this year’s survey, 11 states reported having adopted or expanded PCMHs in FY 2016 and 13 states indicated plans to do so in FY 2017 (Table 11). A few of these states reported notable expansions. Wyoming, a state without MCO or PCCM programs, implemented PCMHs in FY 2015 and is expanding the number of practices participating in both FY 2016 and FY 2017. Idaho reported that its PCMH program expanded to its full PCCM network in FY 2016. In addition to the established PCMH programs administered by the three MCOs operating in Tennessee, a new, multi-payer PCMH initiative would begin in January 2017, starting with 20 to 30 practices. Alaska and Ohio are planning to implement new PCMH initiatives in FY 2017 and Pennsylvania’s new MCO contracts will encourage PCMHs beginning in FY 2017.

In contrast, Alabama expects a reduction in PCMHs in FY 2017 when the state begins contracting with MCOs. Maryland reported that an all-payer PCMH initiative sunsetted in December 2015; however, noted that Medicaid continued the program for an additional six months.

ACA Health Homes

Over one-third of states (20) had at least one Health Home initiative in place in FY 2015 (up from 16 states in FY 2014) (Table 10). This option, created under Section 2703 of the ACA, builds on the PCMH concept. By design, Health Homes must target beneficiaries who have at least two chronic conditions (or one and risk of a second, or a serious and persistent mental health condition), and provide a person-centered system of care that facilitates access to and coordination of the full array of primary and acute physical health services, behavioral health care, and social and long-term services and supports. This includes services such as comprehensive care management, referrals to community and social support services, and the use of health information technology (HIT) to link services, among others. States receive a 90 percent federal match rate for qualified Health Home service expenditures for the first eight quarters under each Health Home State Plan Amendment; states can (and have) created more than one Health Home program to target different populations.

In this survey, six states reported having adopted or expanded Health Homes in FY 2016 and seven states reported plans to do so in FY 2017 (Table 11). Of these six states, three reported new Health Home State Plan Amendments (SPAs) in FY 2016: two targeting persons with serious mental illness (SMI) (DC and New Mexico) and one targeting chronic conditions, implemented in primary care settings (Michigan). Four states plan to implement new Health Home SPAs in FY 2017: two targeting persons with SMI (Minnesota and Tennessee) and two targeting persons with multiple chronic conditions (California and DC). Also, Wyoming reported that Health Homes were under consideration for possible implementation in FY 2018.

Idaho reported ending their Health Home program in FY 2016. Two states (Alabama and Kansas) reported ending their Health Home programs in FY 2017. Alabama noted that its Health Home program would end in FY 2017 but would be encompassed in its Section 1115 waiver program establishing Regional Care Organizations.

Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs)

Seven states reported having ACOs in place for at least some of their Medicaid beneficiaries in FY 2015 (Table 10). While there is no uniform, commonly accepted federal definition of an ACO, an ACO generally refers to a group of health care providers or, in some cases, a regional entity that contracts with providers and/or health plans, that agrees to share responsibility for the health care delivery and outcomes for a defined population.3 An ACO that meets quality performance standards that have been set by the payer and achieves savings relative to a benchmark can share in the savings. States use different terminology in referring to their Medicaid ACO initiatives, such as Coordinated Care Organizations (CCOs) in Oregon and Regional Care Collaborative Organizations (RCCOs) in Colorado.4

In this survey, five states reported adopting or expanding ACOs in FY 2016 and 11 states reported plans to do so in FY 2017 (Table 11) – a significant increase over the three states in last year’s survey that reported new or expanded ACO initiatives in FY 2015. This includes seven states that have implemented or are planning to implement new ACO initiatives: Delaware, Massachusetts, Missouri, New Mexico, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Washington. Three of these states (Missouri, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island) reported that they were building provisions into their MCO contracts either encouraging or requiring their MCOs to contract with ACOs. Another three states with more mature ACO programs (Colorado, Maine, and Minnesota) reported expansions of those programs in both FY 2016 and FY 2017. Vermont, which currently has a shared savings program with two ACOs, reported plans to move to risk-based ACOs – that is, both shared savings and shared risk – in FY 2017, and also indicated that it was in negotiations for an all-payer ACO that would begin in January 2017. Washington reported that components of its ACO program for public employees may be offered to the Medicaid population in FY 2017. While not counted among the states implementing ACOs in this year’s report, Maryland reported that it is working on a stakeholder process to develop recommendations for ACOs.

