Racial Disparities in Maternal and Infant Health: Current Status and Efforts to Address Them

NOTE: This brief was updated on November 4, 2024 to incorporate additional information about the role of midwives in maternal and infant care.

Summary

Stark racial disparities in maternal and infant health in the U.S. have persisted for decades despite continued advancements in medical care. The disparate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic for people of color increased attention to health disparities, including the longstanding inequities in maternal and infant health. Additionally, the overturning of Roe v. Wade, increased barriers to abortion and may widen the existing disparities in maternal health. Given these factors, there recently has been increased attention to improving maternal and infant health and reducing disparities in these areas.

This brief provides an overview of racial disparities for selected measures of maternal and infant health, discusses the factors that drive these disparities, and provides an overview of recent efforts to address them. It is based on KFF analysis of publicly available data from CDC WONDER online database, the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) National Vital Statistics Reports, and the CDC Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System. While this brief focuses on racial and ethnic disparities in maternal and infant health, wide disparities also exist across other dimensions, including income, education, age, and other characteristics. For example, there is significant variation in some of these measures across states and disparities between rural and urban communities. Data and research often assume cisgender identities and may not systematically account for people who are transgender and non-binary. In some cases, the data cited in this brief use cisgender labels to align with how measures have been defined in underlying data sources. Key takeaways include:

Large racial disparities in maternal and infant health outcomes persist. Pregnancy-related mortality rates among American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) and Black women are over three times higher than the rate for White women (63.4 and 55.9 vs. 18.1 per 100,000). Black, AIAN, and Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (NHPI) women also have higher shares of preterm births, low birthweight births, or births for which they received late or no prenatal care compared to White women. Infants born to Black, AIAN, and NHPI people have markedly higher mortality rates than those born to White people.

