Snapshots of Recent State Initiatives in Medicaid Prescription Drug Cost Control

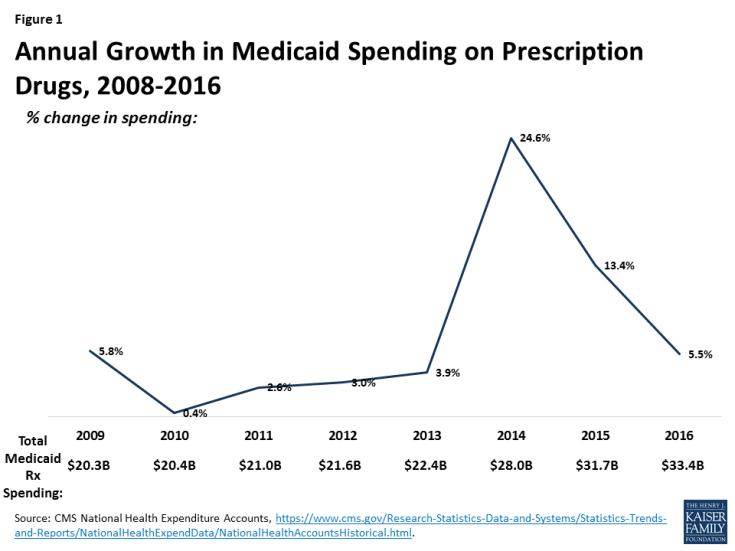

After several years of spending growth below five percent, Medicaid spending on outpatient drugs increased 25 percent from $22.4 billion in 2013 to $28 billion in 2014 and another 13 percent in 2015 to $31.7 billion (Figure 1).1 This spike in 2014-2015 is in large part attributed to Sovaldi, Harvoni, and Viekira Pak2, the breakthrough hepatitis C Direct Acting Antivirals that came to market in 2013 and 2014. The high cost of specialty drugs and certain classes of drugs, the rapid rise in generic drug prices from some manufacturers in 2015, and the price hikes of Mylan’s EpiPen in 2016, fueled concern among policymakers and the public about rising drug costs.3 However, reflecting system-wide trends, Medicaid drug spending growth slowed in 2016, though recent rates of prescription drug spending growth in Medicaid are still higher than other payers. Although drug spending constitutes only 6% of Medicaid total spending,4 the high cost of specialty drugs continues to be a concern among Medicaid policy directors looking to control future spending.5

Due to the structure of Medicaid’s rebate program, states are generally obligated to provide a drug to their beneficiaries when it comes on the market and currently cannot exclude high cost drugs from their programs. In the early 2000s, prescription management programs, which included preferred drug lists, supplemental rebates, and script limits, were implemented and expanded by states in an effort to control costs.6 However, these programs have reached maturity, and states, facing the prospect of more new and costly drugs coming to market, are now looking to develop new ways to achieve savings in the prescription drug program. This issue brief provides a snapshot of current state initiatives aimed at addressing the cost of prescription drugs in Medicaid.

Background: How does Medicaid pay for prescription drugs?

