The Current Ebola Outbreak and the U.S. Role: An Explainer

Key Points

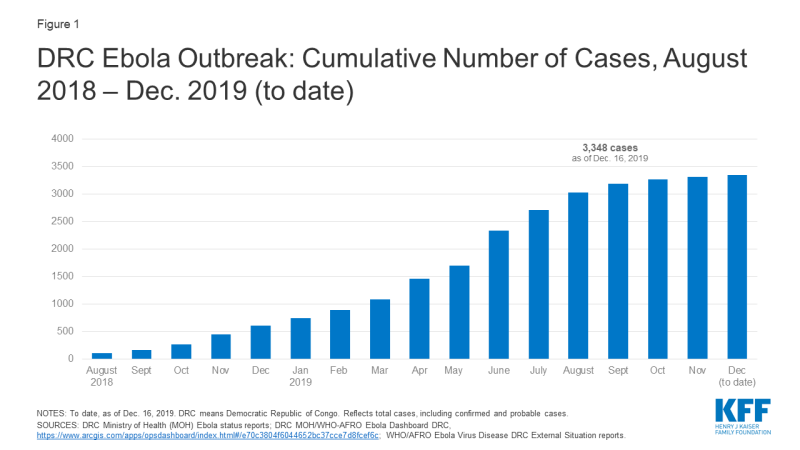

- More than 3,300 cases, including more than 2,200 deaths, have been reported to date in the ongoing Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), making it second only to the 2014-2015 West Africa outbreak that saw nearly 29,000 cases and claimed more than 11,300 lives. The outbreak has lasted a year and a half already, having been first declared by the DRC Ministry of Health on August 1, 2018. There are ongoing concerns about cross-border spread outside the DRC.

- Since July 2019, the outbreak has been considered a “public health emergency of international concern” (PHEIC) by WHO.

- Although the DRC has a history of successfully containing Ebola outbreaks and responders have access to new prevention tools such as an Ebola vaccine, multiple factors have impeded the response in the affected areas this time including violence and insecurity, community mistrust of government and external responders, funding constraints, and a complex political and socioeconomic operating environment.

- U.S. engagement has been limited compared to the 2014-2015 West Africa outbreak where the U.S. played a leading role and mobilized an unprecedented amount of funding, and personnel. In contrast, the U.S. has chosen to play a more limited role in this outbreak due partly to concerns about security, which have led the U.S. to restrict its personnel from working in the outbreak zone. Even so, the U.S. is the largest single international donor to the Ebola response effort in the DRC.

- The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), along with several other U.S. agencies, have provided technical and financial support to international response efforts in the DRC. A USAID Disaster Assistance Response Team (DART), which includes USAID and CDC staff, has been deployed to the DRC since September 2018.

- Policy questions for the U.S. government going forward include whether it will change its approach in order to allow government personnel to engage directly in frontline response activities and how it will support the transition from emergency response to longer-term support for improving health care in the affected areas.

Current Situation

When did the outbreak begin, and what countries are affected?

The current Ebola outbreak was first declared by the DRC Ministry of Health on August 1, 2018 (see timeline of key events below). Almost all cases of Ebola in this outbreak so far have occurred in the two northeastern DRC provinces of Ituri and North Kivu, though a few cases have recently been identified in South Kivu province. This outbreak is the tenth – and by far the largest – in the DRC’s history and the second largest Ebola outbreak ever recorded after the West Africa Ebola outbreak in 2014-2015 that saw 28,616 cases, including 11,310 deaths, in the three most affected countries (Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone).

Cross-border spread remains a concern. Uganda has reported several imported Ebola cases in areas bordering the DRC, with the most recent reported on August 26, 2019. WHO says there is a risk of further spread within the DRC and potentially across borders to Burundi, Rwanda, South Sudan, and Uganda, in particular. Several cases over the summer of 2019 in the large city of Goma, a regional and international transport hub that directly borders Rwanda, highlighted such concerns. Given the risks, neighboring countries have been preparing for possible cases for some time.

