State Medicaid Programs Respond to Meet COVID-19 Challenges: Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2020 and 2021

The coronavirus pandemic has generated both a public health crisis and an economic crisis, with major implications for Medicaid, a countercyclical program. During economic downturns, more people enroll in Medicaid, increasing program spending at the same time state tax revenues may be falling. As demand increases and state revenues decline, states face difficult budget decisions to meet balanced budget requirements. To help both support Medicaid and provide broad fiscal relief, the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA)1 authorized a 6.2 percentage point increase in the federal match rate (“FMAP”)2 (retroactive to January 1, 2020) available if states meet certain “maintenance of eligibility” (MOE) requirements.3 The fiscal relief is in place until the end of the quarter in which the Public Health Emergency (PHE) ends. The current PHE is in effect through January 21, 2021 which means the enhanced FMAP is slated to expire at the end of March 2021 unless the PHE is renewed.4

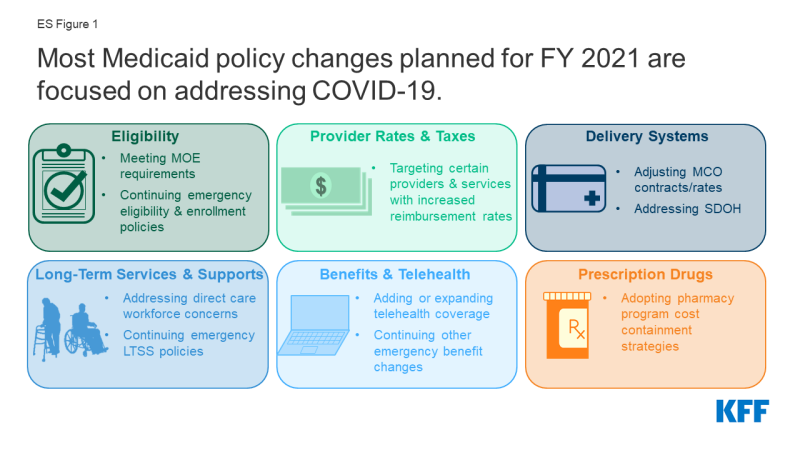

States ended state fiscal year (FY) 2020 and adopted budgets and policies for FY 2021, which began on July 1 for most states5, while faced with uncertainty about the pandemic, the economy, and the duration of the PHE. This report examines Medicaid policy trends with a focus on planned changes for FY 2021 based on data provided by state Medicaid directors as part of the 20th annual survey of Medicaid directors in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. Unlike previous years, the survey instrument was modified to primarily collect information about policy changes planned for FY 2021, especially policies related to responding to the pandemic. Overall, 43 states6 responded to the survey by mid-August 2020, although response rates for specific questions varied. Key findings suggest that most policy changes and issues identified for FY 2021 were related to responding to the COVID-19 PHE (Figure 1).

Eligibility and Enrollment

As part of the federal response to the COVID-19 pandemic, states meeting certain “maintenance of eligibility” (MOE) conditions can access enhanced federal Medicaid funding.7 In addition to meeting the MOE requirements,8 some states are utilizing Medicaid emergency authorities to adopt an array of actions to help people obtain and maintain coverage.9 While many states remained undecided, five states reported plans to continue COVID-19 related changes to eligibility and enrollment policies after the PHE ends, such as allowing self-attestation of certain eligibility criteria. States reported a variety of outreach efforts to publicize COVID-19 related eligibility and enrollment changes, and 10 states reported expanding enrollment assistance or member call center capacity during the PHE. At the time of survey submission, thirteen states had an approved State Plan Amendment (SPA) in place for the new Uninsured Coronavirus Testing group;10 however, this option that allows states to access a 100% federal match rate for coronavirus diagnostic testing expires at the end of the PHE.

Non-emergency eligibility changes were limited, except for plans to implement the Medicaid expansion. To date, 39 states (including DC) have adopted the ACA Medicaid expansion.11 Of these, 37 states have implemented expansion coverage (including Idaho and Utah, which both implemented the expansion on January 1, 2020, and Nebraska, which implemented the expansion as of October 1, 2020). Two additional states, Missouri and Oklahoma, will implement the expansion in FY 2022 as a result of successful Medicaid expansion ballot initiatives. Six states reported plans to implement more narrow eligibility expansions. Only a few states reported planned eligibility restrictions or plans to simplify enrollment processes in FY 2021.

Provider Rates and Taxes

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in financial strain for Medicaid providers, so unlike in prior economic downturns more states are implementing policies to provide targeted support to providers rather than rate cuts. At the time of the survey, more responding states implemented or were planning fee-for-service (FFS) rate increases relative to rate restrictions in both FY 2020 and FY 2021. More than half of responding states indicated that one or more payment changes made in FY 2020 or FY 2021 were related in whole or in part to COVID-19. Many states adopted FFS payment changes in FY 2020 and/or planned to make changes in FY 2021 to provide additional relief to providers in response to the PHE. Still, three states have cut provider rates across all or nearly all provider categories and other states have indicated rate freezes or reductions were likely. Historically, states tend to increase or impose new provider taxes during economic downturns; however, only one state reported the addition of a new provider tax in FY 2021 and few states reported making significant changes to their provider tax structure in FY 2021. Impacts of COVID-19 on provider tax collections and provider rates are still emerging.

