Are Premium Subsidies Available in States with a Federally-run Marketplace? A Guide to the Supreme Court Argument in King v. Burwell

On March 4, 2015, the Supreme Court will hear oral argument in King v. Burwell, a case challenging the availability of the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) premium subsidies in states with a Federally-run Marketplace (including states with a Federally-facilitated Marketplace (FFM) and states with a Partnership Marketplace). In addition to expanding eligibility for Medicaid, the ACA increases access to affordable health insurance and reduces the number of uninsured by providing for the establishment of Marketplaces that offer qualified health plans and administer premium subsidies and cost-sharing reductions to make coverage affordable. The King v. Burwell petitioners are challenging the legality of the IRS regulation allowing premium subsidies in states with a Federally-run Marketplace as contrary to the language of the ACA. This issue brief examines the major questions raised by the King case, explains the parties’ legal arguments, and considers the potential effects of a Supreme Court decision.

Background

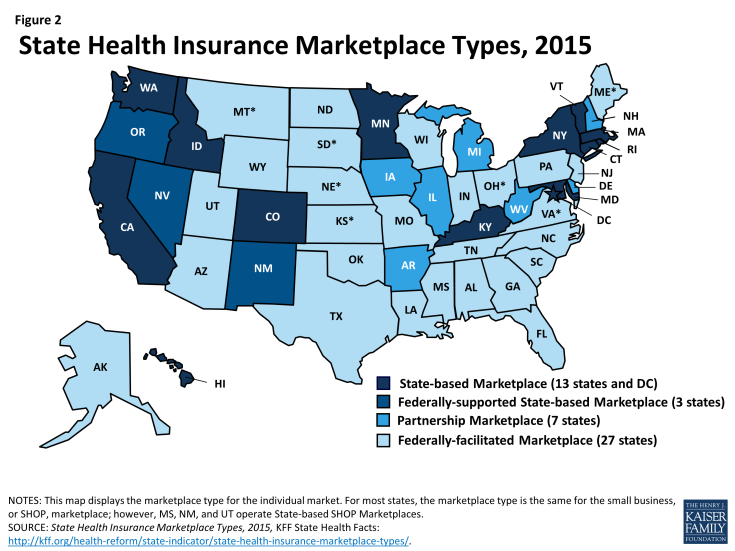

The ACA’s subsidy provisions are the central mechanism through which the law helps to make coverage affordable to individuals who purchase insurance on a Marketplace. The law provides for advance payment of premium tax credits for people with incomes between 100-400% of the federal poverty level (FPL, $11,770-$47,080 for an individual in 2015) and cost-sharing reductions for people with incomes from 100-250% FPL ($11,770-$29,425 per year for an individual in 2015). In 2015, 87% of people who selected a plan in states with a Federally-run Marketplace received premium subsidies to make their coverage affordable (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Share of People Who Selected a Marketplace Plan and Receive Premium Subsidies in States with a Federally-run Marketplace, as of February 15, 2015

