Modern Era Medicaid: Findings from a 50-State Survey of Eligibility, Enrollment, Renewal, and Cost-Sharing Policies in Medicaid and CHIP as of January 2015

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) has contributed to a significant transformation of Medicaid, broadening it as the base of coverage for the low-income population and accelerating state efforts to move from antiquated, paper-driven enrollment processes to a new modernized enrollment experience for individuals. January 1, 2015 marks the first anniversary of key ACA Medicaid provisions, including the Medicaid expansion to low-income adults and new rules for streamlined enrollment and renewal processes that coordinate across insurance affordability programs, including Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and the Health Insurance Marketplaces. Throughout 2014, states continued to develop their data-driven systems and re-engineer their business practices to fulfill the ACA’s vision. This 13th annual 50-state survey of Medicaid and CHIP eligibility, enrollment, renewal, and cost-sharing policies as of January 2015 provides a snapshot of state Medicaid and CHIP policies in place one year into the post-ACA era.

Eligibility for Adults, Children, and Pregnant Women

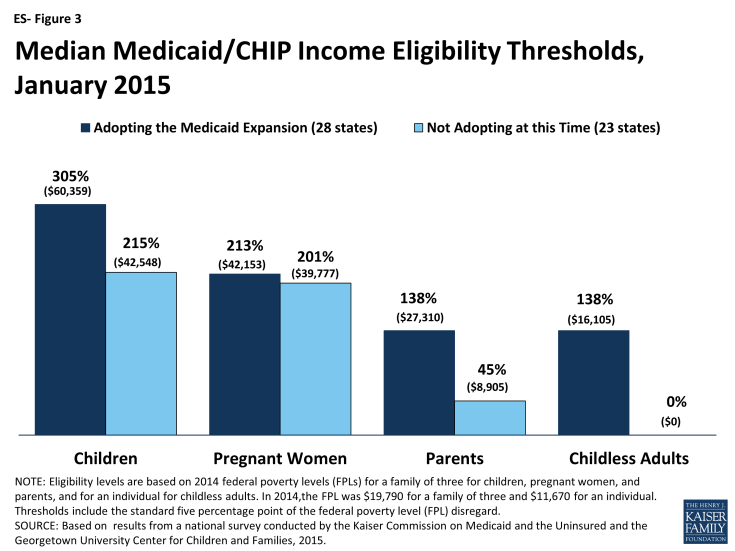

As of January 1, 2015, 28 states set their Medicaid income eligibility levels for parents and other adults to at least 138 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL), reflecting their implementation of the ACA Medicaid expansion. This count includes New Hampshire and Pennsylvania, which made decisions during 2014 to expand. Among these states, median income eligibility levels for adults have increased compared to pre-ACA levels, particularly for childless adults who were historically excluded from the Medicaid program (ES-Figure 1). There is no deadline for states to expand Medicaid, and additional states may decide to expand in the coming year.

Figure ES-1: Median Medicaid Income Eligibility Levels for Adults as a Percent of the FPL in States that Adopted the Medicaid Expansion, January 2013 and January 2015

