Beyond the Numbers: Access to Reproductive Health Care for Low-Income Women in Five Communities

St. Louis, MO

KFF: Usha Ranji, Michelle Long, and Alina Salganicoff

Health Management Associates: Sharon Silow-Carroll and Carrie Rosenzweig

Introduction

Over the past couple of decades, Missouri has increasingly become a battleground for reproductive rights and health services. The state has passed a number of regulations that restrict access to reproductive care, and in May 2019, along with several other states, the Republican-controlled Missouri state legislature passed a law banning abortions after 8 weeks. As of this publication, it is temporarily blocked by a federal judge as a legal challenge plays out in court. State regulatory policies and enforcement actions put Missouri at risk of becoming the first state with no operating abortion clinic since Roe v. Wade was decided in 1973. In addition to restrictions on abortion access, Missouri has not expanded Medicaid eligibility under the ACA.

Over the past couple of decades, Missouri has increasingly become a battleground for reproductive rights and health services. The state has passed a number of regulations that restrict access to reproductive care, and in May 2019, along with several other states, the Republican-controlled Missouri state legislature passed a law banning abortions after 8 weeks. As of this publication, it is temporarily blocked by a federal judge as a legal challenge plays out in court. State regulatory policies and enforcement actions put Missouri at risk of becoming the first state with no operating abortion clinic since Roe v. Wade was decided in 1973. In addition to restrictions on abortion access, Missouri has not expanded Medicaid eligibility under the ACA.

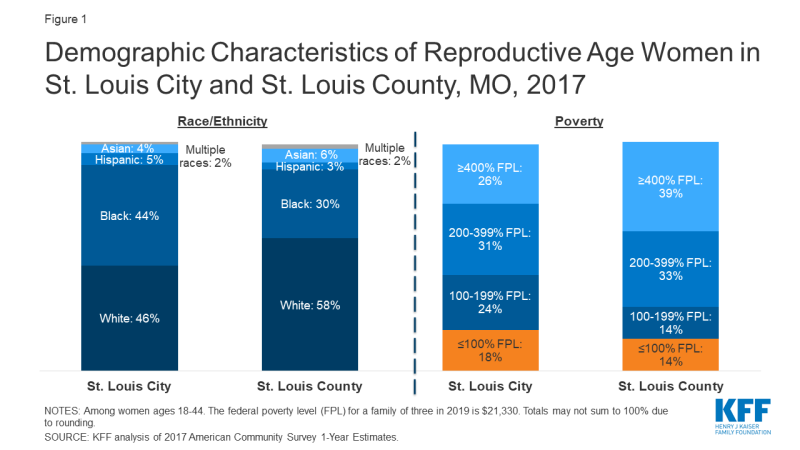

In contrast to the rest of the state, St. Louis stands out as a liberal area, electing Democrats as mayor of the City of St. Louis and to the state senate and House of Representatives.1 The St. Louis metropolitan area (Figure 1) is highly segregated and deep health disparities exist between black and white residents. The region is federally-designated as medically underserved and as a health professional shortage area. One recent study found that there was an 18-year difference in life expectancy between the wealthier, predominantly white, suburbs of Clayton and North St. Louis City, a majority Black area less than 10 miles away. St. Louis also has a large Catholic population and concentration of Catholic-affiliated hospitals and schools, which shape how local health systems offer sexual and reproductive health services and education.

This case study examines access to reproductive health services among low-income women in St. Louis City and County, Missouri. It is based on semi-structured interviews conducted by staff of KFF and Health Management Associates (HMA) with a range of local safety net clinicians and clinic directors, social service and community-based organizations, researchers, and health care advocates, as well as a focus group with low-income women during March and April 2019. Interviewees were asked about a wide range of topics that shape access to and use of reproductive health care services in their community, including availability of family planning and maternity services, provider supply and distribution, scope of sex education, abortion restrictions, and the impact of state and federal health financing and coverage policies locally. An Executive Summary and detailed project methodology are available at https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/report/beyond-the-numbers-access-to-reproductive-health-care-for-low-income-women-in-five-communities.

