Loss of the ACA Could Greatly Erode Health Coverage and Benefits for Women

Introduction

As the Supreme Court prepares to hear the most recent challenge to the Affordable Care Act (ACA), we consider what loss of the ACA would mean for women. The broad reach of the ACA and its impact on women’s coverage is considerable, as millions have gained private or public coverage, no-cost coverage for recommended preventive services including many pregnancy-related services, caps on out-of-pocket spending, and protections against discrimination based on sex in the insurance market. The expansion of coverage under the ACA was financed in part by increases in a variety of taxes, which directly or indirectly affect women as well. All of these changes – some affecting both men and women and some affecting women specifically — are at risk in the upcoming case.

Affordable coverage options for many uninsured women will shrink as federal funding for Medicaid expansion and subsidized care are eliminated, if the ACA is overturned.

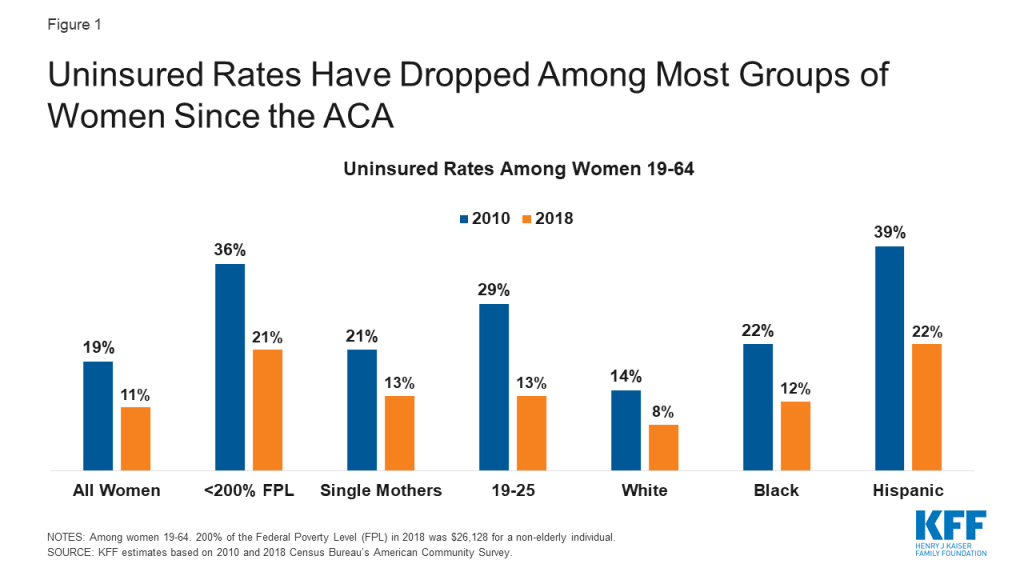

Since the ACA went into effect, the uninsured rate among adult women under 65 has declined among all demographic groups (Figure 1). This is a direct result of the ACA’s major coverage provisions: expansion of Medicaid, the subsidized plans available through the Marketplaces, and the provision that allows workers to enroll adult children up to age 26 as dependents in their parents’ employer-sponsored plans. There has also been a sharp drop in the uninsured rate among men over the past decade, but compared to women, men remain more likely to be uninsured and comprise more than half (55%) of the remaining uninsured population.

States would not be able to sustain the costs of coverage for the expanded Medicaid population, especially in the face of budgetary shortfalls arising from the pandemic. Coverage in the individual insurance market would be unaffordable to many people without federal subsidies, reversing coverage gains of the past decade and leading to a rise in uninsured women.

Gains in coverage and affordability of services for pregnancy-related care, pre- and post- partum, would be lost.