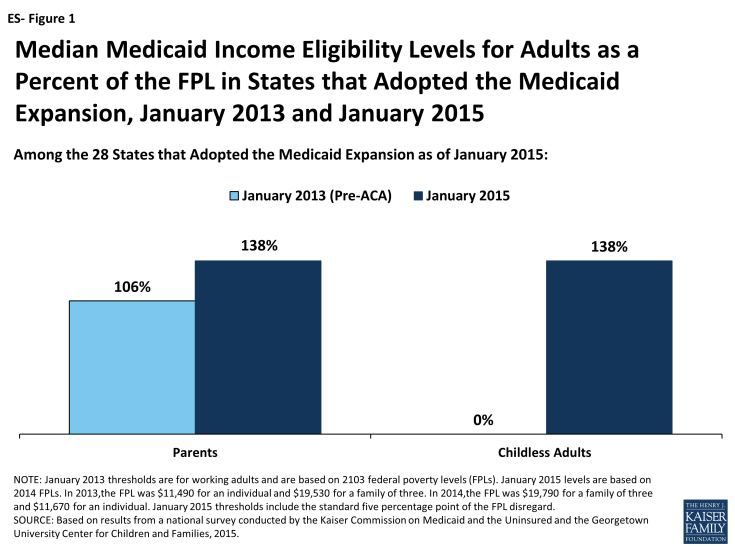

Eligibility levels remain very limited for adults in the 23 states not adopting the Medicaid expansion at this time. In all but one of these states (Wisconsin), childless adults remain ineligible for Medicaid regardless of their incomes, while Medicaid eligibility levels for parents are below poverty in 19 states (ES-Figure 2).1 In these states, many poor adults earn too much to qualify for Medicaid, but not enough to qualify for tax subsidies to purchase Marketplace coverage, which are not available to those with incomes below 100 percent of the FPL. Other Kaiser Family Foundation analysis finds that nearly four million poor uninsured adults fall into a coverage gap as a result of these limited eligibility levels.2

Figure ES-2: Medicaid Income Eligibility Limits for Adults in States Not Adopting the Medicaid Expansion at this Time, January 2015

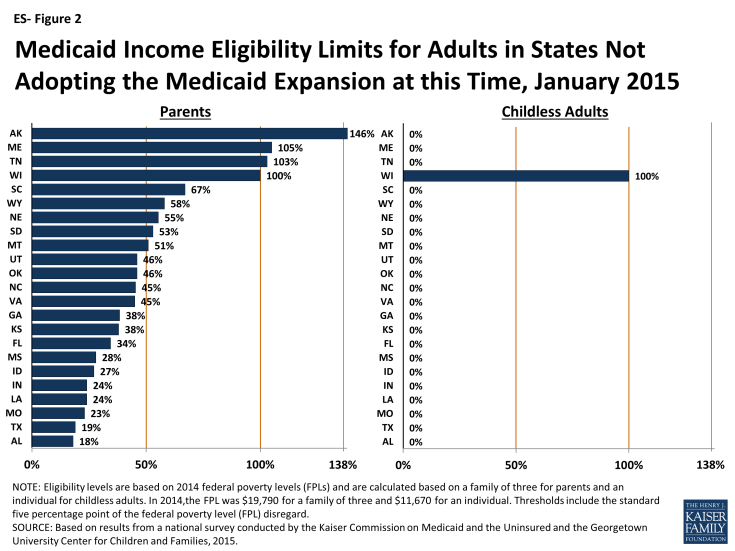

Medicaid and CHIP coverage for children and pregnant women remains strong. As of January 1, 2015, all but two states cover children at or above 200 percent of the FPL through Medicaid and CHIP with 19 states covering children at or above 300 percent of the FPL. A total of 33 states cover pregnant women at or above 200 percent of the FPL. Building on many years of progress, states also continued to take up options that expand children’s access to coverage. Consistent with the ACA’s vision of a seamless continuum of coverage options, 21 states eliminated waiting periods in CHIP, including California which transitioned its separate CHIP program into Medicaid. Illinois expanded CHIP coverage in 2013 to 317% FPL, with children above 209% FPL subject to a 3-month waiting period. Reflecting this state action, as of January 1, 2015, 33 states have no period of time that a child must be without group coverage prior to enrolling. In addition, 28 states have now eliminated the five-year waiting period for lawfully residing immigrant children, while 23 have done so for pregnant women, reflecting the recent adoption of this option in several states. Coverage for children remains protected through 2019 under ACA provisions that prohibit states from applying any restrictions in eligibility or enrollment for children.

Although eligibility levels for adults markedly increased over pre-ACA standards as a result of the Medicaid expansion, they remain well below those of children and pregnant women. Among states that expanded Medicaid, the median eligibility level for both parents and other adults is 138 percent of the FPL. However, among the 23 states that have not expanded, the median eligibility level is just 45 percent of the FPL for parents and 0 percent of the FPL for childless adults. Comparatively, the median limits for children and pregnant women are significantly higher in both expansion and non-expansion states (ES-Figure 3).

Progress Toward Streamlined Enrollment and Renewal Processes

States have achieved major progress implementing the modernized and streamlined enrollment and renewal processes under the ACA, but work continues in many areas. Reflecting this ongoing effort, the functionality of eligibility and enrollment systems is rapidly changing and improving on a week-to-week basis. Thus, what is reported here is a snapshot of processes and system capabilities as of January 2015.