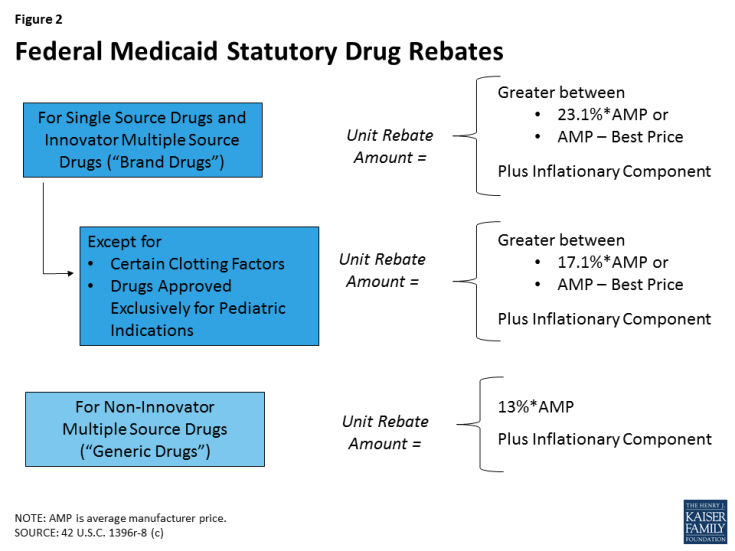

States’ methods of paying for outpatient prescription drugs in Medicaid vary but are bound by federal requirements regarding the federal rebate program and allowable schedules for reimbursement. Under federal law, in order for a drug to qualify for federal statutory Medicaid matching funds, manufacturers must sign an agreement with the Secretary of Health and Human Services stating that they will rebate a specified portion of the Medicaid payment for the drug to the states, which in turn share the rebates with the federal government. In return, Medicaid must cover almost all FDA-approved drugs that those manufacturers produce. The formula for the amount of the rebate is set in statute7 and varies by type of drug (brand or generic) (Figure 2). Rebates apply regardless of whether a state pays for prescription drugs on a fee-for-service basis or includes them in capitation payments to managed care plans. As discussed in detail below, most states also negotiate supplemental rebates with manufacturers.8

For Medicaid drugs provided on a fee-for-service basis, state payment includes both a dispensing fee (amount paid to the pharmacy for the work of filling the prescription) and payment for the ingredient cost (amount paid to the pharmacy for the cost of the drug). States have flexibility to set professional dispensing fees. In setting the ingredient cost, states now have to base payment on the Actual Acquisition Cost (AAC) for a drug.9 The federal Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) allows states to use certain schedules as AAC and encourages states to use the National Average Drug Acquisition Cost (NADAC).10 The NADAC is intended to be a national average of the prices at which pharmacies purchase a prescription drug, including some rebates. These federal rules regarding allowable schedules do not apply to Medicaid drugs provided through managed care.11

Many states also use pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) in their Medicaid prescription drug programs. PBMs perform financial and clinical services for the program, administering rebates, monitoring utilization, and overseeing preferred drug lists.12 PBMs may be used regardless of whether the state administers the benefit through managed care or on a fee-for-service basis.

What policy levers have states traditionally used to control Medicaid drug spending?

Within federal rules regarding the federal rebate agreement and medical necessity requirements, states have flexibility in administering their Medicaid prescription drug programs. States have used a variety of strategies to contain pharmacy costs and have done so for many years. Common strategies include implementing prescription limits, negotiating supplemental rebates, requiring prior authorizations, and using state Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC)13 programs. States also have joined multi-state purchasing pools when negotiating supplemental Medicaid rebates to increase their negotiating power, and states have switched ingredient cost methodologies.14 Most state Medicaid programs also maintain a preferred drug list (PDL) of outpatient prescription drugs,15 which is a list of drugs states encourage providers to prescribe over other drugs. A state may require a prior authorization for a drug not on a preferred drug list. PDLs create incentives for a provider to prescribe a drug on the PDL if possible. Often, drugs on PDLs are cheaper or include drugs for which a manufacturer has provided supplemental rebates. While states may require prior authorization, restrict access to drugs only being used for medically accepted indications, or not cover certain specific drugs that are listed in the statute, outside of these allowances, they are required to provide nearly all prescribed drugs made by manufacturers that have entered into a rebate agreement. 16 This requirement holds regardless of whether the beneficiary receives prescriptions in a managed care or fee-for-service setting.

