In 2005, Hurricane Katrina wreaked havoc on the health system in Louisiana, shuttering major safety-net hospitals in New Orleans and decimating access to care for low-income and uninsured populations. Currently, Louisiana is experiencing changes to its health care delivery and payment systems as the state expands Medicaid, provides new coverage options through the federal health insurance marketplace, and streamlines application and enrollment processes for coverage programs. This fact sheet provides an overview of resident socio-demographic characteristics, population health, health coverage, and the health care delivery system in Louisiana both pre-Hurricane Katrina and in the era of health reform.

Demographics

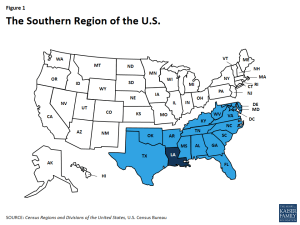

Louisiana is home to more than 4.5 million people, making it the 25th most populous state in the U.S and 10th most populous in the South.1 It is bordered by four states and is one of seventeen states located in the country’s Southern region (Figure 1). Louisiana’s topography is mostly flat but defined by the Mississippi River Delta where the Mississippi River enters into the Gulf of Mexico and salt marshes that run along the Gulf of Mexico coastline.2

Much of Louisiana is rural, but the population is concentrated in a handful of counties. Among the state’s 64 parishes (Louisiana counties are called parishes), three had total nonelderly populations that exceeded 300,000 (East Baton Rouge, Jefferson, and Orleans), accounting for over one-quarter of the state’s population (Figure 15, Appendix).3

Louisiana is racially and ethnically diverse. While people of color account for 41% of the state’s population compared to 39% of the national population, the make-up of the minority population is different from the national landscape (Figure 2). In particular, compared to the U.S. overall, a much larger share of Louisianans identify as Black (31% vs. 12% nationally).4 Hispanics account for 6% of the population in Louisiana, which is less than the share in the U.S. overall (18%). Over half of Louisiana’s population (58%) identifies as non-Hispanic White.

Other socio-demographic population patterns in Louisiana, including citizenship status and age distribution, mirror other states in the South and the U.S. overall (Table 1). Over one-quarter (26%) Louisiana residents are children, more than nine in ten (95%) are U.S.-born citizens, and almost one-quarter of nonelderly adults (22%) have at least a college degree. Nearly two-thirds of residents (65%) live in a household with at least one full-time worker.

| Table 1: Selected Demographic Characteristics of the Louisianan Population, Compared to the South and U. S. Overall, 2014 |

|||

| Louisiana | South | U. S. | |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| White | 58% | 58% | 62% |

| Black | 31% | 19% | 12% |

| Hispanic | 6% | 17% | 18% |

| Other Race/Ethnicity | 5% | 6% | 8% |

| Age | |||

| 0-18 | 26% | 25% | 25% |

| 19-64 | 62% | 61% | 61% |

| 65+ | 12% | 14% | 15% |

| Citizenship Status | |||

| U.S.-Born Citizen | 95% | 88% | 87% |

| Naturalized Citizen | 2% | 5% | 6% |

| Non-Citizen | 3% | 7% | 7% |

| Educational Attainment of Adults (19 and older) | |||

| Less than High School | 15% | 13% | 11% |

| High School Graduate | 35% | 31% | 30% |

| Some College/Assoc. Degree | 28% | 28% | 29% |

| College Graduate or Greater | 22% | 28% | 30% |

| SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation estimates based on the Census Bureau’s March 2015 Current Population Survey (CPS: Annual Social and Economic Supplement). | |||

Population Health

Louisiana falls well below national averages in rankings of state population health. Louisiana ranks 50th overall among the 50 states in the United Health Care Foundation’s report, America’s Health Rankings 2015.6 In the Commonwealth Fund rankings of state health system performance, Louisiana maintained a very low ranking of 48th among 51 states (including DC) between 2009 and 2015.7 According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), compared to other states, Louisiana has relatively higher rates of diseases of the heart, HIV, and drug-related mortality compared to national averages.8 The teen pregnancy rate has been steadily declining to 69 pregnancies per 1,000 women aged 15-19 in 2010 from 108 per 1,000 in 1992. However, Louisiana’s 2010 teen pregnancy rate still remains well above national levels (69 vs. 57 pregnancies per 1,000.9) At 483.4 cases per 100,000 people, Louisiana had the fourth highest cancer incidence rate nationally and third highest among states in the South in 2012. The state also ranked fourth both nationally and among states in the South with a cancer death rate of 190.5 deaths per 100,000 people.10

Along with states across the nation, Louisiana is experiencing a high number of drug overdose deaths. According to the CDC, the age-adjusted rate of drug overdose deaths in Louisiana in 2014 was 16.9 per 100,000, higher than the national rate of 14.7 per 100,000. However, unlike the 6.5% national increase in drug overdose-related deaths between 2013 and 2014, the rate in Louisiana decreased by 5.1% over that same period.11

Disparities in health and health care access exist in Louisiana. As in other states across the country, measures of health status in Louisiana vary by race/ethnicity, and patterns across these measures in Louisiana are similar to national data (Table 2). Over one quarter (28%) of Black residents in Louisiana report being in fair or poor general health compared to 19% of those who identify as White and 14% of those who identify as Hispanic. Additionally, Blacks (74%) are more likely to be overweight or obese than Whites (67%) and Hispanics (66%). Disparities in access to care also exist in Louisiana. As at the national level, Hispanics in Louisiana are more likely to report having no personal doctor (37%) compared to Blacks (31%) and Whites (22%).