| Timeline of Key Events in Current Ebola Outbreak |

| August 1, 2018: Outbreak declared by the DRC Ministry of Health |

| Early August 2018: First U.S. CDC staff deployed to North Kivu province to assist in response efforts |

| August 7-8, 2018: Genetic tests confirm outbreak; vaccination efforts begin |

| August-September 2018: U.S. government pulls back staff from outbreak area due to security concerns |

| September 21, 2018: USAID deployed a Disaster Assistance Response Team (DART) to the DRC |

| October 17, 2018: WHO-convened Emergency Committee recommends that “public health emergency of international concern” (PHEIC) not be declared with regard to the DRC Ebola outbreak |

| November 9, 2018: Ebola case count surpasses largest number from previous DRC outbreaks, making this the largest Ebola outbreak in the DRC’s history |

| Late November 2018: Ebola case count surpasses all but the 2014-2015 West Africa outbreak, making this the second largest Ebola outbreak ever |

| Late December 2018: Voting in the DRC elections postponed in certain Ebola-affected areas, sparking protests |

| February 24, 2019: Ebola treatment center attacked and partially burned down, leading Medicins Sans Frontieres (MSF) to suspend services at the center; another center was attacked three days later, leading MSF to suspend its activities in the area |

| March 30, 2019: Ebola case count in this DRC outbreak surpasses 1,000 |

| April 12, 2019: WHO-convened Emergency Committee recommends for a second time that a PHEIC not be declared with regard to the DRC Ebola outbreak |

| April 15, 2019: The DRC Ministry of Health reports over 100,000 people have been vaccinated in this outbreak to date |

| April 19, 2019: WHO epidemiologist from Cameroon killed when a clinic was attacked in Butembo in the DRC |

| June 5, 2019: Ebola case count in the DRC outbreak surpasses 2,000 |

| June 11, 2019: Uganda confirmed first imported case of Ebola, with two additional cases reported the next day |

| June 14, 2019: WHO-convened Emergency Committee recommends for a third time that a PHEIC not be declared with regard to the DRC Ebola outbreak |

| July 14, 2019: The DRC government reports first case in Goma, capital of North Kivu province and a large city of 1-2 million people bordering Rwanda |

| July 17, 2019: WHO-convened Emergency Committee meets for a fourth time; WHO Director-General accepts the Committee’s assessment and declares the DRC Ebola outbreak a PHEIC |

| August 16, 2019: First Ebola cases confirmed in South Kivu province, the third province to see cases in this outbreak. |

| August 29, 2019: Ebola case count in the DRC surpasses 3,000; Uganda reports a fourth imported Ebola case |

| October 18, 2019: WHO Emergency Committee meets again and says the DRC outbreak remains a PHEIC. |

| November 11-12, 2019: Merck’s Ebola vaccine (Ervebo) approved by the European Commission and pre-qualified by WHO, making it the first officially licensed vaccine for Ebola. |

| November 14, 2019: Second Ebola vaccine (from Johnson & Johnson) is introduced into the Ebola response in eastern DRC, with a planned 50,000 people to be vaccinated in Goma. |

| November 27-28, 2019: WHO and other organizations temporarily halt operations and evacuate some staff after armed militia groups kill four people at Ebola response centers and violent protests erupt. |

| NOTES: WHO means World Health Organization. The DRC means the Democratic Republic of the Congo. |

How many cases and deaths have there been in the DRC?

As of December 16, 2019, the DRC Ministry of Health reports the country has had 3,348 cases (see figure below), of which there were 2,210 deaths. The number of new cases reported each week has declined noticeably since the end of July 2019, indicating progress has been made in interrupting transmission. Still, cases continue to occur, and recent violence in some Ebola-affected areas has interrupted the response, sparking concerns about this potentially leading to an increase in Ebola cases. Regardless, response activities could be needed for another several months at least, and another increase in transmission remains a concern. The crude case fatality ratio for this outbreak is high, at 66%, as of December 16, 2019.

Health care workers (HCWs), such as nurses and doctors, caring for Ebola patients have been at particularly high risk of infection. At least 169 cases (about 5% of total cases) over the course of this outbreak have occurred among HCWs. This Ebola outbreak has also disproportionately affected children, with about 15 percent of all cases occurring among children under 5 and a higher proportion of the child cases dying from the disease compared with older age groups.

What are the key factors driving the outbreak in the DRC?

Multiple issues make responding to this Ebola outbreak more challenging than any prior outbreaks in the DRC. These include:

- ongoing violence from armed groups that is impeding the response efforts, including violence against Ebola responders, amid long-standing conflict;

- mistrust of the DRC government and outsiders, including Ebola responders, in affected communities;

- disbelief in Ebola (studies find that many in the affected areas believe the Ebola outbreak is not real but rather a hoax perpetrated by the government or other outside parties);

- a shortfall in funding for the Ebola response efforts in the DRC, despite increasing calls from the World Health Organization for donors to fill the gap; and

- transitions in the leadership of the DRC government, including transitions in oversight of the Ebola response.

This combination of factors has made responding to this outbreak a much more difficult challenge compared with previous outbreaks in the DRC (see KFF brief).

Role of the U.S.