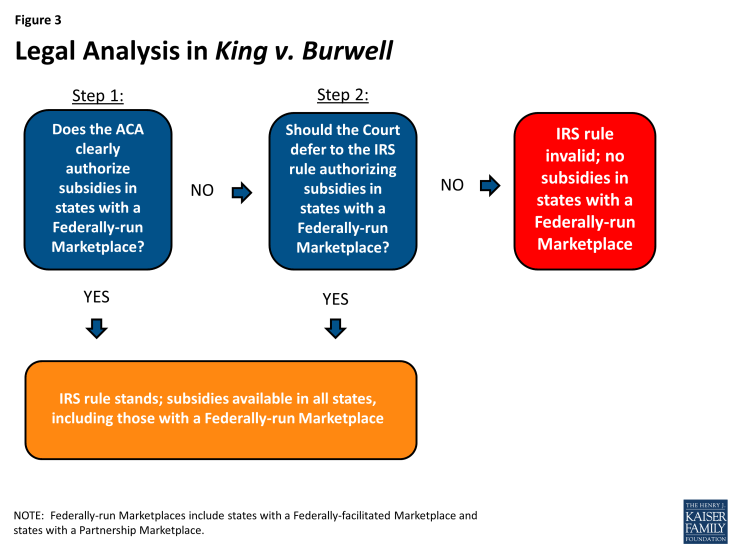

The law gives states the option to establish their own Marketplaces. A few states presently are operating federally-supported State-based Marketplaces. If states do not elect to establish their own Marketplace, the ACA provides for an FFM as a default so that Marketplaces are available in each state. States also have the option to operate a Marketplace in partnership with the federal government by assuming control over health plan management and/or consumer assistance functions. The Marketplace type in each state in 2015 is illustrated in Figure 2.

In its implementing regulations, the IRS interpreted the ACA to authorize premium subsidies for individuals who purchase coverage on all Marketplaces, including in states with a Federally-run Marketplace. The IRS rule provides that premium subsidies are available to anyone enrolled in a qualified health plan through a Marketplace and then adopts by cross-reference a U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) definition of “Marketplace” (formerly called “Exchange”) that includes any Marketplace, regardless of whether the Marketplace is State-based or Federally-run.

In addition to the subsidy provisions described above, the ACA contains private insurance market reforms, including the guaranteed issue provision, which prevents health insurers from denying coverage to people for any reason, such as pre-existing conditions, and the community rating provision, which allows health plans to vary premiums based only on age, geographic area, tobacco use, and number of family members, thereby prohibiting plans from charging higher premiums based on factors such as health status or gender. The ACA’s individual mandate requires most people to maintain a certain level of health insurance for themselves and their tax dependents in each month beginning in 2014, or pay a tax. The Congressional authors of the ACA believed that without the individual mandate and the subsidy provisions, the Marketplaces would not work effectively due to the effects of adverse selection when healthy people otherwise would choose to forego insurance.

While the ACA’s individual mandate requires most Americans to have insurance or pay a tax, certain people are exempt from the tax, including those whose annual insurance premiums would exceed eight percent of their household adjusted gross income. The ACA’s premium subsidies lower the cost of insurance for individuals and thereby subject more people to the tax for failing to satisfy the individual mandate if they do not purchase the affordable coverage available to them through the Marketplace.

The ACA also requires larger employers to offer insurance, known as the employer mandate, or pay a tax. The applicability of the employer mandate also is dependent on the premium subsidies because the associated tax is triggered when one of an employer’s full-time workers receives a Marketplace premium subsidy. If there are no subsidies, then an employer never would be subject to the tax for failure to comply with the employer mandate.

Key Questions

1. Who are the parties challenging the IRS rule?

The King petitioners are four individuals who do not want to purchase insurance in Virginia, an FFM state. They alleged that the cost of the least expensive unsubsidized Marketplace plan available to them would exceed eight percent of their anticipated 2014 income, thereby making them exempt from the ACA’s tax for failing to comply with the individual mandate. Premium subsidies reduce the cost of Marketplace coverage, making coverage affordable to the petitioners within the meaning of the ACA and requiring them to either comply with the individual mandate or pay the associated tax.

Similar cases challenging the IRS rule (described below) involve individuals who do not wish to purchase insurance as well as employers who do not want to pay the tax if their employees qualify for premium subsidies in states with Federally-run Marketplaces, including some private companies and the states of Indiana and Oklahoma. To illustrate the effect of the ACA’s premium subsidies, the DC Circuit Court of Appeals provided an example of one individual’s circumstances in the case before it: a West Virginia resident expected to earn $20,000 in 2014. Without premium subsidies, Marketplace coverage would exceed eight percent of his annual income ($1,600). With subsidies, he must purchase coverage at a cost of less than $21 per year or pay the tax for failure to satisfy the individual mandate.