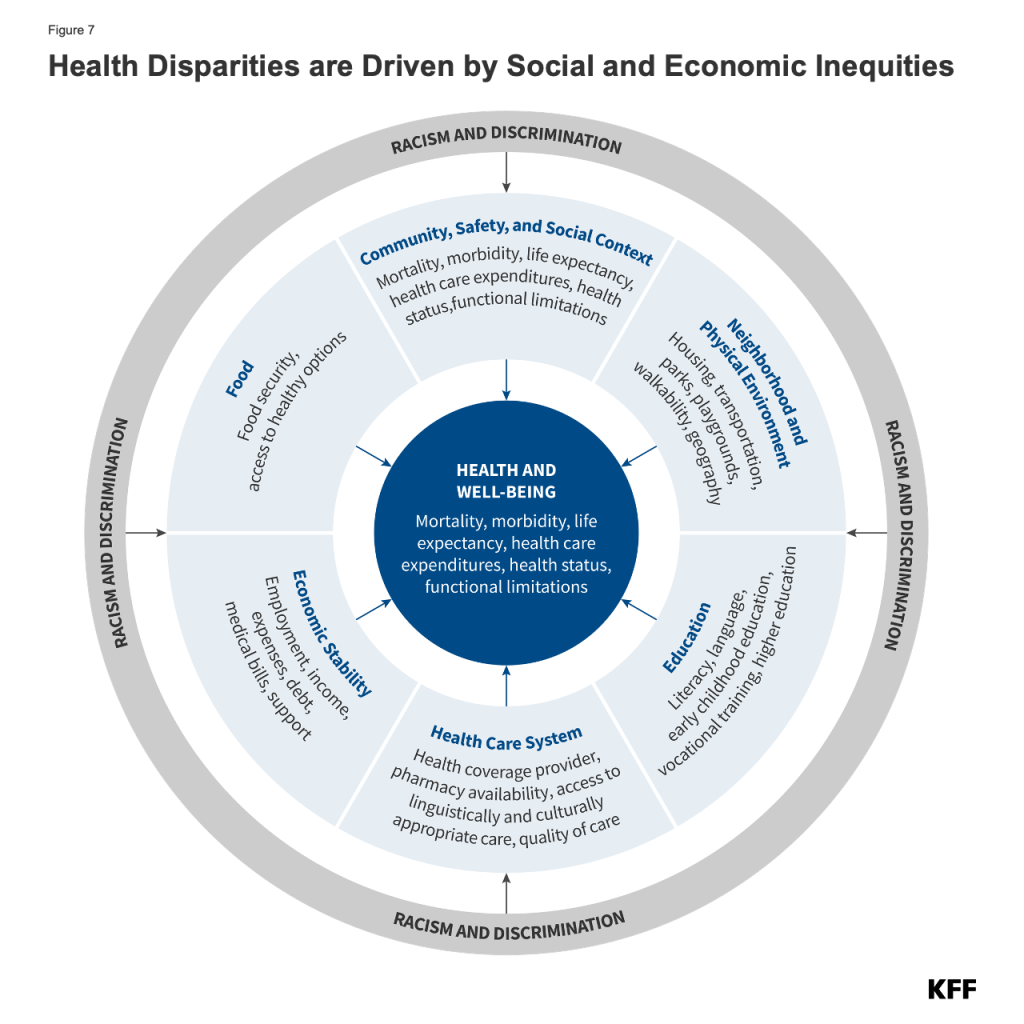

Maternal and infant health disparities reflect broader underlying social and economic inequities that are rooted in racism and discrimination. Differences in health insurance coverage and access to care play a role in driving worse maternal and infant health outcomes for people of color. However, inequities in broader social and economic factors, including income, are primary drivers for maternal and infant health disparities. Moreover, disparities in maternal and infant health persist even when controlling for certain underlying social and economic factors, such as education and income, pointing to the roles racism and discrimination play in driving disparities.

Increased attention to maternal and infant health has contributed to a rise in efforts and resources focused on improving health outcomes and reducing disparities in these areas. These include efforts to expand access to coverage and care, increase access to a broader array of services and providers that support maternal and infant health, diversify the health care workforce, and enhance data collection and reporting. However, addressing social and economic factors that contribute to poorer health outcomes and disparities will also be important. Moreover, the persistence of disparities in maternal health across income and education levels, points to the importance of addressing the roles of racism and discrimination as part of efforts to improve health and advance equity.

Moving forward, legislative and policy efforts and the outcome of the 2024 presidential election could all have important implications for efforts to address racial disparities in maternal and infant health. For example, state variation in access to abortion in the wake of the overturning of Roe v. Wade may exacerbate existing racial disparities in maternal health. Further, differences in records and proposed approaches by Vice President Harris and former President Trump on abortion, reproductive health, and maternal health will likely have different implications for disparities in maternal health going forward.

Racial Disparities in Maternal and Infant Health

Pregnancy-Related Mortality Rates

In 2020, approximately 900 women died in the U.S. from causes related to or worsened by pregnancy. Pregnancy-related deaths are deaths that occur within one year of pregnancy. Approximately one quarter (26%) occur during pregnancy, another quarter (27%) occur during labor or within the first week postpartum, and nearly half (47%) occur one week to one year postpartum, underscoring the importance of access to health care beyond the period of pregnancy. Recent data shows that more than eight out of ten (84%) pregnancy-related deaths are preventable. Although leading causes of pregnancy-related death vary by race and ethnicity, infection (including COVID-19) and cardiovascular conditions are the leading causes of pregnancy-related death among women overall, illustrating the importance of care for chronic conditions on pregnancy-related outcomes. Additional data from detailed maternal mortality reviews in 38 states found mental health conditions to be the overall leading cause of pregnancy-related deaths.

