Implementing Coverage and Payment Initiatives: Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2016 and 2017

Benefits and Pharmacy

| Key Section Findings |

Tables 17 and 18 provide complete listings of Medicaid benefit changes for FY 2016 and FY 2017. Table 19 provides additional details on Medicaid pharmacy benefit management strategies for opioids in FFS programs in FY 2015-FY 2017. |

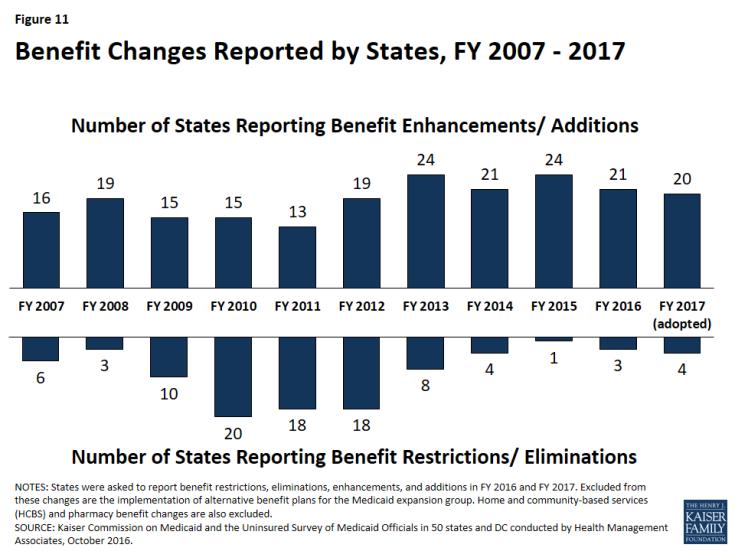

In this year’s survey, the number of states reporting benefit cuts or restrictions – three in FY 2016 and four in FY 2017 – is comparable to the number reporting cuts in last year’s survey, but remains far below the number seen during the economic downturn. A far larger number of states, 21 states in FY 2016 and 20 in FY 2017, reported enhancing or adding new benefits (Figure 11).

The most common benefit enhancements or additions reported were for behavioral health and/or substance use disorder services, telemedicine and tele-monitoring services, and dental services (Exhibit 12).

| Exhibit 12: Benefit Enhancements or Additions | ||

| Benefit | FY 2016 | FY 2017 |

| Behavioral Health/Substance Use Disorder | MT, NH, NY, SC, TX, VT, WY | DC, HI, NE, NJ, RI, TX, VA |

| Telemedicine / Tele-monitoring | DC, GA, NV, NY, OK, VT | NE, RI, TX |

| Dental Services | MT, NY | AZ, MD, OR, VT |

California and Michigan implemented other notable benefit expansions in FY 2016. California expanded benefits to provide the full Medicaid benefit package to pregnant women between 60 and 138 percent FPL in place of the former, more limited pregnancy-related benefit package. As part of its Section 1115 waiver to expand coverage to additional children and pregnant women with lead exposure from tainted water in Flint, Michigan implemented Targeted Case Management services for waiver enrollees. For FY 2017, other notable benefit expansions include Oregon’s expanded coverage for alternative back therapies including acupuncture, chiropractic manipulation and yoga (to reduce reliance on medications and surgeries) and Rhode Island’s new “STOP” (Sobering Treatment Opportunity Program) pilot. This ER diversion pilot in Providence will cover an overnight stay and referral to appropriate counseling for certain homeless individuals.

Benefit restrictions reflect the elimination of a covered benefit or the application of utilization controls for existing benefits. Most benefit restrictions in FY 2016 and FY 2017 were narrowly targeted; however, in FY 2017, Wyoming reported plans to adopt several benefit reductions and eliminations including: eliminating non-emergency adult dental and vision coverage, reducing nursing facility bed-hold days, and applying soft service caps for behavioral health, therapy, and home health services.

Tables 17 and 18 provide state-level information on benefit changes in FY 2016 and FY 2017.

| Autism Services |

| On July 7, 2014, CMS issued an Informational Bulletin1 describing approaches and Medicaid authorities available to cover Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) services. The bulletin also clarified state obligations under the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment (EPSDT) benefit to cover all medically necessary services for children, including ASD services. A number of states reporting adding coverage for ASD services, but because these policy changes were required they were not counted as positive or negative. |