The ACA made many improvements to support care for pregnant people. In the private insurance market, the ACA established a floor for “essential health benefits” (EHB) that individual market plans must cover, including maternity care, which most non-group plans did not include prior to the ACA. Furthermore, all private plans (group and non-group) as well as Medicaid expansion programs are now required to cover routine pregnancy screenings and vitamins, at no cost under the ACA’s preventive services policy. This extends to the postpartum period as well, with all plans now required to cover lactation counseling and breast pumps without charge. The law also requires employers with at least 50 employees to provide break time and a private space for hourly workers to express milk. One study found a 10% increase in breastfeeding duration associated with coverage for breastfeeding supports and another study reported that while some women were not provided with adequate break times and private spaces to pump, those who did were twice as likely to be exclusively breastfeeding at six months.

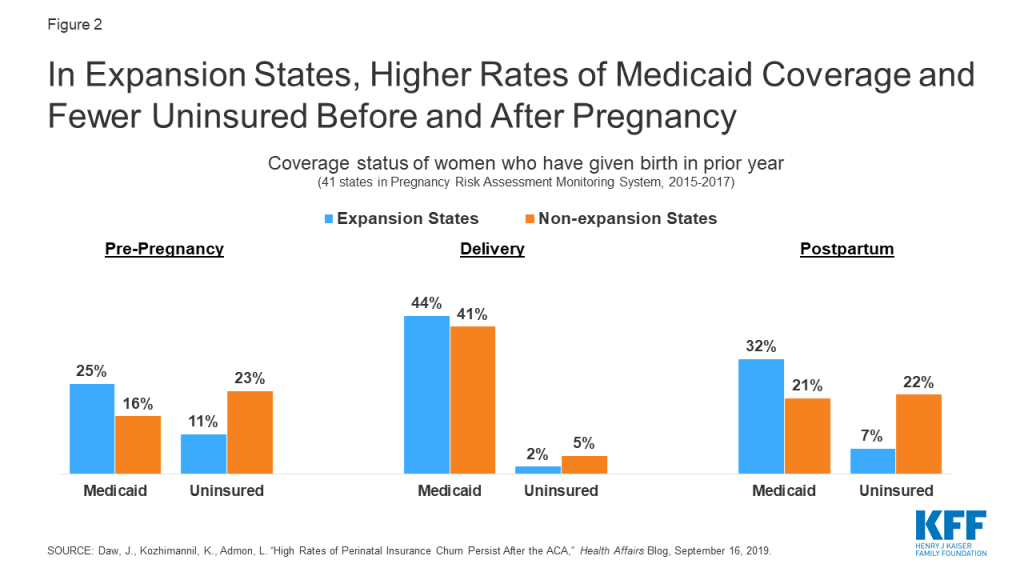

Coverage for maternity services has been required for decades in most employer-sponsored plans due to the Pregnancy Discrimination Act and under Medicaid as a mandatory benefit in all states. Nationally, the Medicaid program covers more than four in ten births and over half in several states. For low-income mothers in expansion states, Medicaid expansion has afforded greater continuity in coverage, as many can now retain Medicaid coverage because they qualify under the ACA’s higher eligibility level, whereas in non-expansion states, many women lose coverage just two months after giving birth (Figure 2). Recently, long overdue attention on maternal mortality has highlighted the importance of coverage before, during, and after pregnancy. One study found that Medicaid expansion was associated with lower maternal mortality rates compared to non-expansion states.

Health insurance plans could reinstate discriminatory policies like gender rating (charging women more than men for the same benefits), excluding maternity benefits, and denying coverage or charging more for those with pre-existing conditions.

The ACA banned a number of practices that were common among non-group insurers prior to the law. In addition to excluding benefits important for women such as pregnancy-related care, many individual market insurers charged women more than men for the same coverage, a practice called gender rating. Although gender rating affected both women and men, younger women were routinely charged more than men for plans that typically did not include maternity care. One 2012 study that reviewed gender-based differentials in individual market premiums found that reproductive age women were consistently charged higher rates than men the same age, up to 85% higher depending on the state. Conversely, the study found that among 55-year olds, some plans charged slightly higher rates to men, but the magnitude in difference was much lower compared to younger people.