U.S. engagement in the current outbreak has been limited compared to its role in the 2014-2015 West Africa Ebola outbreak response, where the U.S. played a major leadership role, mobilizing an unprecedented amount of funding, other resources, and personnel to support the Ebola response. Since then, there have been improvements in the global capacity to respond to Ebola, particularly on the part of WHO, and the DRC has had significant experience in addressing prior Ebola outbreaks; both WHO and the DRC took the lead early on in the current outbreak (see KFF brief). In addition, insecurity in the affected areas of the DRC has prevented U.S. agencies from being more involved, as U.S. personnel have been mostly restricted from working directly in the hardest hit areas due to safety concerns. However, the U.S. has provided significant funding and technical assistance in the DRC and in neighboring countries, working in conjunction with national governments, United Nations (U.N.) agencies, and other organizations leading the response. In fact, the U.S. is the largest donor to the Ebola response effort in the country, having provided over $250 million since August 2018.

While the number of Ebola cases in the DRC continues to decline from a peak over the summer, major challenges remain for the U.S. and other responders, such as: completing the task of interrupting transmission even amid ongoing violence, preventing expansion of the outbreak into other geographic areas, and effectively transitioning from an emergency response to a longer-term development effort to help stabilize and build up health systems in the affected areas.

What U.S. agencies are involved in the response?

The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) are the two main agencies contributing to the U.S. government response. USAID’s Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA) coordinates U.S. emergency response efforts in the DRC, and in September 2018, the agency deployed a Disaster Assistance Response Team (DART) to the DRC in response to the outbreak. USAID’s Bureau for Global Health provides operational and personnel support. Several CDC offices, including the Center for Global Health’s Division of Global Health Protection and the National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases’ Division of High-Consequence Pathogens and Pathology (NCEZID/DHCPP), provide technical and personnel support. CDC efforts in the DRC are coordinated through its Emergency Operations Center (EOC) in Atlanta, which was activated in June 2019 at its lowest level (level 3).

Other U.S. agencies engaged in Ebola efforts include the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (conducting research on drug and vaccine development, including Ebola treatment trials in the DRC); the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (regulating drug and vaccine development); and the Department of State (coordinating the U.S. and international diplomatic response).

Are U.S. government personnel working in the outbreak areas in the DRC?

U.S. personnel have been assisting in the DRC since the outbreak was announced in August 2018, but since late August/early September 2018, no U.S. personnel have been allowed to directly engage in response activities in active transmission areas in northeastern DRC. Citing safety concerns due to ongoing violence there, U.S. officials have decided to keep CDC and other U.S. staff away from the front lines of the response. Outside experts have made calls for the U.S. to return CDC staff to affected areas to assist more directly. So far though, there is little indication that the U.S. government will deviate from its current policy, though CDC reports working with the U.S. Department of State to “pre-position CDC staff in Goma to rapidly respond to hotspots where the security situation is permissible.”

Outside of the outbreak zone, U.S. personnel continue to assist. The DART – a “team of disaster and health experts” from USAID and CDC – continues its work in the DRC in response to the outbreak. CDC reports 34 staff working the DRC. Other CDC workers have deployed to WHO headquarters and to neighboring countries, such as Uganda, to assist in keeping the virus from crossing borders and to support countries in preparedness and response activities.

How much funding has the U.S. provided?

USAID reports providing about $266 million toward the Ebola response in the DRC and surrounding countries since the outbreak began in August 2018. Of this amount, $252 million is for activities in the DRC, while $14 million is for preparedness and response activities in Burundi, Rwanda, South Sudan, and Uganda. No estimate is available for the amount that CDC has spent on its Ebola response activities, though WHO reports the CDC has provided $500 thousand in funding to its efforts. The funding for both USAID and CDC, as well as for other U.S. agencies, in the response is not new funding; rather, it has been drawn from unspent FY 2015 emergency Ebola supplemental appropriations provided by Congress at the time of the West Africa Ebola outbreak. For USAID, leftover funding in the International Disaster Assistance (IDA) account that was designated for “assistance for countries affected by, or at risk of being affected by,” Ebola is being utilized for this purpose, and for CDC, leftover funding that was designated for Ebola international preparedness and response is being utilized. CDC’s leftover funding expired at the end of FY 2019 on Sept. 30, 2019 and, per communication with CDC, was expected to have been entirely spent by that time. In recent months, Congress has stated that CDC may use existing funds in the Infectious Diseases Rapid Response Reserve Fund, which was established in FY 2019, for CDC Ebola response.

Global Response Activities

Who leads the response to the outbreak?