| Table 2: Selected Measures of Health Status and Health Access for Adults by Race/Ethnicity in Louisiana Compared to the United States, 2014 | ||||||

| Share reporting that they: | Louisiana | United States | ||||

| White | Black | Hispanic | White | Black | Hispanic | |

| Have fair or poor general health | 19% | 28% | 14% | 15% | 22% | 26% |

| Smoke | 24% | 25% | 20% | 18% | 20% | 14% |

| Are overweight or obese | 67% | 74% | 66% | 63% | 73% | 70% |

| Have no personal doctor | 22% | 31% | 37% | 18% | 24% | 41% |

| Have not had a checkup in the past 2 years | 14% | 11% | 20% | 17% | 11% | 22% |

| Had mental distress in the past month | 33% | 34% | 36% | 34% | 35% | 34% |

| Have diabetes | 10% | 15% | 9% | 10% | 15% | 11% |

| NOTE: Data for Whites and Blacks exclude Hispanics. Adults are anyone 18 years or older. Mental distress indicates respondents reported that their mental health was not good at least one day out of the past 30 days. SOURCE: KCMU analysis of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) 2014 Survey Results. |

||||||

State and local efforts are working to address health disparities in Louisiana. Louisiana’s Bureau of Minority Health Access & Promotions was established by the Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals and the Minority Health Affairs Commission in 1999 to address public health issues for minority populations and poor Whites.12 In 2015, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health awarded Louisiana a five year grant, supporting collaborations between the local, state, and national communities to develop and implement effective policies supporting obesity and overweight health statuses prevention in minority communities and increase access to physical activities and healthy food choices.13 Research institutions in the state are also working to study and improve health equity across Louisiana. For example, the Louisiana Center for Health Equity is working to eliminate health disparities rooted in poverty, lack of access to quality health care, and unhealthy environmental conditions.

State Economy, Budget, and Medicaid

The recent decline in oil prices has caused economic and fiscal pressures in Louisiana. Louisiana, like most other states, saw economic conditions slowly improve following the Great Recession. In 2014, Louisiana’s total state Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was $251.6 billion, making it the 23rd largest economy in the country14, but the state experienced slower growth between 2013 and 2014 than the national average (2.7% vs. 4.1% increase in GDP between 2013 and 2014). Unlike the health care and social assistance sectors, which together accounted for over one-tenth (14%) of the total increase in GDP between 2013 and 2014, the state saw a nearly double digit decline in GDP from the oil and related sectors during this period as oil prices declined.15 In contrast to the national level, unemployment rates increased from 5.5 percent in January 2014 (a post-recession low and below the national average) to 7.0 percent in November 2014 (above the national average at that point.) The unemployment rate has declined since then but remains above national levels (6.3% vs. 5.0% in April 2016).16 The decline in economic activity in the oil and related sectors has also resulted in declines in severance tax revenues (which in Louisiana make up nearly 10 percent of state tax revenues); total state tax revenues in Louisiana have started to decline as has been the case in other oil-dependent states.17

Governor Edwards, who took office in January 2016, indicated the state faced a budget shortfall for this current fiscal year (FY 2016) and as well as for FY 2017 that was caused in part by the decline in oil prices as well as other actions taken in prior years related to revenues.18 He called a special session to address the issue in February 2016 that resulted in some measures to close part of the shortfall that included spending cuts and limited revenue increases.19 The general session, scheduled to end June 6, is considering cuts to the Department of Health and Hospitals as well as the Taylor Opportunity Program for Students (TOPS) that provides scholarships to students. The governor has indicated that he may convene another special session to explore additional revenue options.20

Medicaid and the State’s Budget

Medicaid spending accounted for over one-quarter (27%) of total (both state and federal) state budget spending in state fiscal year (SFY) 2014 (Figure 4). Medicaid is the second largest category of state general fund spending behind elementary and secondary education and is the single largest source of federal funds flowing into the state. Medicaid costs are shared by the state and the federal government, with the federal government paying more than half (63%) of Louisiana Medicaid expenditures.21 For every dollar that Louisiana spends on Medicaid, the federal government sent $1.56 in matching funds to the state in fiscal year 2014.22

While a majority of Medicaid enrollees in Louisiana are children and nonelderly adults, the elderly and people with disabilities account for a disproportionate share of the program’s expenditures. As of FY 2011, children made up 53% of Medicaid enrollees in Louisiana but accounted for just under one-quarter (23%) of total Medicaid expenditures (Figure 5). The elderly and people with disabilities accounted for over one-quarter (27%) of enrollees but 65% of total program costs. Average spending per beneficiary in Louisiana was $4,869, the sixth lowest in the South and much lower than the national average of $5,790 (Figure 6).

Following national trends, Louisiana continues to shift toward community-based, rather than institutional, long-term services and supports (LTSS).23 In FY 2014, Louisiana’s Medicaid program spent $2.2 billion on LTSS, devoting approximately 39%, or $865 million, to home and community-based services (HCBS).24 The share of Medicaid LTSS dollars that have been devoted to HCBS increased from 37% in FY 2009 to 39% in FY 2014, which mirrors a national shift toward serving more people in home and community-based settings rather than institutions. This “rebalancing” of Medicaid LTSS expenditures is due in large part to beneficiary preferences for HCBS, the lower cost of HCBS relative to comparable institutional care, and states’ community integration obligations under the Supreme Court’s Olmstead decision.25

Health Coverage in Louisiana

In 2014, Louisiana had the one of the highest uninsured rates (13%) in the U.S. Half (50%) of Louisianans were covered under private health insurance, with 45% of Louisianans covered by employer-sponsored insurance and the remaining 5% covered by individual26 coverage (Figure 7). Over one quarter (26%) were covered by Medicaid/other public coverage and 11% were covered by Medicare. Of the over half million beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare, nearly a third (30%) were enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans in 2015.27

Individuals who were uninsured in 2014 were primarily low-income, in working families, and White non-Hispanic. Because most elderly Louisianans are covered by Medicare, most uninsured are nonelderly (under age 65). The majority of nonelderly, uninsured Louisianans in 2014 had at least one full-time worker in their household (65%) and had income below 400% of the federal poverty level (FPL, 85%). Almost half (49%) of nonelderly, uninsured Louisianans identified as White, over one-third (37%) identified as Black, and 15% identified as Hispanic (Figure 8). Additionally, Figure 16 (Appendix) shows how the uninsured rate varies across parishes in Louisiana.