2. What do the King petitioners want from the Supreme Court?

The petitioners want the Court to strike down the IRS regulation making subsidies available to individuals who purchase health plans in a state with a Federally-run Marketplace. They argue that the IRS lacks authority to issue this rule because, they contend, the ACA’s language is clear that these subsidies only are available in State-based Marketplaces. The controversy lies in the wording of an ACA provision that amends § 36B of the Internal Revenue Code: “the premium subsidy amount” is based on the cost of a “qualified health plan. . . enrolled in through [a Marketplace] established by the State under § 1311 of the [ACA].” The petitioners argue that a Federally-run Marketplace is not a Marketplace “established by the State,” and therefore the IRS has exceeded the authority delegated to it by Congress to make rules implementing the ACA. Relevant parts of the statute are excerpted in Table 1.

| Table 1: Selected ACA Provisions Relevant to King v. Burwell | |

| Citation | Statutory Language |

| ACA § 1311 [42 U.S.C. § 18031(b)(1)] |

“Each State shall, not later than January 1, 2014, establish [a Marketplace].” |

| ACA § 1321 [42 U.S.C. § 18041(c)(1)] |

If a state does not establish a Marketplace, HHS “shall establish and operate such [Marketplace] within the State.” |

| 26 U.S.C. § 36B(b)(2)(A) and (c)(2)(A) | “[T]he premium subsidy amount” is based on the cost of a “qualified health plan. . . enrolled in through [a Marketplace] established by the State under § 1311.” |

| NOTE: While the ACA uses the term “Exchange,” the term currently used is “Marketplace.” | |

3. What does the federal government want from the Supreme Court?

The respondents in King v. Burwell are federal agencies charged with implementing the ACA: HHS, the Treasury Department, and the Internal Revenue Service. The federal government wants the Court to uphold the IRS’s regulation making subsidies available in states with a Federally-run Marketplace. The federal government argues that the IRS rule is consistent with what it contends is the clear language of the ACA because a Marketplace “established by the State” also means one established by HHS standing in as a surrogate for the State. Section 1321 of the ACA directs the HHS Secretary to establish “such [Marketplace]” if a state does not create its own, and the government contends that “such [Marketplace]” is understood to be “[a Marketplace] established by the State under § 1311” (see Table 1). The government also argues that the provision authorizing premium subsidies needs to be read in the context of the whole ACA, and when looked at in its entirety, it is clear that Congress intended premium subsidies to be available to people in all states, regardless of whether the state has established its own Marketplace. While most of the government’s brief focuses on its argument that the ACA clearly authorizes subsidies in state with a Federally-run Marketplace, the government also argues that if the wording is ambiguous, then the Court should defer to the IRS’s interpretation of the statute

4. Do the King petitioners have standing to challenge the IRS rule?

To bring a lawsuit, petitioners must have legal “standing,” meaning that they actually will be harmed by the action they are challenging, and the court has the ability to order relief that will remedy the harm. Some recent news reports have questioned whether the King petitioners are in fact eligible for Marketplace subsidies and therefore whether they are legally able to challenge the IRS rule. For example, these reports allege that two of the plaintiffs may be eligible for veterans’ health coverage, which would make them ineligible for Marketplace subsidies, and another plaintiff’s actual 2014 income may have been too low to qualify for Marketplace subsidies, which start at 100% FPL. The lower courts allowed the case to proceed, and the parties’ Supreme Court briefs do not address petitioners’ standing. While the Supreme Court could raise the issue of standing, it has not ordered supplemental briefing on the question to date.

5. What did the lower courts decide in King v. Burwell and similar cases challenging the IRS rule?

In King v. Burwell, the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals unanimously upheld the IRS’s regulation providing for premium subsidies in states with a Federally-run Marketplace. The 4th Circuit observed that the ACA provision about the availability of Marketplace premium subsidies cannot be read in isolation from the rest of the statute. The 4th Circuit ruled that the ACA’s language on this point is ambiguous and therefore the IRS has the authority to reasonably interpret the ACA. The 4th Circuit also found that the IRS’s interpretation is based on a permissible construction of the statute and furthers the ACA’s broad policy goals of increasing coverage and making coverage more affordable.

