The Uninsured at the Starting Line: Findings from the 2013 Kaiser Survey of Low-Income Americans and the ACA

III. Gaining Coverage, Getting Care

How New Insurance Coverage Could Change How People Use Health Care

Uninsured adults generally do not seek or receive health care services at the same rate as insured adults, even when they have a need for care. Many uninsured adults have substantial health care needs that are not monitored by a physician. Cost is the main reason the uninsured do not receive care when needed, and many lack a regular provider to facilitate follow-up or ongoing care. When uninsured adults do receive care, they often have limited options. As coverage expands under the ACA, uninsured adults are likely to get care more frequently and establish relationships with physicians. Patterns of care may shift, and providers may see an increase in patients who may have previously untreated or undiagnosed health care problems.

A large segment of the uninsured has little or no connection to the health care system.

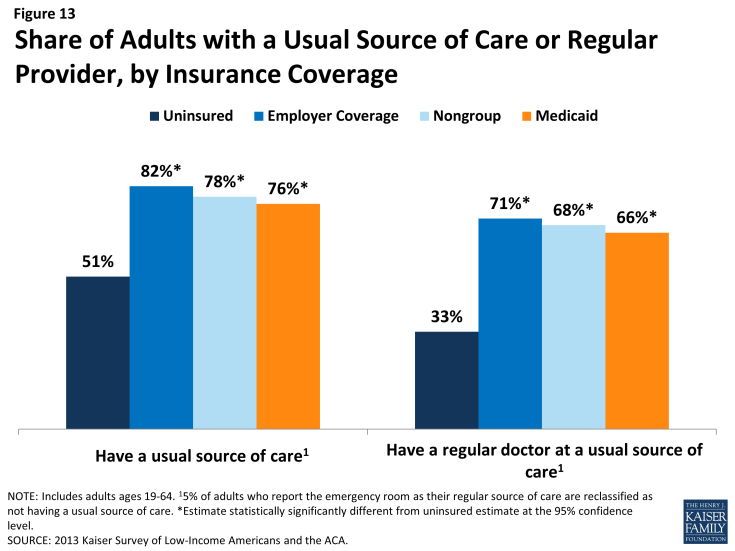

While some uninsured adults do report receiving health care services, most uninsured adults report few connections to the health care system. Only about half of uninsured adults (51%) report that they have a usual source of care, or a place to go when sick or need advice about their health (not counting the emergency room). Having a usual source of care is an indicator of being linked in to the health care system and having regular access to services. In comparison to the uninsured, most insured adults—82% of those with employer coverage, 78% of those with nongroup coverage, and 76% of those with Medicaid coverage— have a usual source of care (Figure 13). Uninsured adults also are less likely to have a regular doctor at their usual source of care – only 33% of uninsured adults have a regular doctor, half the rate of insured adults. Notably, low-income uninsured adults are the least likely to have a usual source of care or a regular physician (Table 3).

| Table 3: Share of Adults with Usual Source of Care or Regular Provider, by Income and Coverage | |||||

| Uninsured | Insured | ||||

| Employer | Nongroup | Medicaid | |||

| Has a usual source of care^ | |||||

| All | 51% | 82%* | 78%* | 76%* | |

| By Income | |||||

| <138% FPL | 49% | 67%* | 73%* | 74%* | |

| 139-400% FPL | 51% | 81%* | 69%* | 80%* | |

| >400% FPL | 67% | 85% | 89% | — | |

| Has a regular provider at usual source of care^ | |||||

| All | 33% | 71%* | 68%* | 66%* | |

| By Income | |||||

| <138% FPL | 27% | 56%* | 61%* | 64%* | |

| 139-400% FPL | 36% | 70%* | 56%* | 71%* | |

| >400% FPL | — | 74% | 84%* | — | |

| Notes: Don’t Know and Refused responses not shown. Excludes people covered by other sources, such as Medicare, VA/CHAMPUS, or other state programs. “–“: Estimates with relative standard errors greater than 30% or cell sizes below 50 are not provided. ^ 5% of adults who report the emergency room as their regular source of care are reclassified as not having a usual source of care. * Estimate statistically significantly different from uninsured estimate at the 95% confidence level. SOURCE: 2013 Kaiser Survey of Low-Income Americans and the ACA. |