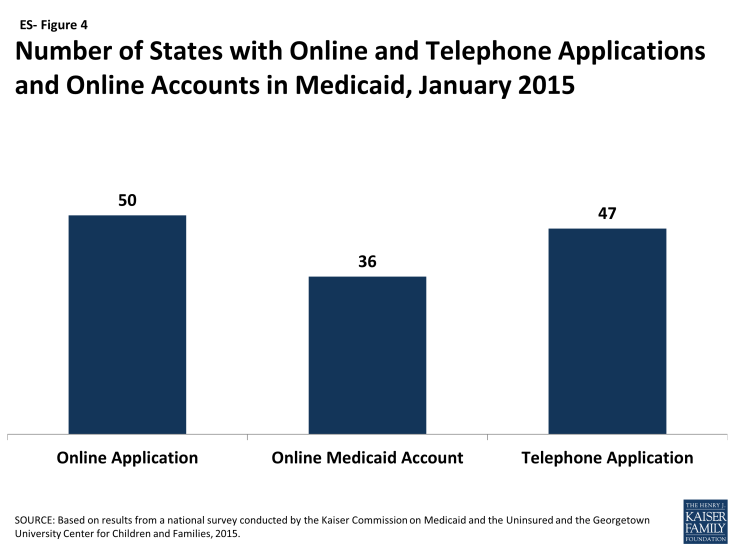

As of January 1, 2015, individuals can apply online for Medicaid at the state level in all but one state, and the majority of states are accepting Medicaid applications by phone (ES-Figure 4). Under the ACA, states must provide individuals the option to apply online for Medicaid at the state level, which currently is available in all states, except Tennessee, where individuals can only apply online through the Federally-facilitated Marketplace (FFM). Most states (36) also provide individuals the opportunity to create an online account for management of their Medicaid coverage. States continue to build features into these accounts, such as the ability to report changes, view notices, and upload documents. States also are required to provide individuals the option to apply by phone. Most states (47) accept telephone applications for Medicaid through the Medicaid agency and/or the State-based Marketplace (SBM), while the remaining states are delayed in providing this option.

Figure ES-4: Number of States with Online and Telephone Applications and Online Accounts in Medicaid, January 2015

States have established eligibility verification policies that seek to rely on electronic data and minimize paperwork for individuals. As required by the ACA, all states seek to rely on electronic data sources to verify incomes of Medicaid and CHIP applicants, with 40 states verifying income prior to enrollment and 11 verifying after enrollment. Some states are relying solely on the federal data services hub, which consolidates data from the Internal Revenue Services, the Social Security Administration, the Department of Homeland Security, and a commercial wage database, while others are tapping state data sources in addition to or in lieu of the federal data hub. For cases in which there are differences between self-reported income and data from electronic sources, two-thirds of states (33) have elected to provide a broader standard than required to consider the data to be “reasonably compatible” and accept the self-reported income. Further, most states have taken up options to minimize paperwork burdens for applicants and states by relying on self-attestation of at least some non-financial eligibility criteria, such as age, state residency, and/or household size.

Work continues to implement streamlined renewal processes. Similar to enrollment processes, the ACA also calls for highly automated, paperless renewal procedures for Medicaid and CHIP. To ease the transition to new renewal processes, CMS offered states an option to temporarily delay renewals, which 34 states took up in Medicaid and 22 states took up in CHIP during 2014. Most states have completed all renewals that were originally due in 2014, although 17 states are extending some of these renewals into 2015. However, many states are continuing work to transition to new streamlined renewal procedures and face a range of challenges, including developing system capacity, transferring data for existing enrollees from old mainframe-based systems to their new modern technology platforms, and generating notices for individuals. In the interim, a number of states are relying on mitigation strategies such as mailing forms to individuals to request the information needed to complete renewal.

