U.S. government (U.S.) global health efforts aim to help improve the health of people in low- and middle-income countries while also contributing to broader U.S. global development goals, foreign policy priorities, and national security concerns, including helping safeguard the health of Americans. While there is currently no standard, agreed-upon definition of global health, the National Academy of Medicine (formerly Institute of Medicine) defines global health as having “the goal of improving health for all people in all nations by promoting wellness and eliminating avoidable diseases, disabilities, and deaths.” A key dimension of global health is an emphasis on addressing inequities in health status between rich and poor countries and also for those who are most marginalized within countries, as well as a recognition that the health of people around the world is highly interconnected, with domestic and foreign health inextricably linked.

The independent source for health policy research, polling, and news.

The U.S. Government and Global Health

Published: May 28, 2024 | Updated July 29, 2024

Table of Contents

Introduction

What Is the U.S. Role in Global Health?

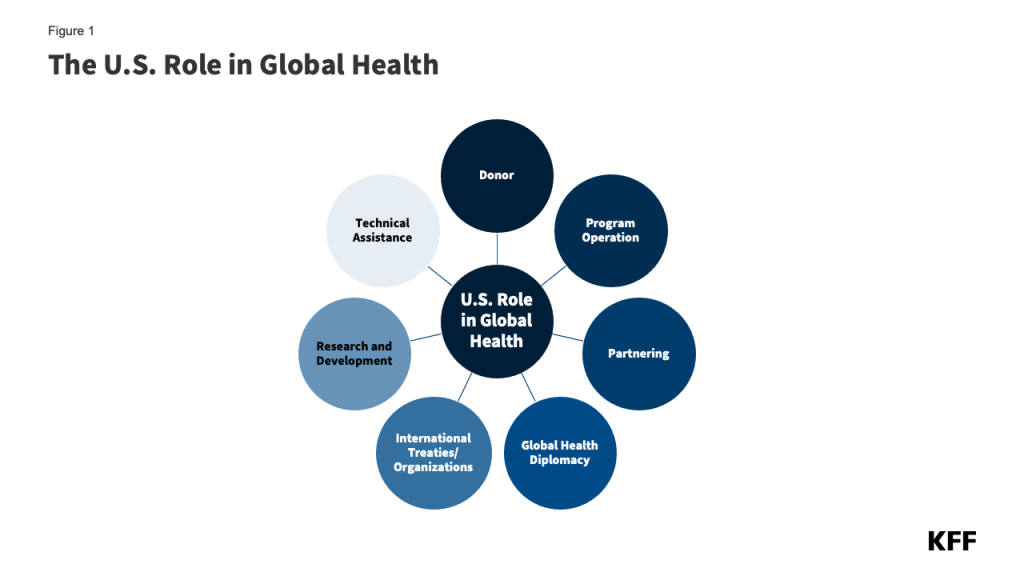

The U.S. role in global health is multifaceted and includes a broad range of activities. Its primary roles are as a supporter of bilateral (i.e., country-to-country) efforts, directly funding implementation of global health efforts in partner countries, and as a donor to multilateral health institutions (i.e., international organizations that pool support from multiple countries for one or more areas of global health). The U.S. also engages in global health diplomacy through its relationships with other governments, multilateral institutions, non-governmental organizations, and the private sector. Specifically, the U.S. government:

- acts as a donor by providing financial and other health-related development assistance (e.g. commodities, like contraceptives or bed nets for protection from disease-carrying mosquitoes) to low- and middle-income countries;

- operates programs and delivers health services;

- provides technical assistance and other capacity-building support;

- participates in major international health organizations and coordinates health efforts with other stakeholders through global health diplomacy;

- conducts research;

- supports international responses to disasters and other emergencies; and

- partners with governments, non-governmental groups, and the private sector (Figure 1).

