Children’s Health Coverage: Medicaid, CHIP and the ACA

Executive Summary

Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) play an important role in providing health coverage for millions of children across the country. While the programs differ in terms of size and scope, financing and program design, together, they provide coverage to more than one in three children. In June 2013, over 28 million children were enrolled in Medicaid and another 5.7 million were enrolled in CHIP.1 This brief provides an overview of children’s coverage leading up to the implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), a review of changes for children included in the ACA, and a look at issues leading up to the reauthorization of the CHIP program. Some key findings include the following:

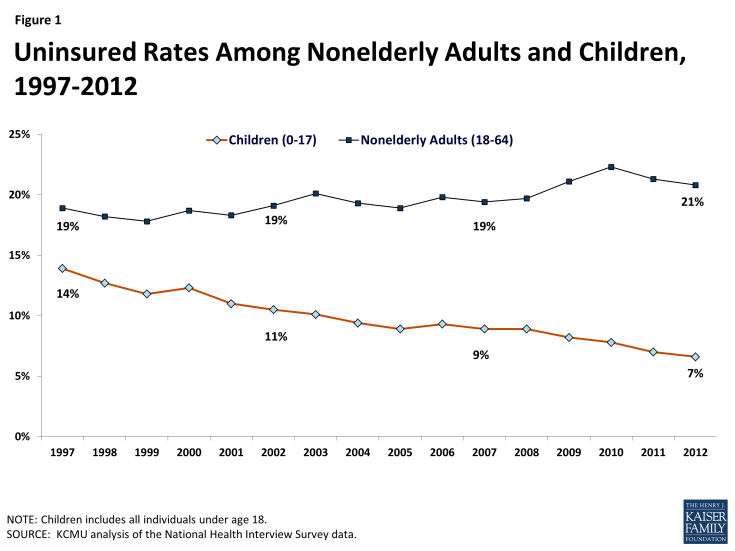

- Experience with Medicaid and CHIP demonstrate that the combined effects of eligibility expansions, enrollment simplifications and outreach efforts lead to increases in coverage and reductions in the uninsured. Over the 1997 to 2012 period the rate of uninsured children was cut in half from 14% to a low of 7%.

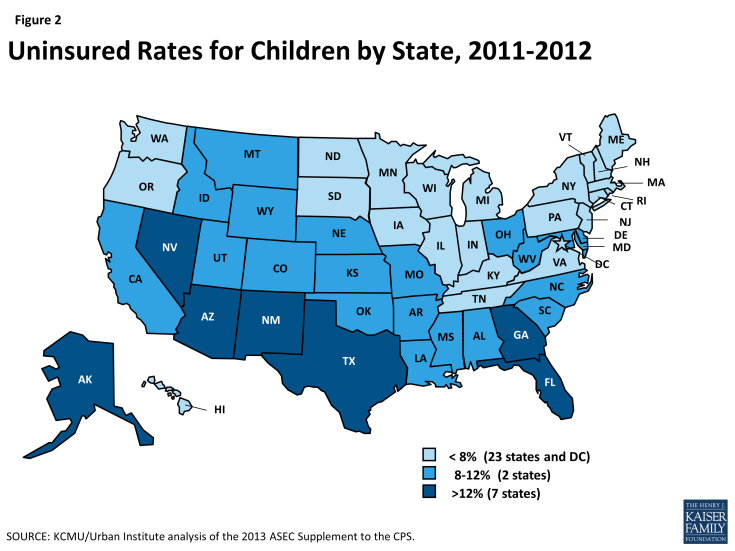

- Despite the success of Medicaid and CHIP, over 7 million children remain uninsured. Rates of uninsured children are higher in the south and the west, and nearly half of all uninsured children reside in six states (Arizona, California, Florida, Georgia, New York and Texas). An estimated 5.2 million are eligible for Medicaid or CHIP coverage but not enrolled.2

- The Affordable Care Act (ACA) provides opportunities to further increase and strengthen children’s health coverage. The ACA requires states to better align coverage for children by transitioning coverage for all children up to 133% FPL to Medicaid. The ACA also further streamlines enrollment processes, increases outreach efforts for adults which could increase enrollment of children and calls for additional financing for CHIP through FY 2015 and enhanced financing for CHIP from 2016-2019 if the program is reauthorized. New coverage options will also provide access to uninsured children through the new Marketplaces

- The future of CHIP reauthorization will have important implications for children’s coverage. Funding for CHIP reauthorization will be challenging and more research will need to highlight barriers to coverage as well as differences in coverage between CHIP and the Marketplace to understand the consequences tied to CHIP reauthorization.

