How Might Current Federal Drug Pricing Proposals Impact Medicaid?

Rachel Dolan

Published:

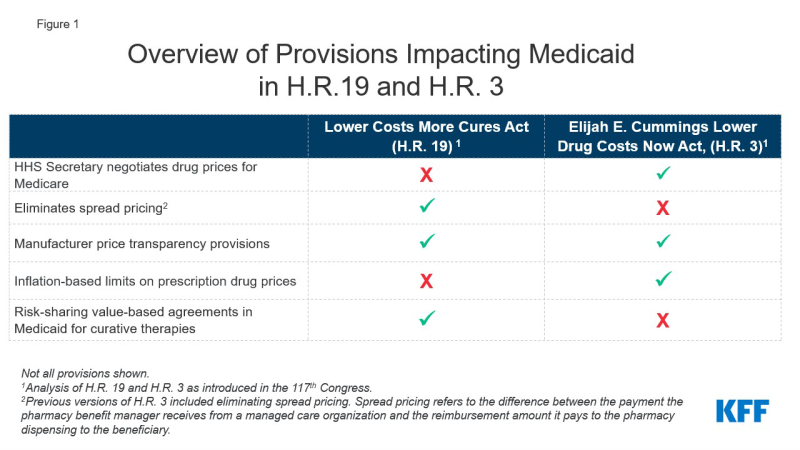

Prescription drug spending has again returned to the policy agenda, with Congress and the Administration developing proposals to target drug prices. Though attention in current federal actions is largely focused on Medicare and private insurance drug prices, federal legislation also has been recently introduced or enacted that would affect Medicaid prescription drug policy. In 2019, Medicaid gross drug spending was $66 billion and $37 billion was offset by rebates, resulting in $29 billion of net spending that is shared by states and the federal government. A separate analysis examines an array of leading federal and state policy drug pricing proposals and implications for Medicaid. A number of these proposals are included in two key bills that have been reintroduced in the 117th Congress: H.R. 3, The Elijah E. Cummings Lower Drug Costs Now Act, passed the house in 2019, it did not become law and has since been reintroduced in the 117th Congress. H.R. 19, The Lower Costs More Cures Act has also been reintroduced (Figure 1).

Among the most notable provisions of H.R. 3 are allowing the government to negotiate drug prices for Medicare, which is not allowed under current law, and levying a penalty on drug prices that rise faster than inflation, both of which will likely affect Medicaid drug rebates. H.R. 3 would grant the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) authority to negotiate prices for between 50 and 250 drugs without market competition, with an upper limit based on prices in a set of foreign countries. The negotiated price would apply to both Medicare and could also be used by commercial payers. There is also an additional penalty on Medicare drugs with prices rising faster than inflation. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that Medicaid direct spending would likely increase by about $2.5 billion due to lower rebate payments and higher launch prices due to the Medicare price negotiation and expanded inflation rebates, but federal spending overall would decrease significantly due to the large amount saved on Medicare drugs. Because Medicaid already receives inflationary rebates on drugs that have had large price increases over time, decreasing those prices may lead to lower rebates for the program. For brand drugs, inflation rebates account for about half of the total rebate Medicaid receives.

H.R. 19 includes provisions that would limit spread pricing by pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) in Medicaid. Spread pricing refers to the difference between the payment the PBM receives from the state or MCO and the reimbursement amount it pays to the pharmacy. H.R. 19 would eliminate spread pricing in Medicaid by requiring pass-through pricing and only allow PBMs to collect an administrative fee. The version of H.R. 3 that passed the house in 2019 included a ban on spread pricing in Medicaid but the version reintroduced in 2021 does not. Eliminating spread pricing would generate savings for states and the federal government, through lower payments to MCOs or PBMs, approximately $929 million over ten years.

Both H.R. 3 and H.R. 19 would make information about list prices more accessible in an effort to curb drug costs. H.R. 19 includes a number of transparency provisions targeted both at Medicaid and at drug prices overall, including making National Average Drug Acquisition Cost (NADAC, a federal survey of pharmacies that helps states to determine pharmacy acquisition cost) mandatory, increasing oversight of manufacturer reporting for the MDRP, requiring manufacturers to provide notification and justification for certain price increases and for that information to be made available to the public. H.R. 3 would require the HHS Secretary to make the negotiated prices for drugs available to the public and would also require manufacturers to report to the Secretary of HHS to justify certain price increases. The impact of transparency on actual prices is uncertain, and may not produce savings for the Medicaid program unless transparency results in more accurate reimbursement to pharmacies or more accurate price reporting that increases rebates paid to states and the federal government.

H.R. 19 includes other provisions that have implications for Medicaid. H.R. 19 also includes other Medicaid-specific provisions, including collecting data on prescribing patterns and increased oversight of Medicaid pharmacy and therapeutic (P&T) committees. The bill would also create a state option for risk-sharing value-based agreements for curative drugs that would allow states to pay in installments over time.

Both H.R. 3 and H.R. 19 would make significant changes to the Medicare drug benefit and lower out of pocket costs for beneficiaries and people with private insurance, too. The proposals are expected to yield significant federal savings related to Medicare and private insurance, but there are implications for Medicaid as well. H.R. 3 and H.R. 19 have been introduced in the House and referred to committees, but a relatively narrow Democratic majority in the House and even narrower majority in the Senate could make legislative action difficult. However, if drug pricing proposals that offer significant savings, such as H.R. 3, do gain traction, the federal savings could be used as offsets for policies to advance other health care initiatives, such as lowering the age of Medicare eligibility and improving Medicare benefits or covering people in the Medicaid coverage gap.