AIAN and Black people are more than three times as likely as White people to experience a pregnancy-related death (63.4 and 55.9 vs. 18.1 per 100,000 live births) in 2020 (Figure 1). Hispanic people also have a higher rate of pregnancy-related deaths compared to White people (22.6 vs. 18.1 per 100,000). The rate for Asian people is lower compared to that of White people (14.2 vs. 18.1 per 100,000). Data from one year were insufficient to identify mortality among NHPI women. However, earlier data showed that NHPI (62.8 per 100,000) people had the highest rates of pregnancy-related mortality across racial and ethnic groups.

Research shows that these disparities increase by age and persist across education and income levels. Data show higher pregnancy-related mortality rates among Black women who completed college education than among White women with the same educational attainment and White women with less than a high school diploma. Similarly, studies find that high income Black women have the same risk of dying in the first year following childbirth as the poorest White women. Other research also shows that Black women are at significantly higher risk for severe maternal morbidity, such as preeclampsia, which is significantly more common than maternal death. Further, AIAN, Black, NHPI, Asian, and Hispanic women have higher rates of admission to the intensive care unit during delivery compared to White women, which is considered a marker for severe maternal morbidity.

Maternal death rates declined across most racial and ethnic groups between 2021 and 2022 following the large increase in maternal deaths rates due to COVID-19. Maternal mortality and pregnancy-related mortality are similar concepts but maternal mortality is a narrower measure, limited to deaths that occur while pregnant or within 42 days or pregnancy and excluding those due to accidents or acts of violence. However, more recent maternal mortality data are available allowing for examination of trends since COVID-19. Black women had the highest maternal mortality rate across racial and ethnic groups between 2018 and 2022 and also experienced the largest increase during the pandemic (Figure 2). Maternal mortality rates decreased significantly across most racial and ethnic groups between 2021 and 2022. This decline may reflect a return to pre-pandemic levels following the large increase in maternal death rates due to COVID-19 related deaths. Despite this decline, the U.S. has the highest maternal mortality rate among high-income countries and the maternal mortality rate for Black women remained over two and a half times as high as the rate for White women.

Birth Risks and Outcomes

Black, AIAN, and NHPI women are more likely than White women to have certain birth risk factors that contribute to infant mortality and can have long-term consequences for the physical and cognitive health of children. Preterm birth (birth before 37 weeks gestation) and low birthweight (defined as a baby born less than 5.5 pounds) are some of the leading causes for infant mortality. Receiving pregnancy-related care late in a pregnancy (defined as starting in the third trimester) or not receiving any pregnancy-related care at all can also increase the risk of pregnancy complications. Black, AIAN, and NHPI women have higher shares of preterm births, low birthweight births, or births for which they received late or no prenatal care compared to White women (Figure 3). Notably, NHPI women are four times more likely than White women to begin receiving prenatal care in the third trimester or to receive no prenatal care at all (22% vs. 5%). Black women also are nearly twice as likely compared to White women to have a birth with late or no prenatal care compared to White women (10% vs. 5%).

While teen birth rates overall have declined over time, they are higher among Black, Hispanic, AIAN, and NHPI teens compared to their White counterparts (Figure 4). In contrast, the birth rate among Asian teens is lower than the rate for White teens. Many teen pregnancies are unplanned, and pregnant teens may be less likely to receive early and regular prenatal care. Teen pregnancy also is associated with increased risk of complications during pregnancy and delivery, including preterm birth. Teen pregnancy and childbirth can also have social and economic impacts on teen parents and their children, including disrupting educational completion for the parents and lower school achievement for the children. The drivers of teen pregnancy are multi-faceted and include poverty, history of adverse childhood events, and access to comprehensive education and health care services. Research studies have found that increased use of contraception as well as support for comprehensive sex education have helped lower the rate of teen births nationally.