Table 17: Benefit Changes in the 50 States and DC, FY 2016 and FY 2017

| States | FY 2016 | FY 2017 | ||

| Enhancements/ Additions | Restrictions/ Eliminations | Enhancements/ Additions | Restrictions/ Eliminations | |

| Alabama | ||||

| Alaska | X | |||

| Arizona | X | X | ||

| Arkansas | X | |||

| California | X | X | ||

| Colorado | X | |||

| Connecticut | X | |||

| Delaware | ||||

| DC | X | X | ||

| Florida | ||||

| Georgia | X | |||

| Hawaii | X | |||

| Idaho | ||||

| Illinois | ||||

| Indiana | ||||

| Iowa | ||||

| Kansas | X | |||

| Kentucky | ||||

| Louisiana | X | |||

| Maine | ||||

| Maryland | X | X | ||

| Massachusetts | X | |||

| Michigan | X | |||

| Minnesota | X | |||

| Mississippi | ||||

| Missouri | X | |||

| Montana | X | |||

| Nebraska | X | |||

| Nevada | X | X | ||

| New Hampshire | X | X | ||

| New Jersey | X | |||

| New Mexico | ||||

| New York | X | X | ||

| North Carolina | ||||

| North Dakota | ||||

| Ohio | ||||

| Oklahoma | X | X | X | X |

| Oregon | X | |||

| Pennsylvania | ||||

| Rhode Island | X | |||

| South Carolina | X | |||

| South Dakota | X | |||

| Tennessee | X | |||

| Texas | X | X | ||

| Utah | X | |||

| Vermont | X | X | ||

| Virginia | X | |||

| Washington | X | |||

| West Virginia | ||||

| Wisconsin | ||||

| Wyoming | X | X | X | |

| Totals | 21 | 3 | 20 | 4 |

| NOTES: States were asked to report benefit restrictions, eliminations, enhancements, and additions in FY 2016 and FY 2017. Excluded from these changes are the implementation of alternative benefit plans for the Medicaid expansion group. Home and community-based services (HCBS) and pharmacy benefit changes are also excluded. SOURCE: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured Survey of Medicaid Officials in 50 states and DC conducted by Health Management Associates, October 2016. |

||||

Table 18: States Reporting Benefit Actions Taken in FY 2016 and FY 2017

| State | Fiscal Year | Benefit Changes |

| Alaska | 2017 | Children (+): Will expand availability of Applied Behavioral Analysis services by developing new ABA provider certification requirements. |

| Arizona | 2016 | Adults (+): Remove limits on coverage for certain orthotic devices (October 1, 2015). |

| 2017 | Adults (+): Add coverage for podiatry services (August 6, 2016).

LTSS Adults (+): Add a $1,000 per year dental benefit for MLTSS enrollees (October 1, 2016). |

|

| Arkansas | 2017 | Expansion Adults (-): Eliminating non-emergency medical transportation coverage for expansion adults participating in Employer Sponsored Insurance feature of the Section 1115 waiver renewal. |

| California | 2016 | Pregnant Women (+): Expansion to full-scope coverage to pregnant women 60-133% FPL. |

| 2017 | All (+): Restored acupuncture services (eliminated in 2009 for most populations excluding children, pregnant women, and nursing facility residents) (July 1, 2016).

Pregnant Women (+): Added Licensed midwives to the Comprehensive Perinatal Services Program (July 1, 2016). All (+): Adding pulmonary and cardiac rehabilitation in outpatient settings (January 1, 2017). (Currently only available in inpatient settings.) |

|

| Colorado | 2016 | Children (nc): Added coverage for Applied Behavioral Analysis services for children with autism spectrum disorder to meet federal requirements (July 1, 2015).

Adults (+): Added coverage for iPads as augmented communication devices (ACDs) (July 1, 2015). |

| Connecticut | 2016 | Adults (+): Added coverage of select over the counter drugs (July 1, 2015).

Pregnant Women (+): Added coverage of low-dose aspirin (July 1, 2015). |

| District of Columbia | 2016 | All (+): Expanded coverage for telemedicine services. |

| 2017 | Children (+): Adding reimbursement for adolescent substance abuse treatment. | |

| Florida | 2017 | Persons with SMI or SUD (nc): Delivery of service changes for behavioral health – housing supports as part of the 1115 waiver. |

| Georgia | 2016 | Adults (+): Added coverage for medically necessary emergency transportation by rotary wing air ambulance.

All (+): Added coverage for Emergency Ambulances to serve as Telemedicine Origination Sites (April 22, 2016). |

| Hawaii | 2017 | Aged and Disabled (+): Expanding mental health and substance abuse benefits including addition of intensive case management and tenancy supports as part of chronic homelessness initiative (upon CMS approval). |

| Indiana | 2016 | Children (nc): Adding coverage for Applied Behavioral Analysis services for children with autism spectrum disorder to meet federal requirements (February 6, 2016). |

| Kansas | 2016 | Children (+): Expanded coverage for developmental therapy (OT/PT speech). |

| 2017 | Children (nc): Moving autism services from HCBS waiver coverage to State Plan coverage. | |

| Louisiana | 2016 | Pregnant Women (nc): Added coverage for free standing birthing centers (an ACA requirement) (December 20, 2015).

