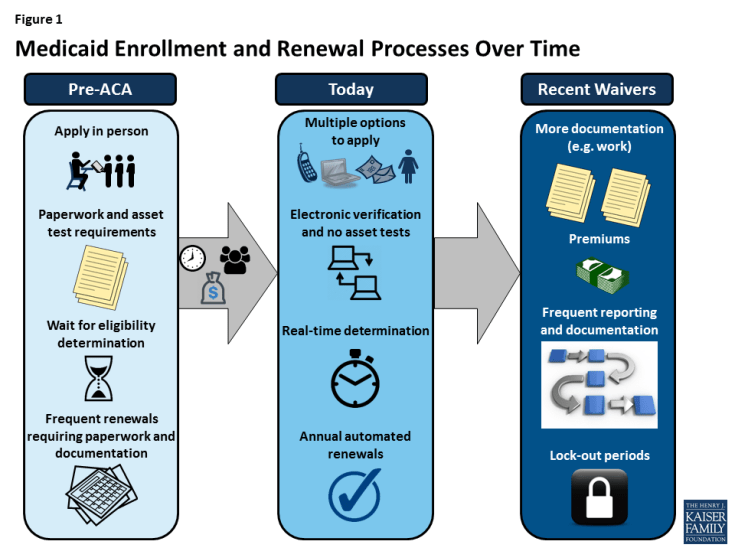

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) significantly modernized and streamlined Medicaid enrollment and renewal processes across all states. Through major investments of time, money, and staff, most states have implemented modernized systems that transformed lengthy, paperwork driven enrollment and renewal procedures to a simplified, technology-driven experience that minimizes burdens on individuals and states. Recently approved and proposed waivers and other proposed policies include new eligibility and enrollment requirements and restrictions that run counter to the ACA’s streamlined processes (Figure 1). This fact sheet provides an overview of how enrollment and renewal processes changed under the ACA and the implications of emerging waivers and other proposed changes on streamlined enrollment and renewal.

Enrollment and Renewal Before the ACA

Historically, enrolling in Medicaid was a burdensome process similar to applying for cash welfare. A person often had to take time off work to apply in person at a welfare office, provide substantial paper documentation of income and other eligibility criteria, and wait weeks or in some cases months for an eligibility determination. Moreover, individuals often would have to repeat these steps at renewal, which could occur every six months. Many aspects of the historical enrollment process reflected the Medicaid program’s original ties to cash welfare and goals of curbing enrollment in Medicaid and welfare. One of the most significant barriers to Medicaid enrollment was difficulty completing the application process, including problems obtaining documentation and the overall hassle and complexity of the process.1 Given this and other barriers, many individuals who were eligible for Medicaid remained uninsured.

Spurred by CHIP and its goal of reducing the number of uninsured children, states began to streamline enrollment and renewal procedures to connect eligible people to coverage and keep them enrolled. Medicaid was delinked from welfare when Temporary Assistance for Needy Families was enacted in 1996. Building on Medicaid coverage for children, CHIP was implemented in 1997. As Medicaid and CHIP developed as health coverage programs separate from welfare with goals of enrolling and retaining eligible people in coverage, some states streamlined enrollment and renewal processes by eliminating in-person interviews, coordinating program rules between Medicaid and CHIP, offering multiple enrollment methods, reducing documentation requirements, and reducing the frequency of renewal.2 These actions contributed to increased enrollment and retention.3 Conversely, previous state experience also showed that reinstatement of enrollment barriers leads to significant enrollment declines. For example, in 2003, Texas experienced a nearly 30% enrollment decline after it increased premiums, established a waiting period, and moved from a 12- to 6-month renewal period for children in CHIP.4 When Washington State increased documentation requirements, moved from a 12- to 6-month renewal period, and ended continuous eligibility for children in Medicaid and CHIP in 2003, there was a sharp drop off in enrollment.5 Enrollment quickly rebounded when it reinstated the 12-month renewal period and continuous eligibility.6 When states implemented new requirements to document citizenship in 2007, there was a large drop off in enrollment of U.S. citizen children who were unable to provide the required paperwork.7

Streamlining of Enrollment and Renewal Under the ACA

In addition to expanding Medicaid to low-income adults, the ACA transformed Medicaid enrollment and renewal processes for low-income adults and children across all states to provide a modernized, technology-driven experience. The streamlined processes established by the ACA (Box 1) built on previous state experience connecting eligible children to Medicaid and CHIP and supported the ACA’s goals of reducing the number of uninsured and keeping individuals covered over time. The new processes aimed to facilitate access to coverage and keep families connected to coverage using technology to provide a consumer friendly experience and minimize administrative burdens on states. The ACA also provided federal funding to support states in replacing or upgrading antiquated eligibility systems and establishing links to other data sources to implement the new processes.

| Box 1: Medicaid and CHIP Enrollment and Renewal Processes Established Under the ACA |

|

With significant investments of time, money, and staff, most states have largely realized the streamlined technology-driven enrollment and renewal processes outlined in the ACA. Today, in nearly every state, individuals can apply using the method that works best for them—online, by phone, in-person, or via mail. Moreover, in a growing number of states, an individual can receive a determination in real-time (less than 24 hours) without having to submit pay stubs or other documentation when the state is able to verify eligibility criteria through electronic data matches with trusted data sources. Most states are using electronic data matches to renew coverage without the individual having to submit paperwork.