|||||

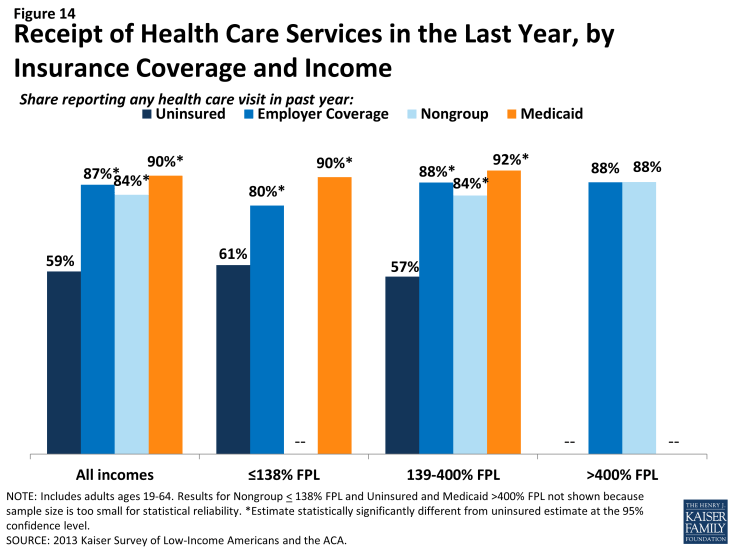

This lack of a connection to the health care system leads many uninsured adults to go without care. More than four in ten uninsured adults (41%) reported no health care visits (including hospital visits, doctors’ or clinic visits, mental health services, or trips to the emergency room) in the past year, compared to 10% of Medicaid beneficiaries and 13% of adults with employer coverage (Figure 14). This pattern holds across income groups. Of particular concern is the lack of preventive visits among the uninsured. Only 1 in 3 uninsured adults (33%) reported a preventive visit with a physician in the last year (data not shown), compared to 74% of adults with employer coverage and 67% of adults with Medicaid.

The survey findings reinforce conclusions based on prior research: having health insurance affects the way that people interact with the health care system, and people without insurance have poorer access to services than those with coverage.1,2,3 Thus, gaining coverage is likely to connect many currently uninsured adults to the health care system. However, outreach may be needed to link the newly-insured to a regular provider and help them establish a pattern of regular preventive care.

A substantial share of the uninsured has health needs, many of which are unmet or only met with difficulty.

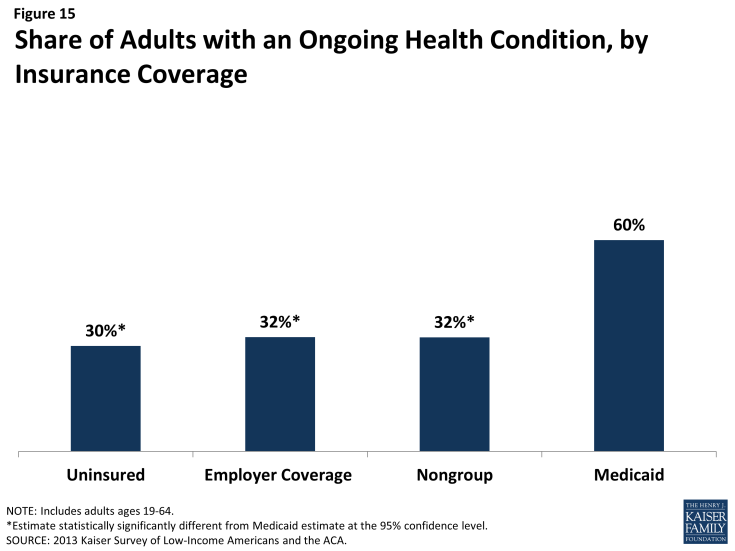

People who lack health insurance still have health care needs. In fact, uninsured adults in the survey were just as likely as those with private insurance to report having an ongoing health condition, with about 3 in 10 uninsured (30%) and privately insured adults (32% for both employer and nongroup coverage) reporting having an ongoing health condition (Figure 15). Given that the uninsured are more likely than people with coverage to have undiagnosed illness,4 actual rates of illness among the uninsured may be even higher. In contrast to those with private insurance, adults with Medicaid are twice as likely as uninsured adults to report having a health condition, with 60% of Medicaid beneficiaries reporting an ongoing health condition. This finding, which holds across income groups (Table 4) reflects Medicaid’s pre-ACA role in caring for people with substantial health needs (such as individuals with disabilities or people who become impoverished due to high health care expenses). As low-income uninsured gain coverage under reform, Medicaid’s role will expand to include a broader scope of the adult population.