On the same day as the 4th Circuit’s King decision, the DC Circuit Court of Appeals in a 2:1 decision held that the language of the ACA is clear that premium subsidies only can be provided for individuals enrolled in State-based Marketplaces. The DC Circuit found that the IRS rule contradicts the unambiguous wording of the ACA, and therefore the IRS overstepped its authority by allowing premium subsidies in states with a Federally-run Marketplace. The DC Circuit observed that when the language of a statute is clear, both the courts and administrative agencies must defer to the statute’s plain meaning. The DC Circuit also concluded that the ACA’s other provisions can continue to work without the availability of premium subsidies in states with a Federally-run Marketplace. The DC Circuit subsequently set aside its decision and announced that the entire court would rehear the case, but the rehearing was put on hold after the Supreme Court agreed to decide King.

A federal district court in Oklahoma struck down the IRS rule; the federal government’s appeal to the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals in that case is on hold pending the Supreme Court’s decision in King. Another case challenging the IRS rule is pending decision in a federal district court in Indiana.

6. Who else has weighed in on the Supreme Court arguments?

A number of amicus (“friend of the court”) briefs have been filed in support of both sides of the argument at the Supreme Court. These include members of Congress, former federal government officials, health care provider organizations, advocacy organizations, economists, and health policy and legal scholars, among others. Twenty-three states (including DC) filed an amicus brief supporting the IRS rule, and seven states filed amicus briefs challenging the IRS rule.

Among the states supporting the IRS rule, 11 have a State-based Marketplace (California, Connecticut, DC, Hawaii, Kentucky, Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, Rhode Island, Vermont and Washington), six states have an FFM (Maine, Mississippi, North Carolina, North Dakota, Pennsylvania, and Virginia), 4 states have a Partnership Marketplace (Delaware, Illinois, Iowa, and New Hampshire), and 2 states have a Federally-supported State-based Marketplace (New Mexico and Oregon) in 2015. Among the states challenging the IRS rule, six have an FFM (Alabama, Georgia, Indiana, Nebraska, Oklahoma, and South Carolina) and one has a Partnership Marketplace (West Virginia) in 2015 (Figure 2).

7. What legal analysis is the Court likely to use in deciding King v. Burwell?

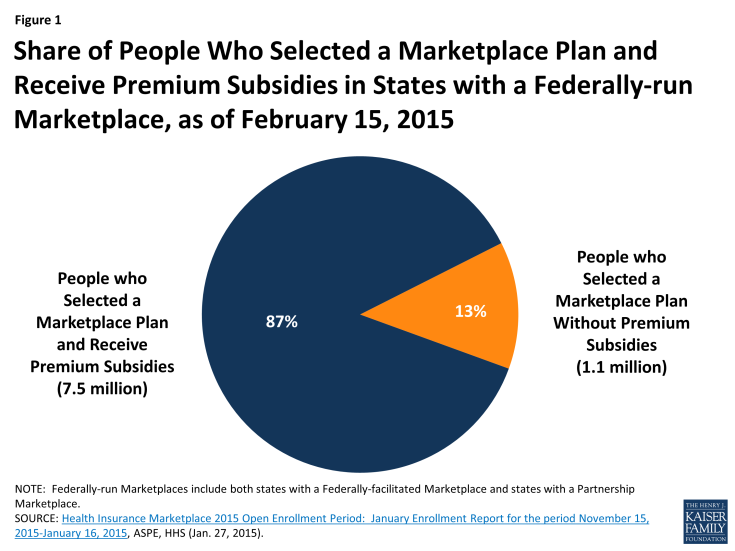

Administrative agencies have no inherent authority; because they are created by Congress, they only can act within the scope of authority delegated to them by statute. When determining whether an administrative agency’s action is valid, the Court traditionally uses a two part analysis. First, the Court asks whether the statutory language used by Congress clearly authorizes the rule issued by the agency. If the statute is clear, then Congress’s language must be followed. If the Court determines that the statutory language is ambiguous, the Court then asks whether the agency’s rule is a permissible exercise of its discretion. If the agency’s interpretation of an ambiguous statute is reasonably within its discretion, then the Court defers to the agency’s rule.

