2016 Survey of Health Insurance Marketplace Assister Programs and Brokers

Section 2: In-Person Assistance During Open enrollment

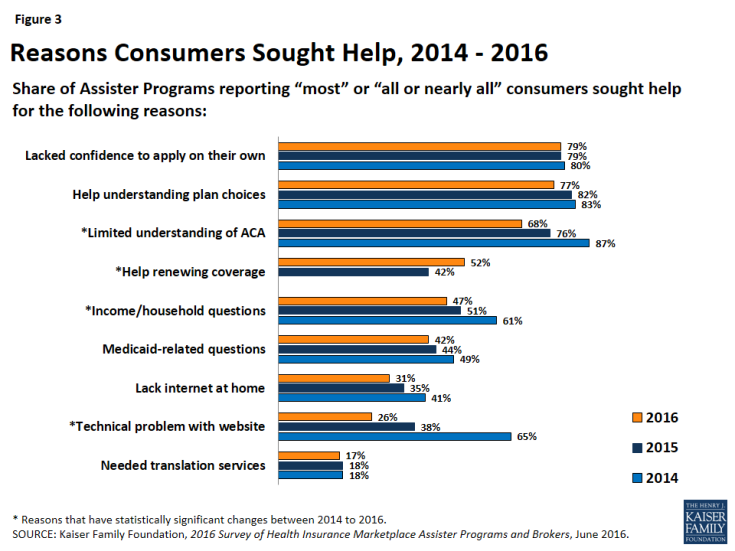

The need for in-person assistance remains strong. About eight in ten Assister Programs said most-to-nearly-all consumers sought help because they lacked confidence to apply for coverage and financial assistance on their own. As well, about eight in ten Programs said most-to-nearly-all consumers needed help evaluating plan choices. Fewer Assister Programs this year said that most consumers sought help with technical problems related to the Marketplace website, a sign that Marketplace IT systems continue to improve. But similar numbers report that most consumers also had problems with various aspects of the application process, including questions about how to report their income, family status, or citizenship/immigration status. There was a drop in the share of Programs reporting most clients had limited understanding of the ACA, though this remains a leading reason consumers seek help. In addition, this year there was an increase in Programs who said most of their clients sought help renewing coverage (Figure 3).

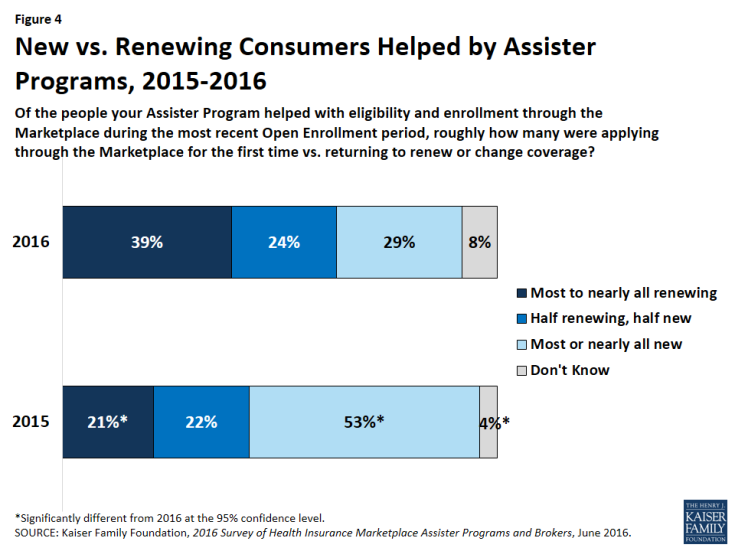

Enrollment assistance shifted toward renewing consumers in 2016. This year, renewing consumers made up a substantial share of the caseload for most Assister Programs. Twenty-nine percent of Assister Programs this year reported that most or nearly all consumers they helped were new to the Marketplace. By comparison, last year 53% of Assister Programs said most or nearly all consumers helped were new to the Marketplace (Figure 4). Although auto-renewal is an option, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) reported that 60% of plan renewals for 2016 were active renewals.1 This finding suggests many consumers believe they need in-person help to remain enrolled in Marketplace health plans and maintain their subsidies, not just to enroll for the first time.

