The Landscape of Medicare and Medicaid Coverage Arrangements for Dual-Eligible Individuals Across States

This brief was updated on October 24, 2024 to incorporate updates to Medicare and Medicaid administrative data.

Policymakers, researchers, and others have long called for reforms to improve the coordination of Medicare and Medicaid benefits for the people who receive health insurance coverage through both programs. People in this group, also known as dual-eligible individuals, have lower incomes, are more racially and ethnically diverse, and often face greater mental and physical health challenges than the general Medicare population. Dual-eligible individuals with full Medicaid benefits, who comprise most dual-eligible individuals, usually have Medicare benefits covered under traditional Medicare or Medicare Advantage and, separately, Medicaid benefits covered through Medicaid fee-for-service or Medicaid managed care (referred to here as Medicaid delivery systems). A small percentage of dual-eligible individuals have most of their Medicare and Medicaid benefits covered through a single plan or program.

Some have raised concerns that, for dual-eligible individuals, care is fragmented, and benefits are poorly coordinated across the Medicare and Medicaid programs, contributing to lower quality care and higher costs. There are concerns that separate coverage arrangements make it more difficult for dual-eligible individuals to navigate different coverage rules and provider networks. Over the years, there have been numerous efforts to increase the integration of benefits and financing for the dual-eligible population across the two programs, including the Financial Alignment Initiative authorized under the Affordable Care Act. A recent systematic review of arrangements that aim to integrate benefits and financing for the dual-eligible population found that evidence on care coordination and hospitalizations is inconclusive; health outcomes are mixed and vary by type of arrangement; and some arrangements are found to increase Medicare spending. These findings are consistent with a previous inventory of evaluations by the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC), raising questions about how well this approach serves dual-eligible individuals or achieves savings.

There are several proposals in the current Congress to integrate coverage by enrolling all dual-eligible individuals in a single plan or program that provides both Medicare and Medicaid benefits, as well as additional funding and changes to financing for states that pursue integrated models of coverage. These proposals raise a number of questions for consideration, including how to establish integrated plans in places without health plans experienced in providing Medicare and Medicaid benefits; how to minimize potential disruptions to existing care relationships; how to establish fair Medicare and Medicaid payments to the entities responsible for services; whether to provide dual-eligible individuals the option to get benefits under traditional Medicare, which does not have a limited network of providers; and to the extent private insurers administer these arrangements, how best to hold them accountable for improving care and lowering costs.

This analysis uses merged beneficiary-level Medicare and Medicaid data from 2021 – based on the most current final version of Medicaid data at the time of this analysis — to document sources of coverage for dual-eligible individuals nationwide and by state, which provides data useful for assessing the implications of potential proposals to change coverage arrangements for this population. The analysis includes 7.9 million dual-eligible individuals living in 47 states and the District of Columbia, who had full Medicaid benefits in March 2021 (referred to simply as dual-eligible individuals hereafter; see methods for further details).

Key Takeaways

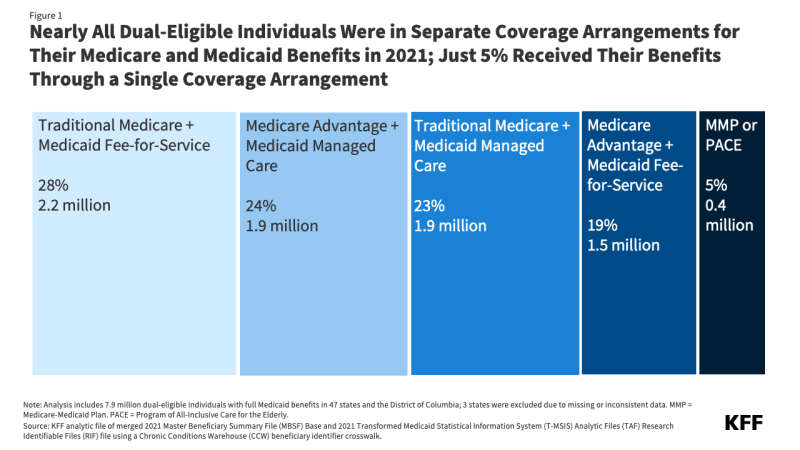

- The vast majority (94%) of full-benefit dual-eligible individuals received their Medicare and Medicaid benefits through separate Medicare and Medicaid coverage arrangements in 2021.