One state (Iowa) reported eliminating its ACO program in FY 2016 when it was subsumed into the state’s recently launched Medicaid managed care program.

| Massachusetts ACO Pilot |

| In response to a state law requiring MassHealth to adopt alternative payment methodologies to promote more coordinated and efficient care, MassHealth is working to restructure its delivery system and payments within the next few years to transition from FFS care to integrated ACOs. The state plans to launch an ACO pilot by the end of CY 2016, with a full ACO roll-out planned for FY 2018. Through the renewal and renegotiation of its Section 1115 waiver (which expires June 30, 2017), MassHealth is proposing to implement a $1.8 billion Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) program that will be used to support ACOs, invest in behavioral health care and long-term services and supports community capacity, and address health-related social needs. Also, to encourage enrollment in either an ACO or MCO, the state’s waiver extension request proposes to eliminate or limit certain optional benefits available to PCCM enrollees (e.g., chiropractic services, orthotics, eye glasses, and hearing aids) and impose differential copayments (i.e., lower for ACO and MCO enrollees).5 |

Episode-of-Care Payment Initiatives

Unlike FFS reimbursement, where providers are paid separately for each service, or capitation, where a health plan receives a PMPM payment for each enrollee intended to cover the costs for all covered services, episode-of-care payment provides a set dollar amount for the care a patient receives in connection with a defined condition or health event (e.g., pregnancy and delivery, heart attack, or knee replacement). Episode-based payments usually involve payment for multiple services and providers, creating a financial incentive for physicians, hospitals and other providers to work together to improve patient care and manage costs. Two states (Arkansas and Tennessee) reported that they had episode-of-care payment initiatives in place in FY 2015 (Table 10). Both of these states also reported expansions of these initiatives in FY 2016 and planned for FY 2017, with Tennessee commenting that it had designed over 25 episodes of care since 2013.

One state (New Mexico) reported a new episode-of-care initiative in FY 2016 and four states (Ohio, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Washington) reported plans for new initiatives in FY 2017 (Table 11). Ohio reported that, in CY 2017, it will make actual reward payments for three defined episodes of care. Pennsylvania indicated that its new MCO contracts encourage MCOs to adopt value-based purchasing arrangements, including episodes of care; Rhode Island reported that it was looking at a bundled payment rate for Maternity/NICU care; and Washington reported that public employee bundled payment programs may be expanded to the Medicaid population as well. While not counted in this year’s report, Michigan, South Carolina and Wyoming reported that episode-of-care payment was under consideration for future implementation.

Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) Program

Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) programs, which are part of broader Section 1115 demonstration waiver programs, provide states with significant funding to support hospitals and other providers in changing how they provide care to Medicaid beneficiaries. DSRIP waivers are not grant programs – they are performance-based incentive programs. Originally, DSRIP initiatives were more narrowly focused on funding for safety-net hospitals and often grew out of negotiations between states and HHS over the appropriate way to finance hospital care. Now, however, they are used to promote far more sweeping payment and delivery system reforms.

The first DSRIP initiatives were approved and implemented in California and Texas in 2010, followed by New Jersey, Kansas, New Mexico, Massachusetts, and New York (Table 10).6

- Four states reported new or expanded DSRIP programs in place in FY 2016: California’s new “PRIME” program began in January 2016 with the state’s Section 1115 waiver renewal; Massachusetts’s “Delivery System Transformation Initiatives” (DSTI) program was extended through FY 2017 and hospitals are adding new projects;7 New Hampshire implemented a new DSRIP program focused on mental health and substance use disorder services, and New Mexico expanded its existing program.

- For FY 2017, Alabama, Arizona, and Washington reported plans to implement new DSRIP programs. Arizona’s 1115 demonstration waiver was approved; however, CMS noted in the approval that they would continue to work with Arizona on the delivery system reforms to integrate physical and behavioral health for children and adults and Medicaid beneficiaries leaving the justice system. On September 30, 2016, CMS issued a letter approving core facets of Washington’s waiver proposal subject to final approval of the special terms and conditions. Washington has committed under the waiver that 90 percent of its provider payments under state-financed health care (Medicaid and public employees) will be linked to quality and value by 2021. Massachusetts and New Mexico reported planned expansions of their existing programs (Table 11). Looking further into the future, Massachusetts reported that it was currently applying for a new five-year DSRIP waiver starting in FY 2018. Under the proposal, the Commonwealth’s current DSTI program would be restructured substantially.

Other Initiatives

In addition to the initiatives discussed already, states reported on a variety of other delivery system and payment reform initiatives. For example, two states (California and Connecticut) reported plans to implement shared savings arrangements or alternative payment methodologies for federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), and two states reported implementing “Health Home-like” programs, one for addressing opioid issues “Centers of Excellence” (Pennsylvania) and the other for behavioral health (Virginia). Two states (Oklahoma and Oregon) reported participating in the CMS Innovation Center’s Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative.8 Also, California reported on the transformation of its traditional Disproportionate Share Hospital funding program to a global budget structure for services provided to the uninsured, and Louisiana indicated plans to modernize its hospital reimbursement methods by converting from cost report-based per diem payment to value-based payment.

All-payer claims database (APCD) systems are large-scale databases that systematically collect medical claims, pharmacy claims, dental claims (typically, but not always), and eligibility and provider files from both private and public payers. APCD can be used to help identify areas to focus reform efforts and for other purposes. Eleven states (Colorado, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Maine, Minnesota, New Hampshire, Oregon, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Virginia, and Wisconsin) reported having APCDs in place in FY 2015. An additional state (Maryland) reported implementing an APCD in FY 2016, and four states (Delaware, Hawaii, Vermont, and Washington) reported plans to implement an APCD in FY 2017. New Mexico reported that planning was underway for the future implementation of an APCD.