Reflecting these increased risk factors, infants born to AIAN, Hispanic, Black, and NHPI women are at higher risk for mortality compared to those born to White women. Infant mortality is defined as the death of an infant within the first year of life, but most cases occur within the first month after birth. The primary causes of infant mortality are birth defects, preterm birth and low birthweight, sudden infant death syndrome, injuries, and maternal pregnancy complications. Infant mortality rates have declined over time although there was a slight increase between 2021 and 2022 (5.4 vs. 5.6 per 1,000 births, respectively). However, disparities in infant mortality have persisted and sometimes widened for over a century, particularly between Black and White infants. As of 2022, infants born to Black women are over twice as likely to die relative to those born to White women (10.9 vs. 4.5 per 1,000), and the mortality rate for infants born to AIAN and NHPI women (9.1 and 8.5 per 1,000) is nearly twice as high (Figure 5). The mortality rate for infants born to Hispanic mothers is similar to the rate for those born to White women (4.9 vs. 4.5 per 1,000), while infants born to Asian women have a lower mortality rate (3.5 per 1,000). Data also show that fetal death or stillbirths—that is, pregnancy loss after 20-week gestation—are more common among NHPI, Black and AIAN women compared to White and Hispanic women. Moreover, causes of stillbirth vary by race and ethnicity, with higher rates of stillbirth attributed to diabetes and maternal complications among Black women compared to White women.

About one in five AIAN, Asian or Pacific Islander, and Black women report symptoms of perinatal depression compared to about one in ten White women (Figure 6). Hispanic women (12%) have similar rates of perinatal depression compared to their White counterparts (11%). Other research shows that the prevalence of postpartum depression has grown dramatically over the course of the past decade increasing from 9.4% in 2010 to 19.3% in 2021, driven by increases among Black and Asian and Pacific Islander women. Women of color experience increased barriers to mental health care and resources, along with racism, trauma and cultural barriers. Research suggests that perinatal mental health conditions are a leading underlying cause of pregnancy-related deaths and that individuals with perinatal depression are also at increased risk of chronic health complications such as hypertension and diabetes. Infants of mothers with depression are more likely to be hospitalized and die within the first year of life.

Factors Driving Disparities in Maternal and Infant Health

The factors driving disparities in maternal and infant health are complex and multifactorial. They include differences in health insurance coverage and access to care. However, broader social and economic factors and structural and systemic racism and discrimination also play a major role (Figure 7). In maternal and infant health specifically, the intersection of race, gender, poverty, and other social factors shapes individuals’ experiences and outcomes. Recently there has been broader recognition of the principles of reproductive justice, which emphasize the role that the social determinants of health and other factors play in reproductive health for communities of color. Notably, Hispanic women and infants fare similarly to their White counterparts on many measures of maternal and infant health despite experiencing increased access barriers and social and economic challenges typically associated with poorer health outcomes. Research suggests that this finding, sometimes referred to as the Hispanic or Latino health paradox, in part, stems from variation in outcomes among subgroups of Hispanic people by origin, nativity, and race, with better outcomes for some groups, particularly recent immigrants to the U.S. However, the findings still are not fully understood.

Disparities in maternal and infant health, in part, reflect increased barriers to care for people of color. Research shows that coverage before, during, and after pregnancy facilitates access to care that supports healthy pregnancies, as well as positive maternal and infant outcomes after childbirth. Overall, people of color are more likely to be uninsured and face other barriers to care. Medicaid helps to fill these coverage gaps during pregnancy and for children, covering more than two-thirds of births to women who are Black or AIAN. However, AIAN, Hispanic, and Black people are at increased risk of being uninsured prior to their pregnancy, which can affect access to care before pregnancy and timely entry to prenatal care. Beyond health coverage, people of color face other increased barriers to care, including limited access to providers and hospitals and lack of access to culturally and linguistically appropriate care. Several areas of the country, particularly in the South have gaps in obstetrics providers. AIAN women also are more likely to live in communities with lower access to obstetric care. These challenges may be particularly pronounced in rural and medically underserved areas. For example, research suggests that closures of hospitals and obstetric units in rural areas has a disproportionate negative impact on Black infant health.