- 28% of dual-eligible individuals were in traditional Medicare and Medicaid fee-for-service;

- 23% were in traditional Medicare and Medicaid managed care; and

- 19% in Medicare Advantage and Medicaid fee-for-service.

- 24% were in Medicare Advantage and Medicaid managed care;

- Just 5% of dual-eligible individuals received their Medicare and Medicaid benefits through a single coverage arrangement, either the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) or a Medicare-Medicaid Plan (MMP).

- Medicare and Medicaid coverage combinations for dual-eligible individuals varied widely across states. For example, in 18 states and DC, more than half of all dual-eligible individuals were in traditional Medicare and Medicaid fee-for-service, while in 4 states, more than half of all dual-eligible individuals were in Medicare Advantage and Medicaid managed care. Rhode Island and Ohio were the only states that had more than 25% of their dual eligible population in PACE or a Medicare-Medicaid Plan, while in 38 states and DC, fewer than 5% of the dual-eligible individuals were in these plans, in many cases, because they were not available.

- Within Medicaid coverage arrangements, 55% of dual-eligible individuals were enrolled in multiple Medicaid delivery systems, which refers to the way a state Medicaid program provides benefits to enrollees. This occurs because states may offer limited benefit plans covering only a subset of Medicaid benefits, such as behavioral health or dental care, and they may exclude a subset of benefits from a larger managed care contract.

- Within Medicare coverage arrangements:

- 28% of dual-eligible individuals received their Medicare benefits through a Medicare Advantage dual eligible special needs plan (D-SNP), though relatively few were enrolled in fully-integrated dual eligible special needs plans (FIDE SNPs), which generally offer a greater degree of coordination between Medicare and Medicaid than other types of D-SNPs.

- 12% of dual-eligible individuals were in traditional Medicare and aligned with a Medicare Shared Savings Program Accountable Care Organization (ACO), in which groups of doctors, hospitals and other health care providers form partnerships to collaborate and share accountability for the quality, coordination, and cost of care delivered to their patients.

How Did Dual-Eligible Individuals Receive Their Medicare and Medicaid Benefits in 2021?

Most (95%) dual-eligible individuals received Medicare and Medicaid benefits through separate coverage arrangements.

Existing coverage arrangements for dual-eligible individuals vary in how benefits are coordinated, and how plans and providers are paid. In all cases, Medicare serves as the primary payer and source of coverage, covering acute and post-acute care, while Medicaid pays Medicare premiums, and in most cases, cost-sharing. Full-benefit dual-eligible individuals are also eligible for Medicaid benefits that are not covered by Medicare, such as long-term care, vision, and dental benefits.

The most common coverage combination was traditional Medicare and Medicaid fee-for-service, accounting for 28% of dual-eligible individuals (Figure 1). In traditional Medicare and Medicaid fee-for-service, a mix of fee-for-service, bundled and prospective payments, as well as value-based payment models, such as accountable care organizations (ACOs), are used. In traditional Medicare, dual-eligible individuals may seek care from any provider that accepts Medicare (only a small share of providers opt out), with minimal constraints on health care use (such as prior authorization). However, in most states, there are policies that limit Medicaid payment of Medicare cost sharing so that total payment does not exceed the Medicaid rate, which is typically lower than the Medicare rate. This means providers in these states may be paid less to treat dual-eligible individuals than to treat other Medicare beneficiaries. Research shows that in those states, dual-eligible individuals have fewer primary care visits, suggesting that Medicare providers may be less willing to see dual-eligible individuals when they are paid less. For Medicaid covered services, dual-eligible individuals with Medicaid fee-for-service can see all providers that accept Medicaid in the state.

About one-quarter (24%) of dual-eligible individuals were in Medicare Advantage and Medicaid managed care. With this coverage combination, Medicare benefits are provided by Medicare Advantage plans and Medicaid benefits are provided by health plans that contract with state Medicaid programs. These entities receive set payments per enrollee, adjusted for health status, to incentivize care coordination. Plans can establish provider networks and use other tools to manage service utilization, including prior authorization.

About one-quarter (23%) of dual-eligible individuals were in traditional Medicare and Medicaid managed care. With this coverage combination, Medicare benefits are provided under traditional Medicare and Medicaid benefits are provided by health plans. Dual-eligible individuals can go to any provider that accepts dual-eligible individuals but may have to see a provider that is in network for Medicaid-covered services.