The DRC government, including the Ministry of Health, and agencies of the U.N. lead the outbreak response. WHO is the lead U.N. agency for the public health response; other key U.N. actors include the U.N. Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), the U.N. Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the World Food Programme (WFP), and MONUSCO, a multinational peacekeeping force that has been assisting with security. U.N. actors are led by a U.N. Emergency Ebola Response Coordinator.

Other key actors in and supporters of the response include governments of various countries, including the U.S.; multilateral organizations, such as the World Bank and Gavi; international and national non-governmental organizations (NGOs), such as Medicins Sans Frontieres (MSF), International Medical Corps, the Alliance for International Medical Action (ALIMA), and the International Red Cross/Red Crescent; and other partners.

What is the plan for ending the outbreak in the DRC?

Current public health response efforts in the DRC are focused on interrupting chains of Ebola transmission through identifying, isolating, and caring for cases before they transmit the disease further. The goal of the response is to bring the number of cases down “to zero”. Ebola outbreaks are usually declared to be over after 42 days have passed since the last known case (equal to two incubation periods of Ebola virus disease). A national Strategic Response Plan outlines the overall strategy, objectives, and priority activities for responding to the outbreak. There have been four iterations of the plan to date, each covering a specific period of time. The current plan that focuses on the core public health “pillar” of the response covers planned activities from July through the end of December 2019. It addresses strengthening response capacities in priority areas such as: coordination, surveillance and laboratory capabilities, infection prevention and control measures, vaccination, human resources, security, and risk communication among others. Complementary humanitarian response activities are another “pillar” of the response and outlined in a broader integrated Ebola response strategy, which includes efforts addressing food assistance, employment, and economic development in Ebola-affected regions.

Has the outbreak been declared a global emergency?

On July 17, 2019, the WHO Director-General accepted the recommendation of the Emergency Committee and declared the DRC Ebola outbreak to be a “public health emergency of international concern” (PHEIC). A PHEIC is “an extraordinary event which is determined to constitute a public health risk to other States through the international spread of disease and to potentially require a coordinated international response.” In its declaration, WHO released a set of recommend actions for affected countries, neighboring countries, and all states. This was the fourth time the Emergency Committee had met to discuss a potential PHEIC declaration for Ebola in the DRC; each of the prior three times the Committee recommended not to do so.

At its most recent meeting, on October 17, 2019, the WHO Emergency Committee again recommended that the PHEIC declaration remain in place.

What has been the role of vaccination in the current outbreak?

Vaccination has been an important component of the response since it began. This outbreak marks the first time that an effective vaccine is available and being used as a core component of an Ebola response. Authorities have mostly used a “ring vaccination” approach, targeting vaccination of those who have been in contact with a case of Ebola and the contacts of those contacts, as well as other groups at potential risk of exposure such as health care workers. As of December 8, 2019, over 256,000 people have been vaccinated in the DRC since the start of the outbreak, which has likely prevented hundreds, if not thousands, of Ebola cases already. Authorities have been primarily using a vaccine manufactured by Merck, which the company has provided free of charge to WHO and the DRC for the purposes of the response. The Merck vaccine, which was being deployed on an emergency use basis under a “compassionate use” protocol, received approval from European regulators and prequalification from WHO in November 2019, making it the first officially licensed Ebola vaccine. It is not yet approved and licensed by the FDA (though it is under review and an FDA regulatory decision is expected in early 2020). Costs for vaccine distribution and management of vaccinations in the response are shared among Gavi, WHO, other donors, and the DRC government.

In addition to the vaccination efforts in the DRC, neighboring countries are also vaccinating certain people, such as health workers, in areas at risk of seeing or that have seen Ebola cases due to cross-border spread (like Uganda, with at least 5,000 people vaccinated thus far).

A second Ebola vaccine, manufactured by Johnson & Johnson, is also available. Following recommendations from WHO and other expert groups, the DRC government decided to introduce the second vaccine into some at-risk areas of the country that do not have active Ebola transmission. For example, DRC authorities began vaccinating 50,000 people in Goma with the second vaccine in November 2019, and in December 2019, the DRC and neighboring Rwanda initiated a new vaccination campaign using that vaccine to protect people in at-risk areas on their mutual border.

Is there an adequate supply of vaccine?

It appears there are enough doses of the Merck vaccine to meet the demands of the current WHO/DRC government’s ring vaccination approach. Currently there are enough vaccine doses to vaccinate 300,000 people, which is greater than the total number of people vaccinated in the outbreak over the first 17 months of the response. In addition, WHO reports that Merck will produce enough vaccine over the next 6 to 18 months to vaccinate an additional 1.3 million people. Gavi announced in December 2019 that it will support a new global stockpile of 500,000 doses of Ebola vaccine, to be made available for emergency use as needed.