| Table 4: Health Status of Adults by Income and Coverage | |||||

| Uninsured | Insured | ||||

| Employer | Nongroup | Medicaid | |||

| Fair or poor overall health | |||||

| All | 32% | 12%* | 14%* | 45%* | |

| By Income | |||||

| <138% FPL | 37% | 18%* | — | 47%* | |

| 139-400% FPL | 29% | 14%* | — | 35% | |

| >400% FPL | — | 9%* | — | — | |

| Fair or poor mental health | |||||

| All | 18% | 6%* | — | 34%* | |

| By Income | |||||

| <138% FPL | 21% | 12%* | — | 33%* | |

| 139-400% FPL | 18% | 9%* | — | 38%* | |

| >400% FPL | — | — | — | — | |

| Have an ongoing health condition that needs to be monitored regularly or needs regular care |

|||||

| All | 30% | 32% | 32% | 60%* | |

| By Income | |||||

| <138% FPL | 32% | 23%* | — | 63%* | |

| 139-400% FPL | 29% | 30% | 33% | 50%* | |

| >400% FPL | — | 36% | 27% | — | |

| Take prescription medication on regular basis^ | |||||

| All | 28% | 42%* | 45%* | 71%* | |

| By Income | |||||

| <138% FPL | 31% | 34% | — | 71%* | |

| 139-400% FPL | 28% | 37%* | 43% | 74%* | |

| >400% FPL | — | 47% | 45% | — | |

| Notes: Don’t Know and Refused responses not shown. Excludes people covered by other sources, such as Medicare, VA/CHAMPUS, or other state programs. “–“: Estimates with relative standard errors greater than 30% or cell sizes below 50 are not provided. ^ Excludes birth control. * Estimate statistically significantly different from uninsured estimate at the 95% confidence level.Source: 2013 Kaiser Survey of Low-Income Americans and the ACA. |

|||||

While uninsured individuals with an ongoing health condition are more likely than those without to report receiving services (Figure 16), they are still less likely than their insured counterparts to receive care. Half (50%) of uninsured adults without an ongoing health condition, received services in the past year compared to 81% of uninsured adults with a health condition. However, this rate is still lower than adults who have a health condition and have employer coverage, nongroup coverage, or Medicaid, nearly all of whom (97%, 96%, and 95%, respectively) received medical services over the course of the year.

Figure 16: Receipt of Health Care Services in the Last Year, by Insurance Coverage and Health Status

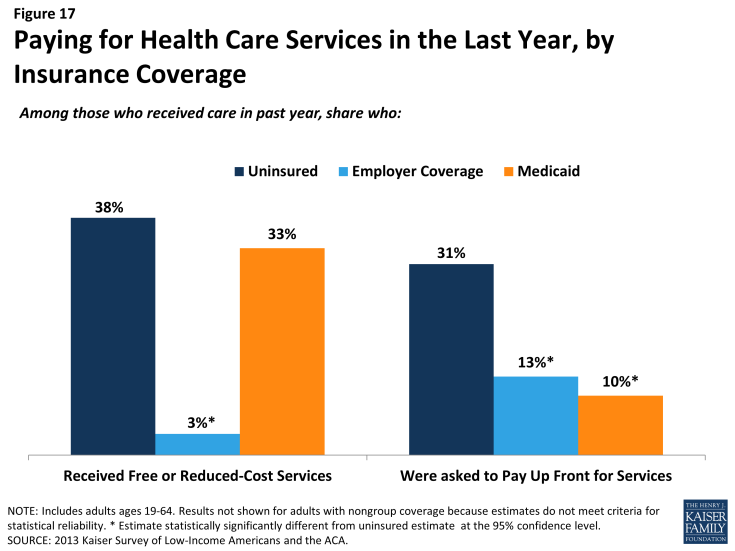

When uninsured individuals do receive care, they sometimes receive free or reduced-cost care, though the majority who use services do not. Among adults who reported that they received a health care service in the past year, 38% of uninsured adults report receiving free or reduced cost care, versus just 3% of those with employer coverage (Figure 17). Notably, about a third of adults with Medicaid who received services reported that they received free or reduced cost care. They may have done so during a period of uninsurance in the previous year or may associate the fact that they pay little or no costs when they see a provider as receiving “free or reduced cost” care. Uninsured adults who received care were much more likely than their insured counterparts to be asked to pay up front for care: nearly a third (31%) report being asked to pay for the full cost of medical care (not counting copayments) before they could see the doctor or provider, versus just 13% of those with employer coverage and 10% of adults with Medicaid. Again, insured adults may have experienced these issues during a period in the past year when they lacked coverage.