Just under one in five (19%) dual-eligible individuals were in Medicare Advantage and Medicaid fee-for-service. With this coverage combination, Medicare benefits are provided by Medicare Advantage plans and state Medicaid programs administer Medicaid benefits.

A small share (5%) of dual-eligible individuals were enrolled in a single plan or program that covered their Medicare and Medicaid benefits.

Medicare-Medicaid Plans and PACE are two models of coverage for dual-eligible individuals that provide Medicare and Medicaid benefits, including long-term services and supports, behavioral health services, and prescription drug coverage, under a single plan or program with integrated financing. Medicare-Medicaid Plans and PACE are not available in all areas, which helps to explain the relatively low enrollment in these coverage arrangements. Medicare-Medicaid Plans are a single plan that provide most Medicare and Medicaid benefits and were established as a demonstration under the Financial Alignment Initiative. They were offered in 9 states in 2021. PACE, a program that provides comprehensive medical and social services, was offered in a subset of counties across 31 states in 2021 (Appendix Table 1).

Evaluations of Medicare-Medicaid Plans and PACE have shown varied outcomes. Most evaluations of Medicare-Medicaid Plans found few measurable differences in health outcomes or spending. Many evaluations of PACE found improved outcomes, such as lower mortality and depression, but there is limited evidence on how the program affects Medicare and Medicaid spending.

Medicare and Medicaid coverage combinations for dual-eligible individuals varied widely across states.

In all states included in this analysis, most dual-eligible individuals received their Medicare and Medicaid benefits from separate coverage arrangements, though the distribution of the coverage combinations varied widely (Figure 2). (Note, Alabama, Arkansas, and Idaho were excluded from the below analysis due to missing or inconsistent data.)

- The share of dual-eligible individuals in traditional Medicare and Medicaid fee-for-service (28% nationally) ranged from less than 1% in Tennessee, Nebraska, and Hawaii to over 50% in 18 states and DC.

- The share of dual-eligible individuals in Medicare Advantage and Medicaid managed care (24% nationally) ranged from less than 1% in 18 states and DC to over 50% in Arizona, Hawaii, Pennsylvania, and Tennessee.

- The share of dual-eligible individuals in traditional Medicare and Medicaid managed care (23% nationally) ranged from less than 1% in 19 states to over 50% in 6 states (Delaware, Iowa, Kansas, Nebraska, New Hampshire, and New Jersey).

- The share of dual-eligible individuals in Medicare Advantage and Medicaid fee-for-service (19% nationally) ranged from less than 1% in Alaska, Hawaii, Iowa, Nebraska, and Tennessee to 52% in South Carolina and 54% in Georgia.

- The share of dual-eligible individuals enrolled in a single coverage arrangement – Medicare-Medicaid Plans or PACE – (5% nationally) ranged from less than 1% in 32 states and DC to 28% in Ohio and 34% in Rhode Island. In 18 (including DC) of the 32 states and DC with low Medicare-Medicaid Plan and PACE enrollment, neither Medicare-Medicaid Plans nor PACE were available in any county.

Some states have worked to expand access to PACE in different areas and legislation has been proposed requiring all states to offer this program. The challenges in expanding PACE include high start-up costs, administrative barriers in reviewing applications for new programs and service area expansions, and limitations on federal and state resources.

In 20 states and DC, at least 80% of dual-eligible individuals were enrolled in Medicaid fee-for-service and in 14 states, at least 80% were enrolled in Medicaid managed care (Appendix Table 2). In the remaining 13 states, enrollment in Medicaid fee-for-service and managed care was more mixed. The tendency for most enrollees to be in either Medicaid managed care or fee-for-service within a given state reflects state decisions about whether to provide Medicaid benefits through managed care for dual-eligible individuals, and if so, whether enrollment is mandatory or voluntary. Among the states included in this analysis, 8 states did not enroll dual-eligible individuals in Medicaid managed care in 2021.