There is reportedly an adequate supply of the second (Johnson & Johnson) Ebola vaccine, with enough to vaccinate approximately 2 million people.

Are treatments available for those infected with Ebola?

There are no FDA- or other approved treatments for Ebola, though several promising treatments are under development. Four experimental treatments have been studied in a clinical trial among Ebola patients in the DRC, and in August, the U.S. NIH announced that initial results of the trial indicated two of those treatments (the monoclonal antibody mAb114 and the multi-antibody “cocktail” REGN-EB3) showed the most promise. Ebola patients in the DRC enrolled in the trials are offered these two treatments as investigators further evaluate them. The treatments are still under investigation and being offered on a “compassionate use” basis only in the DRC.

What has the response cost, and how much funding has been provided?

From August 2018 through early December 2019 the amount of funding directed to response activities in the DRC included under four iterations of a national Strategic Response Plan has reached $361 million. This amount does not include additional DRC outbreak activities not captured under the plans, nor response costs in Uganda and preparedness costs in neighboring countries.

Funding amounts provided under each of the plans so far:

- August – October 2018: DRC government data show that the first plan was fully funded, with $44.2 million made available to meet the $43.8 million requested for the August to October 2018 period the plan covered.

- November 2018 – January 2019: U.N. data shows that the second plan was fully funded, with donors (largely the World Bank) providing $61.4 million (including some funds leftover from the first phase of the response) of the $61.3 million requested to cover the period through January 2019.

- February – July 2019: U.N. data shows the third plan has received $109.3 million from February through July 2019, of the $147.9 million requested to cover the period through July 2019. This includes $40 million from the World Bank, with more promised, and $31.2 million from USAID.

- July – December 2019: WHO data shows the current plan has received at least $148.3 million from August through early December 2019, of the $287.6 million requested for the public health pillar of the response through December (U.N. data tracking donor funding toward the current plan is not yet available, but WHO is reporting the funding it has received under the plan). The plan has substantially higher funding needs than prior iterations. The broader response strategy, which includes the funding requirements of the public health pillar within its funding assessment, is requesting more than $500 million for the broader DRC response through December; some donors, including the World Bank, United Kingdom, and the European Union, have already announced they will be providing additional funding for the response.

As mentioned earlier, USAID reports providing about $252 million toward the Ebola response in the DRC and about $14 million for activities in neighboring countries since the outbreak began in August 2018 (this includes funding channeled through the DRC national plans as well as funding not captured under the plans). No estimate is available for the amount that CDC has spent on its Ebola response activities, though WHO reports the CDC has provided $500 thousand in funding to its efforts. All U.S. funding for the current outbreak is drawn from existing funding sources (i.e., no new funding has been appropriated to agencies by Congress for this Ebola response, thus far).

See the KFF data note on donor funding for the response for further information.

Key Issues Going Forward

Now well into its second year, the Ebola outbreak in the DRC remains challenging for responders, despite having important tools (such as vaccines and new treatment options) on hand. This is because the underlying factors driving transmission of Ebola in the DRC remain. The security situation shows no sign of abating, and there is a fear that it can always worsen. Mistrust of public health authorities also remains a barrier to response efforts. While it is not possible to predict the trajectory of the outbreak, it could take at least a few more months to fully contain even under good circumstances, so given the complex set of challenges being faced, the outbreak could take even longer than that to be brought under control.

Addressing these longstanding challenges more effectively is the aim of the broader integrated response strategy being implemented in the DRC. This strategy, which includes the public health pillar’s current national plan and is designed to guide the response through the end of December 2019, calls for greater community engagement, support for health and development interventions beyond addressing Ebola alone, a new approach to security, and more coordination among all responders.

Finally, the major questions for the U.S. government going forward include: whether or not it will change its approach and engagement in the DRC to allow U.S. government personnel to directly engage in public health activities on the frontlines of the response, how the U.S. will contribute to finally breaking all chains of transmission, and how the U.S. will support efforts to transition from an emergency response to a longer-term strategy for supporting the health care system in the affected areas to help prevent and contain any future recurrences of Ebola or other outbreaks.

Additional Resources

- DRC Ministry of Health – WHO AFRO Ebola in DRC dashboard

- DRC Multisectoral Committee on Ebola Response (CMRE) daily situation reports (from Aug. 3, 2019)

- DRC Ministry of Health daily situation reports (prior to Aug. 3, 2019)

- WHO DRC Ebola situation reports (earlier reports)

- WHO Ebola disease outbreak news

- USAID DRC Crisis webpage

- CDC Ebola Outbreak in the DRC webpage

- KFF infographic Ebola: 5 Key Questions

- KFF Ebola materials