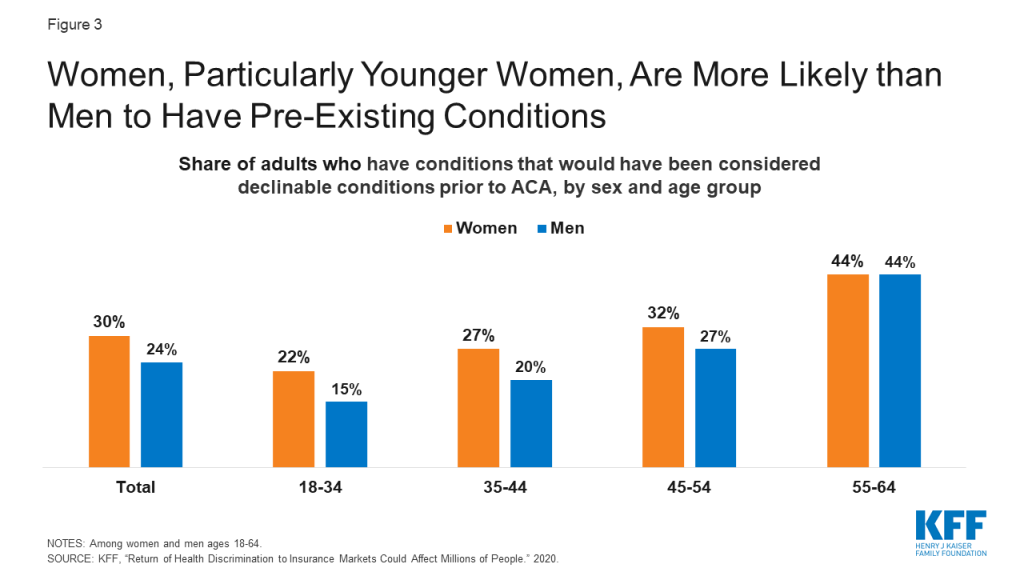

Pre-ACA, it was also routine for non-group plans to deny coverage or charge higher premiums based on an individual’s health status. We estimate that 30% of non-elderly adult women have pre-existing conditions, such as breast cancer, heart disease, or pregnancy that would have made them ineligible for purchasing an individual insurance policy before the ACA. Women have higher rates of pre-existing conditions than men, particularly during the reproductive years (Figure 3).

Affordability challenges could worsen without the ACA. The limit on annual out-of-pocket charges under private insurance might be revoked and plans could also resume charging women out-of-pocket for contraception, cancer screenings such as mammograms and colonoscopies, well woman checkups, and other preventive services.

The ACA addressed several affordability challenges experienced by women, who on average use the health system more often and have higher health expenses compared to men. Among adults and children in large employer plans, KFF analysis finds that average out-of-pocket spending is 35% higher among females compared to males. The ACA requires plans to cap annual out of pocket charges for enrollees ($8,150 for individuals and $16,300 for families in 2020). This was not required prior to the ACA, and 17% of workers covered by employer-sponsored insurance were in plans without any limit on out-of-pocket spending.