Research also highlights the role racism and discrimination play in driving racial disparities in maternal and infant health. Research has documented that social and economic factors, racism, and chronic stress contribute to poor maternal and infant health outcomes, including higher rates of perinatal depression and preterm birth among Black women and higher rates of mortality among Black infants. In recent years, research and news reports have raised attention to the effects of provider discrimination during pregnancy and delivery. News reporting and maternal mortality case reviews have called attention to a number of maternal and infant deaths and near misses among women of color where providers did not or were slow to listen to patients. A recent report determined that discrimination, defined as treating someone differently based on the class, group, or category they belong to due to biases, stereotypes, and prejudices, contributed to 30% of pregnancy-related deaths in 2020. In one study, Black and Hispanic women reported the highest rates of mistreatment (such as shouting and scolding, ignoring or refusing requests for help during the course of their pregnancy). Even controlling for insurance status, income, age, and severity of conditions, people of color are less likely to receive routine medical procedures and experience a lower quality of care. A 2023 KFF survey found that about one in five (21%) Black women say they have been treated unfairly by a health care provider or staff because of their racial or ethnic background. A similar share (22%) of Black women who have been pregnant or gave birth in the past ten years say they were refused pain medication they thought they needed.

Efforts to Address Maternal and Infant Health Disparities

Increased awareness and attention to maternal and infant health have contributed to a rise in efforts and resources focused on improving health maternal and infant health outcomes and reducing disparities. These include efforts to expand access to coverage and care, increase access to a broader array of services and providers that support maternal and infant health, diversify the health care workforce, and enhance data collection and reporting.

Since the launch of the White House Blueprint for Addressing the Maternal Health Crisis in 2022, there has been a variety of actions and investments across federal agencies to improve maternal health. The Biden-Harris Administration’s Blueprint focuses on increasing coverage for perinatal services, improving data collection and analysis, expanding the maternity workforce, strengthening social supports, and improving patient-provider relations. Federal initiatives have included a pilot project with distribution of newborn supply kits, a $27.5 million program for specialized maternity care training to over 2,000 OB/GYNs, nurses, and other providers. In March 2024, the Biden Administration issued a new Executive Order to advance women’s health research and innovation, including support to fund research to identify warning signs of maternal morbidity and mortality among Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) recipients. The Office of Intergovernmental and External Affairs (IEA) and the March of Dimes have created a public-private partnership, Maternal Health Collaborative to Advance Racial Equity, to improve maternal health outcomes among Black mothers. Additionally, the Biden-Harris Administration recently launched the Expanding Access to Women’s Health grant program, which will provide funding to 14 states and the District of Columbia to address disparities in maternal health outcomes with an emphasis on improving access to reproductive and maternal health coverage and services.

Nearly all states have expanded access to Medicaid coverage during the postpartum period, helping to stabilize coverage. Medicaid covers four in ten births nationally. However, historically, many pregnant women lost coverage at the end of a 60-day postpartum coverage period because eligibility levels are lower for parents than pregnant women in many states, particularly those that have not implemented the ACA Medicaid expansion. The American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) of 2021 initially provided states a new option to extend postpartum coverage to a full year beginning April 1, 2022. As of August 1, 2024, 47 states, including DC, had implemented a 12-month postpartum coverage extension, with additional states planning to implement the extension. KFF analysis suggests that the coverage extension could prevent hundreds of thousands of enrollees from losing coverage in the months after delivery. Additional actions to expand coverage may also help to reduce disparities, including adoption of the ACA Medicaid expansion in the ten remaining states that have not yet expanded, as nearly six in ten adults in the coverage gap in these states are adults of color, and Medicaid expansion promotes continuity of coverage in the prenatal and postpartum periods.

