Puerto Rico: Medicaid, Fiscal Issues and the Zika Challenge

The Commonwealth of Puerto Rico has been in the news spotlight for over a year due to the debt crisis that has followed a decade’s long recession, and to the rapid spread of Zika cases on the island, exceeding 19,000 as of September 21, 2016, and counting.1 Nearly half of the population (46%) in Puerto Rico lives below the federal poverty line, and the unemployment rate is more than double that of the 50 states and D.C. (12% vs. 5%).2,3 For a snapshot of Puerto Rico’s demographic characteristics, key health indicators, and a broader discussion of Zika on the island, see our 8 questions and answers about Puerto Rico fact sheet.

Roughly one in two Puerto Ricans (49%) are enrolled in the island’s Medicaid program, a rate more than double that of the 50 states and D.C. (19%).4 Puerto Rico provides Medicaid coverage through an island-wide public health insurance program, known as Mi Salud, the umbrella program for Puerto Rico’s Medicaid, CHIP, some Medicare, and some Puerto-Rico only funded coverage. The Puerto Rico Department of Health has a cooperative agreement with the Puerto Rico Health Insurance Administration (PRHIA), also known as the Administracion de Seguros de Salud (ASES), to administer Mi Salud.5 Puerto Rico’s Medicaid financing structure differs from that of the 50 states and D.C. in two important ways. First, federal funding to the program is subject to a statutory cap, and second, the island’s FMAP is fixed at 55% rather than being determined annually based on its per capita income. Under the ACA, Puerto Rico’s Medicaid program received increased federal funding through a $6.4 billion allotment as well as a modest increase in its federal match rate.

This fact sheet provides an overview of the Medicaid program in Puerto Rico and emerging fiscal issues facing its health care system as Zika cases on the island continue to mount.

Medicaid and the ACA in Puerto Rico

Financing

Unlike the 50 states and D.C., annual federal funding for Puerto Rico’s Medicaid program is subject to a statutory cap. Federal matching funds for Medicaid in the 50 states and D.C. are not capped. However, federal Medicaid funding in Puerto Rico and the other territories are subject to a statutory cap, meaning that once federal funds are exhausted, the island no longer receives financial support for its Medicaid program during that fiscal year. In 2014, the allotment was capped at $321 million, and the island generally exhausts its capped allotment prior to the end of its fiscal year.6

In addition, Puerto Rico’s federal match rate is fixed in federal statute. States and the federal government jointly finance the Medicaid program according to an established formula that provides guaranteed matching funds. In the 50 states, the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) is determined by a formula set in statute that relies on states’ relative per capita income. For federal fiscal year 2017, the FMAP ranges from a floor of 50% to a high of 75% for Mississippi, the poorest state in the country.7 Puerto Rico and the other territories receive a match rate that is fixed in statute and unrelated to per capita income. Before 2011, Puerto Rico and the other territories received the statutory minimum FMAP of 50% despite the fact that per capita income in 2014 was nearly half what it was in Mississippi ($11,331 vs. $21,036).8

The ACA increased Puerto Rico’s traditional match rate from 50% to 55%. For 2014 and 2015, the island also received an additional 2.2 percentage point increase to its FMAP for its non-expansion population, bringing it to 57.2% during those two years.9 The ACA provided Puerto Rico with the expansion state match rate for non-disabled adults without children. The expansion state FMAP for Puerto Rico was 78% in 2014 (Table 1).10

| Table 1: Changes to Puerto Rico FMAP under the ACA | |

| Match Rate | |

| Statutory Match Rate Pre-ACA | 50% |

| Statutory Match Rate Post-ACA | 55% |

| Special Match Rate for Non-Expansion Population in 2014-2015 | 57.2% |

| Match Rate for Childless Adults | Expansion State Match (78% in 2014) |

The ACA also made additional funds available to Puerto Rico, totaling nearly $6.4 billion. The $6.4 billion consists of a $5.5 billion allotment available between July 2011 and September 2019 and another $925 million the island received in lieu of funds it would have received for creating its own Marketplace. These funds are also available through FY 2019 and can only be accessed after the first source of ACA funding has been depleted. In 2014, the ACA funds accounted for the majority of federal Medicaid funds expended (68%) (Figure 1).11