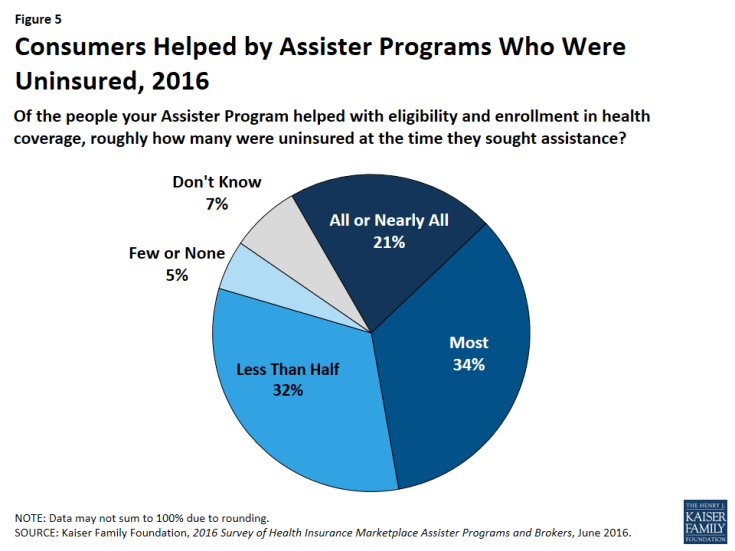

Even so, most who sought help during the third Open Enrollment were uninsured. This year, a majority of Assister Programs (55%) reported that most to nearly all of the consumers they helped were uninsured at the time they sought assistance. This is significantly lower than 83% of Programs last year and 89% of Programs in year one who said most people they helped were uninsured at the time they sought assistance (Figure 5). Even with the shift toward helping Marketplace enrollees renew coverage, a primary focus of Assister Programs continues to be on enrolling the uninsured.

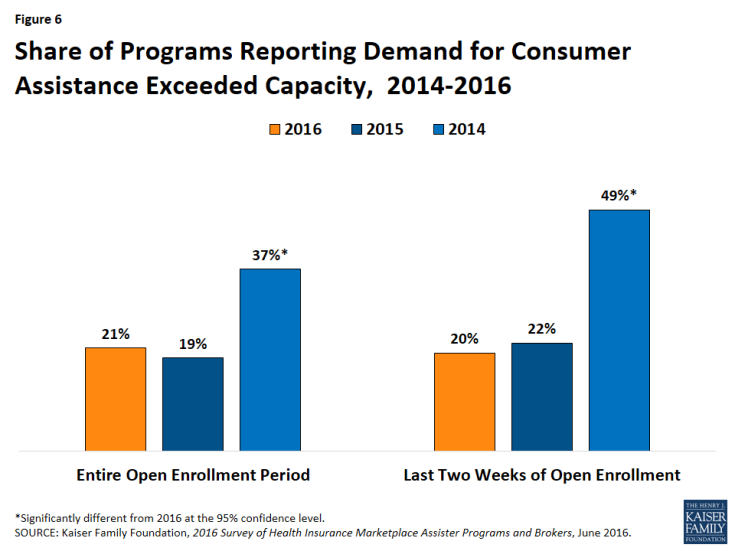

Demand for consumer assistance sometimes exceeded capacity. Twenty-one percent of Programs said they could not help all who sought it during the third Open Enrollment period overall. Similar numbers this year and last year had to turn away at least some consumers during the final weeks of Open Enrollment when a surge in demand always happens (Figure 6).

This year capacity to meet demand was especially stretched among large caseload Programs (30% had to turn at least some consumers away) compared to small caseload Programs (16%). Programs that reported a budget decrease in 2016 were more likely to say demand for help far exceeded capacity compared to Programs whose budget stayed the same or increased from the prior year (12% vs. 4%).

Eligibility and enrollment assistance remains time-intensive. As was the case in years one and two, Assister Programs reported that, on average, it took 90 minutes to help consumers who were applying to the Marketplace for the first time. In addition, like last year, Programs said it took one hour on average to help consumers who were returning to the Marketplace to renew or change coverage (Figure 7).

Why does the average time required for in-person help remain the same, even as Assisters and consumers gained experience and Marketplace websites have grown more reliable? The answer may lie in the inherent complexity of applying for coverage and financial assistance under the ACA. This year’s survey provides new data about specific aspects of the eligibility and enrollment process that can be challenging – real time verification by the Marketplace of applicants’ identity and application information, coordination between the Marketplace and state Medicaid programs, and the process of comparing and selecting Marketplace QHPs.

Real Time Verification by the Marketplace

On-line applications were expected to be easier and faster to complete because Marketplace websites would be able to verify consumer’s information in real time, matching it to other online databases. However, sometimes IT system problems, or the fact that some consumers don’t have matching information in the databases Marketplaces check, result in significant delays and may even pose a barrier to enrollment for some people.