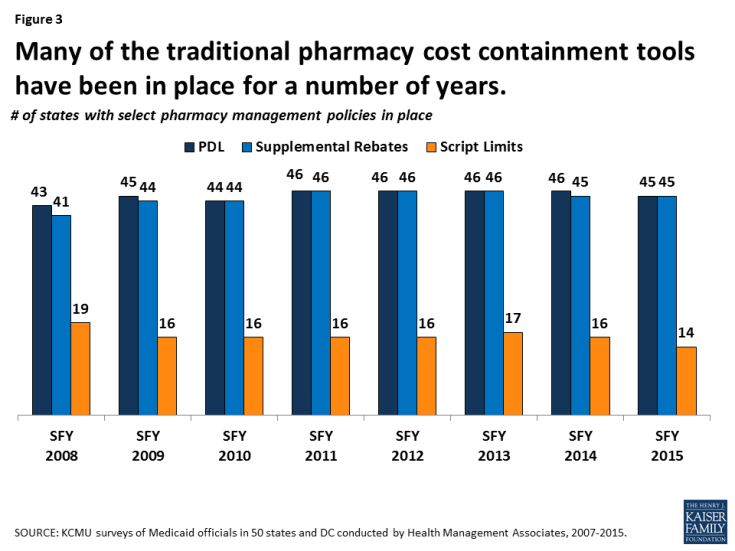

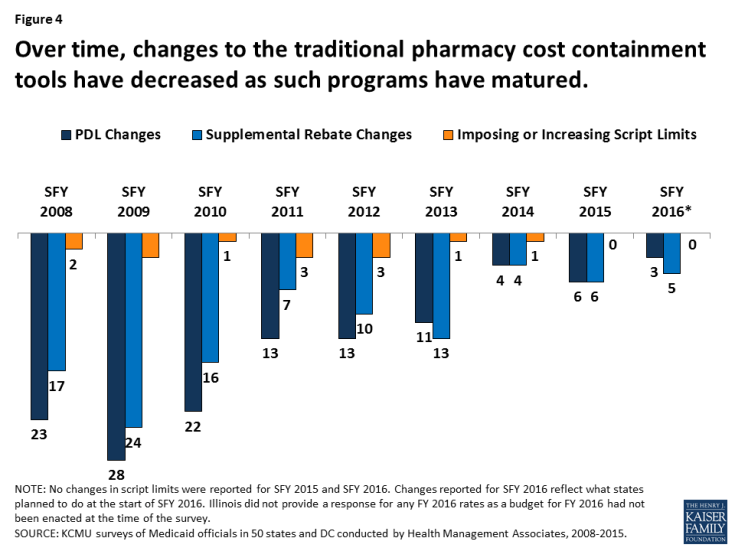

States have used these strategies in Medicaid for many years (Figure 3). However, such actions have slowed in recent years as economic conditions have improved and states reach the limits of utilization controls allowed under federal law (Figure 4).

Figure 3: Many of the traditional pharmacy cost containment tools have been in place for a number of years.

Figure 4: Over time, changes to the traditional pharmacy cost containment tools have decreased as such programs have matured.

High-Cost Specialty Drugs & Limits on Traditional Pharmacy Management Controls

FDA approval of Sovaldi in December 2013 created a fiscal challenge to states’ Medicaid drug programs. Sovaldi, a direct acting antiviral (DAA), was a major advance in the treatment of hepatitis C (HCV) in that it essentially cures the disease in most people while causing minimal side effects. Previous treatments had been much less successful and had debilitating side effects. However, the list price of Sovaldi was $84,000 for a typical course of treatment. Even with the federally-required Medicaid rebate, Sovaldi remained expensive to Medicaid, and limited competition in the drug class made it difficult for states to initially use PDLs to obtain supplemental rebates. Because a disproportionate number of people with HCV are enrolled in public programs, Medicaid financed a large share of DAA treatment.17

Many state Medicaid programs implemented utilization controls for Sovaldi: in 2014 and 2015, over half of the state Medicaid programs had implemented prior authorization restrictions for DAAs, and nearly all of those based the prior authorization on the degree of the patient’s liver damage.18 In addition to restrictions based on the extent of liver damage, some states also required that a patient meet with a specialist, as well as drug counseling, drug testing, and periods of abstinence from drugs and alcohol. However, these restrictions were inconsistent with treatment recommendations and with federal law about drug utilization control. Class actions were filed in federal courts in a number of states, and in May 2016, a federal court issued a preliminary injunction ordering Washington State to provide DAAs to all Medicaid beneficiaries with the virus.19 Following these legal actions, many states loosened restrictions on DAAs, and some now provide DAAs to all Medicaid beneficiaries. Despite increased competition,20 DAAs remain expensive, and states continue to grapple with the high cost of specialty drugs. In addition, although states have placed particular focus on DAAs, they remain vigilant about other high cost drugs as well, such as hemophilia, oncology, and diabetes classes of drugs.21 Most states have been looking for new ways to control drug spending.