Affordable Care Act Implementation and Coverage Changes

A main goal of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was to increase coverage of the uninsured population, including many of the 645,000 Louisianans who were uninsured prior to ACA implementation. The ACA sought to accomplish this through insurance market reforms and by establishing new coverage pathways, including providing premium subsidies to most uninsured individuals with incomes up to 400% FPL to purchase coverage on the Health Insurance Marketplace and an expansion of Medicaid to cover nearly all nonelderly adults up to 138% FPL ($16,394 per year for an individual or $27,820 for a family of three in 2016). The Supreme Court decision on the ACA’s constitutionality effectively made the adult Medicaid expansion a state option.28

In Louisiana, coverage through the Health Insurance Marketplace went into effect in January 2014, and the Medicaid expansion will be implemented in July 2016. When the ACA provisions went into effect in January 2014, Louisiana did not elect to establish a state-based exchange or to implement the Medicaid expansion. On January 1, 2014, the federal government established a federal Health Insurance Marketplace. Louisiana’s new Governor, Governor John Bel Edwards, adopted the Medicaid expansion in January 2016, with coverage beginning July 1, 2016.

The uninsured rate in Louisiana has been relatively flat following implementation of the ACA. Compared to the rest of the nation, which saw a significant decline in the uninsured rate in 2014 and 2015, the uninsured rate for the nonelderly in Louisiana decreased slightly from 15% in 2013 to 12% in 2015 (Figure 9), but this change is not statistically significant. In Louisiana, many uninsured individuals fell into the “coverage gap” in 2014 and 2015, prior to the adoption of the Medicaid expansion. In addition, while enrollment in Marketplace coverage was slow to take hold, it has grown over time.29 With Louisiana’s implementation of the Medicaid expansion in 2016, it is likely that the state will see a significant drop in the uninsured rate as people enroll in this new coverage option.

As part of the ACA, all states are required to implement new, simplified eligibility and enrollment processes, and Louisiana has made progress in implementing some of these changes. As of January 2016, individuals in Louisiana can apply for both Medicaid and Health Insurance Marketplace coverage through multiple pathways, including in-person, over the phone, by mail, and online.30 Simplified renewal process have been in place in Louisiana since prior to the ACA (Box 1).

Box 1: Louisiana’s Renewal Strategies Prior to the Affordable Care Act (ACA)

Prior to the ACA, Louisiana was recognized as a national leader for streamlining renewal processes for children receiving Medicaid and CHIP benefits. Relying heavily on data available from other sources to establish continued eligibility, the state’s renewal processes have been championed nationally. Over nine in ten (95%) children had their Medicaid or CHIP coverage renewed, and fewer than 1% lost coverage due to procedural reasons in 2008, in advance of the state’s use of Express Lane Eligibility (ELE).31 According to a 2014 report for the U.S. Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE), over three-quarters (76%) of children’s completed renewals were based on data matches.32,33 Other renewal strategies Louisiana has employed include 12 months continuous eligibility, rolling or “off cycle” renewals, electronic case files and signatures, and the use of a reasonable certainty standard when determining eligibility.34

The Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2009 (CHIPRA) established “Performance Bonuses” for states to support the enrollment and retention of eligible children in Medicaid. The Performance Bonuses provided additional federal funding for qualifying states that took steps to simplify Medicaid and CHIP enrollment and renewal procedures and increased Medicaid enrollment of children above a baseline level. Louisiana won CHIPRA Performance Bonus Awards for three consecutive years (FYs 2009, 2010, and 2011) due in part to their work in renewals.35

Health Insurance Marketplace

Louisianans are able to shop for health plans through HealthCare.gov, the federal Health Insurance Marketplace. Louisiana is one of 34 states in which the federal government established and is running the Health Insurance Marketplace.36 Monthly premiums for a benchmark Qualified Health Plan (QHP) in New Orleans before tax credits are $332 for an individual in 2016, an increase of 12% from 2015.37 In 2015, five carriers offered individual coverage in the Marketplace. Louisiana Health Cooperative stopped offering coverage in 2016, and, as a result, 16,000 enrollees had to find a new plan in 2016.38

Figure 10: Number of Individuals Selecting a Marketplace Plan, as a Share of the Potential Marketplace Population in Southern States, as of February 2016

On February 1, 2016, at the end of the Marketplace’s third open enrollment period, 214,000 Louisianans had selected a Marketplace plan, almost nine in ten (89%) of whom were eligible for premium subsidies to purchase coverage. Over one third (37%) of Marketplace enrollees in Louisiana were under age 35. Almost half (48%) of Louisianans enrolled in Marketplace coverage were new customers.39 Among all states, Louisiana had the 22nd largest share of the potential Marketplace population enrolled in a Marketplace plan as of February 2016 (45%) and the seventh largest share in the South (Figure 10).40

Support for outreach and enrollment in Louisiana is being provided by the federal government and private organizations. In 2015, two organizations received $1.561 million in federal navigator grant funds to provide enrollment assistance to Louisianans (Table 3). One of these two organizations, Southwest Louisiana Area Health Education Center operates statewide and has been awarded grants for all three open enrollment periods. Since 2013, federal funding for consumer assistance in Louisiana has decreased by over $200,000 and the number of organizations providing such services decreased from four to two.