All (+): Removed limits on physician visits (December 20, 2015). |

| Maryland | 2016 | All (+): Added Physician Assistants as a new provider type (July 1, 2015). |

| 2017 | Children (nc): Adding coverage for Applied Behavioral Analysis services for children with autism spectrum disorder to meet federal requirements (January 1, 2017).

Former foster youth (+): Extending dental coverage for former youth up to age 26 (January 1, 2017). |

|

| Massachusetts | 2016 | Children (nc): Added coverage of Applied Behavioral Analysis services for children with autism spectrum disorder to meet federal requirements (July 1, 2015). |

| 2017 | All (+): Adding coverage of American Society of Addiction Medicaid Level 3.1 Residential Rehabilitation Services and Transitional Support Services (January 1, 2017). | |

| Michigan | 2016 | Children and Pregnant Women (+): Targeted Case Management services added for pregnant women and children covered under the Flint Michigan Section 1115 waiver (for persons served by the Flint water system) (May 9, 2016).

Children (nc): Expanded autism services from age 6 to age 21 (January 1, 2016). |

| Minnesota | 2016 | Children (nc): Added coverage for treatment of autism spectrum disorder to meet federal requirements (July 1, 2015). |

| 2017 | All (+): Adding coverage for community emergency medical technician services (January 1, 2017). | |

| Missouri | 2016 | Children (+): Adding coverage for asthma education and environmental assessment services. (upon CMS approval).

Children (nc): Added coverage for Applied Behavioral Analysis services for children with autism spectrum disorder to meet federal requirements (October 2015). |

| Montana | 2016 | Non-Disabled Adults (+): Added dental benefits with a limit of $1,125 per benefit year (July 1-June 30). Diagnostic, preventive, denture, and anesthesia services are excluded from the financial cap (January 1, 2016).

All (+): Removed limits on mental health therapy and occupational, speech and physical therapy (January 1, 2016). All (+): Age limits removed for Substance Use Disorder treatment services (January 1, 2016). |

| Nebraska | 2016 | Children (nc): Added coverage for Behavior Modification/Applied Behavioral Analysis services for children with autism spectrum disorder to meet federal requirements (October 1, 2015). |

| 2017 | Children (+): Adding coverage for Multisytemic Therapy/Family Functional Therapy (July 1, 2016).

All (+): Adding coverage for MH/SUD peer support services (January 1, 2017). All (+): Adding coverage for telehealth and tele-monitoring services (January 1, 2017). |

|

| Nevada | 2016 | All (+): Expanding coverage for telemedicine services to additional provider types and eliminating requirement for an origination site thereby allowing beneficiaries to access telemedicine services from home (December 1, 2015).

Children (nc): Added coverage for Applied Behavioral Analysis services for children with autism spectrum disorder to meet federal requirements (January 1, 2016). |

| 2017 | All (+): Added coverage for paramedicine services (July 1, 2016). | |

| New Hampshire | 2016 | Non Expansion Population (+): Enhanced the Substance Use Disorder benefit (to align with ABP) (July 1, 2016).

Expansion Adults (-): Eliminated coverage of non-emergent use of the ER (January 1, 2016). |

| New Jersey | 2017 | Non-Expansion Adults (+): Substance Use Disorder benefit from the state’s Alternative Benefit Package for expansion adults added for all other Medicaid enrollees (July 1, 2016). |

| New Mexico | 2017 | Pregnant Women (nc): Implementing coverage for Birthing Centers. |

| New York | 2016 | All (-): Discontinued coverage for viscosupplementation of the knee for an enrollee with a diagnosis of osteoarthritis of the knee (April 1, 2015 for FFS and July 1, 2015 for managed care).

All (-): Limited coverage of DEXA Scans for Screening to one time every 2 years for Women Over Age 65 and Men Over Age 70 (April 1, 2015 for FFS and July 1, 2015 for managed care). All (+): Expanded smoking cessation counseling providers to include dental practitioners (April 1, 2015 for FFS and July 1, 2015 for managed care). All (+): Expanded Telehealth services. All (+): Expanded Dental Hygienist services. Aged & Disabled (+): Added services for adults with serious mental illness services under 1915(i) authority as part of the state’s Health and Recovery Plans (HARP) managed care program. |

| Oklahoma | 2016 | Adults (-): Eliminated coverage for sleep studies (July 1, 2015).

All (+): Added coverage for virtual visits with annual limits (January 2016). All (+): Telemedicine policy rules around origination sites were removed. Patients no longer have to be at a specified “origination site” (e.g. they can now be in their homes). |

| 2017 | Children (+): Mandated polycarbonate lenses for children (September 1, 2016).

Pregnant Women (-): Reducing number of covered high risk OB visits based on utilization data (September 1, 2016). |

|

| Oregon | 2017 | Adults (+): Restoring previously cut adult restorative dental benefits (relaxed limitation criteria for dentures; coverage for crowns; scaling and planning) (July 1, 2016).