U.S. global health activities target a variety of issues and use different intervention approaches such as:

- Health services and systems: improving basic and essential health services, systems, and infrastructure;

- Disease detection and response: supporting surveillance, prevention, and treatment of diseases, including both infectious (e.g. HIV, TB, malaria) and non-communicable diseases (e.g. cardiovascular disease, cancer);

- Population and maternal/child health: promoting maternal health; reproductive health and family planning; child nutrition, immunization, and other child survival interventions;

- Nutrition, water, and environmental health: providing non-emergency food aid and supporting dietary supplementation and food security; clean/safe water and sanitation; mitigation of environmental hazards; and

- Research and development: investigating and developing new technologies, interventions, and strategies, including vaccines, medicines, and diagnostics.

What Are the Major Global Health Program Areas the U.S. Supports?

The U.S. government (U.S.) supports global health through a wide array of bilateral and multilateral global health programs in countries around the world. Its major program areas include:

HIV/PEPFAR

While the U.S. first provided funding to address the emerging global HIV epidemic in 1986, U.S. funding and attention for these efforts has grown significantly in the last two decades, particularly following President George W. Bush’s 2003 announcement of the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), the coordinated U.S. government response to global HIV. Now the largest commitment by any nation devoted to a single disease, the launch of PEPFAR led to substantially increased U.S. support for HIV prevention, treatment, and care efforts, as well as U.S. contributions to multilateral entities, including the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (Global Fund), the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), and the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI). Today, PEPFAR’s efforts aim to ensure that populations with the highest HIV burden – particularly children, young women and adolescents, young men, and key populations— know their HIV status, receive prevention and treatment services, and become virally suppressed.

Tuberculosis (TB)

Since the 1998 launch of USAID’s global TB control program, the U.S. response to global TB has expanded, particularly after 2003 when PEPFAR highlighted the U.S. government’s commitment to addressing TB. Today, these efforts focus on diagnosis, treatment, and control of TB (including multi-drug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant TB, or MDR/XDR TB) as well as on research. The U.S. is also a donor to the Global Drug Facility of the Stop TB Partnership.

Malaria/PMI

Engaged in malaria work since the 1950s, today the U.S. supports expanded malaria efforts in low- and middle-income countries through the President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI), launched in 2005, as well as through research and other activities. PMI programs center on expanding coverage of six key high-impact interventions to control or eliminate malaria, which include: diagnosis of malaria and treatment with artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs), entomological monitoring, intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy (IPTp), indoor residual spraying (IRS) with insecticides, insecticide-treated mosquito nets (ITNs), and seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC). The U.S. is also engaged in the RBM Partnership to End Malaria.

Maternal and Child Health (MCH)

Involved in efforts to improve MCH since the 1960s, today U.S. global MCH activities aim to bring to scale a range of high-impact interventions that mitigate maternal, newborn, and under-five deaths; prevent and address the indirect causes of such deaths (such as HIV, TB, and malaria); strengthen integration of maternal health services with family planning; improve equity of access to and use of services by vulnerable populations; and strengthen health systems. The U.S. is also a donor to global organizations and initiatives addressing MCH, such as Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), and the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI).

Nutrition

For more than 40 years, the U.S. has been involved in nutrition efforts in low- and middle-income countries that aim to prevent undernutrition through support for effective interventions, such as nutrition education, nutrition during pregnancy, exclusive breastfeeding, and micronutrient supplementation. U.S. global nutrition efforts are coordinated with the U.S. Feed the Future Initiative (FtF, launched in 2009), which aims to address global hunger and food security.

Family Planning and Reproductive Health (FP/RH)

Engaged since the 1960s in international research on family planning and population issues as well as other FP/RH efforts (including the purchase and distribution of contraceptives in developing countries), U.S. global FP/RH activities are currently designed to decrease the risk of unintended pregnancies and maternal and child mortality through effective interventions, including contraception, counseling, and post-abortion care. The U.S. also provides funding to global organizations addressing FP/RH, such as the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA).

Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs)

Having historically worked on addressing NTDs through research and surveillance, attention to and funding for U.S. global NTD efforts increased markedly in 2006 with the launch of the USAID NTD Program and the subsequent announcement of expanded efforts across the U.S. government in 2008. Today these efforts focus on seven NTDs (ascariasis or roundworm, hookworm, trichuriasis or whipworm, lymphatic filariasis or elephantiasis, onchocerciasis or river blindness, schistosomiasis or snail fever, and trachoma) that are responsible for the overwhelming majority of the NTD burden but can be controlled and even eliminated with low-cost and effective interventions, such as an integrated control approach targeting multiple NTDs simultaneously through mass drug administration (MDA).