In 7 states, at least 80% of dual-eligible individuals were in traditional Medicare, and there were no states where at least 80% of dual-eligible individuals were enrolled in Medicare Advantage (Appendix Table 3). (Medicare Advantage enrollment is higher in Puerto Rico, which is not included in this analysis). The pattern of Medicare coverage for dual-eligible individuals is in part due to differences within states with respect to Medicare Advantage penetration. While some, mostly rural, states have low Medicare Advantage enrollment across the state, in most other states, Medicare Advantage penetration varies substantially across counties within the state. Counties with higher Medicare Advantage penetration and larger numbers of beneficiaries have the effect of boosting the state’s overall Medicare Advantage enrollment rate.

More than half of dual-eligible individuals were enrolled in multiple Medicaid delivery systems.

Within Medicaid, the way a state Medicaid program provides benefits to enrollees is sometimes referred to as a delivery system. State Medicaid programs may provide benefits on a fee-for-service basis, in which states reimburse health care providers a payment for each service, or through managed care, in which Medicaid pays a predetermined fee to another entity to deliver a specified set of benefits. Sometimes the set of benefits includes all Medicaid-covered services, but other times it is limited to a subset of benefits such as behavioral health, dental care, or long-term services and supports. As a result, enrollees in managed care may receive some services through the fee-for-service system or through limited benefit plans or carve-out plans that cover a small number of Medicaid benefits. Similarly, enrollees in Medicaid fee-for-service may receive a subset of their benefits through a limited benefit plan. To better understand how many delivery systems dual-eligible individuals enrolled in, this analysis counted the number of managed care plans each person was enrolled in and, for enrollees in managed care, used the claims data to determine whether they also received services through fee-for-service Medicaid (see methods).

More than half (55%) of dual-eligible individuals were enrolled in multiple Medicaid delivery systems (Figure 3). Nearly half of dual-eligible individuals (46%) were enrolled in two Medicaid delivery systems, 9% were enrolled in three or more, and 45% were enrolled in one. The extent to which dual-eligible individuals were enrolled in multiple Medicaid delivery systems varied substantially across states from less than 1% in 9 states to over 97% in Iowa, New Jersey, and Nebraska (Appendix Table 4). Variation across states reflects differences in the extent to which states use limited benefit plans and the extent to which states that use managed care exclude some services from the managed care contracts, instead providing them through fee-for-service or limited benefit plans.

Dual-eligible individuals in Medicaid managed care or single coverage arrangements were enrolled in multiple Medicaid delivery systems more often than those in Medicaid fee-for-service. Most dual-eligible individuals enrolled in Medicaid managed care (71%) were enrolled in more than one delivery system, as were most dual-eligible individuals in a Medicare-Medicaid Plan or PACE (60%). Fewer than half (39%) of dual-eligible individuals in Medicaid fee-for-service were enrolled in multiple service delivery systems. The large share of dual-eligible individuals in single coverage arrangements with multiple Medicaid delivery systems is primarily because Medicare-Medicaid plans may exclude some services from their contracts, such as hospice and certain behavioral health services (though the plan is still responsible for coordinating these services for enrollees). In contrast, PACE always provide long-term care benefits and are intended to be the sole source of all other Medicaid and Medicare benefits. As a result, two thirds (65%) of Medicare-Medicaid plan enrollees were enrolled in multiple Medicaid delivery systems compared with only 15% of those in PACE (data not shown).

States’ use of limited benefit plans and exclusions from managed care contracts may allow for management of specialized Medicaid benefits but means that single coverage arrangements may still not be fully integrated. One of the primary reasons states may exclude some benefits from a primary delivery system is when the primary delivery system lacks experience in delivering specialized Medicaid benefits such as long-term care, behavioral health, or non-emergency medical transportation. In some cases, the entities with the most experience providing such benefits are standalone limited benefit plans, which frequently include county departments of social or behavioral health services. In other cases, the state is the most experienced with providing such benefits, so they are excluded from the managed care contracts that cover other Medicaid benefits. There are tradeoffs between fully integrating Medicare and Medicaid benefits through a managed care plan and allowing the most experienced entities to provide specialized benefits.

More than half of all dual-eligible individuals enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans were enrolled in D-SNPs

Among the 43% of dual-eligible individuals in Medicare Advantage, more than half (28%) were covered through dual eligible special needs plans D-SNPs (including 24% in coordination-only D-SNPs or highly integrated dual eligible special needs plans (HIDE SNPs)), and 3% in fully integrated dual eligible special needs plans (FIDE SNPs) (Appendix Table 1). D-SNPs are required to coordinate Medicare and Medicaid benefits to different degrees depending on the state in which they operated and the type of D-SNP, but those with the highest degree of coordination, FIDE SNPs, have the lowest enrollment.