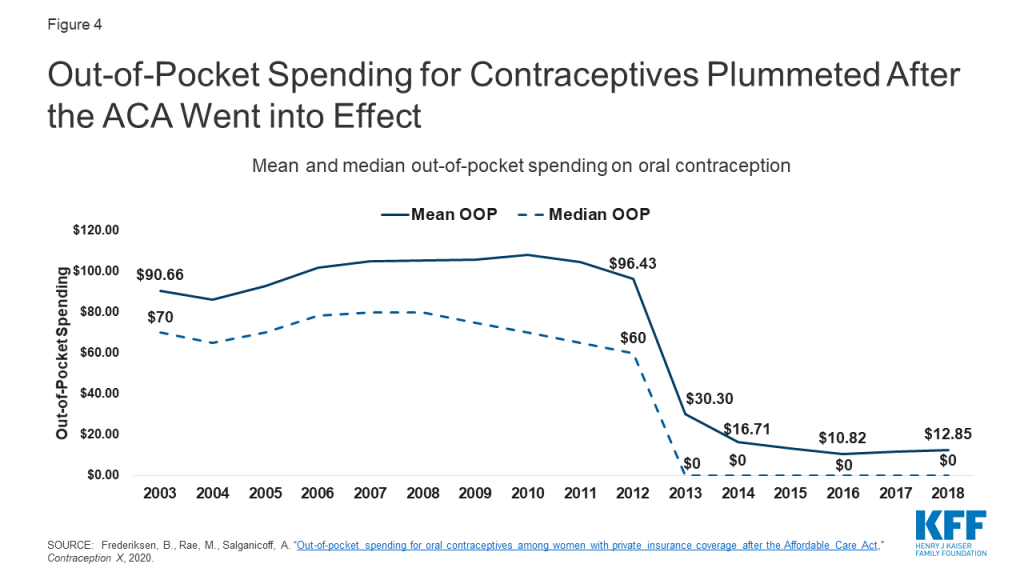

Cost protections are also integrated in the ACA requirement that all private plans and Medicaid expansion programs cover preventive services recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), the Health Resources and Services Administration, and the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, without charging cost-sharing. The slate of covered services includes many that are exclusively or disproportionately used by women, such as prenatal tests, breastfeeding services, mammograms, bone density screenings for older women, and all FDA approved prescribed contraceptives for women, including more expensive methods such as long acting reversible contraceptives (IUDs and implants). Our analysis has documented the sharp impact of the contraceptive coverage requirement, with most women now having no out-of-pocket spending for contraception (Figure 4).

Should the ACA be overturned, plans could raise the amount of out-of-pocket charges they allow, and full coverage for preventive services would no longer be required by federal law, allowing private plans to return to pre-ACA cost sharing practices. Although some states have their own requirements for contraceptive coverage and other services, state laws do not have the same reach as the ACA because they do not apply to self-funded employer plans (which cover 67% of workers with employer coverage), and many individuals would not be assisted. The loss of the ACA could make many services unaffordable and out of reach for women, who on average have higher health care expenses, lower incomes, fewer financial assets, and higher poverty rates than men.

Older women and women with long-term disabilities who are covered by Medicare may lose full coverage for preventive services and face higher out-of-pocket spending.

For Medicare beneficiaries, the ACA eliminated out-of-pocket charges for preventive services recommended by the USPSTF, such as screenings for breast cancer, osteoporosis, and depression. The ACA also added a new annual wellness visit to Medicare, which is covered at no cost to beneficiaries. Without the ACA, Medicare may return to charging 20% co-insurance for preventive services, as was the case before its enactment, meaning millions of women with Medicare would face higher out-of-pocket costs for needed preventive services.

Nearly all (94%) women covered by Medicare use a prescription medication. The ACA helped reduce beneficiaries’ out-of-pocket drug spending if they reached the Medicare Part D coverage gap, or “donut hole”, where beneficiaries were responsible for the full costs of their prescription medications prior to the ACA. The ACA gradually closed the donut hole by phasing down coinsurance charges and adding a manufacturer price discount on brand-name drugs in the donut hole. There is uncertainty around what might happen to the ACA’s coverage gap provision as a result of the Supreme Court case, since the provision was modified by subsequent legislation. However, if the ACA is struck down in its entirety, including the coverage gap provision and subsequent changes to it, that could mean an increase in out-of-pocket drug spending for women enrolled in Part D without low-income subsidies who have drug spending in the donut hole, which was the case for 15% of women enrolled in Part D in 2018.

Conclusion

This is not the first time that the Supreme Court will be deciding an ACA case with great consequences for women’s health. In the last six years, the Court has ruled on three cases about the ACA’s contraceptive coverage requirement, permitting more employer exemptions and resulting in more women losing guaranteed contraceptive coverage without cost sharing. Fully overturning the ACA would have even broader ramifications, reversing many of the important gains in coverage and the insurance reforms that have benefited women across the country.