Global Health Security (GHS)

While the U.S. has supported global health security work for more than two decades, its involvement has expanded over time, with attention to these efforts growing significantly due to the COVID-19 pandemic. U.S. global GHS efforts aim to reduce the threat of emerging and re-emerging diseases by supporting preparedness, detection, and response capabilities worldwide. The U.S. has also played a key role in the development and 2014 launch of the “Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA).” Through this international partnership that now involves more than 70 countries and international organizations, the U.S. works to help countries make measurable improvements in their GHS capabilities. The U.S. is also a donor to the new Pandemic Fund, which seeks to provide sustained financing to help countries build their capacity to prevent, prepare for, and respond to epidemics and pandemics.

How Much Funding Does the U.S. Provide for Global Health?

In FY 2024, U.S. funding for global health totaled $12.3 billion. As Figure 2 shows, the U.S. investment in global health has grown significantly since the early 2000s, in large part due to funding for initiatives such as PEPFAR and PMI but with spikes in some years due to emergency or supplemental funding for disease outbreaks such as Ebola, Zika, and COVID-19. Funding reached its highest level to date in FY 2021, largely due to the U.S. global response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Although a large majority of the American public overestimates the share of the federal budget that is spent on foreign aid (with nearly half believing that the share is greater than 20%), U.S. foreign aid actually accounts for 1% or less of the federal budget, with U.S. funding for global health—which is part of the foreign affairs budget—accounting for an even smaller share.

U.S. Global Health Funding by Program Area

Looking across funding for the major global health program areas since FY 2006, most U.S. global health funding over time has been directed to HIV programs, accounting for approximately 50% of U.S. global health funding in most years (Figure 3). The Global Fund accounted for the next largest share over the period, followed by MCH and malaria. More recently, the U.S. has emphasized global health security more, with funding for these efforts increasing considerably during the COVID-19 pandemic and afterward. Consistent with this trend, most funding was provided to HIV efforts ($5.4 billion or 44%), followed by the Global Fund ($1.7 billion or 13%) and maternal and child health and global health security (both $1.3 billion or 10%) in FY 2024 (Figure 4).

Bilateral vs. Multilateral Aid

Most U.S. global health funding is provided bilaterally – that is, funding provided by the U.S. directly to or on behalf of a recipient country or region. In FY 2024, about 80% of the U.S. global health budget was provided through bilateral programs. The remainder (about 20%) is provided multilaterally through U.S. contributions to international institutions and organizations (see [“What Multilateral Health Organizations Are Supported by the U.S.?”]).

Which U.S. Agencies Are Involved in Carrying Out Efforts in These Program Areas?