Many consumers sought help with Marketplace identity-proofing requirements. To protect against enrollment fraud, Marketplaces first verify in real time the identity of applicants before they can submit an application for coverage and financial assistance. FFM states use an automated remote identity proofing process (RIDP) that compares applicant information against credit files and other online data sources. Many SBM states also use the federal RIDP system. One study found that certain groups of individuals are especially likely to have difficulty completing RIDP, including young adults and recent immigrants with limited credit history.2 The same study observed some SBM states have adopted alternatives or modifications to the RIDP system to streamline the process of proving one’s identity and expedite resolution of problems when they arise.

During the third Open Enrollment period, Assister Programs helped at least 230,000 consumers with identity-proofing problems. Depending on Program size, on average between 3% and 10% of consumers helped by Assister Programs during Open Enrollment encountered identity-proofing problems.

Overall, about 90% of Programs that helped consumers with identity proofing problems said they usually could help resolve them. Those in SBM states were more likely than in FFM states (22% vs. 14%) to say they usually could resolve problems quickly during the initial visit. This is probably because several SBM states use an alternative to RIPD. For example in Colorado and California, certified Assisters can visually verify an applicant’s identification document, upload a copy to the Marketplace, and then proceed immediately with the application.

Across all states, most Programs said that when identity proofing problems arose they usually added significantly to visit time or necessitated a follow up visit (Table 3). Programs in SBM states were less likely than in FFM states (3% vs. 10%) to say identity proofing problems usually could not be resolved. Across all Marketplaces, large caseload Programs were less likely than small Programs (3% vs 11%) to say these problems usually could not be resolved.

| Table 3: How did ID proofing problems affect the consumer’s application process? | ||||

| SBM Assister Programs | FFM Assister Programs | Large Caseload Programs | Small Caseload Programs | |

| We usually could resolve problem quickly during initial visit | 22% | 14%* | 14% | 17% |

| We usually could resolve problem during initial visit, but with significant additional time | 31% | 36% | 40% | 32%^ |

| We usually could resolve problem though at least one follow up visit was usually required | 44% | 40% | 42% | 39% |

| We usually could not resolve the problem | 3% | 10%* | 3% | 11% |

| *Significantly different from SBM programs at the 95% confidence level; ^Significantly different from Large Caseload programs at the 95% confidence level NOTE: Numbers may not sum to 100% due to rounding. |

||||

Overall, about one in four Assister Programs said they would like more training in resolution of online identity proofing problems. Large caseload Programs were twice as likely as small caseload Programs (35% vs 17%) to say they would like more training on this topic.

Many consumers sought help for Marketplace data match inconsistencies (DMI). Marketplaces also require real time verification of consumers’ citizenship or immigration status and income. Applicant information is matched against other online data, for example, held by the Social Security Administration, Department of Homeland Security, and Internal Revenue Service. When the Marketplace can’t verify application information online, consumers receive a notice of data match inconsistency (DMI) and are provided a temporary eligibility determination based on information they submitted. Consumers can enroll in coverage right away, but must provide additional documentation to the Marketplace within 90 days, otherwise their coverage or subsidies may be terminated. During 2015, the FFM terminated coverage for 500,000 individuals with citizenship or immigration DMI, and terminated or reduced premium tax credits and cost sharing subsidies for 1.2 million consumers with income DMI.3

Most Assister Programs said they helped consumers resolve DMI problems relating to immigration or citizenships during the third Open Enrollment. We estimate these Programs helped at least 172,000 consumers with immigration-related DMIs. In addition, most Programs reported helping consumers with DMI problems related to income. We estimate at least 259,000 consumers sought in-person help with income-related DMIs from these Programs.

In comparison to the number of FFM enrollees who could not resolve DMI problems last year and who lost coverage or subsidies as a result, these estimates suggest that either the number of consumers affected by DMI fell substantially this year, or most consumers with DMI are not getting help from Assister Programs.

