Two Substantive Sides to Debate Over Obamacare’s ‘Cadillac Tax’

This was published as a Wall Street Journal Think Tank column on October 2, 2015.

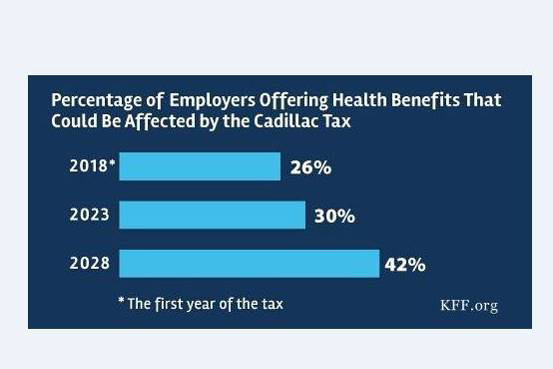

Kaiser Family Foundation post on the percentage of U.S. employers offering health benefits that could be affected by the “Cadillac tax” under the Affordable Care Act.

Democratic presidential candidates Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders and a bipartisan group from Congress have come out in favor of repealing the Affordable Care Act’s “Cadillac tax.”

Debate over the Cadillac tax on employer-provided health-care plans has been framed by some as a matter of good policy (keeping the tax) vs. good politics (repealing it to appeal to business, labor interests, and the Democratic base). As with many issues, things are not that simple. There are strong substantive arguments on both sides. Reasonable people and policy makers could disagree on pure policy grounds.

On the one hand, the current tax preference for employer-provided health benefits costs the federal government more than $300 billion per year and represents an open-ended subsidy that benefits high-wage workers more than low-wage workers while leading to more generous insurance than would otherwise be the case.

The Cadillac tax–which taxes at a 40% rate health insurance coverage that exceeds certain thresholds–would essentially cap the current tax preference. It would encourage employers to offer less generous insurance packages, constraining health spending significantly over time. Economists, many of whom strongly support the tax, predict that workers would be compensated for the reduction in health benefits with higher wages. The tax also raises $91 billion in revenues over the next decade (and even more in the decade after that), a key source of financing for the expansion in coverage under the ACA.

On the other hand, this is not the only possible approach to constraining health spending, and the Cadillac tax would hit low-income workers and the chronically ill hardest by encouraging employers to increase deductibles and co-pays. Deductibles have risen 67% since 2010, when the ACA was enacted, almost seven times faster than wages, and have generally been rising about $100 a year for people with employer policies. The Cadillac tax would accelerate that trend.

More like a Buick tax than a Cadillac tax, the levy affects more than generous health benefits negotiated by unions. As the chart above shows, approximately 26% of employers will be affected in 2018, and that share rises to 42% in 2028.

Also, while economic theory and evidence suggest that reductions in benefits will show up as higher wages, those wage increases may not be distributed equally and may not happen immediately.

When the ACA was being drafted its architects could not have known that we would be entering a period of steady growth in out-of-pocket costs for deductibles, drugs, and other services. With premium growth rates at near record lows, and with growth forecast to continue moderately, some policy makers might sensibly think this is the wrong time to impose a tax that will accelerate cost-sharing further; some might feel that the impact of cost sharing on consumers is a bigger problem for now than premium growth. Others might agree with many economists that for the long run the discipline of the tax would be the right call. The tax preference for employer-based health insurance has always raised many real issues, and they see the Cadillac tax as a way–if an imperfect one–to begin addressing them.

Whichever way this debate ends, it should not be framed as a collision between good policy and a sellout to easy politics. There are substantive arguments on both sides.