| Table 3: Navigator Grant Recipients, their Funding Levels, and Percent of Total Grants Distributed, 2013-2015 | |||

| Organization | 2013 Funding | 2014 Funding | 2015 Funding |

| Total Funding Level | $1,767,174 | $1,133,256 | $1,560,723 |

| Capital Area Agency on Aging, District II, Inc. | $100,000 | $110,000 | — |

| Family Road of Greater Baton Rouge | — | — | $513,189 |

| Martin Luther King Health Center, Inc. | $81,066 | — | — |

| National Healthy Start Association | — | $391,846 | — |

| Southern United Neighborhoods | $486,123 | — | — |

| Southwest Louisiana Area Health Education Center | $1,099,985 | $1,023,256 | $1,047,534 |

| NOTE: “–“denotes that that organization was not a Navigator grant recipient in that year. | |||

| Source: Center for Consumer Information and Insurance Oversight, 2013, 2014, and 2015 Navigator Grant Recipients, https://www.cms.gov/cciio/programs-and-initiatives/health-insurance-marketplaces/assistance.html | |||

Medicaid in Louisiana After the ACA

Louisiana is the 32nd state (including DC) in the nation and the 7th of the 17 states that make up the American South to adopt the ACA Medicaid expansion. While most states implemented the Medicaid expansion on January 1, 2014, Louisiana did not expand under Governor Bobby Jindal. The newly elected Governor, John Bel Edwards, campaigned on implementing the Medicaid expansion and signed an executive order on January 12, 2016, his second day in office, adopting the Medicaid expansion.41 Unlike its neighbor Arkansas, Louisiana is implementing the Medicaid expansion using a State Plan Amendment (SPA), rather than a waiver; the SPA was approved by HHS in April 2016.42 Enrollment under the expansion began June 1, 2016, and coverage is scheduled to go into effect July 1, 2016.43 Through the Medicaid expansion, the state anticipates enrolling over 300,00044 Louisianans by using coordinated outreach and enrollment efforts and innovative, data-driven approaches to accelerate enrollment. Louisiana is the first state to obtain a state plan amendment to use Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) data to facilitate enrollment of eligible individuals into Medicaid (other states have received approval to use SNAP data to facilitate Medicaid enrollment through waiver authority).45 Louisiana also plans to target specific populations for outreach and enrollment, for example, by connecting individuals to Medicaid upon reentry into the community following release from incarceration.

In April 2016, Governor Edwards testified before Louisiana’s Senate Health and Welfare Committee stating that the expansion would result in state general fund savings. Additionally, estimates from the Louisiana Department of Hospitals and Health (DHH) in 2013 and the Louisiana Legislative Fiscal Office (LFO) in 2015 show net savings, with more saving when the state will receive a 100% match for dollars spent on individuals who are newly eligible.

Figure 11: Medicaid/CHIP Income Eligibility Thresholds Pre- and Post- Medicaid Expansion Adoption In Louisiana

Eligibility levels for parents and childless adults will increase after implementation of the Medicaid expansion (Figure 11). When the coverage expansion takes effect on July 1, 2016, Louisiana’s parent eligibility threshold will increase from 24% ($4,838 for a family of three in 2016) FPL to 138% FPL ($27,820 for a family of three in 2016). Childless adults will be newly eligible for coverage with incomes up to 138% FPL ($16,394 for an individual in 2016).46 Eligibility levels for children and pregnant women through Medicaid and CHIP will remain higher at 255% FPL ($51,408 for a family of three in 2016) and 214% FPL ($43,142 for a family of three in 2016), respectively.

As a result of the adoption of the Medicaid expansion, a third of the uninsured population moved from falling into a “coverage gap” to being eligible for coverage. Before the state expanded Medicaid, a third of the nonelderly uninsured population fell into a “coverage gap” because they were childless adults or earned too much to qualify for Medicaid but not enough to qualify for Marketplace tax credits. After the adoption of the Medicaid expansion, over half (53%) of nonelderly uninsured people in the state are eligible for Medicaid or CHIP. Additionally, one in five (20%) is eligible for premium tax credits to help purchase private coverage in the Marketplace.47

Most Medicaid beneficiaries are currently enrolled in managed care plans. In Louisiana, 71% of the total Medicaid population are enrolled in one of the state’s nine managed care plans (Figure 12).48 However, the penetration rate varies across eligibility groups. Almost all (99%) of children are enrolled in a Medicaid managed care plan whereas only about one-third (37%) of low-income adults and two-fifths (40%) of seniors and people with disabilities are enrolled in Medicaid managed care plans. All of the nine Medicaid managed care plans are owned by a multi-state parent firm.49 As of December 2015, Louisiana had integrated all specialized behavioral health care services into the state’s Medicaid managed care program.50

Safety Net in Louisiana

In Louisiana, health care for the indigent is a state, rather than local, responsibility. The state, through its safety net hospitals, provides care free of charge for state residents with incomes at or below 200% FPL. For uninsured individuals above 200% FPL, charges are reduced by 40%.51 While the hospitals provide low-income, uninsured individuals with a broad array of medical services, the system’s focus is acute care and provides fewer options for primary care.52,53

Prior to 2012, Louisiana essentially had a “two-tier” health system. The insured population (including those with Medicare and Medicaid) had access to a range of community hospitals and physicians, while the poor and uninsured were mostly cared for through the Louisiana State University (LSU)-run system of 10 state-funded inpatient hospitals (including New Orleans Charity Hospital before Hurricane Katrina) and a network of more than 350 clinics. Eight of the ten state hospitals fell under the administrative responsibility of the LSU Health Care Services Division (LSUHCSD) and two were operated by LSU Health Sciences Center in Shreveport.54

The health system providing care to the uninsured in Louisiana was largely driven by financing mechanisms. Medicaid represented not only a system of health care coverage for low-income people in Louisiana but also a mechanism of financing health care for the uninsured. Louisiana was a major user of Medicaid DSH funding; in FY 2014, Louisiana’s $1.1 billion in DSH funds accounted for over 15% of all Medicaid spending in the state (compared with about under 4% nationwide).55 DSH payments are made by a state’s Medicaid program to hospitals that the state designates as serving a “disproportionate share” of low-income or uninsured patients. These payments are in addition to the regular payments such hospitals receive for providing inpatient care to Medicaid beneficiaries. In Louisiana, the state allocated most of its Medicaid DSH payments to the LSU system to finance care for the uninsured. While the LSU system offered outpatient and ambulatory care services, Louisiana’s use of Medicaid DSH funds in this way created a reliance on inpatient hospital care for the poor.56