Table 10: Delivery System and Payment Reform Initiatives in Place in all 50 States and DC, FY 2015

| States | Patient-Centered Medical Homes (PCMH) |

ACA Health Homes | Accountable Care Organizations (ACO) | Episode of Care Payments | Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment Program (DSRIP) | Other Initiatives | Any of these Initiatives in Place in FY 2015 |

| Alabama | X | X | X | ||||

| Alaska | |||||||

| Arizona | |||||||

| Arkansas | X | X | X | ||||

| California | X | X | |||||

| Colorado | X | X | X | ||||

| Connecticut | X | X | X | ||||

| Delaware | |||||||

| DC | |||||||

| Florida | X | X | |||||

| Georgia | |||||||

| Hawaii | |||||||

| Idaho | X | X | X | ||||

| Illinois | |||||||

| Indiana | |||||||

| Iowa | X | X | X | ||||

| Kansas | X | X | X | ||||

| Kentucky | |||||||

| Louisiana | X | X | |||||

| Maine | X | X | X | X | |||

| Maryland | X | X | X | ||||

| Massachusetts | X | X | X | ||||

| Michigan | X | X | X | ||||

| Minnesota | X | X | X | ||||

| Mississippi | |||||||

| Missouri | X | X | X | ||||

| Montana | X | X | |||||

| Nebraska | X | X | |||||

| Nevada | |||||||

| New Hampshire | |||||||

| New Jersey | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| New Mexico | X | X | X | ||||

| New York | X | X | X | X | |||

| North Carolina | X | X | X | ||||

| North Dakota | |||||||

| Ohio | X | X | |||||

| Oklahoma | X | X | X | X | |||

| Oregon | X | X | X | X | |||

| Pennsylvania | |||||||

| Rhode Island | X | X | X | ||||

| South Carolina | X | X | |||||

| South Dakota | X | X | |||||

| Tennessee | X | X | X | ||||

| Texas | X | X | X | ||||

| Utah | |||||||

| Vermont | X | X | X | X | |||

| Virginia | X | X | |||||

| Washington | X | X | |||||

| West Virginia | X | X | |||||

| Wisconsin | X | X | X | ||||

| Wyoming | X | X | |||||

| Totals | 29 | 20 | 7 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 36 |

| NOTES: “Other initiatives” – OK and OR reported participating in the CMS Innovation Center’s Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative. Oregon has a hospital quality incentive program that is “DSRIP-like” and is authorized under a Section 1115 waiver but is not counted here. SOURCE: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured Survey of Medicaid Officials in 50 states and DC conducted by Health Management Associates, October 2016. |

|||||||

Table 11: Delivery System and Payment Reform Actions Taken in All 50 States and DC, FY 2016 and FY 2017

| States | Patient-Centered Medical Homes (PCMH) |

ACA Health Homes | Accountable Care Organizations (ACO) | Episode of Care Payments | Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment Program (DSRIP) |

Other Initiatives | Any New or Expanded Initiative | |||||||

| 2016 | 2017 | 2016 | 2017 | 2016 | 2017 | 2016 | 2017 | 2016 | 2017 | 2016 | 2017 | 2016 | 2017 | |

| Alabama | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Alaska | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Arizona | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Arkansas | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| California | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Colorado | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Connecticut | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Delaware | X | X | ||||||||||||

| DC | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Florida | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Georgia | ||||||||||||||

| Hawaii | ||||||||||||||

| Idaho | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Illinois | ||||||||||||||

| Indiana | ||||||||||||||

| Iowa | ||||||||||||||

| Kansas | ||||||||||||||

| Kentucky | ||||||||||||||

| Louisiana | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Maine | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Maryland | ||||||||||||||

| Massachusetts | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Michigan | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Minnesota | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Mississippi | ||||||||||||||

| Missouri | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Montana | ||||||||||||||

| Nebraska | ||||||||||||||

| Nevada | ||||||||||||||

| New Hampshire | X | X | ||||||||||||

| New Jersey | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| New Mexico | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| New York | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| North Carolina | ||||||||||||||

| North Dakota | ||||||||||||||

| Ohio | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Oklahoma | ||||||||||||||

| Oregon | ||||||||||||||

| Pennsylvania | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Rhode Island | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| South Carolina | ||||||||||||||

| South Dakota | ||||||||||||||

| Tennessee | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Texas | ||||||||||||||

| Utah | ||||||||||||||

| Vermont | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Virginia | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Washington | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| West Virginia | ||||||||||||||

| Wisconsin | ||||||||||||||

| Wyoming | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Totals | 11 | 13 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 11 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 21 | 25 |

| NOTES: Expansions of existing initiatives include rollouts of existing initiatives to new areas or groups and significant increases in enrollment or providers. SOURCE: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured Survey of Medicaid Officials in 50 states and DC conducted by Health Management Associates, October 2016. |

||||||||||||||