Adults (+): Expanding coverage for alternative back pain therapies including acupuncture, chiropractic manipulation and yoga (July 1, 2016). Children (nc): Added coverage for Applied Behavioral Analysis services for children with autism spectrum disorder to meet federal requirements (July 1, 2016). |

| Rhode Island | 2017 | All (+): Add coverage for home stabilization services.

All (+): Initiating coverage for Telehealth services in new MCO contracts. Aged and Disabled (+): Implementing the Sobering Treatment Opportunity Program (STOP), an ER diversion pilot in Providence that will cover an overnight stay and referral to appropriate counseling for homeless chronic inebriates. |

| South Carolina | 2016 | Children (+): Expanded coverage for treatment of eating disorders ages 0-21. |

| 2017 | Children (nc): Adding autism spectrum disorder treatment State Plan services to meet federal requirement; will replace existing HCBS waiver coverage that will sunset (January 2017). | |

| South Dakota | 2017 | Adults (+): Added coverage for BRCA gene testing (July 1, 2016). |

| Tennessee | 2017 | Adults (-): Limiting Allergy Immunotherapy to practice guidelines (July 1, 2016). |

| Texas | 2016 | Children (+): Added coverage for Prescribed Pediatric Extended Care Centers.

Children (+): Texas Health Steps Preventive Care Medical Checkups added mental health screening with separate reimbursement and screening for critical congenital heart disease (CCHD); updated laboratory screening policy for anemia, dyslipidemia and HIV screenings (11/1/2015). All (+): Added coverage for Magneto Encephalography (MEG) (November 1, 2015). Aged and Disabled (+): Expanded coverage for Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) services to include more providers in outpatient settings (July 1, 2016). All (+): Updated gynecological and reproductive health services coverage and reimbursement policy regarding IUD reimbursement and implantable contraceptive capsules (January 1, 2016). |

| 2017 | Children (+): Adding coverage for family therapy without the patient present as a benefit for children under 21. Pre-doctoral psychology interns and post-doctoral psychology fellows will be added as a recognized service provider when under delegation by a licensed psychologist.

All (+): Expanding coverage of tele-monitoring services to include congestive heart failure (CHF) and diagnoses related to high-risk pregnancy. |

|

| Utah | 2016 | Children (nc): Added autism spectrum disorder treatment to meet federal requirement (July 2015). |

| 2017 | Children (+): Eliminating the state’s Section 1115 EPSDT waiver which enables 19 and 20 year-old parents to be able to receive EPSDT services, which are not part of current 1115 waiver. | |

| Vermont | 2016 | All (+): Added coverage for Licensed Alcohol and Drug Counselors (July 1, 2015).

All (+): Added coverage for primary care telemedicine outside of a facility (October 1, 2015). Children (nc): Added coverage for Applied Behavior Analysis for treatment of autism spectrum disorder to meet federal requirements (July 1, 2015). |

| 2017 | All (+): Allowing Licensed Dental Hygienists to bill Medicaid directly (July 1, 2016). | |

| Virginia | 2017 | All (+): Under Section 1115 waiver authority, expanding Substance Use Disorder (SUD) services to add coverage of peer supports, inpatient residential for adults, and up to 15 days in an IMD in facilities with more than 16 beds (upon CMS approval).

All (+): Removing prior authorization requirements for low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) lung cancer screenings (July 1, 2016). |

| Washington | 2016 | All (+): Added coverage for gender reassignment surgery (August 6, 2015). |

| Wisconsin | 2016 | Children (nc): Added State Plan coverage (to replace HCBS waiver coverage) for behavioral health services for treatment of autism spectrum disorder to meet federal requirements (January 1, 2016). |

| Wyoming | 2016 | All (+): Added chiropractic benefit (July 1, 2015).

All (+): Added coverage for additional provisionally licensed MH provider types (July 1, 2015). |

| 2017 | All (+): Adding coverage for dietician services (July 1, 2016).

Adults (-): Eliminating dental and vision coverage (except emergency services) (October 1, 2016). LTSS Adults (-): Reducing Nursing facility bed-hold days (October 1, 2016). Adults (-): Adding soft service caps for behavioral health, therapy, and home health services (January 1, 2017). |

|

| NOTE: Positive changes counted in this report are denoted with (+). Negative changes counted in this report are denoted with (-). Changes that were not counted as positive or negative in this report, but were mentioned by states in their responses, are denoted with (nc). | ||

Prescription Drug Utilization and Cost Control Initiatives

Prior to the passage of the Medicare drug benefit, most states had implemented aggressive strategies to slow Medicaid spending growth for prescription drugs, including preferred drug lists (PDLs), supplemental rebate programs, and state maximum allowable cost (SMAC) programs. State focus on pharmacy cost containment diminished after nearly half of Medicaid drug spending shifted to the Medicare drug benefit in 2006. Since 2014, however, a disproportionate increase in prescription drug costs relative to overall spending has refocused state attention on pharmacy reimbursement and coverage policies. In this year’s survey, states reported a variety of actions in FY 2016 and FY 2017 to refine and enhance their pharmacy programs, including actions to react to new and emerging specialty and high-cost drug therapies.