In addition, many state Medicaid programs have implemented policies, programs, and initiatives to improve maternity care and outcomes. This includes outreach and education to enrollees and providers about maternal health issues; expanding coverage for benefits such as doula care, home visits, and substance use disorder and mental health treatment; and using new payment, delivery, and performance measurement approaches. For example, Ohio’s Comprehensive Maternal Care program aims to develop community connections and culturally aligned supports for women with Medicaid as they and their families navigate pre- and post-natal care. Participating obstetrical practices are required to measure and engage with patients and families to hear firsthand accounts of how access to care, cultural competence, and communication methods affect patient outcomes. Some states also are leveraging managed care contracts to require Medicaid plans to develop an explicit focus on reducing disparities related to maternal and child health .

Implementation of evidence-based best practices may help to improve maternal and infant health outcomes. As part of its maternity care action plan, CMS has launched a “Birthing-Friendly” hospital designation to provide public information on hospitals that have implemented best practices in areas of health care quality, safety, and equity for pregnant and postpartum patients. Currently, more than 2,200 hospitals nationwide have received the “Birthing Friendly” designation, however, some argue that additional quality metrics and efforts are needed to improve the impact and utility of this designation. CMS is also proposing new baseline health and safety requirements for hospitals, including topics related to delivery of care in obstetric units, staffing, and annual training on evidence-based maternal health practice and cultural competencies. Moreover, in 2024, CMS has launched a new effort within its maternal and infant health initiative to focus on maternal mental health, substance use, and hypertension management.

Some states include a focus on equity as part of their Maternal Mortality Review Committee (MMRC). Nearly all states have an MMRC that reviews pregnancy associated deaths and offers recommendations to prevent future deaths. However, state MMRCs vary in how they examine racial disparities, with some specifying identifying and addressing disparities as a key focus. Beginning in 2020, discrimination was added to the list of circumstances surrounding a pregnancy-related death that can be reported by MMRCs. For example, in California, each death is examined through a health equity lens and considerations include how social determinants of health, discrimination, and racism may have contributed to the death. Similarly, Vermont amended the charge of its committee in 2020 to include considerations of disparities and social determinants of health, including race and ethnicity in perinatal death reviews. States also vary in the membership of their committees, with some having requirements related to Tribes and doulas or midwives. Washington, Montana and Arizona are examples of states that have a Native or Tribal Government representative, while Oregon and Louisiana have doula representation, and Vermont and Pennsylvania have midwife representation on their MMRCs.

A variety of efforts are underway to increase workforce diversity and expand access to doula services to improve maternal and infant health outcomes and reduce disparities. Studies have shown that a more diverse healthcare workforce and the use of midwives and doulas may improve birth outcomes. Midwives are an important component of the health care workforce, attending approximately one in ten births in 2021. Midwife-attended births are associated with fewer medical interventions, and there are efforts to grow and diversify the midwifery workforce to help improve maternal health outcomes and reduce mortality and morbidity.

The percent of maternal health physicians and registered nurses that are Hispanic or Black is lower than their share of the female population of childbearing age. The Biden Administration’s Blueprint includes efforts by HRSA to provide scholarships to students from underrepresented communities in health professions and nursing schools to grow and diversify the maternal care workforce.

Expanding access to doula services is another approach to increase diversity and expand the maternal health workforce. Doulas are trained non-clinicians who assist a pregnant person before, during and/or after childbirth by providing physical assistance, labor coaching, emotional support, and postpartum care. People who receive doula support have been found to have shorter labors and lower C-section rates, fewer birth complications, are more likely to initiate breastfeeding, and their infants are less likely to have low birth weights. The HHS FY2025 budget directs $5 million towards growing and diversifying the doula workforce and $5 million towards addressing emerging issues and social determinants of maternal health. Additionally, in recent years, there has been growing interest in expanding coverage of doula services through Medicaid. The MOMNIBUS is federal legislation that has been introduced to address maternal health disparities, and proposes to expand access to coverage of midwife and doula services. Some states are taking steps to include coverage through their state programs. As of early February 2024, 12 states reimburse services provided by doulas under Medicaid (CA, DC, FL, MD, MI, MN, NV, NJ, OK, OR, RI, VA), with two states, Louisiana and Rhode Island, also implementing private coverage of doula services. Some states also are seeking to increase access to these providers by providing patient education about these services, supporting training and credentialing of these providers, and raising reimbursement rates.