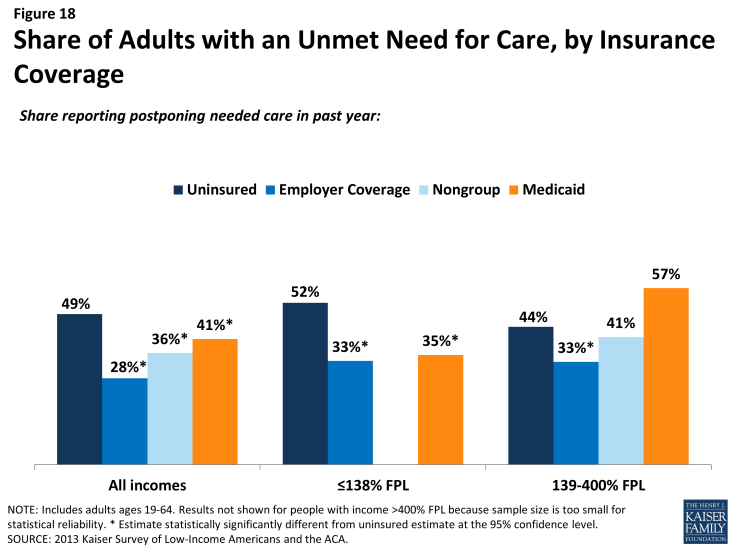

Despite some uninsured adults reporting that they receive free or reduced cost services, a larger share report an unmet need for care. Almost half (49%) of the uninsured report needing but postponing care compared to 28% of adults with employer coverage, 36% with nongroup coverage, and 41% of Medicaid beneficiaries (Figure 18). The relatively high rate among Medicaid beneficiaries reflects higher need: among Medicaid beneficiaries without a disability or ongoing health condition, rates of unmet need are similar to adults with other sources of coverage (data not shown).

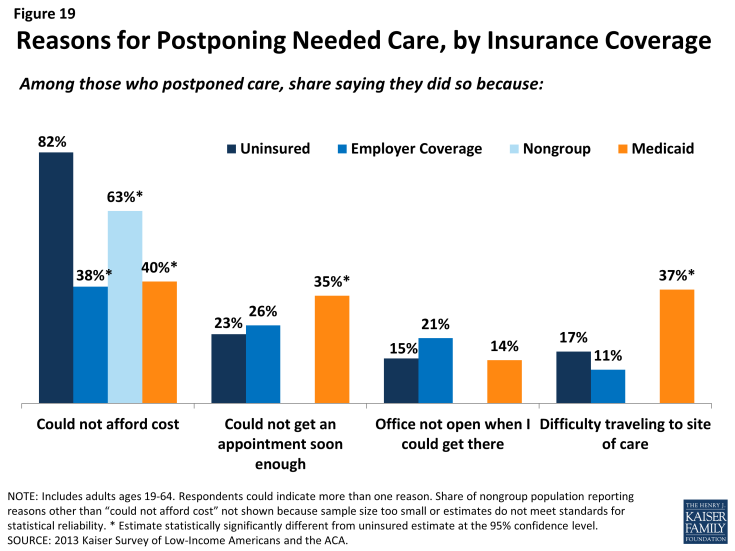

The most common reason for postponing care among the uninsured is cost, as the uninsured must pay the full cost of their care. Adults with employer coverage (38%), nongroup coverage (63%) or Medicaid (40%) are less likely to report cost as a reason for postponing care because presumably their insurance pays most or all of that cost (Figure 19). However, adults with Medicaid were more likely than other adults to report that they postponed care because they were unable to get an appointment soon enough or because they had difficulty traveling to the doctor’s office or clinic. These issues may reflect problems with provider participation in Medicaid, limits on Medicaid coverage of transportation services, or transportation barriers unique to the low-income population (such as not having a car). The only barrier that adults with employer coverage were more likely than other adults to report is the clinic or doctor’s office not being open at times when they could get there. This issue is a particular challenge for low-income workers, who often lose income when they take time off for a medical appointment during the day.

Given the health profile of the currently uninsured population, there is likely to be some pent-up demand for health care services among the newly-covered. Health systems may see increases in adults seeking care and will need to prepare for the newly insured. As people gain coverage under the ACA, the cost barriers to health care services will be reduced, but other barriers such as transportation or wait times for appointments may remain. The ACA included funds to expand service capacity in medically underserved areas, including expansion of community health centers, nurse-managed health centers and school-based clinics. To meet the health care needs of both insured and uninsured individuals, it is important that these systems develop flexible treatment times to accommodate people’s availability and expand capacity in areas where low-income individuals reside or seek care.

Many of the uninsured report limited options for receiving health care when they need it.