| Key Findings from Case Study Interviews and a Focus Group of Low-Income Women |

|

Figure 1: Demographic Characteristics of Reproductive Age Women in St. Louis City and St. Louis County, MO, 2017

Medicaid Coverage and Continuity

Missouri’s decision not to expand Medicaid, its policies restricting Medicaid reimbursement for providers that offer both contraception and abortion services, as well as the establishment of a state-funded family planning program that excludes providers who offer abortion services and their affiliates, have extensive implications for women’s access to sexual and reproductive health and maternity care. A temporary health care program for low-income adults in St. Louis helps fill some of the gaps in coverage and access to care.

| Table 1: Missouri Medicaid Eligibility Policies and Income Limits | |

| Medicaid Expansion | No |

| Medicaid Family Planning Program | No—Instead, Missouri operates an entirely state-funded program that provides family planning services to uninsured women ages 18-55 with incomes up to 206% FPL. Women losing Medicaid postpartum are also eligible |

| Medicaid Income Eligibility for Childless Adults, 2019 | 0% FPL |

| Medicaid Income Eligibility for Pregnant Women, 2019 | 305% FPL |

| Medicaid Income Eligibility for Parents, 2019 | 21% FPL |

| NOTE: The federal poverty level for a family of three in 2019 is $21,330. SOURCE: KFF State Health Facts, Medicaid and CHIP Indicators. |

