Medicaid's Role for People with Dementia

Almost one-half (46%) of nursing facility residents1 and about one in five (21%) seniors living in the community has probable or possible dementia,2 a syndrome characterized by a chronic, progressive decline in memory and other cognitive functions, such as communication and judgment. People with dementia often have complex medical and behavioral health needs, and many rely on family caregivers to provide assistance with self-care and other daily activities.3,4 As dementia advances, paid care may be needed. Most people with dementia have Medicare,5 but due to high out-of-pocket costs and lack of long-term services and supports (LTSS) coverage, low-income people with disabilities resulting from dementia may need Medicaid to fill in the coverage gaps. Medicaid plays an important role in providing LTSS and is increasingly focused on efforts to help seniors and people with disabilities remain in the community rather than reside in institutions.

Given the expected growth of the elderly population over the coming decades6 and barring medical breakthroughs, a larger share of Americans likely will have dementia, which has implications for Medicaid coverage, delivery system design, financing, and quality monitoring. This fact sheet describes Medicaid’s role for people with dementia who live in the community, highlighting common eligibility pathways, beneficiary characteristics, covered services, health care spending and utilization, and key policy issues.

How do people with dementia qualify for Medicaid?

About a quarter (24%) of adults with dementia living in the community has Medicaid coverage over the course of a year.7 Nearly all adults with dementia (95%) receive Medicare benefits,8 and some also may qualify for Medicaid through an age (65+) or disability-related pathway if they have low income and limited assets. Medicaid financial eligibility criteria vary by state, subject to certain federal minimum requirements. 9,10 In most states, people who qualify for Supplemental Security Income (SSI) benefits are automatically eligible for Medicaid.11 To be eligible for SSI, beneficiaries must have low incomes (approximately 74% of poverty, or $8,796 per year for an individual) and limited assets and be unable to work. States also have the option to provide Medicaid coverage to seniors and people with disabilities with income up to 100 percent of the federal poverty level ($11,770 per year for an individual in 2015). In addition, states may opt to offer Medicaid coverage to people who have spent down excess income or assets to meet the financial eligibility threshold.12

People with dementia also may qualify for Medicaid through pathways targeted to people with LTSS needs. Some states extend Medicaid eligibility to people that require a certain level of care but have incomes above limits for other pathways. In addition to income and asset requirements, these pathways require that people meet certain functional eligibility criteria (e.g., need institutional level of care, determined by need for assistance with a certain number of activities of daily living such as bathing or eating and/or instrumental activities of daily living such as cooking or managing medications). These criteria vary across states and eligibility pathways.13 However, functional eligibility criteria may not always account for the full extent needs among people with dementia. For example, some functional needs assessments may only account for a need for hands-on assistance and may not recognize a need for verbal or written cues or monitoring to complete daily activities, which may be experienced by people with dementia. As a result, not all people with dementia are eligible for Medicaid; instead, eligibility depends on the number, type, and extent of their functional needs.

Not all low-income people with dementia qualify for or are enrolled in Medicaid. Many people with dementia have low-incomes but are not covered by Medicaid. People may be ineligible due to not meeting financial eligibility or functional criteria. Over time, they may deplete their resources or income to meet their care needs or their functioning may deteriorate to the point where they do meet eligibility requirements. Alternatively, low-income people with dementia may be eligible but not aware that they qualify for Medicaid or may have difficulty navigating the application process. These people may attempt to rely on unpaid care from friends or family or pay for care out-of-pocket, which may be unsustainable over time as functioning declines. For an example of a senior with dementia whose functioning declined to the point where her needs could no longer be met by unpaid care from a family member, leading to her Medicaid application, see Text Box 1.

Text Box 1: Senior with Alzheimer’s disease is eligible for Medicaid as a result of her low income and functional limitations: Irene, age 70, Valrico, Florida

“At this point, anything helps . . . in retrospect, I would have applied for services earlier rather than later.” -Irene’s daughter, Julia

Julia cared for her mother, Irene, at home for five years before applying for Medicaid. While Irene remains in good physical health, she has Alzheimer’s disease, the most common type of dementia. Over the last year, Irene’s symptoms significantly worsened: she can no longer be safely left alone, and she needs help with a number of daily activities, such as dressing, preparing meals, and using the bathroom at night. These functional limitations are the types of needs that typically are assessed when determining whether an applicant meets a qualifying level of care for Medicaid eligibility.

Julia learned about Medicaid as an option for providing additional services for Irene through a local Alzheimer’s support group, although she delayed initiating the application process, in part because she thinks she was in denial about the extent to which Irene’s daily functioning had deteriorated. Julia thought that she could handle caring for Irene without assistance and did not anticipate how challenging this would be come as Irene’s disease progressed. Julia says that her own health has deteriorated as a result of the stress of her caregiving responsibilities.