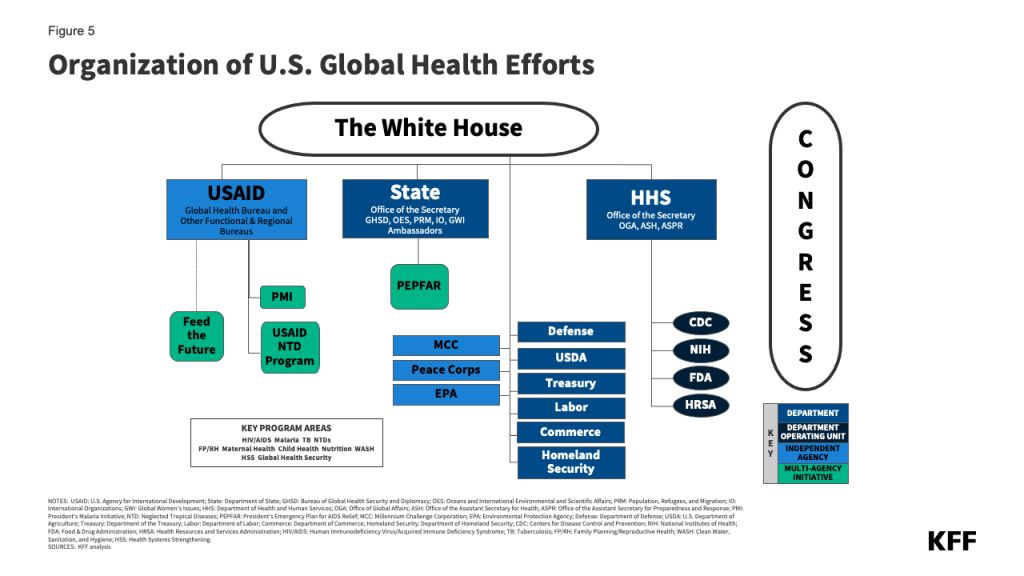

The U.S. government’s engagement in global health is carried out and overseen by multiple executive branch departments and agencies and the legislative branch, including several congressional committees (Figure 5).

Executive Branch

In general, U.S. global health engagement has developed within two main structures of the Executive Branch of government: the foreign assistance structure, which is predominantly global development-oriented and has close links to foreign policy; and the public health structure, which has its roots in disease prevention, control, and surveillance efforts.

Most funding for and oversight of U.S. global health resides within the foreign assistance structure, including:

- Department of State (State): Established in 1789, the Department of State is the Cabinet-level foreign affairs agency of the United States. It advances U.S. objectives and interests worldwide through its primary role in developing and implementing the President’s foreign policy. It also provides policy direction to USAID, the lead federal agency for development assistance. The Department of State’s new Bureau for Global Health Security and Diplomacy (GHSD) coordinates the Department’s work on global health security, including HIV, and houses PEPFAR.

- U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID): Established in 1961, USAID is an independent U.S. federal government agency that receives overall foreign policy guidance from the Secretary of State. Its role is to support long-term and broad-based economic growth in countries and advance U.S. foreign policy objectives by supporting activities through each of its programmatic functional bureaus (e.g. Bureau for Global Health) and regional bureaus. Most USAID global health programs are coordinated through the Bureau for Global Health, including HIV and other infectious diseases, MCH, nutrition, FP/RH, NTDs, and global health security.

- Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC): Established in 2004, MCC administers the Millennium Challenge Account (MCA), a U.S. government initiative providing development assistance to eligible countries to promote economic growth and reduce poverty in low- and middle-income countries. Although MCC supports several health-related programs, health is not the main focus or purpose of its work; its design is intended to link MCC contributions for development assistance (to reduce poverty through support for economic growth) to greater responsibility by low- and middle-income countries for successfully attaining certain governance and development benchmarks.

Agencies within the public health structure operate global health programs directly or in conjunction with foreign assistance agencies. They are represented most prominently by several agencies within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), including:

- Office of Global Affairs (OGA): OGA’s primary function is global health diplomacy – particularly coordinating and maintaining engagement across HHS and the U.S. government with foreign governments and ministries of health, multilateral organizations, civil society groups, and the private sector – exchanging best practices and sharing technical knowledge to advance U.S. global health priorities and research.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): With a long history of working on international health issues, CDC focuses on disease control and prevention and health promotion through operations, development assistance, basic and field research, technical assistance, training/exchanges, and capacity building.

- National Institutes of Health (NIH): One of the world’s leading research entities on global health, NIH conducts biomedical and behavioral science research on diseases and disorders to enhance diagnosis, prevention, and treatment and provides technical assistance and training. All 27 of the agency’s institutes and centers engage in global health activities.

- Food & Drug Administration (FDA): The FDA screens pharmaceutical and biological products for safety and efficacy and helps oversee the safety of the U.S. food supply.

- Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA): HRSA builds human and organizational capacity and promotes health systems strengthening to deliver care in PEPFAR countries.

In addition to the foreign assistance and public health service agencies, other departments and agencies involved in global health include the Department of Defense (DoD), the Department of Agriculture (USDA), the Peace Corps, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), the Department of Labor (DoL), the Department of Commerce (Commerce), the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR), and the National Security Council (NSC). The NSC, which sits within the White House, plays a significant role across the U.S. government, as it is responsible for coordinating and reviewing the U.S. strategy and activities related to global health security, including its international response. In addition, on matters of global health security, it works closely with the White House Office of Pandemic Preparedness and Response (OPPR), which is responsible for domestic policy coordination related to health security.

