State Actions to Facilitate Access to Medicaid and CHIP Coverage in Response to COVID-19

Summary

As many people lose jobs and income due to the COVID-19 outbreak, a growing number will become eligible for Medicaid. To support states as enrollment in Medicaid grows and ensure enrollees maintain coverage, federal legislation provides states a temporary 6.2 percentage point increase in the federal matching rate and establishes conditions states must meet to access the enhanced funding. Beyond the conditions to access the enhanced funding, states can take a range of actions to expand Medicaid eligibility and make it easier for people to enroll. This brief summarizes state changes to Medicaid and CHIP eligibility and enrollment policies in response to the COVID-19 outbreak, beyond those required to access enhanced federal funding. It is based on KFF analysis of approved Medicaid and CHIP state plan amendments (SPAs) and information on state websites as of May 21, 2020.

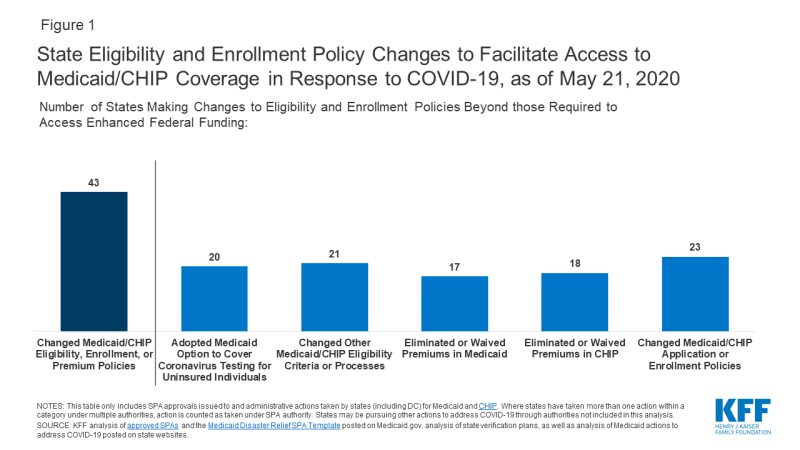

Overall, 43 states have made changes to facilitate access to Medicaid and/or CHIP coverage in response to the COVID-19 crisis, beyond those required to access enhanced federal funding. These include changes to expand eligibility or modify eligibility rules, eliminate or waive premiums, and streamline application and enrollment processes (Figure 1).

Figure 1: State Eligibility and Enrollment Policy Changes to Facilitate Access to Medicaid/CHIP Coverage in Response to COVID-19, as of May 21, 2020

Background

As many people lose jobs and income due to the COVID-19 outbreak, a growing number will become eligible for Medicaid. A recent KFF analysis shows that, by January 2021, when unemployment insurance benefits cease for most people who lost jobs between March 1 and May 2, 2020, nearly 17 million people could be newly eligible for Medicaid. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) has better positioned state Medicaid and CHIP programs to respond to an emergency such as the COVID-19 outbreak by expanding coverage in many states and establishing streamlined and modernized eligibility and enrollment systems across all states. However, there remains significant variation in eligibility and enrollment policies across states, and states still may face capacity issues as demand grows. To date, 37 states, including DC, have adopted the ACA Medicaid expansion to low-income adults, which will enable many more individuals to qualify for coverage as their incomes decrease.1 However, in the 14 states that have not adopted expansion, low-income adults will continue to face a coverage gap. All states have taken certain steps to streamline eligibility and enrollment under the ACA, but some states have taken up additional options to facilitate enrollment in coverage and the capacity of state eligibility and enrollment systems varies widely across states.2 Further, there are differences in eligibility and enrollment policies for children, pregnant women, parents and other adults compared to policies for people who qualify for age- or disability-based pathways (referred to non-MAGI groups), since some of the ACA simplifications did not extend to or remained optional for these groups.3

Federal legislation provides temporary enhanced federal Medicaid funding to states and establishes maintenance of eligibility requirements to access the funding. To help support states as enrollment in Medicaid grows and ensure existing enrollees maintain coverage, the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, as amended by the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, provides states with a temporary 6.2 percentage point increase in the regular federal matching rate for the emergency period. To receive the enhanced match states cannot implement more restrictive eligibility standards or higher premiums; must provide continuous eligibility for enrollees through the end of the month of the emergency period; and may not charge cost sharing for SARS-CoV-2 or COVID-19 related testing services or treatments.4,5 These provisions help ensure continuous coverage for existing Medicaid enrollees during the emergency period. However, they do not extend to children or pregnant women enrolled through CHIP.