Most Assister Programs will try to help consumers resolve DMI problems when they arise, though smaller Programs are more likely than large caseload Programs to refer consumers elsewhere for help or advise them to resolve inconsistencies on their own. In general, large caseload Programs were also more likely to know the resolution of their client’s DMIs compared to smaller Programs (Table 4).

| Table 4: Data Match Inconsistency Help by Assister Programs | |||

| All Programs | Large Caseload Programs | Small Caseload Programs | |

| Immigration DMI | |||

| Helped consumer and usually knew the resolution | 69% | 76% | 58%* |

| Helped consumer but mostly did not know the resolution | 19% | 20% | 23% |

| Referred consumer elsewhere or advised to solve on their own | 11% | 4% | 19%* |

| Income DMI | |||

| Helped consumer and usually knew the resolution | 72% | 80% | 62%* |

| Helped consumer but mostly did not know the resolution | 21% | 17% | 27% |

| Referred consumer elsewhere or advised to solve on their own | 7% | 3% | 11%* |

| *Significantly different from Large Caseload Programs at the 95% confidence level | |||

Marketplace notices about DMI may also present a challenge. For example, in case of an income-related DMI, FFM notices list examples of documents consumers might submit to verify different sources of projected income but do not specify which would be most appropriate for the individual applicant.4 With respect to DMI notices related to immigration or citizenship, 39% of Assister Programs said most of the time it was not clear what documentation the Marketplace wanted to the consumer to provide; 29% of Assister Programs responded this way with respect to income-related DMI notices.

One-in-five Assister Programs overall said they would like more training on the resolution of DMI problems. Large caseload Programs were more likely to want such training (about one in three) compared to small Programs (about one in seven).

Medicaid-Marketplace Coordination

Depending on the state, consumers also needed extra help enrolling in Medicaid. The ACA outlines a “no wrong door” approach to applying for coverage and requires a “single streamlined” application for financial assistance that can be used to determine eligibility for both QHP subsidies and Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). All 13 State-based Marketplaces that do not use healthcare.gov have integrated their eligibility systems with Medicaid, eliminating the need to transfer data between systems to make eligibility determinations for coverage. Eight FFM states allow healthcare.gov to determine Medicaid eligibility, though files are then transferred to state Medicaid agencies to complete enrollment.

In the remaining 30 states, healthcare.gov assesses Medicaid eligibility, then transfers the consumer’s file to the state Medicaid program for a final eligibility determination and to complete enrollment. Among Programs in states with integrated eligibility systems or in FFM determination states, 74% said the Medicaid enrollment process was usually completed in a timely manner. By contrast, 34% of Programs in assessment states said that the Medicaid eligibility determination was completed in a timely manner. To expedite the process, 44% of Programs in assessment states and 13% in determination states said they would help clients who were assessed eligible complete a separate Medicaid application.

Follow up interviews with Assister Program directors were conducted to learn why they created separate Medicaid applications. Some observed that direct applications were often processed faster than transferred files. Others cited difficulty in obtaining confirmation from healthcare.gov that transfers were successfully completed. Still others noted that applying directly to Medicaid in some states can also expedite application for other benefits, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. Some directors said they pre-screen consumers, then submit the application to the Marketplace or the state Medicaid portal depending on the coverage the individual will most likely be eligible for. Among Assister Programs that typically help consumers complete a separate Medicaid application, two-thirds said at least one additional follow up visit was needed to complete the separate application (Table 5).

| Table 5: When the Marketplace determined or assessed consumers eligible for Medicaid, what steps did you take next? | |||

| Action | All Programs | Determination states | Assessment states |

| Followed up with Medicaid until eligibility and enrollment was complete | 27% | 34% | 22%* |

| Helped consumer complete a separate Medicaid application | 31% | 13% | 44%* |

| Referred consumer to another Assister Program | 3% | 2% | 4% |

| Advised consumer to follow up with Medicaid on their own | 13% | 7% | 18%* |

| * Significantly different from Determination states at the 95% confidence level | |||

Comparing and Selecting Health Plans

The process of comparing and selecting health plans can also be complex. The sheer number of plan choices can be one reason. People living in FFM states, on average, had a choice of 50 Marketplace plans this year.5 Research on plan choice finds that having more than 10 options makes it harder for consumers to compare and evaluate.6 In addition, relatively small variations in QHPs can sometimes be meaningful to consumers. For example, while most QHPs (not modified by cost sharing reductions) have annual deductibles well in excess of $1,000 per person, many plans impose separate deductibles for at least some services, and many exempt key services, such as primary care visits, from the deductible.7,8 Another survey found that most consumers said it was somewhat or very easy to compare Marketplace plans generally; 74% found it easy to compare premiums, 69% found it easy to compare plan cost sharing features, and 60% found it easy to compare plan provider networks.9

