Access to Dental Care in Medicaid: Spotlight on Nonelderly Adults

Introduction

Oral health is a critical but often overlooked component of overall health and well-being.1 Although good oral health can be achieved through preventive care, regular self-care, and the early detection, treatment, and management of problems, many people suffer from poor oral health, which often has additional adverse effects on their general health and quality of life.2 The prevalence of dental disease and tooth loss is disproportionately high among people with low income, reflecting lack of access to dental coverage and care. Racial and ethnic disparities in these measures are also pronounced.

Medicaid, the major health coverage program for low-income Americans, provides a uniquely comprehensive mandatory benefit package for children that includes oral health screening, diagnosis, and treatment services. In the last decade, with federal and state leadership, Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) have made important progress in addressing gaps in low-income children’s access to dental care, boosting children’s use of preventive and primary dental services. However, even with a robust benefit package, securing access to dental providers and services has remained a key challenge. The situation for low-income adults in Medicaid is more complex than that for children. Dental benefits for Medicaid adults are not required by federal law, but are offered at state option, and most states provide only limited coverage – in many cases, restricted to extractions or emergency services. Further, when states have faced budget pressures, adult dental services in Medicaid have typically been among their first cutbacks.3 It is noteworthy, too, that the Medicare program, which covers elderly adults and nonelderly adults with disabilities, provides no dental benefits.

Comprehensive coverage of dental care for children in Medicaid and CHIP, as well as the designation of pediatric dental care as one of the ten essential health benefits (EHB) under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), indicate recognition among policymakers of the importance of oral health. New opportunities now exist to establish similarly robust oral health benefits for low-income adults. Broad state flexibility to define Medicaid benefits for adults, the ACA expansion of Medicaid to nonelderly adults up to 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL), and Medicaid payment and delivery system reform are key policy levers. To help inform federal and state action concerning adult access to oral health care, this brief examines the oral health status of low-income adults, the dental benefits covered by state Medicaid programs, and low-income adults’ access to dental care today.

Why adult oral health is important

Untreated oral disease can have serious adverse impacts. Untreated oral health problems can affect appetite and the ability to eat, or lead to tooth loss, all of which can lead, in turn, to nutrition problems.4 Untreated problems can also cause chronic pain that can affect daily activities such as speech or sleep.5 Research has also identified associations between chronic oral infections and diabetes, heart and lung disease, stroke, and poor birth outcomes.6 Oral health problems can also interfere with work; employed adults are estimated to lose more than 164 million hours of work each year due to oral health problems or dental visits.7 Adults who work in lower-paying industries, such as customer service, lose two to four times more work hours due to oral health-related issues than adults who have professional positions.8 Visibly damaged teeth or tooth loss can also harm job prospects for adults seeking work.

Dental disease prevalence in nonelderly adults

Nationally, 27% of all adults age 20-64 have untreated dental caries, but the burden of disease is not distributed evenly in the population.9 The rate of untreated dental caries is highest (44%) among adults with income below 100% FPL ($11,880 per year for an individual in 2016) –more than twice the rate (17%) among adults with income at or above 200% FPL (Figure 1). Racial and ethnic minorities were also disproportionately affected by oral health problems. Both Black and Hispanic adults had significantly higher rates of untreated caries than Whites, largely a reflection of their higher rates of poverty.

Figure 1: Prevalence of Untreated Dental Caries Among Nonelderly Adults, by Income and Race/Ethnicity, 2011-2012

Medicaid’s role in covering low-income adults

In 2014, Medicaid covered nearly 28 million low-income nonelderly adults. The program covers 4 in every 10 nonelderly adults under the poverty level.10 As of February 2016, 31 states and DC had adopted the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) Medicaid expansion, which provides Medicaid eligibility to nearly all adults with income at or below 138% FPL ($16,394 per year for an individual in 2016); 19 states have not adopted the Medicaid expansion. The uninsured rate among low-income adults remains high, especially in non-expansion states.11 Across non-expansion states, the median Medicaid income eligibility for parents is 44% FPL, and adults without dependent children, except pregnant women and people with disabilities, are excluded from Medicaid no matter how poor they are. An estimated 2.9 million adults with income below 100% FPL fall into the “coverage gap” across non-expansion states – without access to Medicaid coverage and unable to qualify for subsidies in the Marketplace.12