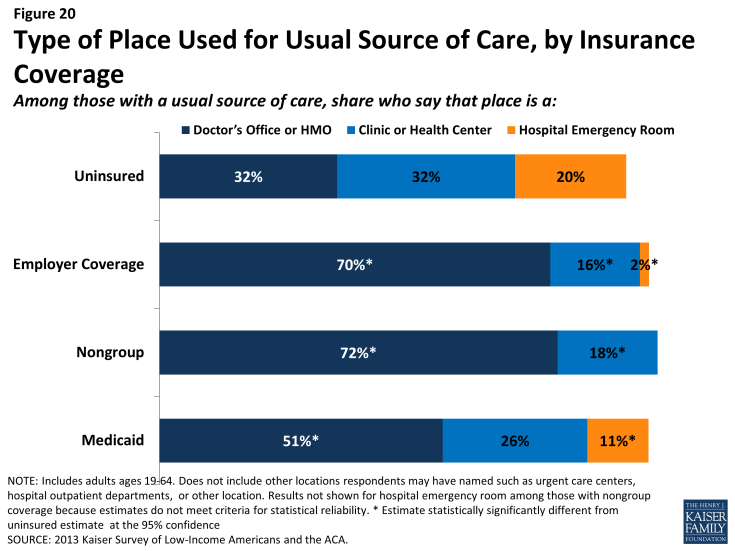

Uninsured adults are less likely than their insured counterparts to receive care in a private physician office when they do get care. About a third of uninsured adults (32%) report that a physician’s office or HMO is their regular source of care, compared to 70% of adults with employer coverage and more than half with Medicaid or other coverage (Figure 20). A third of uninsured adults who have a regular source of care (32%) report clinics or health centers as their usual source of care, twice as high as adults with employer coverage (16%). Notably, 20% of uninsured adults report the emergency room as their usual source of care – almost double the share of adults with Medicaid and ten times higher than adults with employer coverage (2%).

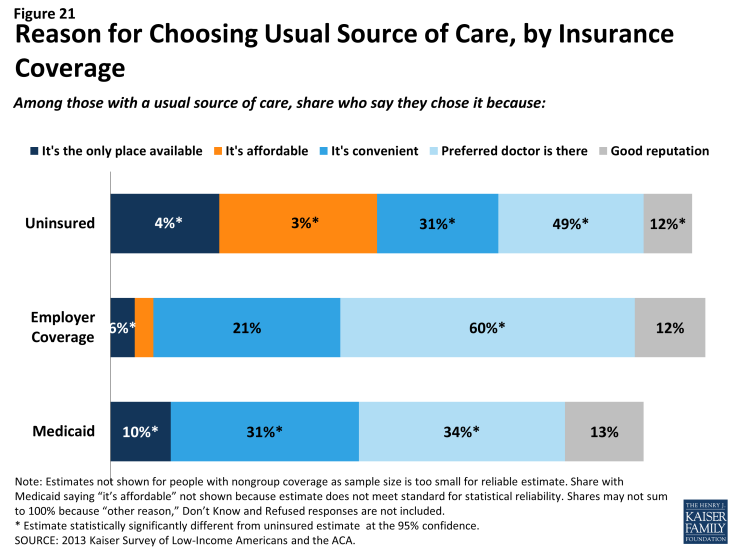

Uninsured adults are more likely than other adults to report that they have limited options for their usual source of care. Among people with a usual source of care, 18% of uninsured people report that they chose their usual source of care because it is the only option available to them, compared to 10% of adults with Medicaid and 4% with employer coverage (Figure 21). Of uninsured adults who say they had only one choice for care, almost half say that choice was the emergency department (data not shown). Uninsured adults are also more likely than other adults to choose their usual source of care because it’s affordable and less likely than other adults to choose their site of care because of convenience or ability to see their preferred provider. Most of those who say they chose their usual source of care based on cost say they chose a clinic or health center, reflecting that these providers often have a mission to serve low-income populations and offer services on a sliding scale.5

Based on the experience of their insured counterparts, the uninsured may have more options for where to receive their care once they obtain coverage under the ACA. Clinics and hospitals that already see a large share of uninsured adults may play an important role in enrolling this population in coverage and serving them once they gain insurance. However, these providers’ ongoing role—and people’s continuity of treatment— will depend in part on whether they are included in plan networks under both Medicaid and Marketplace plans. Further, many uninsured adults live in medically underserved areas, and it will be important to monitor whether coverage provisions are accompanied by delivery system reforms and new resources for primary care to expand access. Some individuals who have relied on emergency rooms or urgent care centers as their usual source of care may require help in establishing new patterns of care and navigating the primary care system. Last, in states that do not expand Medicaid, clinics and hospitals may continue to see high levels of the uninsured population and will remain the “safety net” for people who lack financial resources but need care.