|

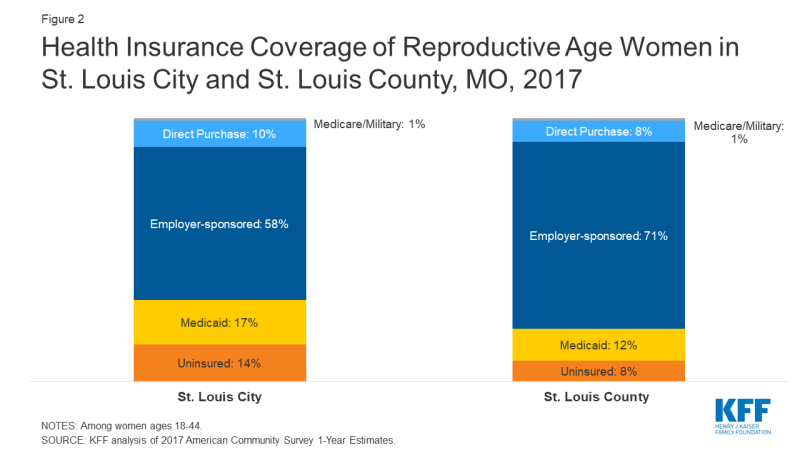

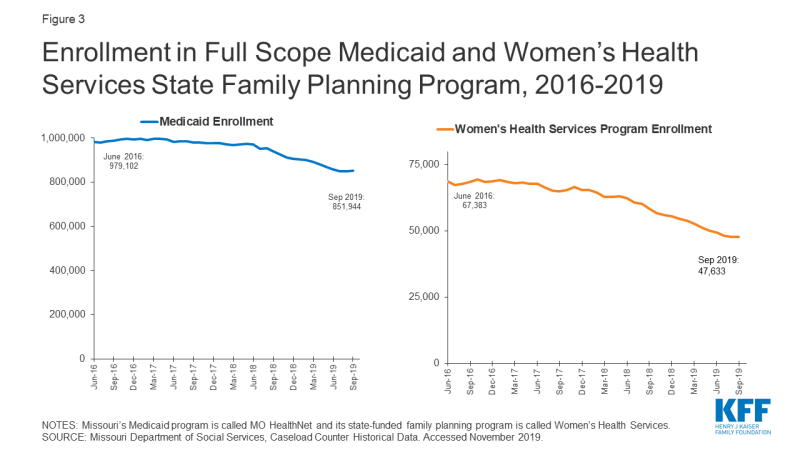

Missouri chose not to adopt the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion. Medicaid enrollment has declined dramatically over the past year, causing coverage gaps and discontinuity of care for women and children. Missouri’s Medicaid program (Table 1), MO HealthNet, covers parents with incomes under 21% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL), and pregnant women up to 305% FPL under the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) “unborn child” option (Show-Me Healthy Babies).2 Adults who are not parents are not eligible unless they are low-income and seniors or have a disability. Missouri’s Women’s Health Services program provides family planning services for women ages 18-55 who are ineligible for full Medicaid, with incomes up to 206% FPL, as long as they seek care at a family planning provider that does not also offer abortion services. Coverage gaps for women who do not qualify for Medicaid or who lose coverage due to small changes in income disrupt continuity of care and create barriers to family planning and other health care services (Figure 2). MO HealthNet enrollment declined roughly 9.5% from May 2018 to May 2019 (Figure 3), the steepest drop in Medicaid and CHIP coverage across all states. Missouri’s state government argues this decline is due to improvement in the economy, but a study by the Center for Children and Families at the Georgetown University Health Policy Institute suggests it resulted at least in part from flawed redetermination processes.

“In a state with high rates of maternal mortality and unintended pregnancy, [lack of Medicaid expansion] undermines women’s ability to have LARC [long-acting reversible contraception] if she wants it.”

–Ob-Gyn at a St. Louis hospital

In St. Louis City and County, uninsured adults living at or below 100% FPL, who do not qualify for Medicaid, can apply for the Gateway to Health program, a federal demonstration program that provides temporary coverage. Benefits include primary care, generic prescriptions, substance use treatment, and specialty care referrals to contracted health centers. There are no premiums and copays are no more than $3.00.

Figure 2: Health Insurance Coverage of Reproductive Age Women in St. Louis City and St. Louis County, MO, 2017

Lack of Medicaid expansion creates barriers to postpartum care. Missouri’s Medicaid income eligibility threshold for parents (21% FPL) is considerably lower than for pregnant women (305% FPL). Pregnancy-related coverage ends 60 days after delivery, so many poor women whose incomes exceed the 21% FPL threshold for parents (roughly $4,500 a year for a family of three) lose coverage two months after delivery. Furthermore, women with incomes below the federal poverty level are not eligible for subsidies to purchase private coverage through the ACA’s health insurance marketplace, meaning that many poor women do not have a pathway to coverage and become uninsured. One provider lamented that they are only able to see women once they are pregnant, but then must “drop them when they lose coverage.” There is no automatic enrollment into the state-funded family planning program for women who lose full Medicaid coverage, leaving many low-income women without coverage for needed contraceptive services after they have a baby. Providers suggested that the Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) in the area are positioned to provide ongoing care to women who lose their Medicaid coverage, but reported some FQHCs are facing steep financial challenges. In July 2019, the state announced plans to submit a Section 1115 Demonstration waiver to CMS that, if approved, would allow low-income women who have recently given birth and are diagnosed with a substance use disorder (SUD) to maintain coverage for SUD and related mental health treatment, including transportation to appointments, for up to 12 months following the end of their pregnancy benefits.

“You can’t optimize someone’s health care in nine months.”

–Dr. Melissa Tepe, VP/CMO, Affinia Healthcare

State policies bar Medicaid reimbursement for services obtained from providers who offer or are affiliated with abortion services. This reduces access to contraception for low-income women. To exclude abortion providers from participating in its Medicaid family planning program, in 2016, Missouri replaced its federal family planning waiver program with a state-funded family planning program called the Women’s Health Services Program. This program denies reimbursement to any organization that performs or counsels on abortion regardless of the other services that are provided. Additionally, in 2018, Missouri enacted legislation that denies Medicaid reimbursement to abortion facilities or their affiliates regardless of the other services that are provided.