Medicaid dental benefits for adults

States have considerable discretion in defining Medicaid adult dental benefits because these services are optional, not mandatory, under federal Medicaid law. Adult dental benefits are a state option across the board – for adults who qualify for Medicaid under pre-ACA law and also for adults newly eligible for Medicaid under the ACA expansion. States must provide Alternative Benefit Plans (ABPs) for Medicaid expansion adults, modeled on one of four “benchmark” options specified in the law, including an option for coverage approved by the HHS Secretary. All ABPs must include the ten essential health benefits (EHBs) established by the ACA.13 Notably, the EHBs include pediatric dental benefits, but not adult dental benefits.14 Many states have used the Secretary-approved coverage option to conform the benefits they provide for expansion adults with their benefits for adults in traditional Medicaid, modifying them as necessary to comply with the EHB requirements. Of the 31 states and DC that have adopted the Medicaid expansion, all but two states provide the same dental benefits for expansion adults that they do for the traditional adult Medicaid population. The two exceptions are Montana and North Dakota. Montana provides limited dental benefits for its traditional Medicaid adult population, but none for Medicaid expansion adults; North Dakota provides extensive dental benefits for traditional Medicaid adults, but none for expansion adults.

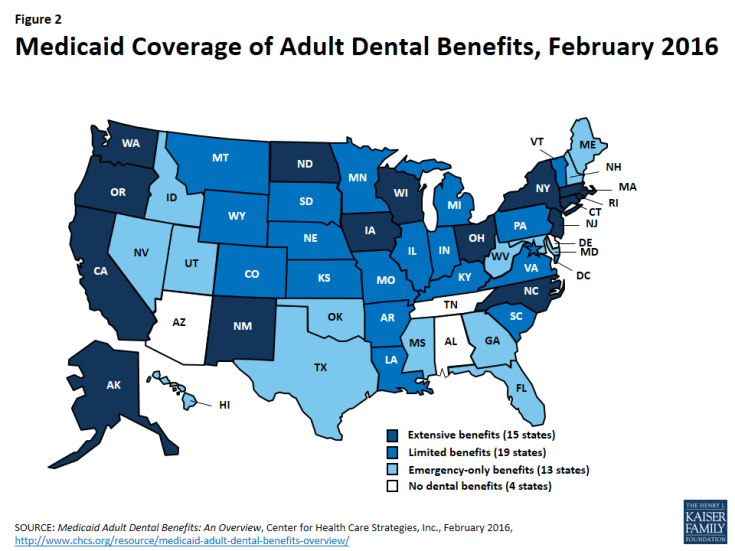

Almost all states (46) and DC currently provide some dental benefits for adults in Medicaid (Figure 2 and Appendix). However, just as commercial dental plans typically do, many state Medicaid programs set a maximum on their per-person spending for adult dental benefits or impose caps on the number of certain services they will cover. The scope of Medicaid adult dental benefits varies widely by state. As of February 2016, 15 states provided extensive adult dental benefits, defined as a comprehensive mix of services including more than 100 diagnostic, preventive, and minor and major restorative procedures, with a per-person annual expenditure cap of at least $1,000. Nineteen states provided limited dental benefits, defined as fewer than 100 such procedures, with a per-person annual expenditure cap of $1,000 or less. The remaining 13 states with any adult dental benefits covered only dental care for pain relief or emergency care for injuries, trauma, or extractions. Four states provided no dental benefits at all.15 Even in states that provide some dental benefits, adult Medicaid beneficiaries may face high out-of-pocket costs for dental care, making it difficult or impossible to afford.

As optional Medicaid services, adult dental benefits are also subject to being cut. Many states change their benefits from one year to the next. In particular, when states are under budget pressures, adult dental benefits in Medicaid have been cut back and, when their economies improve, states often move to restore them. For example, in 2009, California eliminated coverage of non-emergency dental services for adults. In 2014, the state restored many of the benefits, including preventive and restorative care, periodontal services, and dentures. Similarly, Illinois eliminated coverage of non-emergency dental services for adults in 2012, but expanded services again in 2014 to include limited fillings, root canals, dentures, and oral surgery services.16 Research has shown that when states reduce or eliminate adult dental benefits, unmet dental care needs increase, preventive dental service use decreases, and emergency department use for dental problems increases.17 18 19

