Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility, Enrollment, Renewal, and Cost-Sharing Policies as of January 2016: Findings from a 50-State Survey

Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility

The ACA established a new minimum Medicaid eligibility level of 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL) for children, pregnant women, parents and non-disabled adults as of January 2014. This new minimum increased eligibility for parents in many states and provided a new eligibility pathway for other non-disabled adults who were largely excluded from Medicaid prior to the ACA. Although the expansion to adults with incomes up to 138% FPL was effectively made a state option by the Supreme Court’s 2012 ruling on the constitutionality of the ACA, the Court’s decision did not impact other eligibility changes in the law. As a result of the new 138% FPL minimum for children in Medicaid, some states moved certain children from CHIP to Medicaid. Moreover, all states implemented the ACA change to determine financial eligibility for Medicaid for children, pregnant women, parents, and non-disabled adults and CHIP based on Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI). This change created alignment with the method used for determining eligibility for subsidies to purchase Marketplace coverage. States continue to determine eligibility for other groups, such as individuals with disabilities and elderly individuals, based on previous non-MAGI-based rules.

The findings below show Medicaid and CHIP eligibility levels for children, pregnant women, parents, and other non-disabled adults as of January 2016 and identify changes in eligibility that occurred between January 2015 and January 2016. These data show that Medicaid and CHIP continue to be central sources of coverage for the nation’s low-income children and pregnant women, with some states adopting optional policies in 2015 that expand access to coverage for certain children and pregnant women. They also highlight the continued growth of Medicaid’s role for low-income adults through the ACA Medicaid expansion.

Children and Pregnant Women

Coverage for children in Medicaid and CHIP remains strong and steady with median eligibility at 255% FPL. Under the ACA’s maintenance of effort protections, states cannot make reductions in children’s eligibility through 2019. Reflecting this protection, there were no policy changes to children’s eligibility in 2015. However, in Kansas, the state’s CHIP eligibility level is tied to the 2008 FPL; thus, CHIP eligibility declined from 247% to 244% FPL and will continue to erode over time. As of January 2016, 48 states cover children with incomes up to at least 200% FPL through Medicaid and CHIP, including 19 states that cover children at or above 300% FPL (Figure 4). Across states, the upper Medicaid/CHIP eligibility limit for children ranges from 152% FPL in Arizona to 405% FPL in New York.

Mirroring previous action taken by California and New Hampshire in 2014, Michigan transitioned all children from its separate CHIP program into Medicaid as of January 2016. In contrast, Arkansas established a new separate CHIP program and moved children with family incomes from 147% to 216% FPL from its CHIP-funded Medicaid expansion to the new separate CHIP program. Enrollment remains open in all states with separate CHIP programs except in Arizona. Arizona froze enrollment in its separate CHIP program at the end of 2009, prior to enactment of the ACA eligibility protections.

States continued to take up options to enhance children’s access to coverage during 2015.

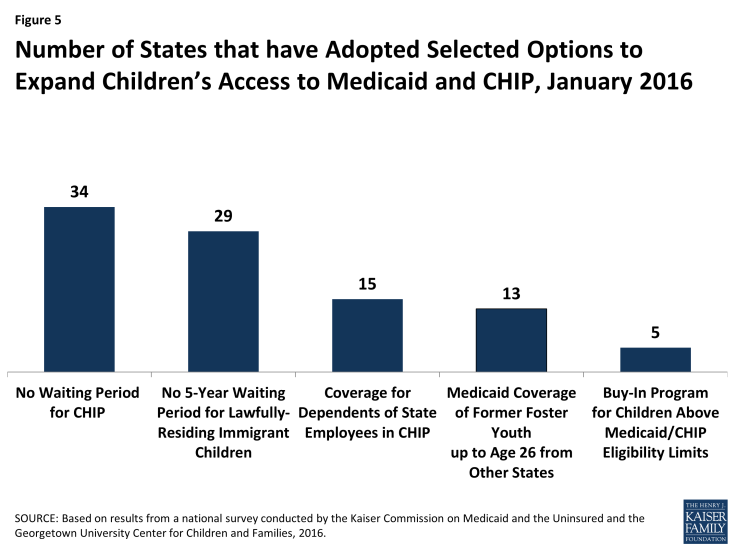

- Eliminating waiting periods for CHIP coverage. During 2015, Wisconsin eliminated its waiting period for its separate CHIP program. In addition, Michigan’s CHIP waiting period was eliminated when it transitioned all children from its separate CHIP program to Medicaid. With these changes, 24 states have eliminated waiting periods for CHIP since the ACA was enacted in 2010. As of January 2016, 34 states do not have a waiting period for CHIP coverage (Figure 5). However, 16 of the 36 states with separate CHIP programs have a waiting period that requires a child to be uninsured for a period of time prior to enrolling. These waiting periods may not exceed 90 days.