Both the petitioners and the federal government focus the majority of the arguments in their Supreme Court briefs on the first part of the legal analysis. The petitioners contend that the ACA is clear that subsidies are available only in State-based Marketplaces, while the federal government contends that the ACA is clear that subsidies are available in all Marketplaces including states with a Federally-run Marketplace. In the second part of the legal analysis, the petitioners argue that deference to the IRS’s interpretation of the statute is inappropriate, while the federal government argues that the Court should defer to the IRS’s rule. The two step legal analysis is illustrated in Figure 3, and the parties’ arguments on each issue as presented in their Supreme Court briefs are summarized in Table 2.

| Table 2: Summary of Arguments About the Legality of the IRS Rule Authorizing Marketplace Premium Subsidies | ||

| Issue | Position of Petitioners | Position of Federal Government |

| Does the ACA clearly authorize subsidies in states with a Federally-run Marketplace? | No, the ACA’s language is clear that subsidies are available only in State-based Marketplaces. | Yes, the ACA’s language is clear that subsidies are available in all Marketplaces, including states with a Federally-run Marketplace. |

| What’s the meaning of the ACA provision that refers to a “[Marketplace] established by the State”? | A Federally-run Marketplace is established by HHS, so “[Marketplace] established by the State” clearly excludes states with a Federally-run Marketplace. If Congress wanted both to be treated the same, it would have said so expressly. Instead, Congress distinctly referred to two entities that would create Marketplaces. | “[Marketplace] established by the State” is a statutory term of art that includes both State-based and Federally-run Marketplaces. It identifies the Marketplace for a particular state rather than substantively limiting the type of Marketplace. The ACA provides for a Federally-run Marketplace as an alternative way to fulfill the requirement that each state have a Marketplace because Congress could not require states to establish Marketplaces. |

| What’s the meaning of the ACA provision referring to “such [Marketplace]”? | “[S]uch [Marketplace]” means that HHS is to establish the same type of Marketplace as a state would, but subsidies turn not on the type of Marketplace but who established it. HHS is directed to establish a Marketplace “within” a state, not on its behalf. | “[S]uch [Marketplace]” means the Marketplace required by the ACA, one that the federal government establishes as a statutory surrogate for a state. Because of the Marketplaces’ central role in administering subsidies, a Marketplace without subsidies would not be a “Marketplace” within the meaning of the ACA. |

| What about reading the provision authorizing subsidies in the context of the entire statute? | Congress could have deemed a Federally-run Marketplace to be “established by the State” for subsidy purposes, but it did not do so expressly. Section 36B, which contains the “[Marketplace] established by the State” language, is the only provision that defines subsidies. | The statutory provisions cross-reference each other and must be read together. A Federally-run Marketplace could not function like a State-based Marketplace as Congress intended if subsidies were unavailable. The ACA specifically requires Federally-run Marketplaces to report on subsidies. If a Federally-run Marketplace was not the same as a State-based Marketplace, Federally-run Marketplaces would have no customers because the ACA provides that people eligible to shop on a Marketplace must “reside in the State that established the [Marketplace].” |

| What about achieving the ACA’s overall purpose? | Limiting subsidies to State-based Marketplaces incentivizes states to establish their own Marketplaces. Congress wanted to accomplish this goal in addition to providing subsidies nationwide. | Subsidies are essential to ensuring that the ACA’s nationwide insurance market reform and individual mandate provisions function. All of these provisions were designed to work together. Congress would not have provided for Federally-run Marketplaces that would fail and would not limit subsidies to State-based Marketplaces without giving states clear notice. Subsidies are provided to individuals, not to states. |

| Should the Court defer to the IRS rule authorizing subsidies in a Federally-run Marketplace? | No, the Court should not defer to the IRS rule. Congress never would have delegated such an important decision to an agency. Congressional authorization of tax credits must be unambiguous. The language providing for subsidies (§ 36B) is clear, and the IRS has no authority to interpret other sections of the ACA that are within the jurisdiction of HHS (e.g., § 1321). | Yes, the Court should defer to the IRS rule. The agency acted within the scope of its authority delegated by Congress. |