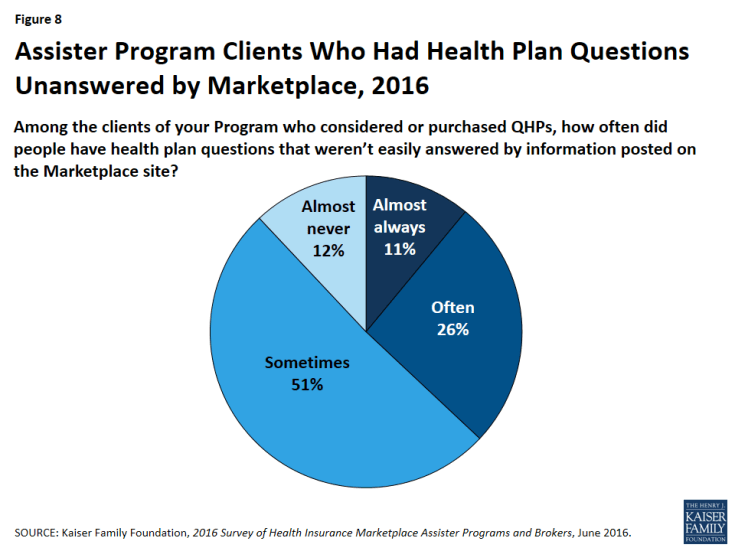

Marketplace health plan information sometimes leaves consumer questions unanswered. This year, 37% of Programs said consumers often or almost always had questions about health plans that were not answered by information on the Marketplace website (Figure 8). This is an increase from last year (31%) and attributable mostly to Programs in FFM states. Thirty-seven percent of FFM Programs this year, compared to 27% last year, said client’s health plan questions often were unanswered by information on healthcare.gov. Most Marketplaces have developed new plan comparison tools since the first Open Enrollment, for example, to sort options based on participating providers or to estimate consumer out-of-pocket expenses. For 2017, new standardized plan choices may be offered in the FFM to simplify plan comparison by consumers. Improvements to summary of benefits and coverage (SBC), a plain language summary of health plan provisions, were also approved and will be implemented in 2018. These changes may make it easier for consumers to understand and compare plan choices in the future.

One in four Assister Programs say they would like additional training on qualified health plan features and how to distinguish differences between plan options.

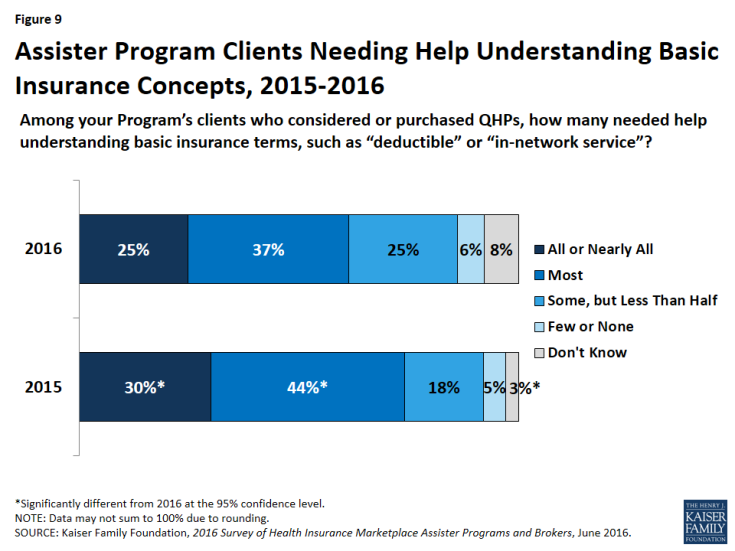

Insurance literacy limitations among consumers persist. This year most Assister Programs (62%) said most or almost all of their clients needed help understanding basic insurance terms and concepts such as “deductible” and “in-network service.” This is an improvement from 74% of Programs who answered this way in the first two years, though still evidence of widespread limitations (Figure 9). Three-in-ten Assister Programs would like additional training in health insurance literacy.

Assister Programs knew the plan choice for most/nearly all of QHP-eligible clients. This year again, when asked how often they knew the plan choice of their QHP-eligible clients, 71% of Assister Programs said this was the case for most or almost all such clients – the same number who reported this in year two and an increase over year one, when website breakdowns required Assisters to spend most appointment time helping consumers with the application. Large caseload Programs were more likely than smaller Programs to observe the plan choice for most or nearly all clients who were eligible for QHPs (82% vs. 62%). Two-thirds of Programs said most or nearly all of their QHP-eligible clients were able to complete the plan selection during the initial visit. The other 34% said clients typically required multiple visits.