Figure 5: Number of States that have Adopted Selected Options to Expand Children’s Access to Medicaid and CHIP, January 2016

- Expanding coverage to recent lawfully residing immigrant children. With the addition of Colorado during 2015, 29 states have taken up the option to eliminate the five-year waiting period for lawfully present immigrant children in Medicaid and/or CHIP as of January 2016. In addition, six states (California, District of Columbia, Illinois, Massachusetts, New York, and Washington) use state-only funds to cover some income-eligible children regardless of immigration status.1 This count includes California, which has some local programs that cover children regardless of immigration status and recently passed legislation to cover children regardless of immigration status on a statewide basis starting in 2016.

- Expanding federally-funded CHIP coverage to dependents of state employees. As of January 2016, 2 additional states (Nevada and Virginia) took up the option to cover otherwise eligible children of state employees in a separate CHIP program, bringing the total number of states that have taken up this option to 15.

- Expanding coverage for former foster youth. Under the ACA, all states must provide Medicaid coverage to youth who were in foster care in the state up to age 26, but it is a state option to extend this coverage to former foster youth from other states. During 2015, New Mexico took up this option, raising the total number of states covering former foster youth from other states to 13 as of January 2016.

Following a trend since enactment of the ACA, the number of states offering buy-in programs for children in families above Medicaid or CHIP income limits continued to decline. States may offer buy-in programs to allow families with incomes above the upper limit for children’s coverage to buy-in to Medicaid or CHIP for their children. In 2015, North Carolina lifted the income limit on its buy-in program, while Connecticut eliminated its buy-in program. The number of states offering buy-in programs has declined from a peak of 15 in 2011 to 5 as of January 2016, reflecting that families above Medicaid and CHIP income thresholds may have new coverage options available through the Marketplaces.

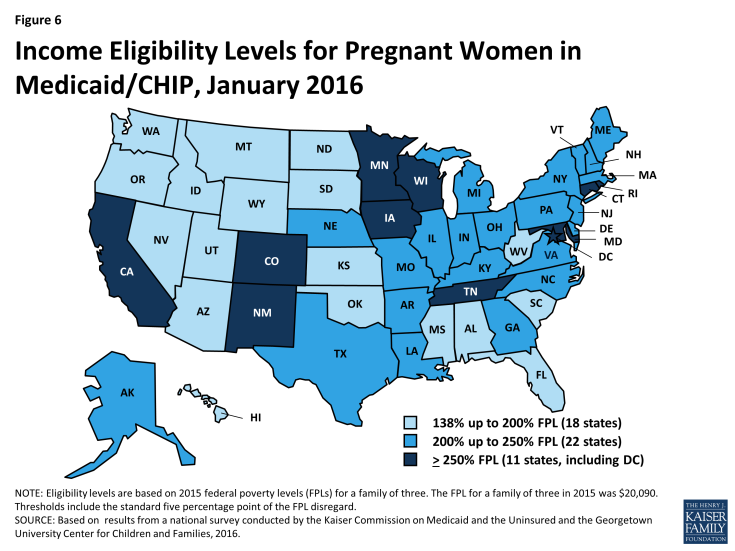

Coverage for pregnant women remained stable in 2015. The median eligibility level for pregnant women in Medicaid or CHIP held steady at 205% FPL, with eligibility ranging from 138% FPL in Idaho and South Dakota to 380% FPL in Iowa. Overall, 33 states cover pregnant women with incomes up to at least 200% FPL (Figure 6). The number of states that have eliminated the five-year waiting period for lawfully residing immigrant pregnant women in Medicaid and/or CHIP remained constant at 23. However, Colorado, which had previously covered recent lawfully-residing pregnant women in Medicaid, expanded this option to pregnant women in CHIP during 2015. The number of states covering income-eligible pregnant women regardless of immigration status through the CHIP unborn child option (15 states) or with state-only funds (3 states) remained unchanged.