What new Medicaid strategies are states trying to control drug spending?

Some new strategies that states are trying aim to expand the scope of efforts already underway in Medicaid or implement new Medicaid policies not previously allowed under federal law. In general, these efforts share a goal of obtaining greater supplemental rebates from manufacturers. Currently, states use placement on their PDL as a means to negotiate supplemental rebates. States often join in multi-state pools to have greater leverage to obtain supplemental rebates.22 New strategies include state spending caps for Medicaid prescription drugs and a proposal of a closed formulary in Medicaid.

Drug Growth Caps

One idea currently being tested is use of a spending growth cap for Medicaid prescription drugs. If spending is above the cap, the state undertakes close review of drug spending and targets certain drugs for additional utilization review.

New York is currently implementing such a process. The state has had a spending cap on its Medicaid program since 2011.23 However, drug expenditures have continually grown faster than other cost components under the cap.24 As a result, in April 2017, the governor signed into law25 the addition of a drug cap as a separate component of the spending cap. Under this drug cap, if total Medicaid drug spending in a year is projected to exceed the growth target, the state Commissioner of Health may identify specific drugs for referral to a Drug Utilization Review Board (DUR Board)26 and reach out to the manufacturer to see if they can agree on a satisfactory rebate for the specified drugs. If the Department of Health and the manufacturer cannot reach an agreement, the Commissioner may refer the drug to the DUR Board, which considers a variety of factors about the specified drugs, such as the cost of the drug including rebates, its impact on the drug spending growth target, and its value to Medicaid beneficiaries. After considering these factors, the DUR Board may seek additional supplemental rebates with the manufacturers. If the department is unable to obtain the desired additional supplementary rebates, the manufacturer must provide information to the department on the drug in question including the cost of development and manufacturing, R&D costs, advertising costs, utilization, prices charged outside the U.S., average rebates, and average profit margin. This information is not provided to the public. Ultimately, if Medicaid drug spending is greater than the annual growth rate, the Commissioner can further limit access to the drug through existing utilization controls allowed under current law.

Closed Formularies

As stated earlier, once a manufacturer signs a Medicaid rebate agreement with the Secretary of HHS, states must provide nearly all of that manufacturer’s drug products to its Medicaid beneficiaries, essentially creating an open formulary. States can use PDLs to provide incentives for prescribers, but the state must still make drugs not on the PDL available after the prescriber has received a response for prior authorization if the drug is prescribed for a medically accepted indication.27 This approach stands in contrast to a closed formulary, under which only specific drugs in each therapeutic class are covered. Some feel that allowing states to implement “widely-used commercial tools”28 such as closed formularies would allow states to negotiate greater rebates, because each manufacturer would want their drug to be included as one of the few drugs for the therapeutic class.

| The Administration’s Discussion of a New Demonstration Authority and Encouraging Generic Entry |

| The administration has also expressed interest in state Medicaid programs having the ability to utilize formularies, as is done in the private sector. The FY 2019 budget* calls for a new Medicaid demonstration authority to enable up to five state Medicaid programs to create their own formularies and negotiate directly with manufacturers instead of participating in the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program. Prices negotiated through this demonstration would be exempt from Best Price (see Appendix). These states would also maintain an appeals process for non-covered drugs. The Administration also calls for actions to increase the number of generic drug applicants.

*FY 2019 HHS Budget in Brief, “Putting America’s Health First, FY 2019 President’s Budget for HHS,” https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/fy-2019-budget-in-brief.pdf |

In September 2017, Massachusetts submitted an application to CMS that included a provision to amend its Section 1115 Medicaid demonstration waiver to create a closed formulary.29 The state specified that the closed formulary would include at least one drug per therapeutic class and that the state would have the ability to exclude drugs with limited evidence for clinical efficacy. However, the state Medicaid program would also include an exceptions process for drugs not included in the formulary. The application is pending as of the publication of this brief. In November 2017, the state of Arizona indicated to CMS that it is considering a similar proposal in its upcoming Section 1115 waiver amendment.

