The Gap in Medigap

Medicare provides coverage for a wide array of medical and drug benefits, but, with its deductibles, cost-sharing requirements, and lack of an annual out-of-pocket spending limit, many people on Medicare purchase Medigap supplemental insurance to help cover their out-of-pocket costs. Roughly 11 million of the 57 million people on Medicare—around 20 percent of all beneficiaries—have a Medigap policy, which helps protect against catastrophic expenses, spreads costs over the course of the year, and simplifies medical bills and paperwork. Thanks to a 1990 federal law, people age 65 and older are able to buy a Medigap policy when they sign up for Medicare, but younger Medicare beneficiaries with disabilities are not granted the same right unless they live in a state that requires it.

Today, Medicare covers 9 million people under 65 with disabilities. Most people under 65 who qualify for Medicare must first become eligible to receive disability insurance benefits (SSDI) and then wait 24 months for Medicare coverage to begin. Given this pathway to Medicare, it may not be a surprise that younger beneficiaries with disabilities have poorer self-reported health status than seniors on Medicare, along with higher rates of cognitive impairments and functional limitations, and lower incomes, with half having income of $17,000 or less. And even with Medicare, beneficiaries under 65 with disabilities report greater difficulty accessing the care they need, sometimes because they cannot afford the cost. For some, this may be related to not having supplemental coverage, such as Medigap, to help with their out-of-pocket costs. In fact, a much smaller share of beneficiaries under 65 with disabilities than seniors have a Medigap policy (2% versus 17%, respectively), and a much higher share have no supplemental coverage whatsoever (21% versus 12%).

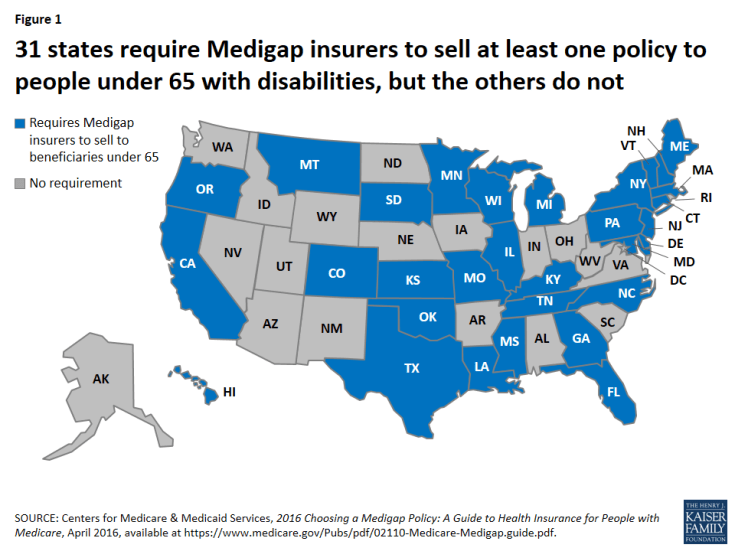

The substantially lower rate of Medigap coverage among under age 65 adults with disabilities may be due in large part to the provision in the federal law mentioned above that gives Medicare beneficiaries age 65 and older the right to purchase a Medigap policy during the first six months after they enroll in Medicare Part B and under other limited circumstances, but does not provide the same guarantee to younger people who are entitled to Medicare due to having a disability. According to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 31 states have gone beyond the federal minimum standard to require insurers in their states to provide at least one kind of Medigap policy to beneficiaries younger than age 65, but the other 19 states and DC have not (Figure 1).

Figure 1: 31 states require Medigap insurers to sell at least one policy to people under 65 with disabilities, but the others do not

In effect, the 1990 federal law created a gap in Medigap for beneficiaries under 65 with disabilities. Back then, insurers resisted the idea of providing an open enrollment period with guaranteed-issue rights to younger adults with disabilities on Medicare. At the time, many Medigap policies covered some prescription drug costs, and there was particular concern about relatively high drug spending among people under 65 with disabilities that would drive up insurers’ costs, which would lead to higher premiums.

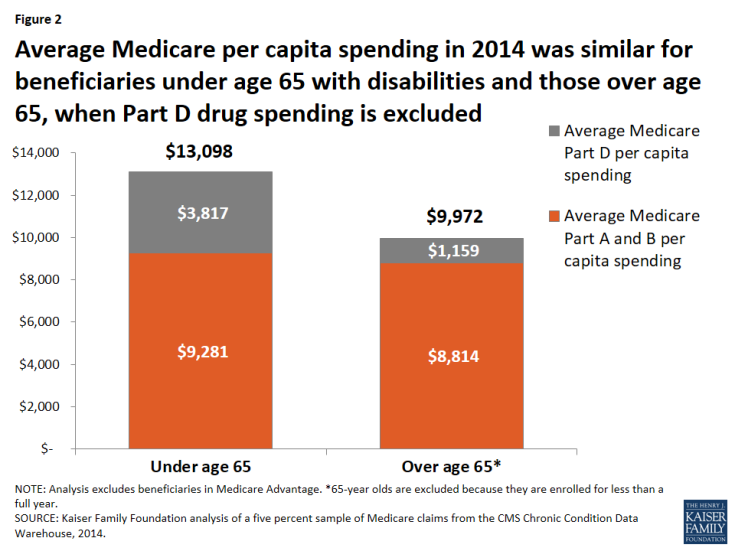

More than 25 years later, things have changed. Medigap policies sold today are prohibited from covering prescription drug costs, now that Medicare Part D provides a prescription drug benefit. This means Medigap insurers are no longer on the hook for their policyholders’ drug costs, which are indeed much higher for younger beneficiaries with disabilities than for seniors, on average, according to our research. But Medicare per capita costs are similar for younger beneficiaries with disabilities and seniors when Part D spending is excluded (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Average Medicare per capita spending in 2014 was similar for beneficiaries under age 65 with disabilities and those over age 65, when Part D drug spending is excluded

In light of these data, it’s not clear what the justification is for treating younger adults with disabilities differently from older adults when it comes to buying a Medigap policy. Revising federal law related to Medigap open enrollment rights and protections could help to reduce the gap in Medigap coverage between younger and older beneficiaries, help alleviate cost-related access problems among the relatively small but vulnerable group of people under 65 who qualify for Medicare, and provide more equitable treatment to Medicare beneficiaries across the states.