Prior to Irene receiving Medicaid, Julia was paying out-of-pocket for a companion aide to help with Irene’s care, which she has difficulty affording due to Irene’s limited income and the fact that Julia left her job to move cross-county to care for Irene. Julia also believes that her mother now needs more care than the companion aide can provide and worries that Irene may fall or wander from the house. Now that she is eligible for Medicaid, Irene will receive 10 hours per week of in-home care, which Julia hopes will help Irene to continue living at home as long as possible.

SOURCE: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Medicaid Beneficiaries Who Need Home and Community-Based Services: Supporting Independent Living and Community Integration (March 2014).

Who is the population with dementia that is covered by Medicaid?

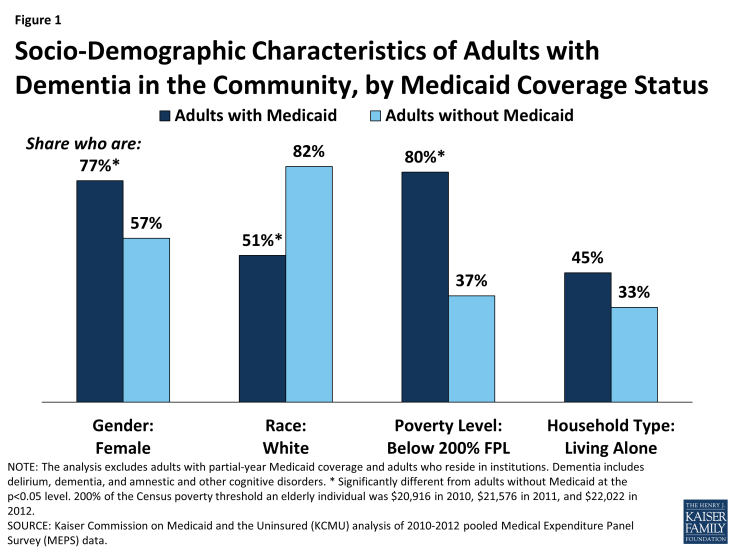

Medicaid beneficiaries with dementia differ from those who are not covered by Medicaid by gender, race, and income (Figure 1). Medicaid beneficiaries with dementia are more likely to be female and are more racially diverse than the non-Medicaid population with dementia. Unsurprisingly, given Medicaid’s financial eligibility criteria, Medicaid beneficiaries with dementia are more likely to have low incomes than those who are not covered by Medicaid. Consequently, Medicaid beneficiaries with dementia have few financial resources available to pay for care out-of-pocket. In addition, because nearly half (45%) of Medicaid beneficiaries with dementia live alone, they may not have regular access to unpaid caregiving from a family member.

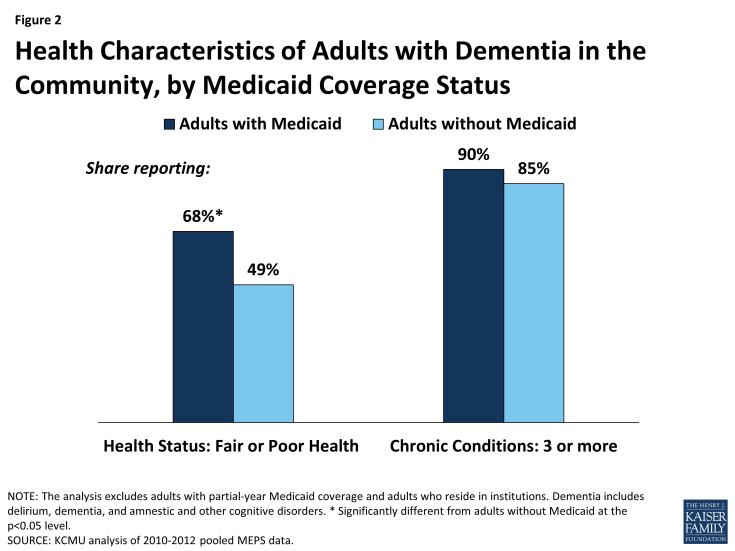

Medicaid beneficiaries with dementia are more likely to report being in fair or poor health compared to those without Medicaid (Figure 2). Given their reported poorer health status, Medicaid beneficiaries may need more intensive care and/or a broader scope of services to manage their greater health needs. Nearly all Medicaid beneficiaries with dementia (90%) have multiple chronic health conditions, indicating that they may benefit from care coordination services and/or efforts to better integrate medical, behavioral health, and long-term services and supports.