The daily operations of U.S. global health activities are administered chiefly through the Department of State’s Bureau of Global Health Security and Diplomacy (GHSD), which oversees U.S. global HIV efforts that fall under the PEPFAR program and also provides diplomatic support (through U.S. ambassadors and others) in implementing U.S. global health efforts; USAID; and HHS operating divisions, particularly the CDC. This is also reflected in the way U.S. global health funding is channeled, with most funding provided (appropriated by Congress) to the Department of State (52%), followed by USAID (33%), HHS via NIH (7%) and CDC (5%), and the Department of Defense (DoD) (2%); departments and agencies may then transfer some or all of this funding to other departments and agencies carrying out global health activities.

Legislative Branch

The U.S. Congress introduces, considers, and passes global health-related legislation; oversees global health efforts, specifying how funds for these programs are to be (and not to be) spent; authorizes and appropriates funding; and confirms presidential appointees to key U.S. global health positions. Major committees of the House of Representatives (House) and Senate with jurisdiction over global health efforts include: the House Committee on Foreign Affairs, Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, House Committee on Energy and Commerce, Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, and the Senate and House Appropriations Committees.

The U.S. global health response has been defined by numerous governing statutes, authorities, and policy decisions. For instance, the legislation that created PEPFAR in 2003 and its subsequent reauthorizations in 2008, 2013, and 2018 are key statutes of U.S. global health policy, as they govern its bilateral HIV response, bilateral assistance for TB and malaria, and participation in the Global Fund. Other statutory requirements that shape the implementation and scope of U.S. global health activities are those governing U.S. global FP/RH efforts, such as those directing how U.S. funds may not be spent. For instance, the Helms Amendment (1973) prohibits the use of foreign assistance to pay for the performance of abortion as a method of family planning or to motivate or coerce any person to practice abortion. The Kemp-Kasten Amendment (1985) prohibits funding any organization or program, as determined by the President, that supports or participates in the management of a program of coercive abortion or involuntary sterilization (it has been invoked at times to restrict funding to UNFPA).

Where Do U.S. Bilateral Global Health Programs Operate?

The U.S. provides bilateral support for U.S. global health programs in more than 70 countries, with additional countries reached through U.S. regional global health programs and U.S. contributions to multilateral organizations. Multiple factors determine where the U.S. channels its global health support. While more U.S. support is generally directed to countries facing a higher burden of disease, it is also influenced by factors such as the presence of willing and able partner governments, a history of positive relations and goodwill with host countries, strategic and national security priorities, and funding and personnel availability. The majority of countries receiving U.S. bilateral support for global health (“partner countries”) are located in sub-Saharan Africa (35 countries), followed by the Western Hemisphere (16 countries), East Asia and Oceania (11 countries), South and Central Asia (9 countries), Europe and Eurasia (4 countries), and Middle East and North Africa (4 countries) (Figure 6). Most U.S. bilateral support for global health programs is provided in sub-Saharan Africa (84%) (Figure 7). Furthermore, the top 10 country recipients of U.S. global health funding, representing about 60% of U.S. bilateral support for global health, are all in this region (Figure 8).

The U.S. typically operates more than one health program (HIV, TB, malaria, etc.) in each partner country. While in most countries, the U.S. operates programs in four or fewer global health areas, this number is generally higher in countries in sub-Saharan Africa (five or more).

What Multilateral Health Organizations Are Supported by the U.S.?

In addition to its bilateral programs, the U.S. has a long history of engagement with multilateral health organizations and international institutions, beginning with its role in the development of the first such organizations, including the Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO) in the early 1900s and the World Health Organization (WHO) a few decades later. This involvement continues with, for example, the Global Fund (which the U.S. helped to launch in 2001), Gavi (launched in 2000), the GHSA (which the U.S. played a key role in developing and launching in 2014), and the Pandemic Fund (launched in 2022). U.S. support for multilateral global health efforts takes various forms, including:

- Funding. The U.S. is often the largest or one of the largest donors to multilateral health efforts, funding core (generally used to support essential functions and operations) and voluntary (used for specific projects or initiatives the U.S. seeks to support) contributions. About a fifth (19%) of U.S. global health funding supports U.S. contributions to multilateral health organizations (Figure 9).