Pharmacy Cost Drivers

This year’s survey asked states to identify the three biggest cost drivers that affected growth in total pharmacy spending (federal and state) in FY 2016 and projected for FY 2017. Consistent with the results from last year’s survey, the vast majority of states identified specialty and high cost drugs as the most significant cost driver.

Most states pointed specifically to hepatitis C antivirals as driving prescription drug costs; high costs are attributable to the high per prescription cost as well as increased utilization. In November 2015, CMS issued guidance to states regarding coverage policies for hepatitis C drugs. In that guidance, CMS expressed concern that some states were restricting access to these drugs contrary to statutory requirements and directed states to “examine their drug benefits to ensure that limitations do not unreasonably restrict coverage of effective treatment using the new direct-acting antiviral (DAA) hepatitis C drugs.”2 3 In May 2016, a federal court issued a preliminary injunction ordering Washington state to provide hepatitis C treatment to all Medicaid beneficiaries.4 This represents a turning point, as it was the first time a court declared restrictions to hepatitis C drugs based on disease severity illegal. A handful of states have eased restrictions in part due to an acknowledgement of the implications of the decision in Washington, as well other lawsuits and new guidance.

Other specialty drugs and behavioral health and/or substance use disorder drugs were cited as cost drivers, and some specific drug classes (such as hemophilia factor, oncology drugs, diabetes products, cystic fibrosis agents, and HIV drugs) were also identified as major cost drivers. In addition, states noted large price increases for existing generics and higher than expected prices for new generics entering the market as cost drivers.

Pharmacy Cost Containment Actions in FY 2016 and FY 2017

A majority of states had prescription drug cost containment policies (including prior authorization requirements and preferred drug lists (PDLs)) in place prior to FY 2016, and states are constantly refining and updating these policies. Although states may not have reported every refinement or routine change in this year’s survey, 31 states in FY 2016 and 23 states in FY 2017 reported implementing or making changes to a wide variety of cost containment initiatives in the area of prescription drugs, comparable to the number of states taking such actions in recent years. The most frequently cited actions were:

- New prior authorization requirements (12 states in FY 2016 and 6 in FY 2017),

- Updates or expansions of a PDL (10 states in FY 2016 and 4 in FY 2017), and

- Increased rebate collections (6 states in FY 2016 and 4 in FY 2017).

Multiple states also reported new or expanded Medication Therapy Management programs, imposing new quantity or dosage limits, implementing additional clinical claims system edits, specific drug carve-outs (e.g., hepatitis C antivirals), and updates or additions to State Maximum Allowable Cost programs. Also, two states (New Mexico and New York) described pharmacy “efficiency adjustments” that are applied during the MCO rate setting process to incentivize efficient pharmacy management by the MCOs.

| Medicaid Covered Outpatient Drug Final Rule |

| State Medicaid programs historically reimbursed pharmacies for the “ingredient cost” of each prescription using an Estimated Acquisition Cost (EAC), plus a dispensing fee.5 On January 21, 2016, CMS released the Covered Outpatient Drug final rule6 which, among other changes, replaces the term EAC with the term “Actual Acquisition Cost” (AAC) and also requires states to provide a “professional dispensing fee” that reflects the pharmacist’s professional services and costs to dispense a drug to a Medicaid beneficiary. States can define their own AAC prices or use the pricing files published and updated weekly by CMS – the “National Average Drug Acquisition Costs” (NADACs) – which are derived from outpatient drug acquisition cost surveys of retail community pharmacies.7 Some states had already transitioned to an AAC methodology prior to the issuance of the final rule. While this year’s survey did not ask specifically about state implementation of the Covered Outpatient Drug Rule, three states in FY 2016 and 16 in FY 2017 referenced implementation of the rule as a pharmacy cost containment action, suggesting that these states expected net savings from the AAC methodology change. One state referenced a cost neutral implementation of the rule, and one state listed the rule implementation as a cost driver for FY 2017. For purposes of this report, however, implementation of the Covered Outpatient Drug final rule is not counted as a cost containment action because it is an implementation of a federal regulatory requirement. |

Managed Care’s Role in Delivering Pharmacy Benefits

Since the passage of the ACA, states have been able to collect rebates on prescriptions purchased by managed care organizations (MCOs) operating under capitated arrangements. As a result, many states have chosen to “carve-in” the pharmacy benefit to their managed care benefits. As more states have enrolled additional Medicaid populations into managed care arrangements over time, and as Medicaid enrollment has increased due to ACA coverage expansions, MCOs have played an increasingly large role in administering the Medicaid pharmacy benefit. In this year’s survey, states with MCO contracts were asked whether pharmacy benefits were covered under those contracts as of July 1, 2016.