Prior to Hurricane Katrina in 2005, Charity Hospital and University Hospital were hubs of the LSU system in New Orleans, serving a largely poor, predominantly minority population through inpatient care clinics, a network of outpatient clinics, and one of the busiest emergency departments (EDs) in the country. Nearly three-quarters of Charity Hospital’s patients were African American, and 85% had annual individual incomes of less than $20,000.57 In 2003 more than half of the inpatient care provided by Charity Hospital was for patients without insurance, compared with only 4% of inpatient care at other New Orleans hospitals.58 It was also the dominant provider of substance abuse, psychiatric, and HIV/AIDS care in the New Orleans area and the only Level 1 trauma center on the Gulf Coast.

Hurricane Katrina devastated the New Orleans health care safety net, closing Charity Hospital, University Hospital, and most of the city’s other hospitals. Both of these hospitals were eventually replaced by University Medical Center New Orleans (UMCNO) in August 2015, which is now the city’s main trauma and safety-net hospital.59 UMCNO cost $1.1 billion to construct, most of which was provided by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).60

In summer 2012, the Louisiana Legislature reduced Medicaid funding, applying the majority of the cuts to the public hospital system.61 In late 2012 and early 2013, the LSU hospitals were leased to private companies, creating private-public partnerships to operate the hospitals. In the partnerships, the private companies lease and operate the hospital and its affiliated clinics. Of the ten original charity hospitals, five62 were transitioned to the private partners during FY 2013 and another four63 were transitioned during FY 2014.64 Only one hospital, Lallie Kemp Regional Medical Center in Independence, Louisiana, is still operated by the state.65 The privately run hospitals are required to continue to provide indigent care to uninsured individuals with incomes up to 200% FPL, graduate medical education, and care to public offenders.66 While contracts with the hospitals state that the hospitals must continue to provide these services, it is currently unclear how the privatization has impacted access to care for the uninsured. Additionally, as of 2014, Our Lady of the Lake’s hospital agreement allowed the hospital to discontinue providing care to public offenders.67

Box 2: Impact of Hurricane Katrina on Primary Care in New Orleans

Before Hurricane Katrina, the delivery system was hospital dominated. With the destruction of this system in 2005, efforts to broaden community based primary care have increased. After Hurricane Katrina in 2005, the state received $100 million for a federal Primary Care Access Stabilization Grant (PCASG) through September 2010 to increase coverage for low-income populations in New Orleans. This funding restored and expanded access to primary care services, including mental health and dental care. To maintain funding after the grant ended, the state received approval for a Section 1115 waiver in September 2010 called the Greater New Orleans Community Health Connection (GNOCHC) Program.

The current waiver (extended in 2014) provides limited benefit coverage (primary and preventive care, behavioral health, some specialty care and care coordination68) for uninsured, nonelderly adults with incomes up to and including 100% FPL living in or around the city of New Orleans (Orleans, Jefferson, St. Bernard, or Plaquemines parishes) and not currently eligible for other public coverage. Under the waiver, the state can implement an enrollment cap to control costs. Care is provided by those providers that participated in the PCASG program that preceded the GNOCHC waiver. The most recent renewal also removes Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment (EPSDT) for individuals ages 19 and 20, retroactive eligibility, and non-emergency medical transportation.69,70

Figure 13: Selected Characteristics of Patients Served by Federally Qualified Health Centers in Louisiana, 2014

Louisiana’s safety net providers play an important role in delivering health care to the state’s most vulnerable populations. Louisiana’s community health centers provide access to primary and preventive services for low-income and underserved residents. Louisiana is home to 30 federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), which operate 162 sites throughout the state. In 2014, the state’s FQHCs saw over 303,000 patients and provided nearly 1.1 million patient visits. Over a third (37%) of their patients were uninsured and two-fifths (40%) had Medicaid coverage (Figure 13). Nearly all (93%) had incomes below 200% FPL, including over three-quarters (77%) who had income below 100% FPL.71

There is unmet need for health care providers in Louisiana. As of April 2014, Louisiana had 118 primary care Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSA), 102 dental HPSAs, and 109 mental health HPSAs. In primary care and dental care providers per population, Louisiana fared better than the U.S. overall in percent of need met to adequately serve the population. Seventy-eight percent of the primary health care provider need and 62% of dental care provider need in Louisiana was met, compared to 60% for primary care and 41% for dental care nationally (Figure 14). However, Louisiana has less than half (42%) of the number of mental health care providers needed to adequately serve the population, compared to just over half (51%) for the nation as a whole.72

Figure 14: Percent of Primary Care, Dental Care, and Mental Health Care Practitioner Capacity Need Met, April 2014

As of 2014, Louisiana ranked 10th in the country for the ratio of medical students to 100,000 population (45.3 in Louisiana compared to 30.4 nationally). However, Louisiana ranked 20th among states in the percentage of physicians completing graduate medical education in the state who remain in-state to practice (47%).73 Louisiana is one of 17 states with licensure laws that limit the autonomy of nurse practitioners in at least one area of practice.74

Looking Ahead

With 4.5 million residents, health coverage and care decisions Louisiana will continue to have important implications for the health and well-being of the state’s most vulnerable populations and the national healthcare landscape. With Louisiana being the most recent state to adopt the Medicaid expansion, the coverage gap is eliminated for the uninsured adults below poverty and a continuum of care coverage will be available for all uninsured Louisianans. Outreach and enrollment efforts will be important to connect the newly insured to coverage. Meanwhile, the health care system in Louisiana is evolving and changing to meet new demands as providers adapt to the changing health coverage landscape.