What broader efforts are states trying to control drug spending?

In addition to actions within Medicaid, states are undertaking efforts to control drug spending across payers. While not specific to Medicaid, these activities would also affect Medicaid drug spending.

Promoting Low Price Generic Drugs

Generic drugs have long been considered the affordable, reliable alternatives to expensive brand name drugs. However, in recent years, a variety of payers, including state Medicaid agencies, have faced price increases for many generic drugs.30 One possible reason for price increases is decreasing competition within the generic market, which concentrates market power and gives manufacturers leverage to set prices.31 Some point to the wait time for FDA generic approvals contributing to the fewer number of manufacturers for each product. However, in some cases, there are multiple manufacturers producing the same generic drug, and counter to expectations, the price for the generic drug increases regardless. Generic drug manufacturers also point to supply problems in active pharmaceutical ingredients; manufacturing challenges for certain drugs such as narcotics or sterile products; a decrease in the number of manufacturers due to mergers and acquisitions; a decrease in buyers due to mergers and acquisitions; and small populations using the generic drug.32

Since January 2017, the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program has incorporated an inflationary component in the calculation of rebates for generic drugs that aims to keep the net price increase to Medicaid flat in real dollars.33 However, due to the complex nature of pricing and reimbursement, this mechanism does not necessarily limit all cost increases for generic drugs in Medicaid, as Medicaid payments to pharmacies use a separate (though related) payment base. Additionally, even limiting Medicaid spending for generics to inflation is problematic, as the expectation is that the price of generic drugs will decline over time due to competition.

States have been taking action to address the cost of generics and shift utilization towards lower cost generics and biosimilars. These actions include new laws to prevent price gouging, lawsuits to recoup damages from alleged collusion in price increases, and efforts to promote biosimilar substitution for biologics.

Limits on Generic Price Increases

Some states have directly sought to limit price increases in generic drugs—for all payers in the state, including Medicaid—through legal action. In May 2017, Maryland passed the first U.S. price-gouging prohibition law.34 The law addresses increasing prices of generic or off-patent drugs with few manufacturers and only applies to scenarios where the drug is manufactured by three or fewer manufacturers. In the event that a manufacturer raises the “Wholesale Acquisition Cost” (WAC) of a generic or off-patent drug by more than 50% in a year, or the price paid by the Maryland state Medicaid program increases by more than 50% in a year, the Maryland Medicaid program may notify the Attorney General. From there, the Attorney General may request detailed information from manufacturers justifying the price increase. The Attorney General also may pursue legal action, and a circuit court may impose civil penalties of up to $10,000 for each violation. The circuit court also may require manufacturers to provide the drug to Maryland state programs at the price prior to the increase. Although the law went into effect in October 1, 2017, it faces court challenges and lacks the support of the governor.35

|

FDA Drug Competition Action Plan to Increase the Number of Generic Drugs |

| The FDA has historically not been involved with drug pricing. However, in June 2017, the FDA announced its Drug Competition Action Plan. The purpose of this federal-level plan is to increase the number manufacturers producing each generic drug to increase the number of low-cost generic drugs.* As part of this effort, the agency is publishing lists of off-patent, off-exclusivity brand drugs without generics in an effort to spur entry, and it is working to expedite the review of generics where there is limited competition.**

* Scott Gottlieb, “FDA Working to Lift Barriers to Generic Drug Competition,” FDA Voice, June 21, 2017, https://blogs.fda.gov/fdavoice/index.php/2017/06/fda-working-to-lift-barriers-to-generic-drug-competition/. ** “FDA Tackles Drug Competition to Improve Patient Access,” June 27, 2017, https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm564725.htm. |

Other state activity to prevent price increases for generic drugs focuses on the courts. Since 2014, the state of Connecticut has been investigating suspicious pricing of certain generic manufacturers. In 2017, attorney generals from 45 states, in addition to DC and Puerto Rico, brought forth allegations accusing 18 generic manufacturers and their subsidiaries of collusion. They allege that the manufacturers worked together to divide the market, and then designated companies stayed out of the bidding process for customers or placed bids that they knew would not be accepted.36 This lawsuit is pending as of the publication of this brief.