Adult access to dental care

Access to and use of dental care among low-income adults depends on a number of variables. Medicaid eligibility for low-income adults, Medicaid coverage of dental benefits, the availability of dental providers, and beneficiary and provider awareness of the importance of preventive dental care all bear on whether low-income adults obtain dental services. Particularly in the absence of dental benefits, cost is the main barrier to access to dental care for low-income adults.20 Paying for services out-of-pocket is difficult, if not impossible, on their strained budgets. Over time, persistent lack of access to dental care or connection with dental providers may result in low expectations for oral health among low-income adults, reinforcing existing disparities. And if consumers are unaware of the need for regular checkups or cannot afford them, they may wait until they experience oral pain to seek care.

Dental Care Utilization and Unmet Need

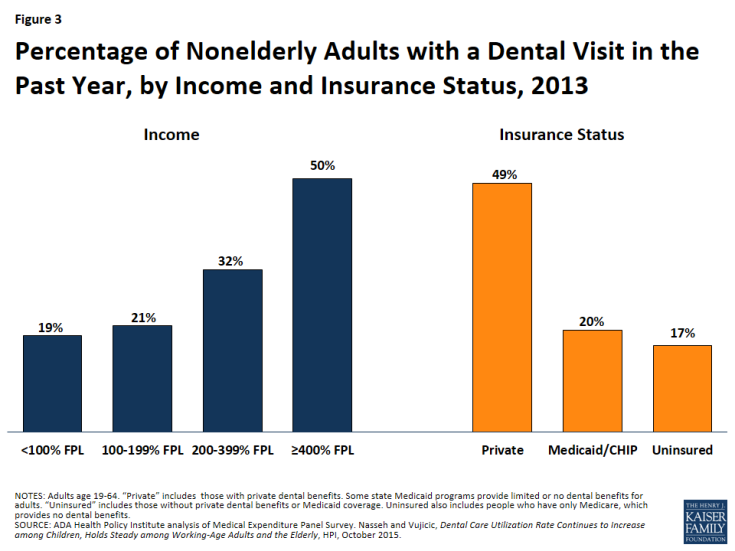

Regular dental care is important to maintaining good oral health. Low-income adults are less likely to have seen a dental provider within the last year than higher-income adults. In 2013, only about 1 in 5 adults with income below 200% FPL had a dental visit in the past year, compared to 1 in 3 of those with income of 200-399% FPL, and 1 in 2 adults with income above 400% FPL (Figure 3). Similarly, adults with private dental coverage were more than twice as likely as adults with Medicaid/CHIP or uninsured adults to have seen a dental provider within the last year. (Note: “Uninsured” includes adults without private dental benefits or Medicaid and nonelderly Medicare-only adults who do not have private supplemental dental benefits.) In 2013, 49% of adults with private coverage had a dental visit in the last year, compared to 20% of adults with Medicaid/CHIP and 17% of uninsured adults. Children in Medicaid/CHIP, for whom dental benefits are mandatory, were much more likely than adults in Medicaid to have had a dental visit (42%).21 The low visit rate for adults with Medicaid/CHIP coverage, compared to both children with Medicaid/CHIP and adults with private insurance, reflects, in part, the limited adult dental benefits covered in many state Medicaid programs.

Figure 3: Percentage of Nonelderly Adults with a Dental Visit in the Past Year, by Income and Insurance Status, 2013