- Governance. The U.S. is active in the governance structures that oversee multilateral global health organizations and initiatives, including holding permanent or rotating seats on many of their boards.

- Technical assistance. The U.S. offers technical assistance in support of grants to partner countries, providing additional staff capacity to international organizations (by detailing U.S. government employees to these organizations for periods of time).

- Standard setting. The U.S. also engages in standard-setting, weighing in on global plans, treaties, and agreements to respond to a range of health issues as they are developed and considered for approval by the larger body.

Today the U.S. engages with a number of multilateral global health organizations, including health-focused specialty agencies of the United Nations (U.N.) and international financing mechanisms for global health. Key among these are eight to which Congress specifically directs funding (though the U.S. also reaches other multilateral health institutions without direct Congressional appropriations but rather through general support), of which the U.S. is the top contributor to five (the Global Fund, PAHO, UNAIDS, UNICEF, and WHO):

U.N. Agencies

- World Health Organization (WHO): WHO, created in 1948, is the directing and coordinating authority for health within the U.N. system. WHO provides international leadership on global health matters, shaping the health research agenda, setting norms and standards, providing technical support to countries, and monitoring and assessing health trends. The U.S. has been involved in WHO since its creation, providing financial and technical support as well as participating in its governance structure.

- Pan American Health Organization (PAHO): PAHO is the oldest international health agency, founded originally as the International Sanitary Bureau in 1902. The U.S. joined PAHO as a member state in 1925. PAHO, the specialized international health agency for the Americas, “works with countries throughout the region to improve and protect people’s health” and serves as the WHO Regional Office for the Americas and as the health organization of the inter-American System.

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS): UNAIDS, created in 1996 as the successor organization to the WHO Global Programme on AIDS (GPA), is the leading global organization for addressing HIV/AIDS. Coordinating efforts across the U.N. system, it is made up of 11 U.N. co-sponsors and guided by a Programme Coordinating Board (PCB), which is a subset of its co-sponsors and government representatives. The U.S. currently serves on the PCB.

- United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF): UNICEF, created in 1946, aims to improve the lives of children, particularly the most disadvantaged children and adolescents, and is one of the largest purchasers of vaccines worldwide. The U.S. was a founding member that same year.

- United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA): UNFPA, created in 1969, is the largest purchaser and distributor of contraceptives worldwide. While the U.S. helped to found UNFPA and was a leading supporter for many years, its support has fluctuated significantly over the years, due to ongoing U.S. political debates about abortion.

Non-U.N. Financing Mechanisms

- Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance (Gavi): Gavi, created in 2000, is a public-private partnership that aims to increase access to immunization in poor countries. The U.S. has been involved in Gavi since its creation through contributions, participation in Gavi’s governance, and technical assistance. The U.S. is the second largest donor to Gavi’s core programs and the top donor to Gavi’s COVAX Advance Market Commitment (COVAX AMC), a financial mechanism within COVAX that supports low- and middle-income countries through procurement and distribution of COVID-19 vaccines.

- Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (Global Fund): The Global Fund, created in 2001, is an independent multilateral financing entity that supports HIV, TB, and malaria programs in low- and middle-income countries. The U.S. was involved in creating the Global Fund and maintains a permanent seat on its Board. U.S. contributions and those of other donors are pooled and then provided by the Global Fund to country-driven projects based on technical merit and need.

- TB Global Drug Facility: The Global Drug Facility, created in 2001, is a financing mechanism of the Stop TB Partnership; it provides grants to countries for TB drugs.