Biosimilars

One area of activity to increase use of generic drugs focuses on biosimilars, which are drugs derived from an animal or microorganism, as opposed to traditional small molecule drugs, which are synthesized in labs.37 Once the FDA approves a generic as therapeutically equivalent to a brand drug,38 a pharmacist generally can substitute a prescription for a brand name drug with a generic, unless the prescriber has explicitly written that the prescription is to be filled as written. In some states, pharmacists are required (versus having the option) to substitute a generic for prescribed brand unless otherwise stipulated.39 Because biosimilars are highly similar and interchangeable with biologics, but are not therapeutically equivalent as generic drugs are to small molecule drugs, they require new legal authority to permit their substitution for branded biologic drugs. Research indicates that the use of biosimilars can generate huge savings across all payers, including Medicaid.40 Since 2013, states have been expanding substitution laws to biosimilars.41 In 2017, eleven states enacted legislation requiring biosimilar substitution (Iowa, Kansas, Maryland, Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, New York, Ohio, and South Carolina). In February 2018, South Dakota enacted biosimilar substitution legislation.42

Increasing Pricing Transparency

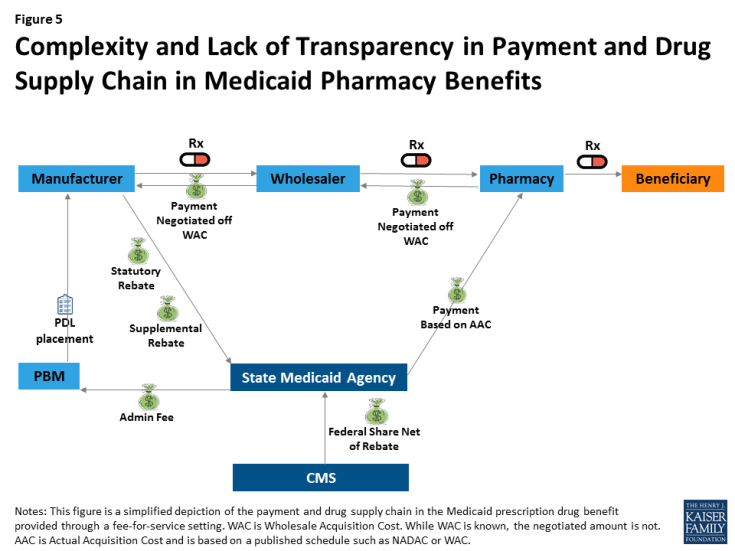

Many see drug pricing transparency as key to addressing the high cost of drug prices,43 as there are many opaque aspects to the pricing of prescription drugs in general and specifically within Medicaid. Within Medicaid (and for most other payers), payment for drugs goes through a complex process in which wholesalers pay manufacturers, pharmacies pay wholesalers, and states pay pharmacies; however, manufacturers provide rebates directly to states (Figure 5). At each point in the payment chain, there are many unknown factors affecting pricing.

Figure 5: Complexity and Lack of Transparency in Payment and Drug Supply Chain in Medicaid Pharmacy Benefits

For example, many parts of drug reimbursement are based on manufacturer-set list prices for a drug: the WAC or the less frequently used “Average Wholesale Price” (AWP).44 Manufacturers do not provide public information on how they set this list price and historically have not been required to explain changes in a product’s list price. WACs are the basis for negotiated payment between the manufacturer and wholesaler as well as the wholesaler and the pharmacy (Figure 5). In addition, WACs affect Medicaid reimbursement schedules, as they feed into the NADAC. Additionally, some states continue to use WACs when NADACs are unavailable.45 The WAC is available to the public, but it is difficult to obtain WACs efficiently on a large scale or over time without using drug pricing compendiums available for purchase. Thus, there is limited public information on a core component affecting drug pricing system-wide.