Eligibility

Federal Medicaid eligibility and benefit rules are generally the same in Puerto Rico as in the 50 states and D.C. Medicaid requires Puerto Rico and the other territories to cover the same mandatory eligibility groups and benefits as the states, and allows them to cover the same optional eligibility groups and benefits. However, the island is not required to adhere to the federal poverty guidelines. Instead, the income-eligibility levels for Puerto Rico’s Medicaid program are based on a local poverty level that is established by the Commonwealth and approved by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).12

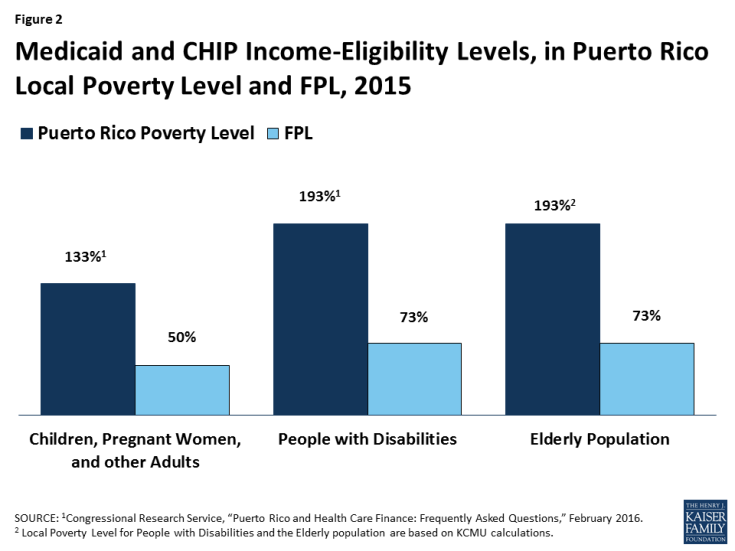

Prior to the ACA, Puerto Rico offered coverage to those with incomes up to at least 100% of the local poverty level. Even prior to the ACA Medicaid expansions, Puerto Rico covered all eligible populations with incomes up to at least 100% of the local poverty level,13 including non-disabled adults without children, an optional eligibility group. As of January 2014, Puerto Rico expanded Medicaid eligibility up to at least 133% of the local poverty level for children, pregnant women, parents and other adults with incomes up to at least 133% of the local poverty level. Elderly beneficiaries and those with disabilities are covered at roughly the same eligibility level as in the states (73% FPL) (Figure 2).14

Figure 2: Medicaid and CHIP Income-Eligibility Levels, in Puerto Rico Local Poverty Level and FPL, 2015

Benefits and Delivery System

Despite being subject to the same mandatory benefit requirements as the 50 states and D.C., Puerto Rico does not currently cover all mandatory Medicaid benefits. There has not been a comprehensive analysis of the benefits covered under Puerto Rico’s Medicaid program; however, several sources point to some services that are not covered by the program. For example, Puerto Rico currently lacks the infrastructure and funds necessary to offer long-term care in nursing facilities and home health services,15,16 and does not cover hospice care or medical equipment and supplies.17 In addition, limited benefits are provided to children under the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment (EPSDT) benefit.18

Puerto Rico’s Medicaid program provides acute, primary, and specialty services through a mandatory managed care delivery model. In Puerto Rico, Medicaid is delivered exclusively through a managed care model for most populations. The island contracts with one managed care program, Triple S, a licensee of the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association, and offers that coverage island-wide. Behavioral health services are carved-out and provided island-wide through a separate behavioral health managed care organization. Dual eligibles have the option to participate in a Medicare Advantage plan, called Medicare Platino, which provides Medicare acute and primary care and Medicaid wraparound services, and which together offer coverage equivalent to Mi Salud. Medicare Platino is offered through seven managed care plans, including four local plans (First Medical/First Plus, MCS, MMM Healthcare, and PMC Medicare Choice) and three national plans (Humana and two Blue Cross/Blue Shield affiliates—American Health Medicare and Triple S).19

Puerto Rico’s safety net providers play an important role in delivering health care to the island’s most vulnerable populations. In 2014, Puerto Rico had 20 federally-funded community health centers, with 71 sites across the island. These sites serve nearly 340,000 patients (roughly 10% of the population), 12% of whom are uninsured.20 However, the distribution of available clinical resources and health care professionals is focused in large metropolitan areas across the island, while the outlying communities and rural areas have limited access to care and treatment.21 Notably, Puerto Rico and the other territories are ineligible for Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) Subsidies, limiting the amount of resources available to the island’s safety net.22