U.S. support for multilateral institutions overall has fluctuated over time, reflecting, in part, changing U.S. leadership views on the relative value of bilateralism versus multilateralism. As a result, U.S. engagement in and contributions to specific multilateral health organizations and institutions may change over time. For example, the U.S. under the Trump administration did not participate in the partnership to create COVAX (an international partnership led by the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations [CEPI], Gavi, and WHO) to facilitate greater global access to the COVID-19 vaccine, although Congress did provide $4 billion in emergency funding to Gavi in support of COVID-19 vaccine access. Under the Biden administration, the U.S. joined the COVAX partnership.

Multilateral initiatives complement U.S. bilateral global health efforts, helping make progress toward U.S. goals in various program areas. In some cases, U.S. multilateral global health support allows the U.S. to reach a larger number of countries; it also may help to leverage additional funding and provide opportunities for improved coordination and technical consultations. Additionally, U.S. policies related to funding can greatly influence other financial support for multilaterals. For instance, since U.S. law requires that the U.S. contribution to the Global Fund cannot exceed 33% of total contributions from all donors, the U.S. contribution leverages other donor contributions; in effect, this requirement encourages increased support from other donors and prevents the U.S. from becoming the predominant donor to the Global Fund.

How Does the U.S. Compare to Other Donors of International Health Assistance?

The U.S. is the largest donor to global health, providing almost a third (32%) of all international health assistance among major donors and institutions (Figure 10). The Global Fund – whose top contributor is the U.S. – is the second largest donor to global health.

In addition, the U.S. has historically devoted more of its foreign assistance to health than any other donor government, contributing nearly a quarter of its foreign assistance to global health in 2022 (Figure 11). The U.S. is also the largest government donor to several specific global health areas including HIV and family planning.

Future Outlook

The U.S. has been engaged in international health activities for over a century, and today is the largest funder and implementer of global health programs worldwide. In many respects, the U.S. approach to global health will influence and impact how other countries and global entities engage in global health. Among the key issues to watch are:

- The future direction of U.S. leadership in and commitment to global health as well as its ever-evolving strategy toward global health, particularly as U.S. domestic politics increasingly impact decisions about the future of major U.S. global health initiatives (such as the short-term reauthorization of PEPFAR, which was caught up in the larger national debate related to abortion).

- Continued discussion of what U.S. global health funding levels may be going forward, particularly in a challenging U.S. political and budget environment, and whether, given likely funding constraints, U.S. global health efforts will be able to preserve or expand their reach and impact.

- Ongoing efforts to address short- and long-term impacts of COVID-19 on U.S. global health programs in partner countries while better preparing them to meet the next unexpected health challenge through heightened emphasis on building global health security capabilities.

- The appropriate balance between U.S. support for bilateral and multilateral efforts and continuing to coordinate with other donors and multilateral and international organizations, particularly in areas of renewed global concern such as updating the International Health Regulations (IHR), drafting and ratifying a Pandemic Treaty, and contributing to the Pandemic Fund.

- Ways the U.S. aims to accelerate progress across U.S. global health programs sustainably in the context of weak health systems, varied barriers to access, and challenges such as equity and legal and policy hurdles for vulnerable populations and essential health services.

- Attempts to further integrate and better coordinate across disease and program areas of U.S. global health efforts across the U.S. government.

Resources

- KFF Global Health Fact Sheets including The U.S. Government and Global Health and Breaking Down the U.S. Global Health Budget by Program Area

- U.S. Global Health Budget Tracker

- The U.S. Congress and Global Health: A Primer

- U.S. Global Health Legislation Tracker

- Key Global Health Positions and Officials in the U.S. Government

- KFF Global Health Budget Summaries

- PEPFAR Policy Resource Hub

- KFF Dashboard: Progress Toward Global HIV Targets in PEPFAR Countries

- KFF Dashboard: Progress Toward Global Malaria Targets in PMI Countries

- What Will Be the Contours of the Biden Administration’s Global Health Agenda?

- Key Issues and Questions for PEPFAR’s Future

Citation

Oum, S., Moss, K., & Kates, J., The U.S. Government and Global Health. In Altman, Drew (Editor), Health Policy 101, (KFF, July 2024) https://www.kff.org/health-policy-101-the-u-s-government-and-global-health/ (date accessed).