Planned Parenthood of the St. Louis Region (PPSLR) had not received reimbursement for any of the Medicaid beneficiaries they served since July 2018, which makes up a significant portion of their budget. However, a state court judge ruled in June 2019 that Missouri unlawfully restricted Medicaid payments to abortion providers for non-abortion services and ordered the state to restore reimbursements to PPSLR.3 Medicaid reimbursement restrictions also create confusion among health care providers, which one interviewee suggested causes fewer providers to participate in the state family planning program even if they are qualified. Between June 2018 and May 2019, enrollment in the Women’s Health Services Program dropped by almost 12,000 members, or almost 19% (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Enrollment in Full Scope Medicaid and Women’s Health Services State Family Planning Program, 2016-2019

These policies also threaten the financial stability of clinics that provide free or affordable contraception to low-income women, even if they do not provide abortion. For example, the Contraceptive Choice Center (C3), part of the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, was excluded from the state family planning program due to its affiliation with a hospital that provides abortions in cases of severe fetal anomalies or when a woman’s life is in danger.

The state’s Title X clinics may be strained after the Trump Administration’s new program rules are fully implemented. In addition to Medicaid, funds from the federal Title X family planning program support clinics that provide services to low-income women. In March 2019, the Trump Administration issued new rules barring Title X funding from organizations that provide or refer for abortion. At that time, a C3 clinic interviewee stated that should the new rules be implemented, the clinic may have to shut down entirely. Since the time of the interview, the rule has gone into effect and Planned Parenthood has withdrawn from Title X nationwide; the effect on C3 remains to be seen.4

Focus group participants cited cost as a major barrier to health insurance coverage and care. Most focus group participants reported that they are getting their basic health needs met, but a few uninsured women are going without some types of health care such as preventive care, dental care, mental health services, or their preferred method of contraception. For uninsured women, the cost of birth control ranged from $25 to $48 per month. One focus group participant said she wanted to change methods but could not afford the $170 appointment to have her intrauterine device (IUD) removed, and another could not afford a tubal ligation she desired.

| Initiative: Contraceptive CHOICE Center (C3) |

| The Contraceptive Choice Center (C3) grew out of a cohort study that provided no-cost reversible contraception to almost 10,000 women in the St. Louis area over the course of 2-3 years. The goal was to increase uptake of long acting reversible contraception (LARC) and decrease unintended pregnancy using a patient-centered approach and comprehensive counseling. Program evaluation documented a reduction in teen pregnancy, births, and abortions in the cohort from 2006 to 2010. C3 is now a Title X grantee providing comprehensive gynecological and family planning services with sliding scale fees for low-income women. They receive 2,500-3,000 visits a year, with one third of patients uninsured, and a quarter covered by Medicaid. Most (60%) of their patients are below 100% FPL and qualify for care at no cost. |

Provider Distribution and Religious Health Systems

Provider distribution remains a problem in the St. Louis area, especially in low-income areas, and the prevalence of faith-based hospitals may cause delays in care. While overall there are sufficient numbers of providers offering affordable contraceptive and pregnancy-related care, maldistribution of providers translates into access problems for many women.

While interviewees reported there are enough providers of publicly-funded contraception within the city limits, they do not feel that they are distributed equitably throughout the county. Interviewees identified provider shortages in North City and North County, areas that are majority low-income and African American, and in other pockets of poverty throughout the county. There are four Title X providers in St. Louis, but there is no public hospital in the area; this need is primarily filled by private or faith-based hospitals. Some reported that there is also a lack of providers trained in long acting reversible contraception (LARC) insertion in publicly funded clinics.

Several health care leaders stated that there is insufficient capacity to meet the demand for sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing and treatment in the face of high and increasing rates of syphilis, chlamydia, and gonorrhea. Following nationwide trends, rates of STIs are increasing in St. Louis, with the highest prevalence among people living with HIV, African Americans, and youth ages 16 to 24. Access to STI testing and treatment is limited by a lack of affordable providers and decreasing federal and state funding. After the city health department closed its STI clinics in the early 2000’s, the county clinic in North County became the only public provider in the area, with lines out the door on most of their STI clinic days. Focus group participants reported that men in particular are not receiving adequate STI testing and treatment services because they are not as connected with the health system and usually ineligible for Medicaid. Therefore, most are not getting preventive care or education about STI prevention, which reduces the likelihood they will seek treatment if they have an infection.