Beyond the conditions to access the enhanced funding, states can take a range of actions to expand Medicaid eligibility and make it easier for people to enroll through existing state options and waivers. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services created a Medicaid Disaster Relief SPA as well as waiver templates to facilitate states’ ability to make program changes in response to COVID-19. States can also make changes through regular SPAs. Moreover, states can make some changes that do not require federal approval. Changes made through a disaster SPA or waiver are tied to the duration of the public health emergency period, which was extended at the end of April for an additional 90 days.

State Actions to Facilitate Access to Medicaid or CHIP

This brief summarizes changes states are making to Medicaid and CHIP eligibility and enrollment policies to facilitate access to coverage in response to the COVID-19 outbreak, beyond those required to access enhanced federal funding. It is based on KFF analysis of approved Medicaid and CHIP SPAs posted on Medicaid.gov, as well as analysis of state actions in response to COVID-19 posted on state websites and in verification plans as of May 20, 2020. States are continuing to take actions, and regularly updated information is available on the KFF Medicaid Emergency Authority Tracker. This analysis does not include changes to comply with the requirements to access enhanced federal funding or other changes states are making to Medicaid or CHIP programs, such as changes to benefits, cost sharing, or payment policies.

Overall, 43 states have taken action to facilitate access to Medicaid and/or CHIP coverage in response to the COVID-19 crisis, beyond those required to obtain enhanced federal funding (Figure 1). Among these, a number of states have taken multiple actions.

Eligibility Expansions and Other Eligibility Policy Changes

Optional Coverage of Coronavirus Testing for Uninsured Individuals. Twenty states have taken up the new optional Medicaid eligibility pathway that provides 100% federal matching funds for states to cover coronavirus testing and testing-related services for uninsured individuals, which was established by the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, as amended by the CARES Act.6

Twenty-one states have made other changes to eligibility criteria or processes, with some states making multiple changes. These actions include:

Other optional expansions. New Mexico has extended coverage to adults up to 200% FPL as part of their adult expansion group.

Changes to state residency criteria. Nine states are continuing eligibility for beneficiaries who have had to evacuate during the emergency or are temporarily out of state. Alaska and Washington are covering non-residents that are in the state temporarily.

Modifications to Eligibility Criteria for Non-MAGI Groups. States also have made changes to eligibility criteria for seniors and individuals that qualify for Medicaid on the basis of a disability to facilitate access to coverage. Five states (CA, IL, MO, WA, and VT) are applying less restrictive income or resource asset methodologies for these beneficiaries, who can be subject to income limits and asset tests as part of eligibility determinations.7 Missouri expanded coverage to adults who test positive for coronavirus by considering it a qualifying disability for its aged/blind/disabled pathway.8 Massachusetts is allowing people with disabilities whose eligibility is subject to a medical spend down to obtain a temporary hardship waiver of the spend down requirement during the public health emergency.

Allowing self-attestation of additional eligibility criteria. All states must verify citizenship or immigration status, as well as income, to determine Medicaid and CHIP eligibility.9 States can verify income prior to enrollment or enroll based on the applicant’s reported income and verify post-enrollment. For other eligibility criteria, including age/date of birth, state residency, and household size, states can verify this information before or after enrollment or accept an individual’s self-attestation. To expedite enrollment, states can allow for self-attestation for all eligibility criteria, excluding citizenship and immigration status, on a case-by-case for individuals subject to a disaster when documentation is not available.10 Thirteen states have taken up this option in response to COVID-19. In addition, Illinois and Ohio have increased their reasonable compatibility threshold, meaning the state has increased the difference between the amount of reported income and the amount identified through electronic data matches that it allows to determine an individual eligible.

Providing extended time to complete application or provide verification. Florida has extended the timeframe allowed to complete a Medicaid application, providing individuals more time to submit paperwork, while still using the initial application date as the basis for the start date for coverage. Further, eight states have extended the period they provide individuals to verify immigration status. States must verify immigration status prior to determining eligibility; however, they must give individuals who attest to a qualified status a reasonable amount of time to provide documentation.

Elimination or Waivers of Premiums

Seventeen states either eliminated or waived premiums in Medicaid as of May 21, 2020. Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, four states (CA, MD, MI, and VT) charged premiums to children in Medicaid, and six states (AR, IN, IA, MI, MT, WI) charged premiums or monthly contributions for adults in Medicaid. Three of these states (CA, MD, and VT) suspended premiums for children, and three states (IA, IN, and WI) eliminated premiums for other adult coverage groups in response to the COVID-19 outbreak. In addition, as of 2018, 34 of 45 states that offer a buy-in Medicaid program for working individuals with disabilities charged premiums, and some states charge premiums for children eligible through other disability-based eligibility pathways.11 A total of 16 states (AK, AZ, CA, CO, IA, ID, IL, IN, MD, ME, MN, NC, ND, WI, WY, and WA) report eliminating enrollment fees, premiums, or similar charges that apply to programs for people with disabilities in Medicaid in response to COVID-19, and one state (MO) has waived these premiums for individuals experiencing hardship due to COVID-19. Massachusetts had an existing waiver of premiums for individuals experiencing hardship; it has allowed individuals to self-attest to hardship in response to COVID-19. Under the requirements to access enhanced federal Medicaid funding, states must provide continuous eligibility through the end of the month in which the public health emergency ends. As such, even if a state has not eliminated or waived premiums, it cannot disenroll individuals due to unpaid premiums.