- More immediately, as the ACA is implemented, ongoing outreach and enrollment efforts will be important to achieving additional coverage gains for children.

Background

Medicaid and CHIP together provide health coverage to low-income children. Both programs are jointly financed by states and the federal government and largely administered by states within broad federal rules. However, programs differ in several key ways, including size and scope, financing, benefits and cost-sharing.

Medicaid’s size and scope is broader compared to CHIP. Enacted in 1965 under Title XIX of the Social Security Act, Medicaid was created to provide health care coverage to blind and disabled individuals and families with dependent children receiving cash assistance. It has expanded over time, particularly for children, and is now an important source of health and long-term care coverage for 55 million enrollees (including 28 million children), as of June 2013. Under federal law, prior to the ACA, states participating in Medicaid were required to cover children through age 5 up to 133% FPL and school-age children up to 100% FPL. Total Medicaid spending reached $415 billion in 2012. Children represent about 20% of Medicaid spending.

Created as part of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, CHIP builds on Medicaid to provide insurance coverage to uninsured, low-income children above Medicaid income eligibility thresholds. States are permitted to use CHIP funds to create a separate CHIP program, expand their Medicaid program, or adopt a combination approach.3 In June 2013, about half of children (54%) in CHIP were enrolled in separate CHIP programs and the other half in Medicaid expansion CHIP programs.4 Compared to Medicaid, CHIP has a more limited health insurance role, covering 5.7 million low-income children with total expenditures of $10.6 billion in FY 2009.

Both Medicaid and CHIP are matching programs; however, the CHIP match rate is higher than Medicaid and CHIP financing is capped. Under both programs, the federal government matches state spending on eligible program beneficiaries according to formula that relies on states’ relative per capita income. To encourage participation among the states when CHIP was enacted, the federal government provides enhanced (relative to Medicaid) matching payments. On average, the federal government’s share of Medicaid spending is 57 percent, but it is 70 percent under CHIP. Another key difference is the financing structure and entitlement for Medicaid and CHIP. Under Medicaid, federal matching funds are guaranteed with no pre-set limits. Tied to this financing guarantee, Medicaid provides an entitlement to coverage and states are prohibited from imposing enrollment caps or waiting lists. Under CHIP federal funds are capped, nationwide, and each state operates under an allotment. Under separate CHIP programs, beneficiaries are not entitled to coverage and over time states have imposed caps and waiting lists to control CHIP spending.

Compared to Medicaid, states receive more flexibility around benefits and cost-sharing when operating separate CHIP programs. While states have considerable flexibility in designing their benefits under Medicaid and CHIP, for children, Medicaid requires certain benefits that are not required in CHIP, including Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis and Treatment (EPSDT), long-term care, services provided at Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) and many rehabilitative services. Under EPSDT, children are guaranteed comprehensive coverage including access to physical and mental health therapies, dental and vision care, personal care services and durable medical equipment, that may not be covered or may be limited in CHIP. States are generally prohibited from imposing premiums and cost-sharing for mandatory coverage of children in Medicaid, but states have more flexibility to use premiums and cost-sharing in separate CHIP programs. As of January 2013, 30 states required premiums and 27 states required co-payments for children in CHIP.5

Health Coverage of Children Pre-ACA

Experience with Medicaid and CHIP demonstrates that the combined effects of eligibility expansions, enrollment simplifications, and outreach efforts lead to increased coverage and reductions in the number of uninsured children over time. Medicaid provides the foundation of coverage for poor and near poor-children. CHIP was created in 1997 as a complement to Medicaid to provide coverage to uninsured children who were not eligible for Medicaid. CHIP, which provided states some flexibility on program design, as well as a higher federal match rate compared to Medicaid, helped spur efforts to expand eligibility to reach more low-income children, adopt strategies to simplify enrollment and renewal processes and conduct outreach and enrollment efforts. A year ahead of the implementation of the ACA, median eligibility levels for children were 235% FPL (considerably higher than coverage levels for adults) and states had adopted an array of enrollment simplification procedures to make it easier for children to obtain and maintain coverage. As a result of these combined efforts, Medicaid and CHIP have helped to reduce the uninsured rate for children to a record low of 7% in 2012. Coverage gains continued for children during the recent economic downturn when uninsured rates for adults (for whom Medicaid is much more limited) climbed (Figure 1).