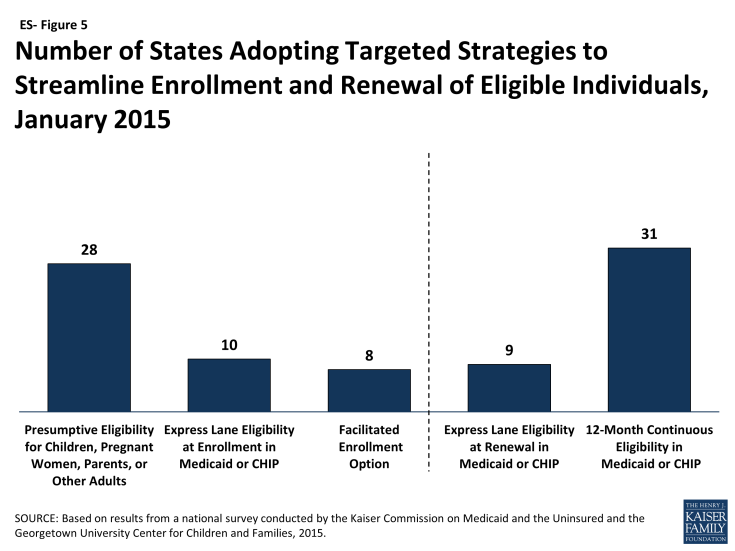

A range of additional options facilitates enrollment and renewal of eligible individuals in some states. The ACA establishes new authority for hospitals to provide temporary access to Medicaid coverage by conducting presumptive eligibility determinations while a full application is in process, which states are in varying stages of implementing. In addition, longstanding policy allows states to authorize qualified entities, such as hospitals, community health centers, and schools, to make presumptive eligibility determinations for children and pregnant women, which the ACA expanded to include parents and other adults. As of January 2015, 28 states authorize entities to conduct presumptive eligibility determinations for children, pregnant women, parents, or other adults (ES-Figure 5). Moreover, since Express Lane Eligibility (ELE) was established in 2009, states have had the option to use findings from other means-tested programs, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), to determine children eligible for Medicaid or CHIP, which ten states currently utilize. In 2013, CMS offered states additional facilitated enrollment options, including using SNAP data to identify and enroll eligible individuals and using child enrollment data to expedite parent enrollment. Eight states have taken up one or both of these strategies, which have contributed to success enrolling newly eligible adults and children and reduced administrative costs.3 In addition, to support stable coverage over time, nine states utilize ELE at renewal and 31 states provide 12-month continuous eligibility for children in Medicaid or CHIP.

Figure ES-5: Number of States Adopting Targeted Strategies to Streamline Enrollment and Renewal of Eligible Individuals, January 2015

States’ choices with regard to the integration of their Medicaid and Marketplace eligibility determination systems affect coordination across coverage programs. All states must maintain a Medicaid eligibility determination system, but states with an SBM may operate a single, integrated system that determines eligibility for both Medicaid and Marketplace coverage, which 12 states do. The remaining states have separate eligibility determination systems for Medicaid and Marketplace coverage. In states with separate systems (including all 37 states relying on the FFM for eligibility and enrollment functions and 2 SBM states with separate state-level Medicaid and Marketplace systems), electronic data, known as account transfers, must be exchanged between the systems to provide a seamless enrollment experience for individuals. During 2014, difficulties with this coordination contributed to delays in Medicaid enrollment. The federal government and states have sought to address these issues, but the extra steps needed to determine eligibility, along with the higher volume of applications during open enrollment, may still result in backlogs in some states.4

Premiums and Cost-Sharing

In general, premiums and cost-sharing remain limited in Medicaid and CHIP. As of January 2015, 30 states charge premiums or enrollment fees for children, primarily in CHIP, and 26 states have cost-sharing for children. No states charge premiums for parents or ACA expansion adults in traditional Medicaid, reflecting the fact that eligibility limits for adults in most states are below the level at which they can be charged under federal rules. However, four states (AR, IA, MI, and PA) have received waiver approval to charge monthly payments not otherwise allowed under federal rules for some adults. Most states charge nominal cost-sharing for low-income parents and expansion adults.

Looking Ahead

One year after the launch of the major Medicaid provisions of the ACA, there have been significant gains in coverage opportunities for low-income adults, most notably with increased eligibility levels for parents and childless adults in states that have expanded Medicaid. There is no deadline for states to expand Medicaid, and debate over the adult expansion will continue in some states in 2015. Medicaid and CHIP coverage for children and pregnant women remains strong across states, but without Congressional action there will not be continued funding for CHIP beyond September 2015. If CHIP funding expires, some children may lose coverage and some may face higher premiums and cost-sharing for coverage.5 The loss of enhanced CHIP funding would also have budgetary implications for states. On the operational and systems side, many states have achieved significant progress toward realizing the ACA’s vision of a modernized, streamlined enrollment system, but work continues in many areas, including establishing automated renewal processes as well as enhancing and expanding the functionalities of their systems.