Interviewees and focus group participants felt that there was generally an adequate supply of providers for pregnancy and postpartum services in the St. Louis region and that access was better than in the rest of state. Overall, women participating in the focus group participants reported having positive experiences at the hospitals where they received maternity care and felt their physicians understood their cultural beliefs. They also reported their physicians discussed contraceptive options with them during the 6-week postpartum visit. The County Health Department is a service site for the Nurse Family Partnership program, one of the local programs that makes home visits to low-income first-time mothers and has been effective in improving the utilization of contraceptives during the postpartum period.

Religious health systems do not offer most methods of contraception, but clinicians affiliated with those systems often refer to other providers for a broader range of options. Most focus group participants had received care from one of the area’s many Catholic hospitals, and they did not report any significant impact on their reproductive health care. Although they knew that these hospitals would not perform tubal ligations, they said that their physicians shared information about contraceptive methods and would provide referrals to other hospitals or clinics where they could obtain these services. None of the women knew that there was a non-religiously affiliated hospital in the area. Community stakeholders similarly reported that individual providers affiliated with religious health systems may refer to other providers for contraceptive services not permitted by their institution.

Certain hospitals won’t even allow [tubal ligation] …So you can’t have it there, so if you want your doctor to do it you have to find a way for your doctor to do it at another facility that will allow it to happen.”

–Focus group participant

| Initiative: Enhanced centering pregnancy pilot |

| Enhanced Centering Pregnancy is a group prenatal care pilot program. The program seeks to increase the availability of trauma-informed care, address racism and bias in the health care system, and integrate behavioral and medical services to improve outcomes for pregnant women in the St. Louis region. St. Louis Integrated Health Network is leading this two-year initiative in partnership with Affinia Healthcare, two local hospitals (Barnes Jewish and SSM Health St. Mary’s), and community health centers. |

Contraceptive Provision, Access, and Use

Overall, interviewees felt that women living in the St. Louis region can obtain their preferred method of contraception, but cited barriers related to transportation and poverty. They also noted that a lack of comprehensive sex education can impede knowledge of the full range of methods. Several promising efforts are underway to address these barriers and improve access for low-income women.

Family planning providers offer a wide range of contraceptive choices including IUDs and implants, but certain Medicaid policies challenge their ability to offer same-day or timely access to LARCs. Most providers reported they offer comprehensive family planning services. Missouri’s state Medicaid program covers LARC at the time of delivery with a separate provider reimbursement to promote immediate postpartum LARC insertions. Interviewees reported, however, that some hospitals are not aware of this policy or need additional training in LARC insertion to make this option fully available after delivery. Furthermore, several providers noted that Medicaid policies governing payment for LARC cause delays that prevent same-day access. These policies include preauthorization and utilization requirements that limit a patient to one LARC device per FDA-approval period for the device (e.g. up to five years for a Mirena IUD), and policies tying LARC devices to a specific patient. As a result, most patients must return for a second appointment to get their device inserted, and many interviewees reported instances of patients missing appointments or getting pregnant before they are able to return. One focus group participant explained she had to wait three months for her IUD to be delivered because of Medicaid’s pre-authorization requirement. Many clinics cannot afford the high upfront costs to stock LARCs onsite, which would facilitate same-day access for women seeking those methods. In 2018, legislation was passed that allows a provider to transfer a new, unused LARC to a different MO HealthNet patient instead of discarding it. However, one provider noted that there were not yet any guidelines from the state to define or help facilitate that process.

“Sometimes we give someone a depo shot to bridge someone who wants a LARC – would be more cost effective to just give them the LARC upfront. There are better ways to give people what they want when they want it, but there are too many barriers.”

–Dr. Katie Plax, Medical Director, Supporting Positive Opportunities with Teens (the SPOT)

While most focus group participants reported that they can get contraception, many described barriers to getting the methods they want, when they want them. Several focus group participants said they are happy with the treatment they receive from their providers when seeking contraception and are familiar with a wide range of contraceptive methods. However, it can take multiple visits and long wait times between appointments is common. One woman who now goes to a public health clinic after losing her private insurance said she has been waiting months for an appointment because of staff shortages due to furloughs. Several focus group participants had experienced negative side effects from hormonal methods that resulted in their changing or discontinuing contraception. Focus group participants were knowledgeable about emergency contraception, and four had used it in the past. They said it is available at drug stores, but that they must ask for the pharmacist to take it out of a locked case, creating additional barriers to access.