While Medicaid and CHIP help fill gaps in private coverage, geographic disparities in coverage remain. A child’s risk of being uninsured varies based on where he or she lives. Across states, children’s uninsured rates range from less than 5% in six states (CT, DC, HI, MA, MI, and VT) to over 15% in two states (NV and TX) (Figure 2). Nearly half (49%) of all uninsured children live in just six states (AZ, CA, FL, GA, NY, and TX).

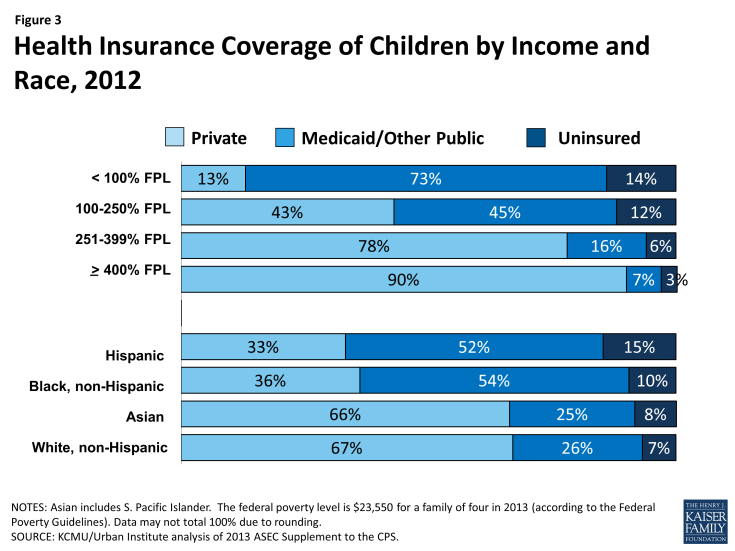

Medicaid and CHIP cover more than one in three (37%) children and play a particularly important role for all low-income children and children of color. Medicaid and CHIP are key sources of coverage for children in low-income families who often are not offered coverage through a parent’s employer and typically cannot afford the family share of premiums, even when it is offered. Similarly, Medicaid and CHIP serve as an important source of coverage for children of all races and ethnicities, and are a primary source of coverage for many children of color. Overall, the programs cover for about one in four White (26%) and Asian (25%) children, and over half of Hispanic (52%) and Black children (54%), who are more likely to live in low-income families than White children (Figure 3).

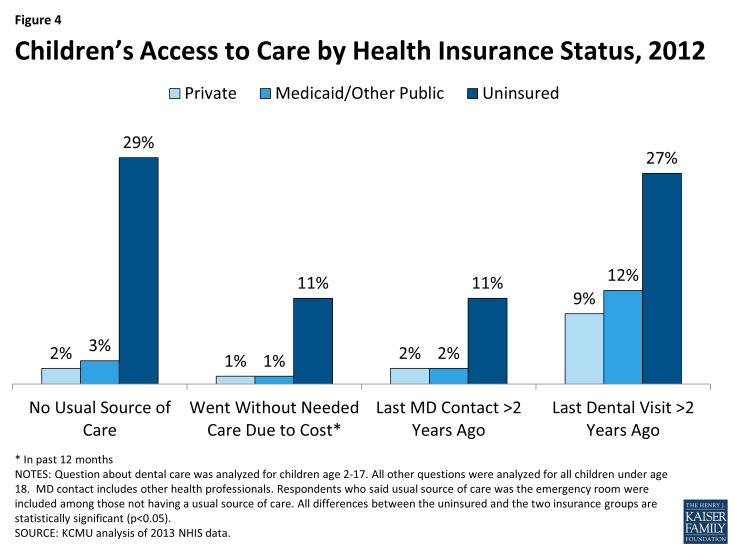

Children with Medicaid and CHIP coverage have significantly better access to care than uninsured children, and their access is comparable to privately covered children (Figure 4).6 States can implement CHIP as an expansion of Medicaid or as a separate CHIP program. Medicaid provides children with a comprehensive set of benefits, including screenings and treatments (EPSDT), check-ups, physician and hospital visits, and vision and dental care. In addition, given the limited incomes of enrollees, Medicaid significantly restricts cost-sharing requirements so families can afford care. CHIP provides a benefit package designed to meet children’s needs, although, within CHIP, states have more flexibility to charge premiums and cost-sharing and can provide a more limited set of benefits than with Medicaid. Most children (64%) enrolled in Medicaid and CHIP are served through managed care plans.7 Because children typically have low health care costs, they only account for about 20% of Medicaid program spending, even though they represent nearly half of all Medicaid enrollees.8