Parents and Adults

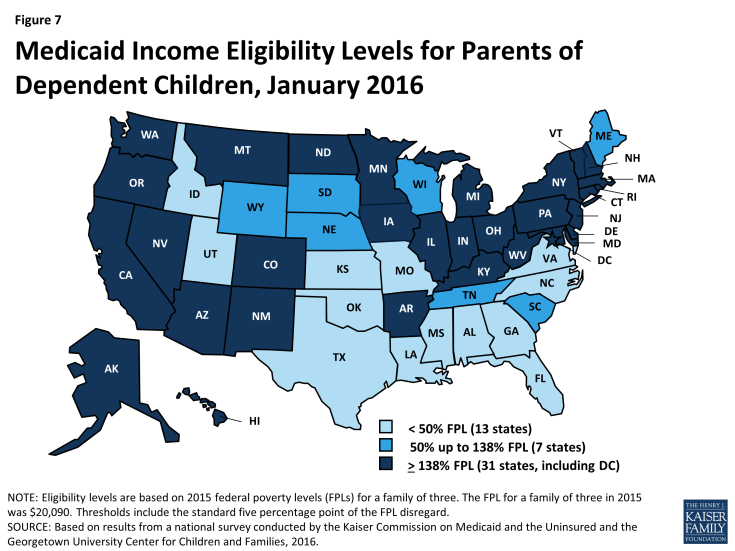

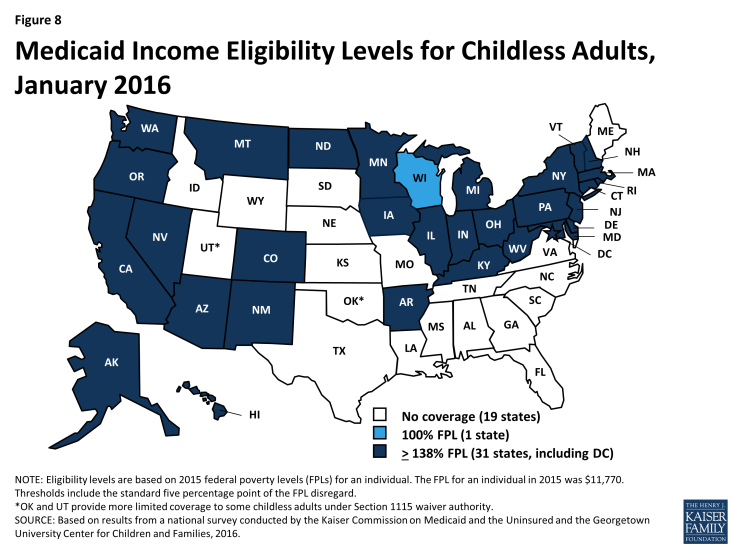

As of January 2016, 31 states, including the District of Columbia, have expanded Medicaid eligibility to parents and other non-disabled adults2 with incomes up to at least 138% FPL. This finding reflects adoption of the ACA Medicaid expansion to low-income adults in three states during 2015–Indiana, Alaska, and, most recently, Montana, where the expansion went into effect on January 1, 2016. Indiana and Montana joined four other states (Arkansas, Iowa, Michigan, and New Hampshire) that expanded Medicaid for adults under Section 1115 waiver authority, allowing them to implement the expansion in ways that extend beyond the flexibility provided by the law.3 During 2015, Pennsylvania moved from implementing its expansion through a waiver to regular expansion coverage, while New Hampshire moved from a regular expansion to a waiver as of January 2016. There is no deadline for states to adopt the Medicaid expansion, and additional states may expand in the future. Medicaid eligibility extends to parents and other adults with incomes up to at least 138% FPL in all 31 expansion states (Figures 7 and 8). Additionally, the District of Columbia covers parents up to 221% FPL and other adults up to 215% FPL. Connecticut reduced parent eligibility during 2015, lowering eligibility from 201% to 155% FPL. However, parent eligibility remains above the 138% FPL minimum, and many parents who lost Medicaid eligibility are likely eligible for subsidies to purchase Marketplace coverage.

As of January 2016, two states—Minnesota and New York—have implemented Basic Health Programs. The ACA provides an option for states to create a Basic Health Program (BHP) for low-income residents with incomes between 138% and 200% FPL, who would otherwise be eligible to purchase Marketplace coverage. Through this option, states provide alternative coverage that may cover more services or be more affordable than what is offered through the Marketplaces, which may reduce movement between plans and coverage types for people whose incomes fluctuate above and below Medicaid levels.4 New York’s BHP will be fully phased in as of January 2016, joining Minnesota as the second state with a BHP. When New York implemented its BHP, it stopped providing some additional Medicaid-funded subsidies to parents with incomes between 138% and 150% FPL who can now receive coverage through the BHP.