Looking Ahead

ACA funding is estimated to be exhausted by the end of FY 2017. Puerto Rico has relied heavily on the nearly $6.5 billion in one-time ACA funds which were made available to the island in July 2011. While these funds are set to expire in September 2019, the island is expected to have exhausted them by the end of FY 2017.23 Absent reauthorization, up to 900,000 people (26% of the island’s population) could lose their health coverage.24

Inequities related to the island’s Medicaid finance structure, particularly the federal cap, have been acknowledged by various federal entities; however, no legislative action has been taken to date. The statutory cap on Puerto Rico’s Medicaid program combined with its low FMAP of 55% limits the island’s ability to offer certain mandatory Medicaid benefits and adds additional financial strain to its fragile economy. Acknowledging these difficulties, President Obama’s proposed budget for FY 2017 removed the cap and proposed gradually increasing the FMAP;25 however, this provision was not included in the final approved budget for FY 2017. Similarly, in August 2016, Treasury Secretary Lew and HHS Secretary Burwell sent a letter to the Congressional Task Force on Economic Growth in Puerto Rico urging Congress to remove the federal cap and increase the program’s FMAP. In the letter, the Secretaries stated that this proposed policy change, which has been analyzed for comparative effectiveness relative to other proposals, is one of the most powerful ways to support economic growth and long-term stability on the island.26 To date, no legislative action has been taken to reform the island’s Medicaid financing structure.

The number of Zika cases on the island continues to mount. In August 2016, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services declared the Zika outbreak in Puerto Rico a public health emergency, signaling the significant threat the virus poses to pregnant women and children born to infected pregnant women on the island. The declaration allows the Commonwealth to apply for funds to control the spread of Zika and request the temporary reassignment of local public health departments and personnel to assist in Zika response.27 President Obama’s emergency Zika funding request in February 2016 included a temporary one-year increase of approximately $250 million to Puerto Rico’s federal Medicaid matching funds, but no emergency Zika package has been passed by Congress to date.28 Financial constraints have complicated the timely and comprehensive response required to respond to the outbreak.29 Given the critical role Medicaid plays for people with disabilities, the serious and costly health effects of Zika in Puerto Rico may place further demands on a program already facing steep funding shortfalls. According to the CDC, the dollar amount of caring for a single child with birth defects is estimated to be in the millions.30

The debt crisis has exacerbated many of the island’s health care issues. As a result of the debt crisis, the government has instituted strict austerity plans that have led to budget cuts to public programs and more severe poverty.31 Delayed payments by the government to Medicare and Medicaid managed care plans have caused a cascade of payment delays to medical providers and suppliers, and there have been reports of power and water shortages in hospitals, delays in the arrival of medical supplies, the laying off of hospital workers, and the closure of hospital floors and service areas.32,33,34,35 The debt crisis has also contributed to health provider shortages, as specialists and subspecialists leave the island for better opportunities on the U.S. mainland,36,37,38 resulting in longer waits for procedures and overcrowded emergency rooms.39 After several months of congressional debate, the Puerto Rico rescue bill known as PROMESA was signed into law on June 30, 2016. The law places Puerto Rico’s fiscal affairs under a federal oversight board, allows for the restructuring of some of Puerto Rico’s debts, and includes a temporary stay on bondholder lawsuits.40 While the law represents a first step toward economic recovery, it does not address the critical issues facing Puerto Rico’s health care system, including the impending expiration of ACA funding, the limits imposed by the capped Medicaid financing structure, or the mounting cases and future consequences of Zika on the island.

Endnotes

The Kaiser Family Foundation State Health Facts. “Cases of Zika Virus Disease in the United States.” Data Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Zika virus disease in the United States, 2015-2016, as of Sept. 14, 2016.

Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of U.S. Census Bureau, 2014 American Community Survey, 1-Year estimates.

Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Regional and State Employment and Unemployment,” March 2016.

Kaiser Family Foundation estimates based on the Census Bureau’s 2014 American Community Survey, 1-year estimates.

“Puerto Rico Medicaid and CHIP Program Information,” CMS, accessed September 21, 2016, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid-chip-program-information/by-state/puerto-rico.html.

Annie Mach, Puerto Rico and Health Care Finance: FAQs, (Washington, D.C: Congressional Research Service, February 2016), https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R44275.pdf.