Other sources of opacity in Medicaid drug pricing stem from rebates and PBMs. Federal statutory Medicaid rebates are not available to the public at the drug level. Although the formula for calculating federal statutory Medicaid rebates is provided in statute and based on the Average Manufacturer Price (AMP) and the Best Price, neither of these prices are made publicly available.46 State supplemental rebates also are not released to the public at the drug level.47 In managed care settings, PBMs may also negotiate rebates with manufacturers (often based on the WAC).48

Although most believe it would not directly lower drug costs, some feel that increased drug pricing transparency would help policy makers better understand which prescription drugs and which parts of the supply chain are spending drivers. Transparency laws would make information that may be available only to a state Medicaid agency or PBM available to the general public and other state lawmakers.49 The public highly favors drug pricing transparency, with a recent poll finding that 86% of Americans would like drug companies to publicly release information on how prices are set.50

Several states have included public reporting as a component in broader prescription drug initiatives discussed above, and several states have passed or are considering laws primarily focused on pricing transparency. These laws vary in scope, focus of drug class, and actor, as well as how they report information.51 Laws promoting drug transparency tend to focus on manufacturers and WACs, but the pharmaceutical industry has argued that policy makers should also seek transparency throughout the supply chain.52 In some states, representatives of the pharmaceutical industry have pushed back on recently passed transparency legislation.53

Manufacturer Transparency Laws

Manufacturer transparency laws focus on making public information about WACs, which feed into prices and payment throughout the system. Vermont was the first state to pass drug transparency legislation in June 2016. It did so with the purpose of understanding drug cost drivers statewide. The Vermont law54 directs the two separate agencies55 to collaborate to identify up to 15 costly drugs from separate drug classes with large WAC increases, posting them online. The manufacturers must then provide justification for these price increases to the Attorney General, who will present findings to the General Assembly.

In October 2017, California passed a law similar to the Vermont transparency law but larger in scope. Under the California law,56 manufacturers must report to the state information for drugs with WACs greater than $40 a month with cumulative WAC increases over the course of the two years prior above specified amounts. Manufacturers also must report WAC data, as well as other information for new products that qualify as specialty drugs in Medicare. In addition, manufacturers must alert the public 60 days in advance of any drugs that will experience specified WAC increases.57 Ultimately, however, manufacturers are not required to report anything that is not already publicly available, albeit in a less accessible format. Health care service plans are also required to report annually to the state the 25 most prescribed, the 25 most costly, and the 25 drugs with the highest increase in year-over-year spending. The state will then summarize this information for public release.

In June 2017, Louisiana passed a pair of laws requiring that manufacturers make quarterly reports of WACs and that the Louisiana Board of Pharmacy post these WACs online for the public.58 Although seemingly much simpler than other laws related to WACs, the Louisiana law could create the most comprehensive, accessible, and free set of list prices for use by the public among any of the new laws.

PBM Transparency Laws

Differing from the transparency laws that focus on manufacturer pricing, some laws focus on or include PBM rebates. Nevada enacted a law59 in June 2017 that targets both manufacturer pricing and PBM rebates. The Nevada law only focuses on prescription drugs to treat diabetes, for which the list price more than doubled between 2011 and 2016 despite multiple manufacturers producing the drugs.60 In a related action, a number of lawsuits have emerged alleging insulin manufacturers of inflating list prices in an effort to generate higher PBM profits, and maintain manufacturer market share.61 In the meantime, the Nevada law specifies that manufacturers must annually provide WACs, data about the costs of producing the drug, and data about profits for all diabetes drugs to the Nevada Department of Health and Human Services. They also must provide information about factors contributing to price increases for diabetes drugs that had significant price increases over a two-year period. In addition, PBMs must report all discounts and rebates for these diabetes drugs and how theses discounts and rebates were distributed among each different payer, including Medicaid.62 The Department will provide annually a report to the public based on this information. In early 2018, a similar bill was introduced in the Colorado legislature.63

Drawing on the Resources of the Federal Government

Other programs that purchase prescription drugs, in particular federal programs, have policy levers beyond those currently available to state Medicaid programs. Some states are looking to draw on these and other resources of the federal government in their efforts to control prescription drug spending.