The simplified modernized processes help connect eligible individuals to coverage, keep eligible individuals enrolled, reduce paperwork burdens for individuals and states, and lead to increased administrative efficiencies. The modernized systems also offer new program management options. For example, states may have increased data reporting capabilities, enhanced ability to maintain program integrity, and expanded options to connect Medicaid with other systems and programs, which may facilitate connecting individuals to services. As systems and processes become more refined over time, states may be able to manage enrollment more efficiently, allowing them to refocus resources on other activities.

Implications of Emerging Waivers and Proposed Policies

Recently approved and proposed waivers and other proposed policy changes are likely to create complex documentation and administrative processes that run counter to simplified enrollment and renewal. Recently approved and proposed Section 1115 waivers include new eligibility and enrollment restrictions and requirements, such as work requirements, premiums, time limits on coverage, drug screening and testing requirements, asset tests, more frequent redeterminations, and lockouts for failure to pay premiums or provide timely information about changes in circumstances or for renewal. The President’s FY2019 budget includes proposals to allow states once again to require individuals to meet an asset test and to provide documentation to verify immigration and citizenship status before enrolling in Medicaid, although, under current law, states already are required to verify immigration and citizenship status.

Increased eligibility restrictions and documentation requirements create barriers for eligible individuals to obtain and maintain coverage and increase administrative burdens and costs for states (Figure 2). Many of these new requirements would require individuals to submit documentation of information and, in some cases, to provide documentation on a frequent, including monthly, basis. For example, in Kentucky and Indiana, enrollees would have to document their work status or their exemption from new work requirements on an ongoing basis. Some eligible individuals could lose coverage due to challenges navigating these processes. For states, implementation would likely require increased involvement of eligibility workers to process cases, which would slow down determinations and create the potential for errors or misdirected paperwork that could result in eligible people being denied or losing coverage. States may also face increased administrative costs that would detract from projected savings from these initiatives. Kentucky estimates increased administrative costs to implement its new work requirement.8 States also could have costs associated with contracting out to private vendors to manage new processes.

Figure 2: Examples of Increased Administrative Requirements for States and Individuals Under Recent Waivers

Endnotes

Michael Perry, Susan Kannel, R. Burciaga Valdez, and Christina Chang, Medicaid and Children, Overcoming Barriers to Enrollment, Findings from a National Survey, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, January 2000), https://www.kff.org/medicaid/report/medicaid-and-children-overcoming-barriers-to-enrollment/.

Kaiser Family Foundation, Key Lessons from Medicaid and CHIP for Outreach and Enrollment Under the Affordable Care Act, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, June 4, 2013), https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/key-lessons-from-medicaid-and-chip-for-outreach-and-enrollment-under-the-affordable-care-act/.

Ibid.

Ibid

Donna Cohen Ross and Laura Cox, Beneath the Surface: Barriers Threaten to Slow Progress on Expanding Health Coverage of Children and Families, A 50 State Update on Eligibility, Enrollment, Renewal, and Cost-Sharing Practices in Medicaid and CHIP, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, October 2004), https://www.kff.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/beneath-the-surface-barriers-threaten-to-slow-progress-on-expanding-health-coverage-of-children-and-families-pdf.pdf and Laura Summer and Cindy Mann, Instability of Public Health Insurance Coverage for Children and their Families: Causes, Consequences, and Remedies, (New York: The Commonwealth Fund, June 2006), http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2006/jun/instability-of-public-health-insurance-coverage-for-children-and-their-families--causes--consequence.

Laura Summer and Cindy Mann, op cit.

Kaiser Family Foundation, New Requirements for Citizenship Documentation in Medicaid, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, December 18, 2007), https://www.kff.org/medicaid/fact-sheet/new-requirements-for-citizenship-documentation-in-medicaid/.

Deborah Yetter, “Bevin’s Medicaid changes actually mean Kentucky will pay more to provide health care,” Louisville Courier Journal, February 14, 2018, https://www.courier-journal.com/story/news/politics/2018/02/14/kentucky-medicaid-changes-bevin-work-requriements/319384002/