COVID-19: Expected Implications for Medicaid and State Budgets

Robin Rudowitz

Published:

As new unemployment claims hit 6.6 million as of March 28th due to coronavirus – and a total of about 10 million over a two-week period – it will become increasingly important to monitor what happens to individuals who lose income and may qualify for Medicaid or become uninsured and what this means for state budgets.

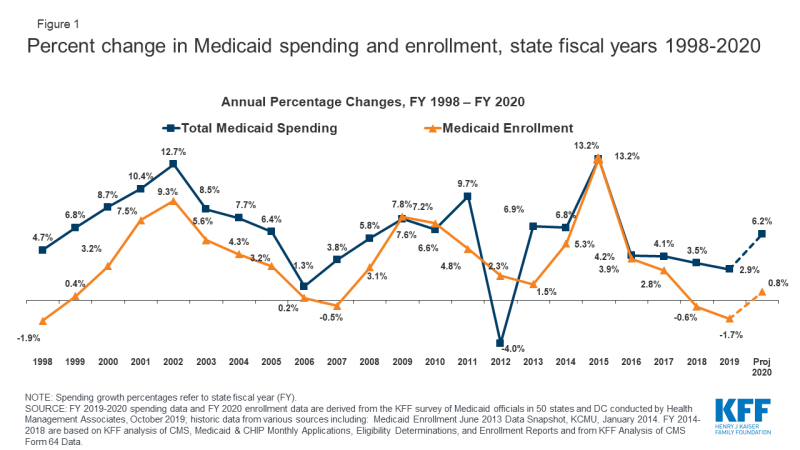

Medicaid is a countercyclical program, so during economic downturns more people lose income and will qualify for Medicaid. Medicaid spending is driven by multiple factors, including the number and mix of enrollees, medical cost inflation, utilization, and state policy choices. During economic downturns, enrollment in Medicaid grows. Looking back, we see peaks in Medicaid spending and enrollment growth in 2002 and 2009 due to recessions. The unemployment rate peaked at 10 percent in October 2009 during the Great Recession. Enrollment and spending also increased significantly following implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) as Medicaid coverage expanded, but have moderated in more recent years (Figure 1).

Large increases in the number of uninsured experienced in the Great Recession may not be repeated because of new coverage options under the ACA. Given large expansions in coverage for Medicaid adults through the ACA Medicaid expansion and subsidized coverage through the ACA marketplace, more individuals will qualify for coverage and fewer will likely become uninsured. In 37 states (including D.C.) that adopted the ACA Medicaid expansion, adults can qualify if their current income is up to 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL), or $1,467/month for individual, $3,013/month for a family of four. However, state unemployment benefits do count as income, so to the extent that individuals lose their jobs and qualify for unemployment compensation, they may remain over the Medicaid income limit until those benefits run out. The additional unemployment compensation in recent legislation to address COVID-19 is disregarded for Medicaid eligibility. In some expansion states, adults with higher incomes qualify, and in all states eligibility levels are higher for children and pregnant women. People can apply year-round, and services provided up to 3 months prior to application can be covered retroactively if you would have been eligible then. Under the ACA, beginning in January 2020, the federal government pays 90% of the costs for the expansion group, above the regular match rate in all states.

In non-expansion states, individuals will not have the same coverage options and more people may become uninsured. More than 2 million poor uninsured adults below poverty don’t qualify for Medicaid and fall into the coverage gap because they live in one of 14 states that have not yet adopted the ACA expansion. While people may lose jobs and income, more people will be eligible to receive expanded unemployment benefits included in the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act. People with incomes – including unemployment compensation – above the poverty level will qualify for subsidized coverage through the ACA marketplace.

States will experience large declines in revenue as needs for services, including Medicaid, grow. During the last recession, state revenues dropped significantly while spending growth continued, resulting in large budget gaps. Because states are required to balance their budgets, many states responded to the fiscal crisis by cutting spending. Most states enacted budget cuts to education, higher education, health programs, and state work force. Some states also increased revenues and relied on temporary measures such as borrowing, fund shifts, referred expenses, and asset sales. Some initial estimates show that states are already estimating share revenue declines and unemployment estimates could exceed those experienced in the last recession.

The current financing structure of Medicaid provides some protections for states facing higher Medicaid costs as a result of COVID-19 and changing economic conditions. The federal government jointly funds the Medicaid program with states by matching qualifying state Medicaid expenditures. When Medicaid spending rises during an economic downturn, these increased costs are shared by the federal government and there is no cap on available federal funds. Even with the federal match, states often turn to reductions in provider rates as well as cuts in some optional benefits. Often, these rates and benefits may be restored when economic conditions improve. States also frequently turn to greater reliance on provider taxes to help raise the state share of Medicaid during economic downturns. To the extent that more individuals qualify for the ACA Medicaid expansion group, those costs will receive the 90% ACA enhanced match.

Federal fiscal relief provided through the Medicaid FMAP during significant economic downturns has been successful in helping to support Medicaid and provide efficient and effective fiscal relief to states. To mitigate these budget pressures, Congress has twice passed temporary FMAP increases to help support states during economic downturns prior to the COVID-19 crisis, most recently in 2009 as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA). The ARRA-enhanced FMAP rates provided states over $100 billion in additional federal funds over 11 quarters, ending in June 2011. As a condition to receive the ARRA funds, states could not make eligibility or enrollment processes more restrictive. As a result of the ARRA-enhanced FMAP, state spending for Medicaid declined during the state fiscal years 2009 and 2010. The Families First Coronavirus Response Act included a temporary increase in the Medicaid FMAP from January 1, 2020 through the emergency period. The 6.2 percentage point increase does not apply to the expansion group. To be eligible for the funds, states cannot implement more restrictive eligibility standards or higher premiums than those in place as of January 1, 2020, must provide continuous eligibility for enrollees through the end of the month of the emergency period, and cannot impose cost sharing for COVID-19 related testing and treatment services including vaccines, specialized equipment, or therapies.

Looking ahead, the magnitude of the coverage changes as well as fiscal impact is expected to be even greater than the Great Recession. States could see increases in Medicaid enrollment and increases in costs for COVID-19 testing and treatment, at the same time that revenues are falling.