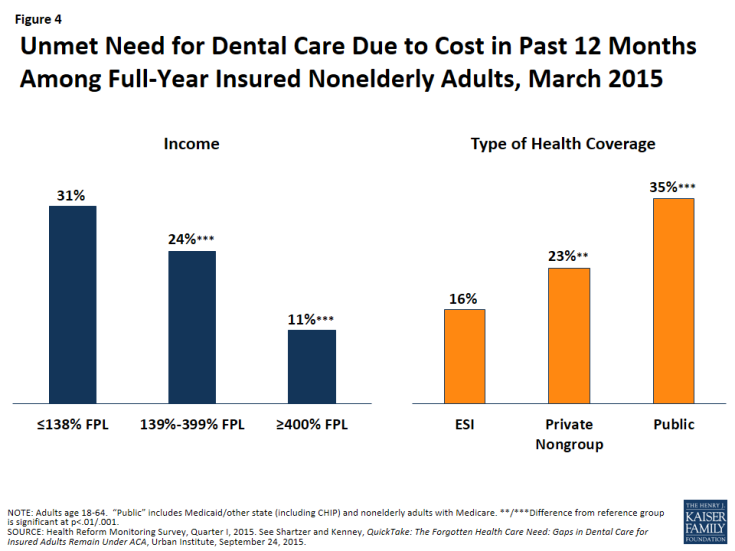

In recent research, dental care emerged as the service for which insured adults were most likely to report unmet need due to cost. This was especially true for low-income insured adults22 (Figure 4). Nearly one-third (31%) of full-year-insured nonelderly adults with income at or below 138% FPL and one-quarter (24%) of those between 139% and 399% FPL reported an unmet need for dental care due to cost, compared to 11% of full-year-insured adults with income at or above 400% FPL. Also, nonelderly adults with public insurance, including those with Medicaid/other state coverage and those with Medicare, were more than twice as likely to report an unmet need for dental care due to cost as adults with employer-sponsored insurance (35% vs. 16%) – again, likely reflecting limited Medicaid adult dental benefits in many states.

Figure 4: Unmet Need for Dental Care Due to Cost in Past 12 Months Among Full-Year Insured Nonelderly Adults, March 2015

Provider Availability and the Role of Health Centers

As of January 1, 2016, there were nearly 49 million people living in over 5,000 dental health professional shortage areas (HPSAs) across the country. HPSAs are defined primarily in terms of the number of dental health professionals relative to the population.23 Although there is some debate about whether a national shortage of dentists exists, most experts agree that there is a geographic maldistribution of dentists and a shortage of office-based dentists available to treat low-income and special needs populations, including people in nursing homes and other residential institutions. In addition, dentist participation in Medicaid is limited, as a large percentage of dentists accept no insurance and many dentists who do accept private insurance do not accept Medicaid.24 Medicaid beneficiaries often have difficulty finding a dental provider. The reasons dentists generally cite for not participating in Medicaid are low reimbursement rates, administrative burden, and high no-show rates among Medicaid patients.

Medicaid dental services may be delivered and paid for on a fee-for-service basis or by comprehensive or dental-only managed care plans that contract with the state. Of the 39 states with comprehensive Medicaid managed care in 2015, 29 states reported that they cover adult dental benefits. Of these states, 10 states reported carving-out adult dental benefits to Medicaid fee-for-service or prepaid health plans.25

Although most dental care is provided in solo or small office-based dental practices, community health centers are an important source of dental care for Medicaid beneficiaries and others in low-income, medically underserved communities. In 2014, health centers across the country served 22.5 million patients, a large majority of them Medicaid beneficiaries (46%) and uninsured patients (28%).26 The ACA made a major investment in health center growth, establishing a five-year $11 billion Health Center Trust Fund (which has since been extended through 2017), and providing $1.5 billion in new funding for the National Health Service Corps, which supplies many of the medical and dental providers who staff health centers. Health centers can also contract with private dental practices to provide oral health services to health center patients. Between the ACA trust fund dollars and increased patient revenues generated by expanded coverage for low-income people under the ACA, health centers in all states have been able to expand their service capacity; a recent survey of health centers found that those in Medicaid expansion states were significantly more likely than those in non-expansion states to have expanded their dental and mental services capacity since the start of 2014.27 In 2014, over three-quarters of health centers provided dental care, and about 15% of all health center patient visits were for dental services.28

One strategy with potential to increase access to dental care in low-income communities is to develop a more diverse oral health workforce, because minority providers are more likely to work in minority communities and to provide care to the underserved.29 Programs like the National Dental Pipeline Program have increased enrollment of under-represented minority students at participating dental schools. In addition, dental school accreditation standards have been revised to improve diversity among dental school faculty and students.30

Expanding the Supply of Dental Care: Scope-of-Practice & New Provider Types

In addition to dentists, dental hygienists, who specialize in preventive care and oral hygiene, are an integral part of the dental workforce. Dental hygienists work in a variety of settings (e.g., private offices, schools, nursing homes) in accordance with varying state requirements for dentist supervision, based on each state’s practice acts or regulations. To expand access to dental care, some states have amended their scope-of-practice rules to allow dental hygienists to furnish services without the presence or direct supervision of a dentist. Accompanying changes may be needed in some states’ Medicaid reimbursement policies and systems to permit dental hygienists to bill the program directly for services provided to Medicaid beneficiaries.