Some low-income women experience financial, logistical, and language barriers to accessing family planning services. Poverty and other socioeconomic factors also affect sexual health outcomes. Interviewees noted a lack of reliable public transportation, scheduling conflicts, long waiting times for appointments, and lack of interpretation services as barriers to care. Providers stated that the safety net was over capacity, with six to eight-week wait times for a women’s health appointment for new FQHC patients. One focus group participant liked that her usual place of care had extended hours during the evening, so she could go after work. Factors such as unstable housing, lack of transportation, poverty, and a lack of education were raised as challenges for low-income women, and these are fundamentally intertwined with sexual and reproductive health services.

“People don’t like to think that housing and sexual health are related, but I have patients who are trading sex for a roof over their head–both men and women.”

–Dr. Katie Plax, Medical Director, the SPOT

Clinicians face time constraints during family planning visits, and some are influenced by their own beliefs or outdated standards of care. Several clinic staff mentioned that clinicians do not have enough time to provide in-depth contraceptive counseling given the clinic flow and the level of demand. Likewise, focus group participants reported that the physicians are too busy to spend much time with them. Lack of provider training and misinformation also impede family planning access, especially around LARC provision. Some providers still adhere to outdated protocols restricting IUD use for women who have not had children. Others may not be providing comprehensive counseling on the full range of methods due to their own cultural or religious beliefs. One interviewee reported that there may be variation within organizations, with pushback from some individual providers and nursing staff regarding the use of LARCs or emergency contraception.

“It takes time to fully counsel someone on birth control, birth spacing, the most effective method, side effects, and patient preference. I would prefer to spend more time counseling on different methods than on talking about costs and completing paperwork.”

–Dr. Melissa Tepe, VP/CMO, Affinia Healthcare

| Initiative: The Right Time |

| Launched in April 2019, the Right Time is a six-year, state-wide initiative, led by the Missouri Family Health Council and funded by the Missouri Foundation for Health. It focuses on reducing cost barriers to family planning, increasing the quality and availability of contraceptive services, and reducing disparities among low-income women, women of color, and those living in rural areas. The program’s ultimate goal is to reduce Missouri’s unintended pregnancy rate by 10% by 2024. Three of the first six health centers in the state selected to participate are in St. Louis City. |

Sex Education Policy and Provision

Sex education in schools is not mandated and varies by district. “Abstinence-plus” is the most common approach. In 2007, Missouri passed a law that prohibited school districts from allowing a person or an organization to offer sex education or related materials to its students if they provide or refer to abortion services. One interviewee said that this policy leads to a lot of confusion and individual interpretation at both the administrative and teacher level. It also opens the door for faith-based organizations, such as Crisis Pregnancy Centers (CPCs), which often do not offer a medically-accurate, comprehensive curriculum, to step in. While parent pushback resulted in some schools no longer using CPCs to provide sex education, other schools reportedly continue to use “abstinence only” education or “abstinence-plus” curricula, which stress abstinence but also include information on contraception and condoms. PPSLR offers comprehensive sex education at no cost to hundreds of partners a year, but interviewees say the rule barring abortion providers from offering sex education in schools has a chilling effect despite their legal separation from Reproductive Health Services (RHS), the Planned Parenthood clinic that conducts abortions. Interviewees and focus group participants agree that as a result, youth are not adequately informed of sexual health risks or ways to prevent unintended pregnancy and STIs. Focus group participants believed that most young women rely on their friends for information, and that the gaps in sex education results in teen pregnancies.

“Women are bombarded with a wealth of misinformation, so it’s hard to know what is true and whom to trust.”

–Michelle Trupiano, Executive Director, Missouri Family Health Council, Inc.“Lack of awareness leads to a lack of access.”