The District of Columbia is also subject to a statutorily set FMAP, which is 70%. The Kaiser Family Foundation State Health Facts. “Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) for Medicaid and Multiplier, FY 2017,” Data Source: FY 2017: Federal Register, November 25, 2015 (Vol 80, No. 227), pp 73779-73782. Accessed September 21, 2016.

U.S. Census Bureau; American Community Survey, 2014 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates, Table DP03; generated by Melissa Majerol; using American FactFinder, http://factfinder.census.gov/bkmk/table/1.0/en/ACS/14_1YR/DP03/0400000US28|0400000US72 (6 September 2016).

“Puerto Rico Medicaid and CHIP Program Information,” CMS, accessed September 21, 2016, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid-chip-program-information/by-state/puerto-rico.html.

Annie Mach, Puerto Rico and Health Care Finance: FAQs, (Washington, D.C: Congressional Research Service, February 2016), https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R44275.pdf.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Maria Portela and Benjamin D. Sommers, “On the Outskirts of National Health Reform: A Comparative Assessment of Health Insurance and Access to Care in Puerto Rico and the United States,” The Milbank Quarterly, 93 no. 3 (2015): 584-608, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4567854/.

Puerto Rico provides CHIP coverage to children in families with incomes up to 266% of the Puerto Rico poverty level, or 100% FPL for a family of three. Annie Mach, Puerto Rico and Health Care Finance: FAQs, (Washington, D.C: Congressional Research Service, February 2016), https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R44275.pdf.

“Puerto Rico, Information on How Statehood Would Potentially Affect Selected Federal Programs and Revenue Sources,” U.S. Government Accountability Office, Report to Congressional Requesters, March 2014, http://www.gao.gov/assets/670/661334.pdf.

Lew, J. and Burwell, S., U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Jacob J. Lew and U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Sylvia M. Burwell to The Honorable Senator Orrin Hatch, August 26, 2016. Letter. From U.S. Department of the Treasury, (accessed September 21, 2016), https://www.treasury.gov/connect/blog/Pages/Secretary-Lew-and-Secretary-Burwell-Send-Letter-to-Congressional-Task-Force-on-Economic-Growth-in-Puerto-Rico.aspx.

“Managed Care in Puerto Rico,” CMS, accessed September 21, 2016, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid-chip-program-information/by-topics/delivery-systems/managed-care/downloads/puerto-rico-mcp.pdf.

“Report by the President’s Task Force on Puerto Rico’s Status,” The White House, March 11, 2011, https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/uploads/Puerto_Rico_Task_Force_Report.pdf

“Managed Care in Puerto Rico,” CMS, accessed September 21, 2016, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid-chip-program-information/by-topics/delivery-systems/managed-care/downloads/puerto-rico-mcp.pdf.

Peter Shin, Jessica Sharac, Marie Nina Luis, and Sara Rosenbaum, Puerto Rico’s Community Health Centers in a Time of Crisis, (Washington, DC: The George Washington University, Milken Institute School of Public Health, Department of Health Policy and Management, Dec 2015), https://publichealth.gwu.edu/sites/default/files/downloads/GGRCHN/Policy%20Research%20Brief%2043.pdf.

“Report by the President’s Task Force on Puerto Rico’s Status,” The White House, March 11, 2011, https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/uploads/Puerto_Rico_Task_Force_Report.pdf

Annie Mach, Puerto Rico and Health Care Finance: FAQs, (Washington, D.C: Congressional Research Service, February 2016), https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R44275.pdf.

“HHS FY 2017 Budget in Brief-CMS-Medicaid,” CMS, accessed May 25, 2016.

Lew, J. and Burwell, S., U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Jacob J. Lew and U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Sylvia M. Burwell to The Honorable Senator Orrin Hatch, August 26, 2016. Letter. From U.S. Department of the Treasury, (accessed September 21, 2016), https://www.treasury.gov/connect/blog/Pages/Secretary-Lew-and-Secretary-Burwell-Send-Letter-to-Congressional-Task-Force-on-Economic-Growth-in-Puerto-Rico.aspx.

“President’s HHS FY 2017 Budget Factsheet,” HHS accessed September 21, 2016, http://www.hhs.gov/about/budget/fy2017/budget-factsheet/index.html.