There are efforts underway intended to improve how dual-eligible individuals in Medicare Advantage SNPs receive their Medicare and Medicaid benefits. In 2021, FIDE SNPs were required to provide all Medicare and some Medicaid benefits, including LTSS or behavioral health (but not required to provide both), under the same parent organization (from the D-SNP or an aligned Medicaid managed care plan owned by the D-SNP’s parent company). Additionally, states determined whether to require exclusively aligned enrollment, meaning the plans could only enroll dual-eligible individuals who received their Medicare and Medicaid benefits from the same parent organization (an option that four states – Idaho, Massachusetts, Minnesota, and New Jersey exercised).

Starting in 2025, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) will require FIDE SNPs to have exclusively aligned enrollment. Consequently, FIDE SNPs will not be able to enroll dual-eligible individuals unless they are enrolled in the aligned Medicaid plan (further details in Table 1). Additionally, the FIDE SNP or its aligned Medicaid plan will be required to cover a more comprehensive set of services, including LTSS, behavioral health, and home health. Although Medicare and nearly all Medicaid benefits will be provided by a single parent organization, financing will remain separate (see Table 1 for further details).

About one in eight (14%) dual-eligible individuals were in individual Medicare Advantage plans and the remaining 2% were in chronic condition or institutional SNPs. Individual Medicare Advantage plans are open to all Medicare beneficiaries. Chronic condition SNPs (C-SNPs) serve individuals with specific chronic conditions, while institutional SNPs (I-SNPs) serve individuals who are in institutions or receiving long term services and support in the community. While C-SNPs and I-SNPs enroll dual-eligible individuals, they are not required to coordinate Medicare and Medicaid benefits.

Just over half (52%) of dual-eligible individuals were in traditional Medicare and most were not aligned to an accountable care organization.

The Affordable Care Act created the Medicare Shared Savings Program, which permanently established accountable care organizations (MSSP ACOs) as part of the Medicare program. ACOs are a group of doctors, hospitals, and other health care providers that form partnerships to coordinate care for their patients. CMS attributes traditional Medicare beneficiaries to an ACO if they received most of their primary care services from a provider affiliated with the ACO. Beneficiaries also have the option of voluntarily aligning with an ACO. Providers that participate in a Medicare ACO are required to inform their patients of their participation. In addition to the MSSP ACOs, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation has tested various other ACO models over the years. This analysis focused on MSSP ACOs and thus may undercount the number of dual-eligible individuals aligned to any Medicare ACO in 2021.

Most dual-eligible individuals in traditional Medicare were not aligned to MSSP ACOs. Overall, just 12% of dual-eligible individuals were in traditional Medicare and aligned to an MSSP ACO (Figure 4). Across all states, at least some dual-eligible individuals were aligned with a MSSP ACO (Appendix Table 1). The share of dual-eligible individuals in traditional Medicare aligned to a MSSP ACO ranged from just under 1% in Vermont to 30% in Delaware.

CMS aims to have all traditional Medicare beneficiaries, including dual-eligible individuals, in alternative payment models, which to date are predominately ACOs, by 2030. Given the higher share of dual-eligible individuals in traditional Medicare and the relatively low number aligned to MSSP ACOs, this move could have broad implications for dual-eligible individuals who remain in traditional Medicare and raises questions about how ACOs will help dual-eligible individuals access and coordinate their Medicare and Medicaid benefits. In the 2023 final rule, CMS made changes to the Medicare Shared Savings Program, including rewarding ACOs that provide quality care to dual-eligible individuals and other underserved populations. In addition, new ACO models are being tested, in particular the ACO REACH Model, which aims to align underserved communities, including dual-eligible individuals, with accountable care arrangements that are specifically designed to meet their needs. More evaluation will be useful in understanding how well these goals are achieved.

This work was supported in part by Arnold Ventures. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities.

Methods |

| Data: Data are from a KFF analytic file that merged the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse 2021 research-identifiable Master Beneficiary Summary File (MBSF) Base and the 2021 Transformed Medicaid Statistical Information System (T-MSIS) Analytic Files (TAF) Research Identifiable Files (RIF) file using a Chronic Conditions Warehouse (CCW) beneficiary identifier crosswalk.