Nearly half of states reported that federal provider relief funds were not adequate for Medicaid providers, while other states did not know at the time of the survey. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act and the Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act provide $175 billion in provider relief funds to reimburse eligible health care providers for health care related expenses or lost revenues that are attributable to the pandemic.12 Almost half of states responding to the survey reported that relief funds under the CARES Act have not been adequate to address the negative impact of COVID-19 faced by providers serving a high share of Medicaid and low-income patients.

Delivery Systems

Since nearly seven in ten Medicaid enrollees nationwide receive comprehensive acute care services (i.e., most hospital and physician services) through capitated managed care organizations (MCOs), these plans have played a critical role in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic.13 Twelve MCO states (of 31 responding) indicated plans to make adjustments to FY 2021 MCO contracts or rates in response to both COVID-related depressed utilization and unanticipated treatment costs. Fourteen MCO states (of 32 responding) reported implementing directed payments to selected provider types in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. MCO states reported a variety of programs, initiatives, or “value-added” services newly offered by MCOs in response to the PHE. Beyond addressing pandemic-related issues, twelve states in FY 2020 and seven in FY 2021 reported notable changes in the benefits and services covered under their MCO contracts.

The pandemic has elevated the importance of addressing social determinants of health (SDOH)14 to improve health and reduce longstanding disparities in health and health care. Nearly two-thirds of responding states reported implementation, expansion, or reform of a program or initiative to address Medicaid enrollees’ SDOH in response to COVID-19 (27 states).

Long-Term Services and Supports

The majority of responding states reported concerns about the pandemic’s impact on the long-term services and supports (LTSS) direct care workforce supply as well as concerns about access to personal protective equipment (PPE), access to COVID-19 testing, and risk of COVID-19 infections for LTSS direct care workers. Medicaid is the nation’s primary payer for LTSS.15 As the pandemic continues, states have taken a number of Medicaid policy actions to address the impact on seniors and people with disabilities who rely on LTSS to meet daily self-care and independent living needs.16 States noted plans to retain a variety of LTSS policy changes adopted in response to COVID-19 after the PHE period ends, most commonly citing the continuation of HCBS telehealth expansions.

Benefits, Cost-Sharing, and Telehealth

The majority of states added or expanded telehealth access in response to the pandemic, and many states plan to extend these and/or other benefit and cost-sharing changes beyond the PHE period. The majority of responding states report currently covering a range of FFS services delivered via telehealth when the originating site is the beneficiary’s home, most of which newly added or expanded this coverage in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Most states reported that services delivered via telehealth from the beneficiary’s home have payment parity as compared to services delivered face-to-face, and just over half of states planned to extend newly added/expanded FFS telehealth coverage beyond the PHE period, at least in part and at least for some services. Approximately one-third of responding states noted plans to extend other benefit and cost-sharing changes adopted during the PHE period (15 states); most of these are pharmacy changes. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, state changes to Medicaid benefits most commonly pertained to enhanced mental health and substance use disorder (SUD) services.17 Less than one-third of responding states reported plans to make benefit or cost-sharing changes that are not related to the PHE in FY 2021 (13 states).

Prescription Drugs

States continued to adopt pharmacy program cost containment strategies despite the COVID-19 emergency and other competing priorities. Managing the Medicaid prescription drug benefit and pharmacy expenditures remains a policy priority for state Medicaid programs, and state policymakers remain concerned about Medicaid prescription drug spending growth. Thirty-three responding states reported plans to newly implement or expand upon at least one initiative to contain prescription drug costs in FY 2021.

Challenges and Priorities

Nearly all states reported significant adverse economic and state budgetary impacts driven by the pandemic, as well as uncertainty about the future. In the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, states continue to encounter challenges to provide Medicaid coverage and access for a growing number of Americans, while also facing plummeting revenues and deepening state budget gaps. State Medicaid officials highlighted swift and effective state responses to the pandemic, such as the rapid expansion of telehealth, as well as ongoing efforts to advance delivery system reforms and to address health disparities and other public health challenges. In these ways, the pandemic has demonstrated how Medicaid can quickly evolve to address the nation’s most pressing health care challenges. However, the ability of states to sustain policies adopted in response to the pandemic (including through emergency authorities) may be tied to the duration of the PHE as well as the availability of additional federal fiscal relief and support. Looking ahead, great uncertainty remains regarding the future course of the pandemic, the scope and length of federal fiscal relief efforts, and what the “new normal” will be in terms of service provision and demand. Results of the November 2020 elections could also have significant implications for the direction of federal Medicaid policy in the years ahead.

Acknowledgements

Pulling together this report is a substantial effort, and the final product represents contributions from many people. The combined analytic team from KFF and Health Management Associates (HMA) would like to thank the state Medicaid directors and staff who participated in this effort. In a time of limited resources and challenging workloads, we truly appreciate the time and effort provided by these dedicated public servants to complete the survey and respond to our follow-up questions. Their work made this report possible. We also thank the leadership and staff at the National Association of Medicaid Directors (NAMD) for their collaboration on this survey. We offer special thanks to Jim McEvoy at HMA who developed and managed the survey database and whose work is invaluable to us.