How Are States Supporting Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services During the COVID-19 Crisis?

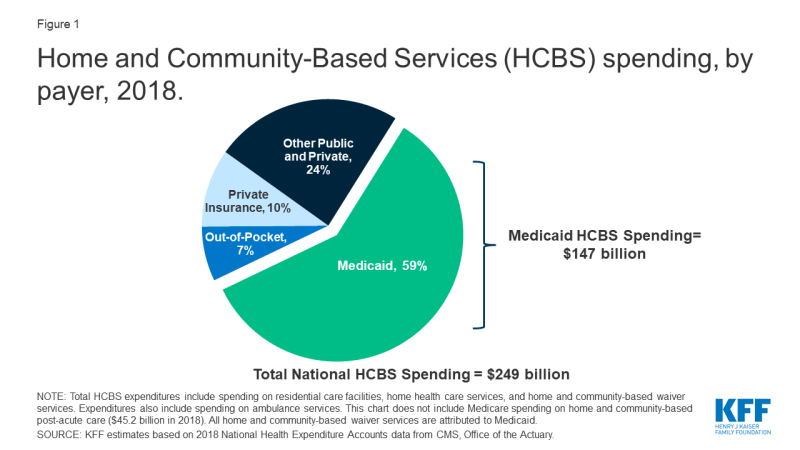

There has been a lot of focus on the impact of COVID-19 on people in nursing homes, but less attention so far paid to seniors and people with disabilities receiving long-term home and community-based services (HCBS), who also face serious issues. Some news reports recently have emerged about outbreaks in group homes for people with developmental disabilities and the impact on people who receive and those who provide home care. HCBS help with tasks such as bathing, dressing, and preparing meals. Medicaid is the primary payer for these services, financing 59% of HCBS (Figure 1). Over 2.5 million people received services through Medicaid HCBS waivers offered in all 50 states and DC in FY 2018. People receiving HCBS may be at increased risk of adverse health outcomes from COVID-19 due to older age and/or chronic illness as well as from unmet daily needs due to workforce and medical supply shortages during the crisis. Maintaining and potentially expanding HCBS during the public health emergency is critical to prevent increased need for nursing home care.

States are using a previously little-known Medicaid authority, Section 1915 (c) waiver Appendix K, to make temporary changes to their HCBS programs to respond to the COVID-19 emergency. States can use Appendix K to ensure that current HCBS enrollees continue to receive needed services, support providers, and cover additional people during the emergency. As of April 30, 2020, CMS has approved Appendix K authority in 182 waivers across 37 states.

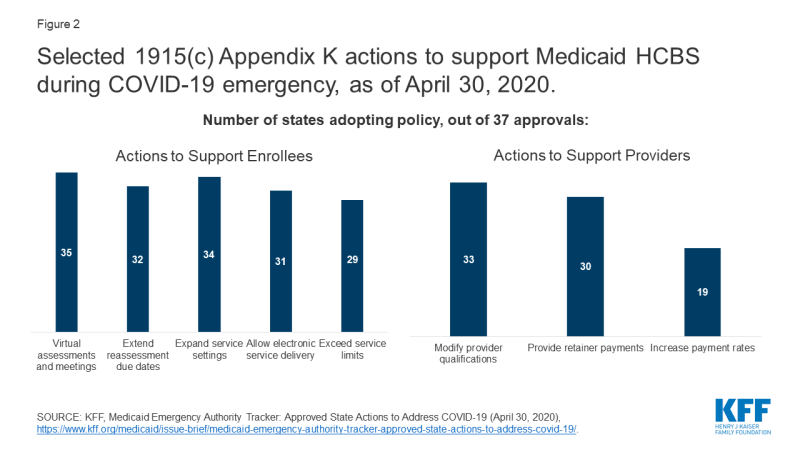

Most states with Appendix K approvals to date are temporarily adopting or modifying policies to ensure that current waiver participants remain enrolled in coverage and maintain access to services during the emergency (Figure 2). For example, nearly all Appendix K approvals allow virtual eligibility assessments and service planning meetings, and most extend due dates for eligibility reassessments. These changes are important to continuity of care and do not require substantial new funding. Similarly, many approvals permit remote services at home or otherwise expanding the settings where services can be provided to account for social distancing. Approvals also enable waiver enrollees to receive services beyond the typical limits when necessary to address health and welfare during the emergency. Fewer states are using Appendix K to add new services to the waiver benefit package, such as home-delivered meals, medical supplies or equipment, or services specific to the COVID-19 emergency, such as wellness counseling, changes which likely would require additional funding.

Figure 2: Selected 1915(c) Appendix K actions to support Medicaid HCBS during COVID-19 emergency, as of April 30, 2020

Many states with Appendix K approvals to date also are taking steps to support existing HCBS providers and expand the provider pool (Figure 2). For example, many approvals authorize making retainer payments to support the financial survival of providers who are temporarily unable to offer services as usual due to the crisis and temporarily modify provider qualifications to ensure an adequate workforce at a time when the health care system is strained to meet increased service needs and to account for providers who may be unable to work because they are ill. Like the most frequently adopted policy changes supporting enrollees, these actions do not require substantial new funding to implement. By contrast, fewer states are using Appendix K to temporarily increase provider payment rates to account for higher costs, such as personal protective equipment or hazard pay, during the emergency.

Few states with approvals to date are using Appendix K to serve more people in their HCBS waivers during the public health emergency. Many people on waiver waiting lists are at increased risk of coronavirus infection themselves or at increased risk of having unmet daily needs due to a caregiver’s infection. However, states are likely hesitant to commit additional funding as their budgets come under increased strain. Two states to date have temporarily increased the total number of people served under one of their waivers during the emergency (Maryland and Utah). A small number of states have temporarily increased cost limits or functional need criteria to expand the definition of who is eligible for the waiver during the emergency.

Overall, states’ use of Appendix K to temporarily adopt HCBS policies to respond to the COVID-19 emergency is limited, due to state budget constraints. The 6.2 percentage point increase in federal Medicaid matching funds recently enacted in the Families First Coronavirus Response Act is designed to help states facing increased costs during the emergency but likely is inadequate to encourage states to make even temporary changes during the emergency that require new funds. It remains to be seen whether additional legislative efforts will make more federal funding available to states to support current and expanded HCBS efforts to address the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.