Thirty-three (33) of the 39 MCO states reported that the pharmacy benefit was “generally carved in.” Among the states that carved drugs in to MCOs, several reported carve-outs for selected drug classes. Behavioral health drugs (Maryland, Michigan, Oregon, and Utah), HIV drugs (Maryland and Michigan), hemophilia clotting factor (Michigan, New Hampshire, New York, Utah, and Washington), and hepatitis C antivirals (Michigan, New Hampshire, South Carolina, Washington, and West Virginia) were among the most common drugs carved out of MCOs. California referred generally to a select list of carved out drugs.

Four states (Colorado, Missouri, Nebraska, and Tennessee) reported that the pharmacy benefit was “generally carved out.” Nebraska noted that injectables were carved in and that a full carve in would be implemented in January 2017.

Two states reported variations by MCO program: Indiana reported that pharmacy was carved in for “HIP 2.0” (ACA expansion program) and “Hoosier Care Connect” (aged, blind and disabled program), but was currently carved out for Hoosier Healthwise (program for low-income pregnant women and children) until January 2017 when pharmacy would be carved in for this program too. Wisconsin reported that pharmacy was generally carved out except for its Family Care Partnership program (an integrated health and long-term care program for frail elderly people and people with disabilities) where it was carved in.

Prior reports show that nearly all states use prior authorization and PDLs in FFS programs. The survey asked about whether MCO contract requirements for uniform clinical protocols, a uniform PDL, or uniform prior authorization requirements were in place in FY 2015, added or expanded in FY 2016, or would be added or expanded in FY 2017 (Exhibit 13). This means that to the extent states impose or change these policies in FFS, the same policies would apply in managed care.

| Exhibit 13: Managed Care Pharmacy Policies | ||||||

| Policy | In Place in FY 2015 | New or Expanded | ||||

| FY 2016 | FY 2017 | |||||

| Uniform Clinical Protocols | 12 States | AZ, CA, GA, HI, IL, IN, KS, MA, NJ, PA, TX, WV | 6 States | DC, IA, KY, MA, MI, NY | 5 States | KY, MA, NE, NJ, NY |

| Uniform Prior Authorization Requirements | 9 States | AZ, GA, KS, MA, MS, NM, PA, TX, WV | 7 States | DC, IA, KY, MA, MI, NM, UT | 7 States | GA, KY, MA, NE, NM, UT, VA |

| Uniform PDL | 9 States | CA, DE, FL, KS, MA, MS, NH, TX, WV | 3 States | AZ, CA, IA | 3 States | MA, NE, UT |

Uniform Clinical Protocols

Twelve (12) states reported having uniform clinical protocol requirements in place in FY 2015, while six states in FY 2016 and five states in FY 2017 reported new or expanded clinical protocol requirements. These requirements were usually limited to specific drug classes. For example, several states mentioned particular drugs or drug classes including hepatitis C antivirals (Arizona, District of Columbia, Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania). A few states provided some additional details. In Iowa, MCOs are required to impose the same clinical edits8 as FFS; in Delaware, New Jersey and Texas, MCO clinical edits must be approved by the state; and Florida reported there were no specific protocols, but that MCO protocols may be no more restrictive than the FFS program policies.

Uniform Prior Authorization Requirements

Nine states reported having uniform prior authorization (PA) requirements in place in FY 2015, while seven states in FY 2016 and seven states in FY 2017 reported new or expanded uniform PA requirements. These requirements were usually limited to specified drug classes and in some cases overlap with the uniform clinical criteria responses described above (as states may use the PA process as a tool to enforce adherence to the states’ clinical criteria). For example, the District of Columbia and Virginia noted uniform PA requirements for substance use disorder drugs and New Mexico, Utah, and Virginia cited hepatitis C antivirals. Delaware and New Jersey noted that MCO PA requirements must be approved by the state.

Uniform PDL

Nine states reported having a uniform PDL requirement in place in FY 2015, while three states in FY 2016 and three states in FY 2017 reported new or expanded uniform PDL requirements. California reported that as its FFS formulary expanded over time, so have the MCO formularies. Massachusetts reported that the uniform PDL applied to a limited number of therapeutic classes. Louisiana reported that its five MCOs created a common PDL for selected drug classes which could be expanded by the MCOs in the future. One state (New Hampshire) reported eliminating its uniform PDL requirement in FY 2o16.