–Thomas McAuliffe, Director of Health Policy, Missouri Foundation for Health

| Initiative: Supporting Positive Opportunities with Teens (SPOT) |

| The SPOT is a freestanding site that provides teen-friendly health care, mental health care, and express STI testing at no cost, as well as case management to address social determinants of health. They also have a school-based health center (SBHC) in a North County public high school, which is one of the first comprehensive SBHC programs in the area. The SPOT served 3,253 St. Louis teens in 2018 (80% Black, 17% LGBT, and 2-3% transgender and gender nonconforming youth). |

Access to Abortion Counseling and Services

Abortion is highly regulated in Missouri, and women face significant barriers to accessing abortion counseling and services.

The only clinic that provides abortions in the state of Missouri is in St. Louis. Women are increasingly crossing state lines to seek services at clinics in Illinois where there are fewer state restrictions. As of November 2019, RHS of PPSLR, located in the city of St. Louis, is the only clinic providing abortions in Missouri, down from three clinics in 2018.5,6 Notably, there is no access to medication abortion in Missouri. RHS provides surgical abortion services, but stopped providing medication abortion because Missouri regulations require providers to conduct a pelvic exam prior to medication prescription; RHS providers consider this medically unnecessary and unethical. Instead, they refer women seeking medication abortion to a Planned Parenthood clinic in Illinois. Consequently, more women are reportedly going across the river to the Planned Parenthood and Hope Clinic for Women, an independent provider, in Illinois, where there are fewer state restrictions including no waiting period. Planned Parenthood is expanding services in their southern Illinois facility to help meet demand for the surrounding region. While access is difficult in St. Louis City and the surrounding county, interviewees agree that access is significantly harder in the rest of the state where there are no nearby abortion providers, and women may have to travel up to five hours to St. Louis for care.

“I’ve seen clinics close. I used to have a Planned Parenthood down the way from me and it’s gone. I don’t know, I can’t even tell you how long it’s been gone now. I couldn’t tell you where the closest one is, if I needed to go to one.”

–Focus group participant“Either we will end up in Handmaid’s tale or people will actually get out in the street and fight against these processes.”

“We are hopeful for St. Louis only because it has bridges into Illinois, which is moving in the other direction.”

–Dr. David Eisenberg, former Medical Director, Planned Parenthood of the St. Louis Region

Focus group participants reported that cost is the largest barrier to abortion care but that many other abortion-specific restrictions also make abortion access challenging. Focus group participants said the cost for the abortion pill is between $500 and $600, and surgical abortion costs around $700, making it out of reach for many women. They also cited other barriers such as transportation, a shortage of providers, and regulations such as the 72-hour waiting period, mandated informed consent counseling, parental consent for minors, and gestational age limits. Some focus group participants felt the state-mandated counseling was intended to make them second guess their own decisions. A few focus group participants were well informed about the state’s abortion laws, and most felt that it was getting harder to get an abortion in Missouri. Some women said they have gone to neighboring clinics in Illinois where there are fewer restrictions.

The volume of state and federal restrictions on abortion have a profound impact on providers and the low-income women they serve. Providers reported that the 72-hour waiting period coupled with the rule that requires the same physician to conduct the informed consent and the procedure three days later are especially burdensome. As a result, RHS had to reconfigure their scheduling to accommodate these policies, losing four providers who could no longer fit it into their schedule. The new Title X rule, which blocks funding for family planning providers who refer women for abortions, is confusing to providers regardless of whether they participate in the Title X program; they reported that when the rules constantly change, they are wary of even providing a referral for abortion. One interviewee reported that FQHC providers have been told never to talk about abortion and are worried about doing anything that would put their federal funding in jeopardy.7 One provider noted that the media mainly discuss the rule’s impact on Planned Parenthood affiliates but believes there would be a much more dramatic effect on other providers, either because they would not want to comply with the rules and choose not to participate in the Title X program, or they were not able to participate. This would mean that they would lose an important source of funding to provide family planning services to poor and uninsured women.

“When there are rules and the rules constantly change, a provider will not feel comfortable giving information about access to abortion or even to do referrals [to make sure you are not breaking the law with penalties that now can include criminal charges].”