Aligning Prices to Federally-Negotiated Prices

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is a major purchaser of prescription drugs. Like Medicaid, the VA obtains guaranteed minimum rebates for prescription drugs, and the Department’s use of a closed formulary enables it to obtain additional rebates that lead to relatively low net prices.64 Two states, Ohio and California, have voted on privately-sponsored65 ballot initiatives that would have required that manufacturers provide additional rebates to states66 to ensure “further price reductions so that the net cost of the drug […] is the same as or less than the lowest price paid for the same drug by the United States Department of Veteran Affairs.”67 These rebates would have applied within Medicaid as well as for other state-purchased drugs (such as for state employees or through state prisons). There was confusion among the public about the effects of the proposed law68 and substantial spending from the pharmaceutical industry to oppose the initiatives.69 In addition, there was uncertainty about the states’ ability to enforce the law, whether it would impact the VA’s ability to negotiate drug prices, and the states’ ability to negotiate supplemental Medicaid rebates.70 Ultimately, the proposal was rejected by 79% of voters in Ohio and by 53% of voters in in California.71

Appeals for Federal Intervention

Perhaps reflecting a belief that they have limited policy levers, some states are directly appealing to the federal government to take action that would in turn lower state prescription drug spending. Most notably, Louisiana is considering a request that the federal government use licensing agreements and patent authority for hepatitis C DAAs. Two provisions the state is considering, based on feedback from experts in the field,72 include asking the federal government to obtain a license for DAAs voluntarily from manufacturers and requesting the federal government to use statutory authority enabling it to use patented products. The first action, which is voluntary and untested, was recommended by the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine,73 and involves manufacturers voluntarily competing with each other to license their patent to the federal government. The second action involves the federal government invoking 28 U.S.C. Section 1498, under which the federal government has the authority to use patents, in this case for DAAs, for a fair price, and then contracting with a generic manufacturer to produce the DAAs. The federal government made use of this authority many times in the 1950s and 1960s and came close to doing so for ciprofloxacin during the 2001 Anthrax scare.74 Louisiana is considering requesting using this approach for Medicaid enrollees, incarcerated individuals, and uninsured individuals, arguing that a fair compensation would lead to larger payments to manufacturers due to an increase in the number of people obtaining the drug. After opening the idea for public comment, the state is consulting with stakeholders on the idea,75 but it faces strong opposition from the pharmaceutical industry.76

Other states are appealing to the federal government for additional monitoring and study. In 2017, Illinois adopted a resolution urging the federal government to monitor the increasing costs of prescription drugs.77 In 2015, Arkansas adopted a House resolution encouraging the U.S. Congress to continue studying the causes of generic drug price increases and encouraging the FDA to review regulations to increase generic drug entry.78

Looking Ahead

As states test policies or take legal action, other states are considering what efforts succeed and could be adopted in their state. Several actions require federal approval (e.g., Massachusetts’ 1115 waiver request) or have met pushback from the pharmaceutical industry79, and states are watching these policy discussions to determine what is feasible and could be a new policy lever in controlling prescription drug spending.80 Additionally, legislation addressing transparency, generic price gouging, and methods for obtaining additional supplemental rebates have only recently gone into effect, and the effectiveness of these laws has yet to be seen. Pharmaceutical companies may decide that it is more economical to pay the penalties for failing to provide transparency data or for failing to restrain from increasing list prices than comply with the new legislation in California or Maryland. However, while some actions may be feasible for each state to take on individually, just as generic substitution laws worked their way through state legislatures in the 1970s,81 some actions, such as urging certain types of federal action, may be more effective if coming from a coalition of states.82 Meanwhile, states continue to cite the cost of prescription drugs, and in particular high-cost specialty drugs, as a budgetary concern. It is unclear whether Medicaid drug cost growth will continue to slow or whether more states will seek to target this area for cost control measures.