Other Managed Care Pharmacy Policies

Several states reported other managed care pharmacy policies. Kentucky reported that in FY 2016 FFS and the MCOs began to develop uniform PA forms (to make PA processes more manageable for providers) and align clinical criteria for high profile pharmaceutical products and disease states. In FY 2017, a Uniform Pharmacy Policy Committee in Kentucky will tackle topics such as access to hepatitis C treatment, opioid prescribing and limitations on utilization, and insect repellant coverage for Zika virus. Some states had strategies to mitigate the risk for certain drugs. For example, Hawaii, New Mexico, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Texas use risk corridor, risk pool, stop-loss arrangement and expense reimbursement for hepatitis C drugs; Pennsylvania reported risk sharing for cystic fibrosis drugs; Virginia reported a stop loss policy for any drug spending greater than $150,000 per member per year; and Washington reported an MCO PDL for antipsychotics.

Opioid Harm Reduction Strategies

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), overdose deaths from prescription opioid pain medications in the United States have more than quadrupled from 1999 to 2011.9 In addition to drug-related deaths, inappropriate opioid use causes other medical complications and suffering and has a disproportionate impact on Medicaid beneficiaries who are “prescribed painkillers at twice the rate of non-Medicaid patients and are at three-to-six times the risk of prescription painkillers overdose.”10 In a January 2016 Information Bulletin, CMS highlighted the important role state Medicaid programs can play to help address the opioid epidemic in their states by encouraging safer opioid alternatives for pain relief, working with other state agencies to educate Medicaid providers on best practices for opioid prescribing, employing pharmacy management practices (e.g., PDL placement, clinical criteria, prior authorization, quantity limits, etc.), and working to increase access to naloxone, an overdose antidote. In this year’s survey, states were asked about their opioid harm reduction strategies in place in FY 2015, implemented in FY 2016, and planned for FY 2017.

CDC Opioid Prescribing Guidelines

The CDC has developed and published recommendations for the prescribing of opioid pain medications for adults in primary care settings.11 This year’s survey asked states if their Medicaid program has adopted or is planning to adopt these guidelines in their FFS programs or as a requirement for MCOs to adopt. As shown in Exhibit 14 below, 21 states reported adopting the guidelines or plans to adopt in FY 2017 for their FFS programs. Of the 39 states with MCO contracts, 11 states reported requiring MCOs to adopt the CDC guidelines or plans to do so in FY 2017. Many states indicated these policies were under review for FFS and MCOs.

| Exhibit 14: Number of States Adopting CDC Opioid Prescribing Guidelines | ||||

| Status | For FFS | As a requirement for MCOs to adopt | ||

| Yes, have adopted | 7 States | AR, ID, MA, NE, NY, VA, VT | 2 States | MA, NY |

| Plan to adopt in FY 2017 | 14 States | AK, CT, DC, IA, LA, ME, MI, MS, NC, NH, OR, TN, WA, WV | 9 States | DC, IA, MS, NE, NH, OR, VA, WA, WV |

States were also asked to describe any implementation challenges related to the CDC guidelines. Some of the commonly reported challenges included system challenges; obtaining stakeholder consensus and support (including providers); titrating dosages downward for patients who have been stabilized on higher dosages; and the need for more provider education. A few states had state guidelines already in place that were aligned with the CDC guidelines.

Increasing Access to Naloxone

Naloxone is a prescription opioid overdose antidote that prevents or reverses the life-threatening effects of opioids including respiratory depression, sedation, and hypotension. Many states have taken steps to expand access to naloxone to enable family members and first responders to administer the antidote to save lives, including, for example, allowing “standing orders” or issuance of a statewide standing order that allows naloxone to be distributed by designated people, such as pharmacists or others meeting criteria established in the order. In this year’s survey, states were asked if their Medicaid program had implemented, or planned to implement, any initiatives to increase access to naloxone.

Half of the states (26) reported making naloxone (in at least one formulation) available without prior authorization or adding naloxone to their PDL. Some states (including Colorado and Michigan) reported expanding coverage of naloxone products beyond vials and syringes to include nasal spray and auto-injectors. Two states reported Medicaid coverage for naloxone prescribed to a family member or friend, and another state reported increasing access to naloxone by issuing a letter of direction to its MCOs.

Several states reported broader initiatives that are not specific or limited to Medicaid, including issuance or authorization of standing orders (6 states), allowing pharmacists to prescribe naloxone (3 states), third party prescribing laws that allow prescriptions to family members or friends (5 states), Good Samaritan laws that protect non-clinicians that administer naloxone (2 states); initiatives to educate and raise awareness (4 states), and making naloxone available without a prescription (3 states). According to a recent National Safety Council Report, however, a total of 35 states allow naloxone to be prescribed with a standing order and 35 states have enacted Good Samaritan provisions.12

Medicaid Pharmacy Benefit Management Strategies

The January 2016 CMS Informational Bulletin highlighted Medicaid pharmacy benefit management strategies for preventing opioid-related harms.13 The survey asked states to indicate whether one or more of these strategies was in place in FY 2015 for FFS and whether any changes to these strategies were made in FY 2016 or planned for FY 2017. Many states also have policies in place with regard to MCOs; however, it is unclear how many states require such policies to be in place.