Appendix

Endnotes

The Kaiser Family Foundation’s State Health Facts. Data Source: Kaiser Family Foundation estimates based on the Census Bureau's March 2015 Current Population Survey (CPS: Annual Social and Economic Supplement). Accessed February 10, 2016. “Total Number of Residents,” https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/total-residents/.

World Atlas, Louisiana, http://www.worldatlas.com/webimage/countrys/namerica/usstates/paland.htm.

US Census Bureau, 2010-2014 American Community Survey, County Total Population Estimates.

Kaiser Family Foundation estimates based on the Census Bureau's March 2015 Current Population Survey (CPS: Annual Social and Economic Supplement).

Kaiser Family Foundation estimates based on the Census Bureau's March 2015 Current Population Survey (CPS: Annual Social and Economic Supplements).

United Health Care Foundation, America’s Health Rankings (2015), http://www.americashealthrankings.org/.

The Commonwealth Fund. Aiming Higher: Scorecard on State Health System Performance, 2014, http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2014/apr/2014-state-scorecard.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Health Statistics, Division of Vital Statistics, National Vital Statistics Reports (NVSR) Volume 64, Number 2, Table 19, http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr64/nvsr64_02.pdf.

K. Kost and S. Henshaw. “U.S. Teenage Pregnancies, Births and Abortions, 2010: National and State Trends by Age, Race and Ethnicity. Table 3.3.” http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/USTPtrends10.pdf.

United States Cancer Statistics (USUC), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2012 Selected Cancers Ranked by State, https://nccd.cdc.gov/USCS/cancersrankedbystate.aspx#text.

Rose Rudd, Noah Aleshire, Jon Zibbell, and R. Matthew Gladden, Increases in Drug and Opioid Overdose Deaths – United States, 2000-2014 (Atlanta, Louisiana: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, January 1, 2016), http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6450a3.htm.

Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals, Bureau of Minority Health Access & Promotions, http://new.dhh.louisiana.gov/index.cfm/page/269/n/171.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health, Louisiana State Partnership Grant to Address Health Disparities Program (LPAHD), http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/content.aspx?lvl=2&lvlid=66&ID=126.

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Current-Dollar GDP by State, Louisiana, 2014 (December 10, 2015).

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Current-Dollar GDP by State, Louisiana, 2014 (December 10, 2015).

Louisiana and state figures from Table 3, Civilian Labor Force and Unemployment by State and Selected Area, Seasonally Adjusted (April 14, 2016), http://www.bls.gov/news.release/laus.t03.htm. U.S. figure from Bureau of Labor Statistics, Unemployment Rate (Seasonally Adjusted) (February 17, 2016), http://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/surveymost?bls.

Lucy Dadayan and Donald Boyd, Double, Double, Oil and Trouble. The Nelson A. Rockefeller Institute of Government, February 2016. http://www.rockinst.org/pdf/government_finance/2016-02-By_Numbers_Brief_No5.pdf.

Governor Edwards Announces Solutions to Stabilize Louisiana Budget, Office of the Governor, January 19, 2016, http://gov.louisiana.gov/news/gov-edwards-announces-initial-solutions-to-fy16-and-fy17-budget-shortfalls.

Edwards Issues Statement on Revenue Estimating Conference Meeting, Office of the Governor, March 16, 2016, http://gov.louisiana.gov/news/edwards-issues-statement-on-revenue-estimating-conference-meeting.

House Bill 1, Louisiana State Legislature, http://legis.la.gov/legis/BillInfo.aspx?s=16RS&b=HB1&sbi=y.

Urban Institute analysis of CMS Form 64 data as of June 2015, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/federalstate-share-of-spending/.

80 Fed. Reg. 73779-73782. (November 25, 2015), at https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2015-11-25/pdf/2015-30050.pdf.

Steve Eiken, Kate Sredl, Brian Burwell, Paul Saucier, Medicaid Expenditures for Long-Term Services and Supports (LTSS) in FY 2013: Home and Community-Based Services were a Majority of LTSS Spending, (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and Truven Health Analytics, June 308, 2015), https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid-chip-program-information/by-topics/long-term-services-and-supports/downloads/ltss-expenditures-fy2013.pdf.

Steve Eiken, Kate Sredl, Brian Burwell, and Paul Saucier, Medicaid Expenditures for Long-Term Services and Supports (LTSS) in FY 2014: Managed LTSS Reached 15 Percent of LTSS Spending (Bethesda, MD: Truven Health Analytics, April 2015), https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid-chip-program-information/by-topics/long-term-services-and-supports/downloads/ltss-expenditures-2014.pdf.

The Olmstead decision found that the unjustified institutionalization of persons with disabilities violates the Americans with Disabilities Act. Olmstead v. L.C. 527 U.S. 581 (1999), http://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/98-536.ZS.html.

Includes individuals and families that purchased or are covered as a dependent by non-group insurance.

State Health Facts. “Medicare Advantage Enrollment as a Percent of Total Medicare Population” (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2015), https://www.kff.org/medicare/state-indicator/enrollees-as-a-of-total-medicare-population/.

MaryBeth Musumeci, A Guide to the Supreme Court’s Affordable Care Act Decision (Washington, D.C.: Kaiser Family Foundation, June 2012), https://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/a-guide-to-the-supreme-courts-affordable/.

Health Insurance Marketplaces 2016 Open Enrollment Period: Final Enrollment Report for the period: November 1, 2015 - February 1, 2016, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), March 11, 2016, https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/187866/Finalenrollment2016.pdf.

Addendum to the Health Insurance Marketplaces 2016 Open Enrollment Period: Final Enrollment Report for the period: November 1, 2015 - February 1, 2016, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), March 11, 2016, https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/188026/MarketPlaceAddendumFinal2016.pdf.