Some states have broadened the dental workforce further by introducing new midlevel dental provider types. Conceptually, midlevel dental providers play a role similar to that of nurse practitioners and physician assistants in the medical care context.31 They are part of the dental professional team and perform routine preventive and restorative services in a variety of settings.32 Three states – Alaska, Minnesota, and Maine – have recognized and licensed a new type of midlevel provider known as a dental therapist, to help improve access to care, especially for underserved populations. Education requirements, roles, and supervision requirements for midlevel dental providers vary across states. For example, Minnesota requires that at least 50% of the caseload of dental therapists and advanced dental therapists be Medicaid beneficiaries or underserved populations.33 Emerging research on midlevel dental providers indicates that they provide high-quality, cost-effective care.34

Other strategies for optimizing current dental care capacity are also developing. Effective January 1, 2015, California began requiring the Medicaid program to reimburse for services delivered by dental hygienists in consultation with remote dentists, a practice known as “teledentistry.”35 This law was passed years after the state began the Virtual Dental Home Demonstration Project, a pilot program designed to test the “virtual dental home” model to expand access to care in dental shortage areas. In this model, telehealth technology is used to link allied dental professionals working in the community – registered dental hygienists in alternative practice, registered dental hygienists, and registered dental assistants – with dentists located in dental offices or clinics. The community-based providers collect patient information, including medical histories and x-ray images, and this information is then sent to the collaborating dentist. A treatment plan is developed, and the community-based provider furnishes the services they are authorized to provide in the community, and patients requiring more complex services are referred to a local dentist.36

Dental Delivery System

Important changes in two key realms are poised to affect the delivery of dental care in the coming years. The first relates to the organization of service delivery. Movement toward more integrated, “whole-person” care and more accountable systems of care (e.g., Accountable Care Organizations) is leading to arrangements in which providers who have not traditionally done so are now sharing patient information and collaborating in care planning. Currently, states and delivery systems (e.g., managed care plans) are focused primarily on integrating behavioral health care with general medical care, but some systems are taking steps to integrate dental care as well.37 Interestingly, early research indicates that ACOs that provide dental services are more likely to include a health center and are much more likely to have contracts with Medicaid.38

The second realm of change is clinical care itself. A different paradigm for oral health care is emerging that departs from the traditional fee-for-service, procedure-driven model that prevails today, and instead involves care planning based on individual patient characteristics and risk factors, and payment tied to quality and outcomes, not volume.39 This approach is essentially a model of prevention and chronic care management, in which patient risk is assessed, and preventive care, early intervention, close monitoring, and care management are targeted to individuals with or at high risk for disease. The aim is to improve oral health outcomes by providing services based on individual patient risk and need. Rethinking systems of care and broad health system accountability may improve access to and utilization of dental care as well as the impact of Medicaid spending for dental services.

Looking ahead

Improving the oral health of low-income adults involves efforts to expand coverage, strengthen benefits, promote oral health, and improve access and care delivery. State Medicaid programs can play a major role in this area and have important levers for making advances. States that have not yet expanded Medicaid under the ACA have an opportunity to cover millions of poor adults who lack other affordable health coverage options. Independent of the Medicaid expansion, improving state economies may enhance the prospects for expansion of adult dental benefits in Medicaid programs. The progress that states have made in increasing children’s access to and use of dental care, by building stronger provider networks, leveraging accountability through contracts, and investing in care coordination efforts, provides a foundation for similar action for adults in Medicaid.40 States are also expanding the dental workforce by removing scope-of-practice barriers and through targeted efforts among dental schools to increase diversity among dental students, as under-represented minority students are more likely to provide care to the underserved. Finally, state Medicaid programs are implementing a host of payment and delivery reforms in pursuit of higher-quality care, better patient outcomes, and reduced costs. A central emphasis of these new approaches is more integrated care, sometimes encompassing an expanded range of health and social services and supports, as well as innovative workforce and other strategies for expanding access. With growing recognition that oral health is essential to overall health and well-being, these new models of care present potential for increasing access to dental care and improving dental care and outcomes for both children and adults in Medicaid.