Almost all states (44) took at least one action in FY 2016 or plan to take one action in FY 2017 to adopt or expand an opioid-focused pharmacy management policy in FFS. In FY 2015, 46 states imposed opioid quantity limits,14 45 states imposed prior authorization, 42 states had clinical criteria, and 32 states had step-therapy. (In some cases, the prior authorization actions reported may overlap with the responses regarding changes in opioid step therapy and/or clinical criteria as states may use the PA process as a tool to enforce adherence to the states’ clinical criteria and step therapy requirements.) Twelve states had a requirement that prescribers check the state’s Prescription Drug Monitoring Program before prescribing opioids. Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs) are state-run electronic databases that are valuable tools for addressing prescription drug diversion and abuse. Currently, with the exception of Missouri, every state operates a PDMP.15 16 Many states were newly implementing or expanding these programs in FY 2016 and FY 2017 (Exhibit 15 and Table 19).

| Exhibit 15: States Implementing Opioid-Focused Pharmacy Benefit Management Strategies in FFS | |||

| Strategy | In Place in FY 2015 (# of states) |

New or Expanded (# of states) | |

| FY 2016 | FY 2017 | ||

| Opioid Quantity Limits | 46 | 22 | 30 |

| Prior Authorization for Opioids | 45 | 18 | 27 |

| Opioid Clinical Criteria | 42 | 20 | 27 |

| Opioid Step Therapy Requirements | 32 | 13 | 20 |

| Required use of Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs | 12 | 10 | 11 |

Other Pharmacy Management Strategies. A few states mentioned other pharmacy management strategies in use or planned, including the following:

- Maryland and Mississippi reported provider and/or patient education efforts.

- New Jersey indicated that the medication assistance treatment (MAT) benefit already available to ACA expansion enrollees was expanded to all Medicaid enrollees July 1, 2016; Vermont cited its comprehensive “Hub and Spoke” MAT medical home program that provides broad access to anyone seeking treatment for substance use issues;

- Washington indicated that state law now requires consultation with a pain specialist for certain high dosage patients (greater than 120 morphine equivalent dose (MED));

- Alaska and Mississippi reported expanded Drug Utilization Review (DUR) activities that rely on PDMP access. Mississippi noted that its DUR program entered into a contract with the PDMP in 2016 to receive controlled substance claims for which Medicaid beneficiaries paid cash and those paid by Medicaid for monitoring purposes.

- In July 2016, Oregon Medicaid began covering various alternative treatment modalities (e.g., chiropractic, physical therapy, acupuncture, massage, yoga, and cognitive behavioral therapy), and has restrictions on the prescribing of opiates for back pain, neck pain, migraines, and fibromyalgia.

Table 19: Medicaid Pharmacy Benefit Management Strategies for Opioids in Fee-For-Service in All 50 States and DC, FY 2015 – FY 2017

| States | Opioid Quantity Limits | Prior Authorization for Opioids | Opioid Clinical Criteria | Opioid Step Therapy Requirements | Required use of Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs | ||||||||||

| In place FY 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | In place FY 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | In place FY 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | In place FY 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | In place FY 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

| Alabama | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Alaska | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Arizona | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Arkansas | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| California | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Colorado | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Connecticut | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Delaware | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| DC | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Florida | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Georgia | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Hawaii | |||||||||||||||

| Idaho | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Illinois | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Indiana | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Iowa | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Kansas | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Kentucky | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Louisiana | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Maine | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Maryland | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Massachusetts | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Michigan | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Minnesota | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Mississippi | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Missouri | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Montana | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Nebraska | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Nevada | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| New Hampshire | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| New Jersey | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| New Mexico | |||||||||||||||

| New York | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| North Carolina | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| North Dakota | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Ohio | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Oklahoma | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Oregon | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Pennsylvania | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Rhode Island | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| South Carolina | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| South Dakota | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Tennessee | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Texas | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Utah | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Vermont | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Virginia | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Washington | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| West Virginia | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Wisconsin | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Wyoming | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Totals | 46 | 22 | 30 | 45 | 18 | 27 | 42 | 20 | 27 | 32 | 13 | 20 | 12 | 10 | 11 |

| NOTES: States were asked to report whether they had select pharmacy benefit management strategies in place in their FFS programs in FY 2015, had adopted or expanded these strategies in FY 2016, or had plans to adopt or expand these strategies in FY 2017. SOURCE: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured Survey of Medicaid Officials in 50 states and DC conducted by Health Management Associates, October 2016. |

|||||||||||||||