–Dr. Katie Plax, Medical Director, the SPOT

Abortion providers and women who utilize their services feel stigmatized and sometimes fearful by the political and social barriers they face in providing and seeking abortion care. Stigma, intimidation, and fear about confidentiality serve as major barriers to women seeking abortion services. There are protestors outside PPSLR and RHS daily, and focus group participants reported that these protestors make them feel afraid and ashamed of their decisions. Crisis pregnancy centers (CPCs), which typically offer limited medical services like pregnancy tests and ultrasounds, and discourage women from seeking abortion, have a large presence in the area. Abortion providers also face a series of obstacles, including myriad state restrictions (see Appendix) and significant cultural and political stigma. One clinician noted she chose not to provide abortion services because the associated stigma would make it difficult for her to be effective in other areas of health care and state health policy due to the political environment. Another interviewee said their organization is seeking long-term political solutions such as the “Clean Missouri” bill that addresses gerrymandering in the state to help elect officials who are supportive of reproductive health and abortion services.

“It’s only one location and, I mean on some days it’s probably even scary to walk in a location that’s full of people with signs out.”

–Focus group participant“Speaking for myself, it’s hard to talk about abortion because of the stigma and politics surrounding it. It is framed in a way that it is difficult to talk about without feeling guilty or uncomfortable…We should frame it around health, women’s empowerment, caring and supporting women, interpregnancy care and planning, and supporting families after a baby is born.”

–Dr. Melissa Tepe, VP/CMO, Affinia Healthcare

Conclusion

While St. Louis has an extensive network of family planning and maternity providers, women who live in the poorest areas of the city and county are especially disadvantaged due to the dearth of providers in their communities and the lack of reliable public transportation to clinics in other areas. Several organizations in the region have undertaken efforts to expand access to contraception, especially to highly-effective, long-acting methods such as IUDs and implants. However, there is a large contrast between the efforts to improve access in St. Louis and state-level policy decisions that have targeted family planning providers that also offer or are affiliated with abortion providers. Providers said that these policies limit their ability to participate in programs like the state family planning program and Title X. The state’s decision not to expand Medicaid and recent efforts to further restrict access to abortion have not only significantly reduced the availability of abortion services, but also have had an impact on contraceptive access, STI care, and other basic health services. More women are reportedly choosing to travel to Illinois for abortion services, where they have far fewer restrictions on abortion.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all of the interviewees for their insights, time, and helpful comments. All interviewees who agreed to be identified are listed below. The authors also thank the focus group participants, who were guaranteed anonymity and thus are not identified by name.

Meg Boyko, Executive Director, Teen Pregnancy & Prevention Partnership

David Eisenberg, Board-Certified Ob-Gyn and Former Medical Director, Planned Parenthood of St. Louis Region (PPSLR)

Linda Locke, Board President, (PPSLR)

Tessa Madden, MD, MPH, Contraceptive Choice Center (C3), Washington University School of Medicine

Katharine Mathews, MD, MPH, MBA, Associate Professor and Research Division Director, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Women’s Health, Saint Louis University School of Medicine

Thomas McAuliffe, Director of Health Policy, Missouri Foundation for Health

Tim McBride, PhD, Professor and Co-Director of Center for Health Economics and Policy, Institute for Public Health, Washington University in St. Louis

Colleen McNicholas, DO, Chief Medical Officer, PPSLR

Katie Plax, MD, Medical Director, Supporting Positive Opportunities with Teens (The SPOT), Washington University in St. Louis

Angie Postal, Vice President, Education, Policy, and Community Engagement, PPSLR

Becky Schrama, MA, BSN, RN, Public Health Nursing Manager, St. Louis County Department of Public Health

Melissa Tepe, MD, MPH, FACOG, VP/CMO at Affinia Healthcare, St. Louis, MO

Michelle Trupiano, MSW, Executive Director, Missouri Family Health Council, Inc.

Appendix

| Missouri State-Level Policies Related to Abortion |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| SOURCE: KFF, State Health Facts, Abortion Statistics and Policies. Guttmacher Institute, State Facts About Abortion: Missouri. |