8. How is King v. Burwell different from the other ACA cases already decided by the Supreme Court?

The Supreme Court already has decided two cases about the ACA in prior terms. In National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the ACA’s individual mandate but effectively made the Medicaid expansion a state option. In Hobby Lobby v. Burwell, the Supreme Court ruled that closely held for-profit corporations do not have to comply with the ACA’s contraceptive coverage requirement in their employee health plan benefit packages if their owners have religious objections. A series of lawsuits filed by religiously affiliated nonprofit employers challenging the ACA’s contraceptive coverage requirement remain pending in the lower federal courts and may be reviewed by the Supreme Court in a future term.

In King v. Burwell, the Court will determine whether the IRS has the legal authority from Congress to interpret the law as it did in issuing its regulation implementing the ACA’s premium tax subsidies in all Marketplaces. While invalidation of the IRS regulation could have significant policy implications for how the ACA’s Marketplaces work in states with a Federally-run Marketplace (discussed below), King is not a constitutional challenge to the ACA, and the Court’s decision will not strike down other parts of the law. In addition, the King case focuses on the ACA’s Marketplace subsidies and will not affect the ACA’s Medicaid expansion provisions.

9. What are the implications if the Supreme Court rules for the federal government?

If the Court upholds the IRS rule, subsidies will continue to be administered through all Marketplaces. Despite the lower court decisions to date, the IRS rule authorizing premium subsidies in all Marketplaces remains in effect, and premium subsidies currently remain available for all individuals regardless of whether they enroll in a plan in a State-based Marketplace or in a state with a Federally-run Marketplace.

10. What are the implications if the Supreme Court rules for the petitioners?

The Court’s decision about the availability of premium subsidies in states with a Federally-run Marketplace could affect the number of people who ultimately have access to affordable coverage under the ACA. As of 2015, 14 states (including DC) have elected to set up their own Marketplaces and three states have a federally-supported State-based Marketplace; the remaining 34 states could be affected by the King decision, including 7 states with a Partnership Marketplace, and 27 states presently relying on an FFM (Figure 2).

If the IRS rule is overturned by the Court, people in the 27 states presently relying on an FFM and the seven states with a Partnership Marketplace would lose access to subsidies. Nearly 7.5 million people who selected a plan to date for 2015 in a state with an FFM or Partnership Marketplace qualified for premium subsidies (Figure 1), and it is estimated that over 12.5 million people are eligible for premium subsidies in states with an FFM or Partnership Marketplace. Without premium assistance, the vast majority of these enrollees would likely drop their coverage because they could not afford the unsubsidized cost, resulting in severe and perhaps fatal disruption to the individual insurance markets in these states.

Overturning the IRS rule also would essentially nullify the requirement that large employers offer coverage to full-time employees in these states. The penalty associated with the employer mandate is triggered when a full-time employee is not offered employer-sponsored coverage and qualifies for a Marketplace premium or cost-sharing subsidy. If Marketplace subsidies are unavailable in states with a Federally-run Marketplace, the penalty against a large employer that does not offer coverage cannot be triggered.

Looking Ahead

The Court will hear oral argument in King v. Burwell on March 4, 2015, and a decision is expected by the end of the current term in June 2015. The case will give the Court an opportunity to closely examine the language that Congress used when enacting the ACA. The fact that there is not universal agreement about whether subsidies are authorized in states with a Federally-run Marketplace could portend a finding that the statutory language is ambiguous. Or, a majority of the Court could conclude that the statute is clear. If the IRS rule is invalidated, millions of people who obtained affordable coverage under the ACA in states with a Federally-run Marketplace will be at risk of becoming uninsured without further action on the part of federal and state policymakers. For this reason, many people around the country will be awaiting the Supreme Court’s determination about the meaning of this provision of the ACA.