Dual-eligible individual inclusion criteria: Full dual-eligible individuals were included if (1) they were in both the MBSF and T-MSIS files using the CCW crosswalk (2) and if individuals were a full dual-eligible individual in March (03) 2021 using the Medicare monthly DUAL_STUS_CD_03 with values of 02,04,08 or the Medicaid monthly code (March=03) DUAL_ELGBL_CD_03 with values of 02,04,08 or the monthly code (March=03) RSTRCTD_BNFTS_CD_03 values of 1,A,D,4,5,7. Dual-eligible individuals also had to have both Part A and B in March 2021 to be included in this analysis. State inclusion criteria: To assess the usability of states’ data, the analysis examined quality assessments from the DQ Atlas for enrollment in managed care and compared enrollment in comprehensive managed care with the Medicaid Managed care enrollment report for dual-eligible individuals in 2021. The analysis excluded any states that had both a “Unclassified/ Unusable” DQ Atlas assessment and more than 50% difference between the number of dual-eligible individuals in managed care in T-MSIS and the number reported in the Medicaid managed care enrollment report. Three states (Alabama, Arkansas, and Idaho) were excluded based on these criteria in 2021, leaving 47 states and DC in the main analysis. Enrollees were assigned a state based on their T-MSIS STATE_CD. Assignment to Medicare coverage arrangements Traditional Medicare: Beneficiaries without a valid Medicare Advantage contract ID in March 2021 were defined as enrolled in traditional Medicare. This analysis identifies individuals who are in traditional Medicare and aligned to an Accountable Care Organization using the Medicare Shared Savings Program Accountable Care Organizations (ACO) Beneficiary-level RIF. Dual-eligible individuals were identified as being aligned to an ACO if they were assigned to an ACO in quarter 1 (Q1_Assign). Medicare Advantage plans: Beneficiaries with a valid contract ID in March 2021 were identified as enrolled in Medicare Advantage. To determine the type of plan in which the beneficiary was enrolled, the contract ID and plan ID were matched to the March 2021 Monthly Enrollment by Plan, or the Special Needs Plan Report data published by CMS. This includes enrollment in all private plans which are predominately Medicare Advantage plans. Program Of All-Inclusive Care for The Elderly (PACE) or Medicare-Medicaid Plan. Enrollment in PACE and Medicare-Medicaid Plan was determined using the approach defined in the “Medicare Advantage” section. Assignment to Medicaid delivery systems PACE or Medicare-Medicaid Plan. Enrollment in PACE and Medicare-Medicaid Plan for the Medicaid delivery systems was determined using Medicare data and the approach is defined in the “Medicare Advantage” section. Medicaid managed care. For enrollees who were not enrolled in PACE or a Medicare-Medicaid Plan, enrollment in comprehensive managed care plans was identified by the MC_PLAN_TYPE_CD_03 variable with values of 01 (Comprehensive managed care), 04 (Health Insuring Organization), 07 (Long-term Care Prepaid Inpatient Health Plan (PIHP)), 17 (PACE), 19 (Long term care services and supports and mental health Prepaid Inpatient Health Plan(PIHP)), 80 (Integrated care for dual-eligible individuals). Enrollment data among dual-eligible individuals using the values of PACE (17) and Integrated care for dual-eligible individuals (80) were not always consistent with the MBSF (which was used to assign PACE and Medicare-Medicaid Plan status). As a result, dual-eligible individuals with a value or 17 or 80 who did not have a corresponding assignment in the MBSF were assigned to Medicaid managed care. Medicaid fee-for-service. Enrollment in Medicaid fee-for-service includes anyone not in PACE, a Medicare-Medicaid Plan, or Medicaid managed care, as defined above. This analysis does not identify individuals who receive their Medicaid benefits through a Financial Alignment Initiative managed FFS program. Number of Medicaid delivery systems. The analysis counted the number of Medicaid delivery systems by adding the number of plan types identified in MC_PLAN_TYPE_CD_03. All plan types were included except for 02 (Traditional Primary Care Case Management provider arrangement), 03 (Enhanced Primary Care Case Management provider arrangement), 60 (ACO), 70 (Health/Medical Home). For individuals enrolled in managed care, the analysis counted fee-for-service Medicaid as an additional delivery system if individuals incurred any fee-for-service spending in 2021. |