Figure 1: Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Adults with Dementia in the Community, by Medicaid Coverage Status

Figure 2: Health Characteristics of Adults with Dementia in the Community, by Medicaid Coverage Status

What services does Medicaid cover for people with dementia?

Though most Medicaid beneficiaries with dementia are dually eligible for Medicare, Medicare does not cover all of the services, particularly LTSS, that they may need. Medicare is the primary payer for dual eligible beneficiaries, with Medicaid providing wrap-around services and filling in coverage gaps.14 States participating in Medicaid are required to cover certain services and may provide other services at state option.15 Beneficiaries receive services based on medical necessity. Mandatory Medicaid services that may be relevant to people with dementia include inpatient and outpatient hospital services; lab and x-ray; nursing facility services; home health aide services, including durable medical equipment; physician services; and non-emergency medical transportation. Optional Medicaid services that may be relevant to people with dementia include prescription drugs; physical therapy and related services, including speech-language and occupational therapy; private duty nursing; personal care services; hospice; case management; adult day health care programs; and respite services. In addition, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) offers states a new option, Community First Choice, to provide attendant care services and supports with enhanced federal matching funds; as of September 2015, five states (CA, MD, MT, OR, and TX) offer these services.16

Some states have taken advantage of the ACA’s Medicaid health homes option to target services to people with dementia. The ACA provides time-limited enhanced federal funding for states to offer health home services, such as case management, care coordination and health promotion, transition services from inpatient to other settings, individual and family support, referrals to community and social support services, and the use of health information technology to link services for beneficiaries with chronic conditions. Some states, such as Alabama, Michigan, New York, and Washington, include dementia as a qualifying condition for enrollment in their health home programs, and other states offer health home services to people with delusional or chronic cognitive conditions.17, 18

Medicaid beneficiaries with dementia may qualify for home and community-based services (HCBS) waivers,19 some of which may include services targeted to people with dementia. For example, Massachusetts has a waiver that offers dementia coaching services and aims to divert frail, elderly beneficiaries from nursing facilities by providing services to support them in the community; the services offered by this waiver are listed in Text Box 2.20 Virginia also has a waiver targeted to people with dementia, which is limited to assisted living facility services.21 Unlike Medicaid state plan services, states can place enrollment caps on waiver services, which may result in waiting lists.22 HCBS are not necessarily medical in nature and aim to help individuals with LTSS needs, including those with dementia, reside in the community versus institutions. For an example of a senior with dementia who relies on Medicaid HCBS to live at home, see Text Box 3.

Text Box 2: Home and Community-Based Services Included in Massachusetts’ Frail Elder Waiver

- Alzheimer’s/dementia coaching

- Chore services (such as minor home repairs or maintenance)

- Companion services (such as non-medical supervision and socialization)

- Environmental accessibility adaptation

- Grocery shopping and delivery

- Home based wandering response systems

- Home delivered meals

- Home delivery of pre-packaged medication

- Home health aide

- Homemaker services

- Laundry

- Medication dispensing system

- Occupational therapy

- Personal care services

- Respite care

- Skilled nursing services

- Supportive day program

- Supportive home care aide (such as escort services)

- Transitional assistance for beneficiaries moving from institutions to the community

- Transportation services

Text Box 3: Medicaid provides necessary services to support senior with dementia living in the community: Mary, age 72, Kernersville, North Carolina

“Waiver services help me take care of my mother better and make her life as comfortable and easy as possible.” -Mary’s daughter, Karen

Mary’s dementia has worsened since her diagnosis a couple of years ago; she is not always able to recall the current date and day of the week, but she remembers her name and birth date and recognizes her daughter, Karen. In addition to dementia, Mary has multiple chronic conditions, including renal failure, diabetes, and a history of high blood pressure and strokes, and relies on a walker or wheelchair to get around.

Medicaid enabled Mary to move from an assisted living facility to Karen’s apartment. Medicaid now provides 47 hours of home health aide services per week to help Mary with preparing breakfast and lunch, dressing, and bathing while Karen is at work. Medicaid also paid for Mary’s bedside commode, bath bench, and wheelchair and provides incontinence supplies. Besides the services provided by Medicaid, Karen helps Mary with her personal hygiene at night, prepares her dinner, and helps get her ready for the day. Karen says that having Medicaid made Mary’s return home possible.

SOURCE: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Medicaid Beneficiaries Who Need Home and Community-Based Services: Supporting Independent Living and Community Integration (March 2014).

What is utilization and spending like for Medicaid beneficiaries with dementia?