Tricia Brooks, Sean Miskell, Samantha Artiga, Elizabeth Cornachione, and Alexandra Gates, Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility, Enrollment, Renewal, and Cost-Sharing Policies as of January 2016: Findings from a 50-State Survey (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation’s Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, January 2016), https://www.kff.org/medicaid/report/medicaid-and-chip-eligibility-enrollment-renewal-and-cost-sharing-policies-as-of-january-2016-findings-from-a-50-state-survey/

Tricia Brooks, The Louisiana Experience: Successful Steps to Improve Retention in Medicaid and SCHIP (Washington, D.C.: Georgetown Center for Children and Families, February 2009) http://ccf.georgetown.edu/ccf-resources/louisiana-experience-successful-steps-improve-retention-medicaid-schip/

Administrative renewal is conducted for children whose families have a financial situation that makes continued eligibility almost certain, and ex-parte renewal is when caseworkers determine a child’s eligibility with reasonable certainty by investigating multiple data sources, including SNAP, TANF, and wage/unemployment insurance information, etc.

Stan Dorn, Sarah Minton, Erika Huber, Examples of Promising Practices for Integrating and Coordinating Eligibility, Enrollment and Retention: Human Services and Health Programs Under the Affordable Care Act (Washington, D.C.: The Urban Institute, July 21, 2014), https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/examples-promising-practices-integrating-and-coordinating-eligibility-enrollment-and-retention-human-services-and-health-programs-under-affordable-care-act.

Stan Dorn, Sarah Minton, Erika Huber, Examples of Promising Practices for Integrating and Coordinating Eligibility, Enrollment and Retention: Human Services and Health Programs Under the Affordable Care Act (Washington, D.C.: The Urban Institute, July 21, 2014), https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/examples-promising-practices-integrating-and-coordinating-eligibility-enrollment-and-retention-human-services-and-health-programs-under-affordable-care-act.

State Health Facts. “CHIPRA Performance Bonus Awards” (Washington, D.C.: Kaiser Family Foundation, FY 2009-2013), https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/chipra-performance-bonuses/.

State Health Facts. “State Decisions for Creating Health Insurance Marketplaces” (Kaiser Family Foundation, February 19, 2015), http://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/health-insurance-exchanges/.

State Health Facts, “Monthly Silver Premiums for a 40 Year Old Non-Smoker Making $30,000/Year” (Washington, D.C.: Kaiser Family Foundation, 2015-2016), https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/monthly-silver-premiums-for-a-40-year-old-non-smoker-making-30000year/.

State Health Facts. “Number of Issuers Participating in the Individual Health Insurance Marketplaces” (Washington, D.C.: Kaiser Family Foundation, 2014 – 2016), https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/number-of-issuers-participating-in-the-individual-health-insurance-marketplace/.

According to ASPE’s January 2016 Enrollment Report: “New Consumers” are those individuals who selected a 2016 Marketplace medical plan (with or without the first premium payment having been received directly by the issuer) as of the reporting date, and did not have a Marketplace plan selection as of November 2015.

Health Insurance Marketplaces 2016 Open Enrollment Period: Final Enrollment Report for the period: November 1, 2015 - February 1, 2016, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), March 11, 2016, https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/187866/Finalenrollment2016.pdf.

Addendum to the Health Insurance Marketplaces 2016 Open Enrollment Period: Final Enrollment Report for the period: November 1, 2015 - February 1, 2016, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), March 11, 2016, https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/188026/MarketPlaceAddendumFinal2016.pdf.

Louisiana Office of the Governor, Edwards Signs Executive Order to Provide Health Care for Working Families, January 12, 2016, http://gov.louisiana.gov/news/edwards-signs-executive-order-to-provide-health-care-for-working-families.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Louisiana State Plan Amendment to Expand Medicaid, https://www.medicaid.gov/State-resource-center/Medicaid-State-Plan-Amendments/Downloads/LA/2016/LA-16-0004.pdf.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Louisiana State Plan Amendment to Expand Medicaid, https://www.medicaid.gov/State-resource-center/Medicaid-State-Plan-Amendments/Downloads/LA/2016/LA-16-0004.pdf.

“Governor Edwards: Enrollment for Medicaid Expansion to Begin on June 1,” Louisiana State Website, April 18, 2016 http://gov.louisiana.gov/news/enrollment-for-medicaid-expansion-to-begin-on-june-1 and presentation by Rebekah Gee, MD, DHH Secretary, May 9, 2016.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Press Release, “HHS Secretary Sylvia M. Burwell Applauds Louisiana Medicaid Expansion Under the Affordable Care Act,” http://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2016/05/31/hhs-secretary-sylvia-m-burwell-applauds-louisiana-medicaid-expansion-under-affordable-care-act.html

Tricia Brooks, Sean Miskell, Samantha Artiga, Elizabeth Cornachione, and Alexandra Gates, Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility, Enrollment, Renewal, and Cost-Sharing Policies as of January 2016: Findings from a 50-State Survey (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation’s Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, January 2016), https://www.kff.org/medicaid/report/medicaid-and-chip-eligibility-enrollment-renewal-and-cost-sharing-policies-as-of-january-2016-findings-from-a-50-state-survey/.

Rachel Garfield, Anthony Damico, Cynthia Cox, Gary Claxton, and Larry Levitt, New Estimates of Eligibility for ACA Coverage among the Uninsured, (Washington, D.C.: Kaiser Family Foundation, January 2016), http://files.kff.org/attachment/data-note-new-estimates-of-eligibility-for-aca-coverage-among-the-uninsured.

State Health Facts. “Medicaid Managed Care Penetration Rates by Eligibility Group” (Washington, D.C.: Kaiser Family Foundation, July 1, 2015), https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/managed-care-penetration-rates-by-eligibility-group/.

State Health Facts. “Medicaid MCOs and their Parent Firms” (Washington, D.C.: Kaiser Family Foundation, March 2015), https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/medicaid-mcos-and-their-parent-firms/.

Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals, DHH Announces Plans to Integrate Behavioral Health Services into Medicaid Managed Care Plans, November 19, 2014, http://dhh.louisiana.gov/index.cfm/newsroom/detail/3165.

LUS Policy 2525-12 Charity Care, http://www.lsu.edu/bos/hospital-ceas/umcmc/docs/LSU-Policy-2525-12-Charity-Care-3.pdf.

Don Gregory and Alison Neustrom, “A New Safety Net: The Risk and Reward of Louisiana’s Charity Hospital Privatization” (Baton Rouge, LA: Public Affairs Research Council of Louisiana, 2013), http://www.parlouisiana.org/s3web/1002087/docs/parhospital2013.pdf.

It is unclear whether the indigent care system will be affected by the adoption of the Medicaid expansion, but should lead to a reduction in the uninsured and would mean more coverage options for those currently uninsured and using these programs.

Robin Rudowitz, Diane Rowland and Adele Shartzer, Health Care In New Orleans Before And After Hurricane Katrina, Health Affairs 25, no.5 (2006):w393-w406, doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.w393 originally published online August 29, 2006, http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/25/5/w393.full?keytype=ref&siteid=healthaff&ijkey=NVgQvGWGxvVqA.

State Health Facts. “Distribution of Medicaid Spending by Service” (Washington, D.C.: Kaiser Family Foundation, May 4, 2016), https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/distribution-of-medicaid-spending-by-service/.

Stephen Zuckerman and Teresa Coughlin, Initial Health Policy Reponses to Hurricane Katrina and Possible Next Steps (Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute, February 2006), http://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/alfresco/publication-pdfs/900929-Initial-Health-Policy-Responses-to-Hurricane-Katrina-and-Possible-Next-Steps.PDF.

Robin Rudowitz, Diane Rowland and Adele Shartzer, Health Care In New Orleans Before And After Hurricane Katrina, Health Affairs 25, no.5 (2006):w393-w406, doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.w393 originally published online August 29, 2006, http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/25/5/w393.full?keytype=ref&siteid=healthaff&ijkey=NVgQvGWGxvVqA.

Uncompensated care cost data for 2003 provided to the authors of the Health Affairs article by the Louisiana Hospital Association.

University Hospital was reopened in 2006 under the name LSU Interim Hospital. This hospital was then closed and moved all of its patients to University Medical Center New Orleans in August 2015.

University Medical Center New Orleans, “About Us,” http://www.umcno.org/aboutumc.

“Louisiana Cuts Medicaid Program to the Bone,” The Times-Picayune (New Orleans, Louisiana), July 13, 2012, http://www.nola.com/politics/index.ssf/2012/07/louisiana_cuts_medicaid_progra.html.

The five hospitals privatized in FY 2013 were: Earl K. Long Medical Center in Baton Rouge (now closed, services moved to Our Lady of the Lake Hospital); Interim LSU Public Hospital in New Orleans (now University Medical Center New Orleans); University Medical Center in Lafayette (now Lafayette General Medical Center); Leonard J. Chabert Medical Center in Houma (now Ochsner Leonard J. Chabert Medical Center); and W.O. Moss Regional Medical Center in Lake Charles (now Moss Memorial Health Clinic).

The four hospitals privatized in FY 2014 were: LSU Medical Center in Shreveport (now University Health Shreveport); E. A. Conway Medical Center in Monroe (now University Health Conway); Huey P. Long Medical Center in Pineville (now closed, services moved to a new campus that offers an Urgent Care Clinic, Medicine Clinic, Specialty Clinic, and Pharmacy Services); and Bogalusa Medical Center (Our Lady of the Angels Hospital).

Don Gregory and Alison Neustrom, “A New Safety Net: The Risk and Reward of Louisiana’s Charity Hospital Privatization” (Baton Rouge, LA: Public Affairs Research Council of Louisiana, 2013), http://www.parlouisiana.org/s3web/1002087/docs/parhospital2013.pdf.

Don Gregory and Alison Neustrom, “A New Safety Net: The Risk and Reward of Louisiana’s Charity Hospital Privatization” (Baton Rouge, LA: Public Affairs Research Council of Louisiana, 2013), http://www.parlouisiana.org/s3web/1002087/docs/parhospital2013.pdf.

Hospital Cooperative Endeavor Agreements, LSU Board of Supervisors, http://www.lsu.edu/bos/hospital-ceas.php.

Cooperative Endeavor Agreement by and Among Our Lady of the Lake Hospital, Inc. and Board of Supervisors of LSU and Agricultural and Mechanical College, The State of Louisiana through the Division of Administration, and the Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals, http://www.lsu.edu/bos/hospital-ceas/ololbr/docs/CEA.pdf.

The waivers benefit package offers care coordination, immunizations/flu vaccines, laboratory and radiology, mental health, primary care, preventive care, substance abuse services, and specialty care (when referred from a primary care provider).

Greater New Orleans Community Health Connection (GNOCHC) Waiver Approval, November 25, 2014, https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/la/la-gnoch-ca.pdf.

It is unclear whether the Section 1115 waiver will be affected by the adoption of the Medicaid expansion, but should lead to a reduction in the uninsured and would mean more coverage options for those currently uninsured and using these programs.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources & Services Administration (HRSA) Health Center Program, 2014 Health Center Data, Louisiana Program Grantee Data, http://bphc.hrsa.gov/uds/datacenter.aspx?year=2014&state=LA.

Bureau of Clinician Recruitment and Service, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, HRSA Data Warehouse: Designated Health Professional Shortage Areas Statistics, as of April 28, 2014, https://datawarehouse.hrsa.gov/Tools/HDWReports/Reports.aspx.

Association of American Medical Colleges, Louisiana Physician Workforce Profile 2014, https://www.aamc.org/download/447182/data/louisianaprofile.pdf.

American Association of Nurse Practitioners, State Practice Environment 2015, https://www.aanp.org/images/documents/state-leg-reg/stateregulatorymap.pdf.