Lew, J. and Burwell, S., U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Jacob J. Lew and U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Sylvia M. Burwell to The Honorable Senator Orrin Hatch, August 26, 2016. Letter. From U.S. Department of the Treasury, (accessed September 21, 2016), https://www.treasury.gov/connect/blog/Pages/Secretary-Lew-and-Secretary-Burwell-Send-Letter-to-Congressional-Task-Force-on-Economic-Growth-in-Puerto-Rico.aspx.

“HHS declares a public health emergency in Puerto Rico in response to Zika outbreak,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), August 12, 2016, accessed September 21, 2016, https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2016/08/12/hhs-declares-public-health-emergency-in-puerto-rico-in-response-to-zika-outbreak.html

“Fact Sheet: Preparing for and Responding to the Zika Virus at Home and Abroad,” The White House, February 8, 2016, accessed September 21, 2016, https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2016/02/08/fact-sheet-preparing-and-responding-zika-virus-home-and-abroad.

Lew, J. and Burwell, S., U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Jacob J. Lew and U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Sylvia M. Burwell to The Honorable Senator Orrin Hatch, August 26, 2016. Letter. From U.S. Department of the Treasury, (accessed September 21, 2016), https://www.treasury.gov/connect/blog/Pages/Secretary-Lew-and-Secretary-Burwell-Send-Letter-to-Congressional-Task-Force-on-Economic-Growth-in-Puerto-Rico.aspx.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Transcript for CDC Telebriefing: Zika Summit Press Conference, April 1, 2016, http://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2016/t0404-zika-summit.html

Peter Shin, Jessica Sharac, Marie Nina Luis, and Sara Rosenbaum, Puerto Rico’s Community Health Centers in a Time of Crisis, (Washington, DC: The George Washington University, Milken Institute School of Public Health, Department of Health Policy and Management, Dec 2015), https://publichealth.gwu.edu/sites/default/files/downloads/GGRCHN/Policy%20Research%20Brief%2043.pdf.

Nick Timiraos, “Treasury Secretary Jacob Lew Tours Puerto Rico to Urge Action in Congress,” Wall Street Journal (May 9, 2016), http://www.wsj.com/articles/treasury-secretary-jacob-lew-tours-puerto-rico-to-urge-action-in-congress-1462814534

Vann R. Newkirk II, “Will Puerto Rico’s Debt Crisis Spark a Humanitarian Disaster?” The Atlantic, (May 9, 2016), http://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2016/05/puerto-rico-treasury-visit/482562/.

Lizette Alvarez and Abby Goodnough, “Puerto Ricans Brace for Crisis in Health Care,” New York Times (August 2, 2015), http://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/03/us/health-providers-brace-for-more-cuts-to-medicare-in-puerto-rico.html.

Lew, J. and Burwell, S., U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Jacob J. Lew and U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Sylvia M. Burwell to The Honorable Senator Orrin Hatch, August 26, 2016. Letter. From U.S. Department of the Treasury, (accessed September 21, 2016), https://www.treasury.gov/connect/blog/Pages/Secretary-Lew-and-Secretary-Burwell-Send-Letter-to-Congressional-Task-Force-on-Economic-Growth-in-Puerto-Rico.aspx.

Pedro R. Pierluisi, Re: Formal Comment Letter on Proposed Rule (CMS-1590-P), (September 4, 2012), http://www.colegiomedicopr.org/docs/9.4.12%20Rep%20Pierluisi%20(PR)%20Comment%20Letter%20on%202013%20Physician%20Fee%20Schedule%20Proposed%20Rule.pdf.

Gretchen Sierra-Zorita, “Puerto Rico’s Unseen Crisis,” CNN (May 10, 2016), http://www.cnn.com/2016/05/10/opinions/puerto-rico-health-crisis-gretchen-sierra-zorita/.

Greg Allen, “SOS: Puerto Rico Is Losing Doctors, Leaving Patients Stranded,” (March 12, 2016), http://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2016/03/12/469974138/sos-puerto-rico-is-losing-doctors-leaving-patients-stranded.

Peter Shin, Jessica Sharac, Marie Nina Luis, and Sara Rosenbaum, Puerto Rico’s Community Health Centers in a Time of Crisis, (Washington, DC: The George Washington University, Milken Institute School of Public Health, Department of Health Policy and Management, Dec 2015), https://publichealth.gwu.edu/sites/default/files/downloads/GGRCHN/Policy%20Research%20Brief%2043.pdf.

S. 2328-PROMESA, 114th Congress (2015-2016), Public Law No: 114-187 (June 30, 2016), https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/4900.