Some states are seeking to improve access to culturally responsive maternal and childcare through community engagement and collaboration with community stakeholders. For example, as part of its Birth Equity Project, Washington held listening sessions with Black, immigrant, and Indigenous families and birth workers to understand the challenges to birth equity in the state. In 2021 and 2022, Utah conducted the Embrace Project Study to reduce disparities among NHPI women by providing culturally responsive health services, with a focus on mental health and self-care practices rooted in ancestral NHPI cultural traditions. California has a Black Infant Health Program that includes empowerment-focused group support services and client-centered life planning to improve the health and social conditions for Black women and their families. Arizona hosts a maternal and infant mortality summit which brings together stakeholders to discuss how to improve equity and a Tribal maternal task force that develops a Tribal maternal health strategic plan and provides training about maternal health and family wellness from an Indigenous perspective.

A range of organizations are advocating for more interventions and support to address maternal mental health and substance use issues, major causes of pregnancy-related mortality and morbidity. Some studies have found higher rates of postpartum depression among some pregnant and postpartum women of color, but many mental health conditions are undiagnosed and untreated due to stigma and poor access to treatment. These issues also limit access to services for pregnant and postpartum people with substance use disorders. Additionally, some states have laws that take a punitive approach toward substance use during pregnancy, which may discourage some, particularly people of color, from seeking care. Community-based and provider organizations are calling for a number of policy and structural changes to address these challenges, including broader insurance coverage for behavioral health care, higher reimbursement for existing treatment services, greater education and awareness about screening for mental health and substance use conditions among health care providers and childbearing people. Federal initiatives in this area include the launch of the National Maternal Mental Health Hotline by HRSA to provide support, resources and referrals to new mothers and their families.

Looking Ahead

Improving maternal and infant health is key for preventing unnecessary illness and death and advancing overall population health. Healthy People 2030, which provides 10-year national health objectives, identifies the prevention of pregnancy complications and maternal deaths and improvement of women’s health before, during, and after pregnancy as a public health goal. Further, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Pathways to Prevention panel recently recommended a “maternal mortality moonshot” with a goal of reducing preventable maternal mortality by 50% and eliminating racial disparities within the next 10 years.

While there are a range of efforts underway to reduce disparities in maternal and infant health, state abortion bans and restrictions may exacerbate poor maternal and infant health outcomes and access to care. Since the Dobbs ruling in June 2022, about half of states have banned abortion or restricted it to early in pregnancy. People of color are disproportionately affected by these bans and restrictions as they are at higher risk for pregnancy-related mortality and morbidity, are more likely to obtain abortions, and more likely to face structural barriers that make it more difficult to travel out of state for an abortion. There are many documented cases of people being forced to continue pregnancies that are endangering their lives because they could not obtain abortion care, and the recent deaths of two pregnant women in Georgia were attributed directly to delays in pregnancy termination. State-level bans and restrictions criminalize clinicians who provide abortion care which also has cascading effects on other aspects of maternity care, and as a result some clinicians are choosing not to practice in these states, potentially widening existing clinician shortages. Research also suggests that rates of infant mortality have increased since the Dobbs ruling.

The outcome of the presidential election also could have important implications for disparities in maternal and infant health. While both candidates have taken actions focused on improving maternal health, former President Trump and Vice President Harris have widely differing records and proposals related to health coverage and health. Vice President Harris has been an outspoken advocate for eliminating maternal health disparities and promoting access to abortion and contraception services in addition to maternity care for all. Trump expresses his support for letting states set their own abortion policy, which can limit the availability of other related services, including maternity care.