Health Coverage for Children Under the ACA

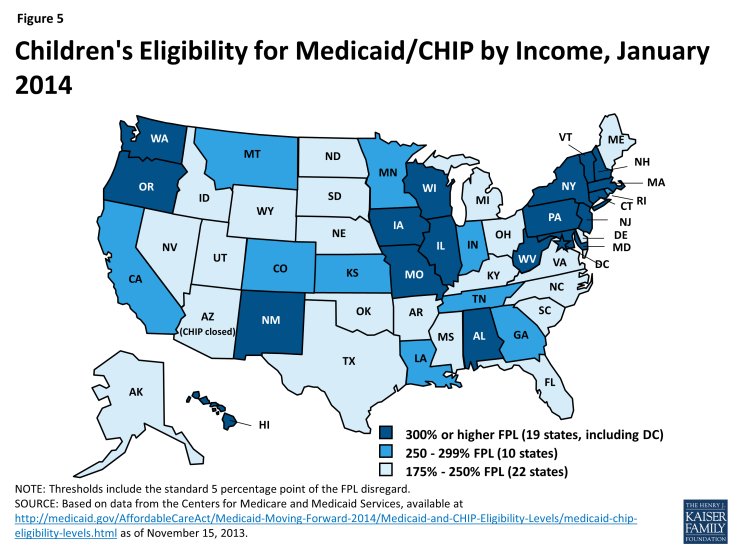

Under the ACA, eligibility for children through Medicaid and CHIP remains strong. The ACA requires states to use a uniform definition of income, called Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI), to better coordinate eligibility across health care programs. Using MAGI, more than half of the states (29, including DC) cover children in families with incomes at or above 250% FPL and 19, including DC, cover children in families with incomes at or above 300% FPL (Figure 5). The ACA protects the gains already achieved in children’s coverage by requiring states to maintain eligibility thresholds for children that are at least equal to those they had in place at the time the law was enacted through September 30, 2019.

The ACA and new guidance also help strengthen coverage for children and financing for CHIP. The ACA establishes a minimum Medicaid eligibility level of 138% FPL for all children up to age 19.9 Prior to the ACA, the federal minimum eligibility levels for children varied by age, and the federal minimum for older children ages 6 to 18 was 100% FPL. As a result of the law, 21 states needed to transition children from CHIP to Medicaid in 2014; states still receive the enhanced CHIP federal matching rate for coverage of these children. The ACA also requires that states provide Medicaid coverage to children aging off of foster care up to age 26 as of 2014.

Under the ACA, there are no waiting periods for coverage, so new guidance limits states’ ability to impose waiting periods for CHIP to three months or less starting in 2014. Prior to the ACA, to be eligible for CHIP, children had to be uninsured, so a number of states had imposed a “waiting period” to be eligible for coverage. As of December 2013, 16 of the 38 states with CHIP waiting periods have announced plans to eliminate them, and additional states may revisit this issue in their upcoming legislative sessions.10 The Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission recently recommended that Congress should eliminate CHIP waiting periods to reduce complexity and promote continuity of coverage.11 In addition, the ACA extends the CHIP program through 2015; however, the law also includes a provision that would increase the CHIP matching rates by 23 percentage points from 2016-2019 if the program is reauthorized.

Under the ACA, streamlined enrollment processes, outreach efforts and new coverage gains for parents will spur increased enrollment of children. The ACA creates a continuum of new insurance options through a Medicaid expansion to adults and tax credits to purchase coverage in newly established Marketplaces. Due to the ruling by the Supreme Court, the ACA Medicaid expansion for adults is effectively an option, but new coverage through the Marketplaces and streamlined and coordinated enrollment processes are required in all states. All of these changes are expected to result in increased enrollment of children. Beyond the requirements to streamline enrollment, CMS has also provided states with options to implement additional targeted enrollment strategies that have already been used for children to enhance coverage for adults, such as using Express Lane Eligibility, whereby states can use administrative data from other programs such as Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, SNAP or food stamps, to enroll individuals in Medicaid, and 12-month continuous eligibility. Research shows that expanding coverage for parents leads to significant increases in coverage for children and more stable coverage for children over time; studies also show that, when parents are covered, children are more likely to receive needed care.12,13,14,15