A total of 18 states report eliminating or waiving enrollment fees, premiums, or similar charges in CHIP. In addition, as noted above, Massachusetts had an existing premium hardship waiver, but has newly allowed individuals to self-attest to hardship in response to COVID-19. Prior to the outbreak, 26 of the 35 states with separate CHIP programs charged annual enrollment fees or monthly or quarterly premiums for children. Following this state action, most of these states have eliminated or waived premiums during the public health emergency. However, states vary in how they are implementing these changes and communicating them to enrollees. For example, some states are broadly communicating the change to families and suspending collection of payments, some are only waiving or suspending them for families experiencing hardship, and some are continuing to charge premiums but not disenrolling families due to nonpayment.

Streamlined Enrollment Processes

A total of 23 states have made changes to their Medicaid/CHIP enrollment and application processes as of May 21, 2020, with some states taking multiple actions. These changes include:

Expanded Use of Presumptive Eligibility. Presumptive eligibility (PE) is a longstanding option that allows states to authorize certain qualified entities, like community health centers or schools, to enroll individuals who appear likely eligible for coverage while the state processes the full application. Under the ACA, states were required to allow hospitals to conduct PE determinations regardless of whether the state had otherwise adopted the policy.12 As of January 2020, 31 states were using PE to expedite enrollment for one or more groups. A total of 6 (IL, KS, NE, NM, OR, and WA) of these 31 states have expanded use of PE to allow additional entities to determine PE as part of COVID-19 response, and two states (NE and IL) have extended presumptive eligibility to additional eligibility groups. In addition, seven states (CA, IA, MA, NM, UT, WA, and WI) have extended use of hospital PE determinations to non-MAGI eligibility groups.

Use of a Simplified Application. The ACA required all states to create a single streamlined application for Medicaid, CHIP, and Marketplace coverage and to provide options for individuals to apply for and renew coverage through multiple modes, including online and phone.13 In an emergency, states can adopt a simpler version of their paper or online application. Three states (AZ, KY, and WA) report adopting a simplified application option for Medicaid and/or CHIP to respond to the COVID-19 outbreak.

Promoting Continuity of Coverage. States must provide continuous coverage for Medicaid enrollees throughout the emergency period to receive enhanced federal funding; however, this requirement does not apply to children in CHIP. Some states have taken additional steps to promote continuity of coverage. As of January 2020, 32 states provided 12-month continuous eligibility to children in Medicaid or CHIP, enabling them to maintain coverage even if their households have small fluctuations in income. In response to COVID-19, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Rhode Island newly adopted continuous eligibility for children in Medicaid, and Arizona adopted continuous eligibility for children in both Medicaid and CHIP. In addition, Nebraska extended its continuous eligibility period for pregnant women covered through its unborn child option from six months through the end of the pregnancy period. Further, fourteen states (AZ, GA, IA, IL, KS, NC, NE, PA, RI, TN, UT, VA, WV, and WY) are delaying on acting on changes in circumstances or extending the redetermination period for CHIP populations to provide continuous coverage for enrollees, mirroring the requirements in Medicaid to receive enhanced funding.

Conclusion

In sum, states are taking a range of actions to facilitate access to Medicaid and CHIP coverage in response to COVID-19. Nearly all states (43) have made changes beyond what is required to access enhanced federal funding. The ACA has better positioned state Medicaid and CHIP programs to respond to an emergency such as the COVID-19 outbreak by expanding coverage in many states and establishing streamlined and modernized eligibility and enrollment systems across all states. However, there remains significant variation in eligibility and enrollment policies across states, and states still may face capacity issues as demand grows. The eligibility and enrollment changes states are making can mitigate challenges by enabling people to connect to coverage more quickly and easily and reducing administrative burdens for states. While these changes would increase enrollment and reduce the number of people uninsured, they would also increase state and federal spending for Medicaid coverage. Outside of eligibility and enrollment changes, states also are changing benefits, cost sharing and payment policies to facilitate access to care. Without certainty of additional federal support, many states will need to develop balanced budgets for the fiscal year beginning on July 1 (for most states) that could likely include significant spending cuts, including for Medicaid programs, at a time when demand for services is growing.