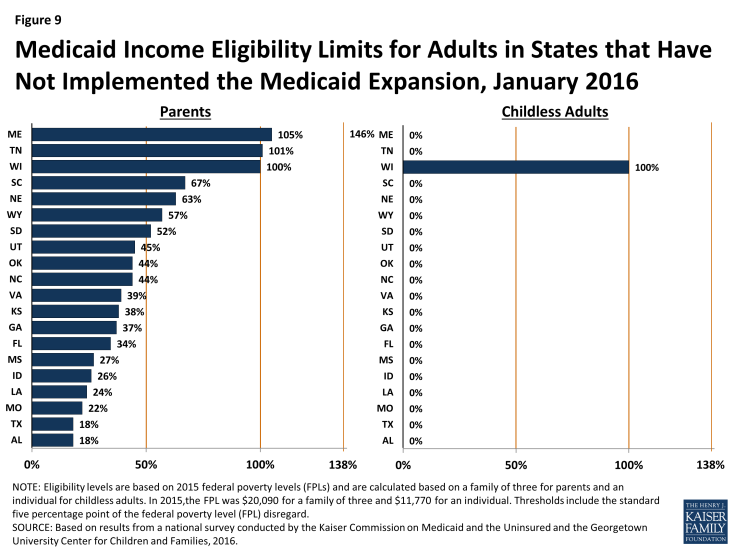

In the 20 states that have not expanded Medicaid, the median eligibility level for parents is 42% FPL; other adults remain ineligible regardless of income in all of these states except Wisconsin. Among the 2o non-expansion states, parent eligibility levels range from 18% FPL in Alabama and Texas to 105% FPL in Maine (Figure 9). Only 3 of these states—Maine, Tennessee, and Wisconsin—cover parents at or above 100% FPL, while 13 states limit parent eligibility to less than half the poverty level ($10,045 for a family of three as of 2015). Wisconsin is the only non-expansion state that provides full Medicaid coverage to other non-disabled adults, although its 100% FPL eligibility limit is lower than the ACA expansion level. While this study reports eligibility based on a percentage of the FPL, it also is important to note that 13 non-expansion states base eligibility for parents on dollar thresholds (which have been converted to an FPL equivalent in this report). Of those states, 12 do not routinely update the standards, resulting in eligibility levels that erode over time relative to the cost of living. Other analysis shows that three million poor adults fall into a coverage gap as a result of these low Medicaid eligibility levels in non-expansion states.5 These adults earn too much to qualify for Medicaid, but not enough to qualify for subsidies for Marketplace coverage, which are available only to those with incomes at or above 100% of FPL.

Figure 9: Medicaid Income Eligibility Limits for Adults in States that Have Not Implemented the Medicaid Expansion, January 2016

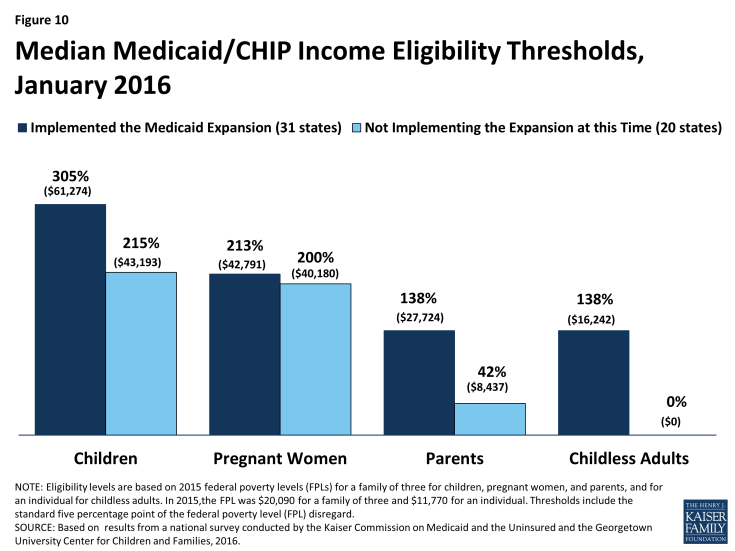

Eligibility levels for parents and other adults remain lower than those for children and pregnant women. Among expansion and non-expansion states, median eligibility levels for parents and other adults remain lower than those for pregnant women and children (Figure 10). In expansion states, median Medicaid and CHIP eligibility levels are 305% FPL for children and 213% FPL for pregnant women compared to 138% FPL for parents and other adults. However, these differences are more pronounced in states that have not implemented the Medicaid expansion. In the non-expansion states, the median Medicaid and CHIP eligibility level is 215% for children and 200% for pregnant women compared to 42% FPL for parents and 0% for other adults.