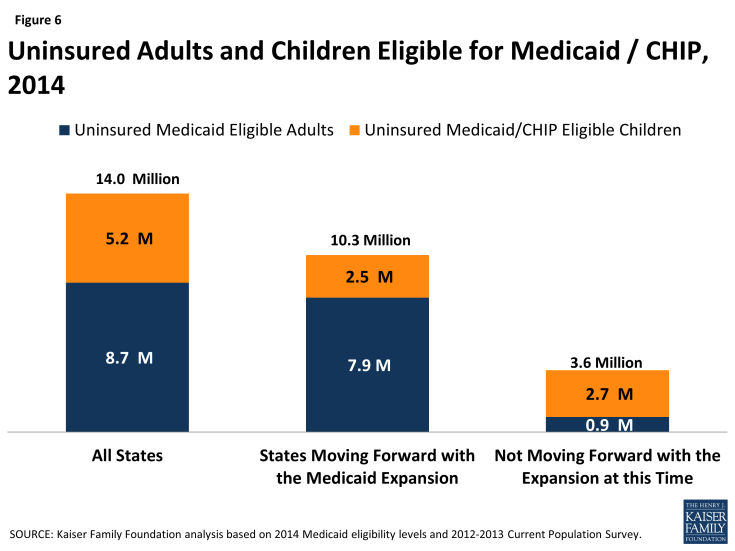

While all states have already significantly expanded coverage to children through Medicaid and CHIP, not all eligible children are enrolled in the program due to lack of parent knowledge about their eligibility and historic enrollment barriers. Over 5.2 million of the 14 million (37%) currently uninsured individuals who are estimated to be eligible for Medicaid in 2014 are children.16 In states not implementing the Medicaid expansion, children account for 75% of the uninsured eligible for Medicaid or CHIP (Figure 6).

Some currently uninsured children will gain access to new coverage options through the Marketplaces. Children in families with moderate incomes above Medicaid and CHIP eligibility limits but below 400% FPL who do not have access to affordable employer-sponsored insurance will be eligible for premium tax credits. They can use these subsidies to help offset the purchase of qualified health plans through the new Marketplaces. Overall, it is estimated that nearly half a million currently uninsured children will qualify for these new subsidies.17 Children in families with incomes above 400% FPL will also be able to access unsubsidized coverage in the Marketplaces.

Considerations for CHIP Reauthorization

CHIP reauthorization will be considered within the broader context of coverage and changes from the ACA. CHIP is funded through FY 2015, so Congress will soon need to consider CHIP reauthorization. Since CHIP was reauthorized in 2009, the ACA has altered the health care landscape by expanding Medicaid eligibility for children to 138% FPL and establishing tax credits and new options for coverage under the new health insurance Marketplaces.

If CHIP is not reauthorized, some children will face barriers to coverage. If Congress does not reauthorize CHIP, Medicaid expansion CHIP programs will be subject to the maintenance of eligibility requirements through FY 2019 and children in separate CHIP programs could transition to Marketplace coverage, if the Secretary of HHS certifies that this coverage is “at least comparable” to CHIP in terms of benefits and cost-sharing. However, some children will not be eligible for tax credits because a parent may have access to “affordable” employer coverage; however, the affordability test for employer coverage is based on a calculation of the individual coverage relative to a workers wages (not the cost of a family policy). This situation is referred to as the “family glitch” and could leave more children uninsured.

Premiums, cost-sharing and benefit differences across CHIP and the Marketplace will be considered in CHIP reauthorization debate. As noted earlier, 30 states require premiums in CHIP. Under the ACA, more adults will be eligible for Marketplace coverage. In the near-term, this could result in some families facing premiums in CHIP and the Marketplace.18 Compared to CHIP, and Marketplace coverage has higher cost-sharing requirements. A recent GAO report shows that 5 states with separate CHIP programs offered benefit packages and imposed coverage limits comparable to benchmark plans in the Marketplace, there was some variation, particularly around outpatient habilitative therapies and pediatric hearing services.19 More research is needed to understand the potential implications of these variations.

Funding CHIP reauthorization could be challenging. CHIP reauthorization will require additional federal funds; however, the increase in funds will be mitigated by the assumptions that, without CHIP, spending for Medicaid and tax credits will increase. However, since federal budget discussions are often focused on deficit reduction and new spending requires offsets, it will be challenging to finance CHIP reauthorization due to the increased CHIP matching rate included in the ACA, which increases the overall program cost. The length of the time the program is reauthorized for will also have fiscal implications.