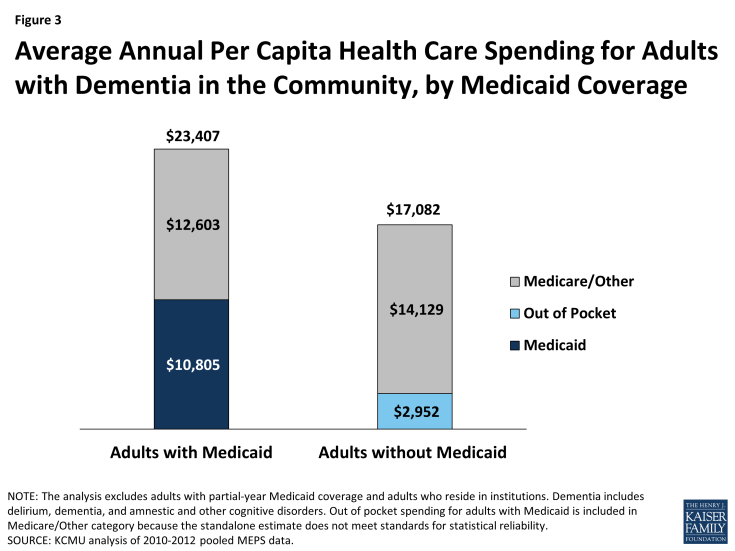

Medicaid plays an important role in covering the cost of home-based care for adults with dementia. For services covered by Medicare and other payers, adults with dementia who do and do not have Medicaid have similar utilization and spending patterns. For example, there were no significant differences between the two groups in the likelihood of having a usual source of care, number of office or inpatient visits, and number of prescriptions (Table 1). Similarly, average per capita total spending and Medicare/other payer spending for the two groups was not significantly different (Figure 3). However, adults with dementia who have Medicaid are significantly more likely than those without Medicaid to use home-based health services (Table 1); further, Medicaid pays an average of $10,805 for each adult enrollee with dementia each year (Figure 3), primarily for home-based services (data not shown). Since Medicare and most other payers have very limited coverage of home-based services, low-income adults with dementia are unlikely to be able to afford these services without assistance from Medicaid.

Figure 3: Average Annual Per Capita Health Care Spending for Adults with Dementia in the Community, by Medicaid Coverage

| Table 1: Health Care Access and Utilization Among Adults with Dementia Living in the Community, by Medicaid Coverage Status | ||

| Adults with Medicaid | Adults without Medicaid | |

| Have usual source of care | 90% | 91% |

| Average number of office visits in past year | 7.5 | 10.1 |

| Average number of inpatient visits in past year | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Average number of prescriptions filled in past year | 42.1 | 39.5 |

| Used any home health service in past year | 64%* | 39% |

| NOTES: The analysis excludes adults with partial-year Medicaid coverage and adults who reside in institutions. Dementia includes delirium, dementia, and amnestic and other cognitive disorders.

* Significantly different from adults without Medicaid at the p<0.05 level. SOURCE: KCMU analysis of 2010-2012 pooled MEPS data. |

||

Looking Ahead

Improving medical care and LTSS for people with dementia is likely to remain a major public health issue as well as the focus of ongoing medical research in the coming decades as policymakers, families, and other stakeholders consider cost-effective options to meet the needs of this vulnerable and expanding population. Medicaid beneficiaries with dementia have fewer financial resources to contribute toward the cost of care and are significantly more likely to use home-based services than people without Medicaid. People with dementia will likely need paid care as their functioning declines, and in the absence of other viable public or private financing options, Medicaid will continue to be the nation’s primary payer for LTSS.

A number of policy issues will inform ongoing efforts to improve health outcomes for Medicaid beneficiaries with dementia in a way that promotes inclusion, independence, and dignity. For example, people with cognitive impairments—such as difficulty communicating, understanding, or retaining new information—may face challenges with the complexities of the Medicaid application process. Special outreach, education, and counseling services could ease this process for people with dementia. States also may examine whether their functional needs assessment tools capture the full severity, scope, and duration of needs experienced by people with dementia as a result of a range of cognitive impairments.

In addition, new efforts in Medicaid service delivery may be targeted to people with dementia who live in the community. States now have several options through which they can provide Medicaid HCBS to meet the needs of beneficiaries with dementia. Efforts to integrate medical, long-term, and behavioral health services and supports may be particularly fruitful, given that most beneficiaries with dementia also have other chronic conditions. Further, as states develop programs, efforts could include developing dementia-specific measures to assess care quality, initiatives to ensure an adequate supply of direct care workers to meet this population’s needs, and dementia care training as part of provider credentialing to promote best practices.