Looking Ahead

Outreach and enrollment efforts in all states will be important for achieving sustained progress in expanding coverage to children. These efforts need to continue over the course of the year, since enrollment in Medicaid and CHIP is not limited to the open enrollment period of the Marketplaces. Even in states not moving forward with the Medicaid expansion at this time, children will be eligible for coverage through previously expanded Medicaid and CHIP eligibility levels. For children already enrolled in coverage, outreach efforts will focus on coverage retention, to reduce churning on and off of coverage. Looking ahead, the future of CHIP will have important implications for children’s coverage.

Endnotes

Vernon K. Smith, Health Management Associates, Laura Snyder and Robin Rudowitz, Medicaid Enrollment: June 2013 Snapshot and CHIP Enrollment: June 2013 Snapshot (Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Kaiser Family Foundation), https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-enrollment-june-2013-data-snapshot/ and https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/chip-enrollment-june-2013-data-snapshot/.

KFF analysis of the 2012-2013 Current Population Survey and Robin Rudowitz, A Closer Look at The Uninsured Eligible for Medicaid (Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Kaiser Family Foundation, December 2013), http://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/a-closer-look-at-the-uninsured-eligible-for-medicaid/.

According to CMS, as of January 2013, 15 states operate separate CHIP programs, 7 states operate Medicaid expansion CHIP programs, and 28 states operate combination programs, http://www.medicaid.gov/CHIP/Downloads/CHIPMap-01-14-13.pdf.

Vernon K. Smith, Health Management Associates, Laura Snyder and Robin Rudowitz, Medicaid Enrollment: June 2013 Snapshot and CHIP Enrollment: June 2013 Snapshot (Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Kaiser Family Foundation), https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-enrollment-june-2013-data-snapshot/ and https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/chip-enrollment-june-2013-data-snapshot/.

Premium, Enrollment Fee, and Copayment Requirements for Children, January 2013 (Kaiser Family Foundation, State Health Facts), https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/premium-and-co-payment-requirements/.

KCMU/Urban Institute analysis of 2012 ASEC Supplement to the CPS.

Department of Health and Human Services, 2013 Annual Report on the Quality of Care for Children in Medicaid and CHIP (HHS, September 2013), http://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Quality-of-Care/Downloads/2013-Ann-Sec-Rept.pdf.

KCMU/Urban Institute estimates based on data from FY 2010 MSIS and CMS-64.

Ibid.

Tricia Brooks and Martha Heberlein, Making Kids Wait for Coverage Makes No Sense in a Reformed Health System (Georgetown University Center for Children and Families, December 2013), http://ccf.georgetown.edu/ccf-resources/making-kids-wait-for-coverage-makes-no-sense-in-a-reformed-health-system.

Report to the Congress on Medicaid and CHIP (Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, March 2014).

Martha Heberlein, et al., Medicaid Coverage for Parents under the Affordable Care Act (Georgetown University Center for Children and Families, June 2012), http://ccf.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/Medicaid-Coverage-for-Parents1.pdf.

Karyn Schwartz, Spotlight on Uninsured Parents: How a Lack of Coverage Affects Parents and their Families (Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Kaiser Family Foundation, June 2007), https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/spotlight-on-uninsured-parents-how-a-lack/.

Leighton Ku and Matthew Broaddus, Coverage of Parents Helps Children, Too (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 2006), http://www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=754.

Putting out the Welcome Mat for Parents by Extending Medicaid Helps Children (Georgetown University Center for Children and Families, December 2013), http://ccf.georgetown.edu/ccf-resources/putting-out-the-welcome-mat-for-parents-by-extending-medicaid-helps-children/.

Robin Rudowitz, A Closer Look at The Uninsured Eligible for Medicaid (Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Kaiser Family Foundation, December 2013), http://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/a-closer-look-at-the-uninsured-eligible-for-medicaid/.

Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of March 2012 and 2013 Current Population Survey data. For more detail, see http://www.kff.org/report-section/state-by-state-estimates-of-the-number-of-people-eligible-for-premium-tax-credits-under-the-affordable-care-act-methods/.

Report to the Congress on Medicaid and CHIP (Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, March 2014). MACPAC recommended prohibiting premiums for children in families with incomes below 150% FPL to better align premium policies in separate CHIP programs with Medicaid and to avoid premium stacking or the combined effect of premiums in CHIP and Marketplace coverage for low-income families.

Information on Coverage of Services, Costs to Consumers, and Access to Care in CHIP and Other Sources of Insurance (GAO, 2013). http://www.gao.gov/products/gao-14-40.