8 Questions & Answers about Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico’s debt crisis has been the subject of national media and legislative action over the last several months. Additionally, a number of major news outlets have reported on an impending Puerto Rico health care crisis related to demographic and health care financing issues, and exacerbated by the current economic situation and the growing number of Zika virus transmissions. The following slides provide a quick snapshot of Puerto Rico’s population, as well as current and upcoming issues that are impacting the island’s health care system.

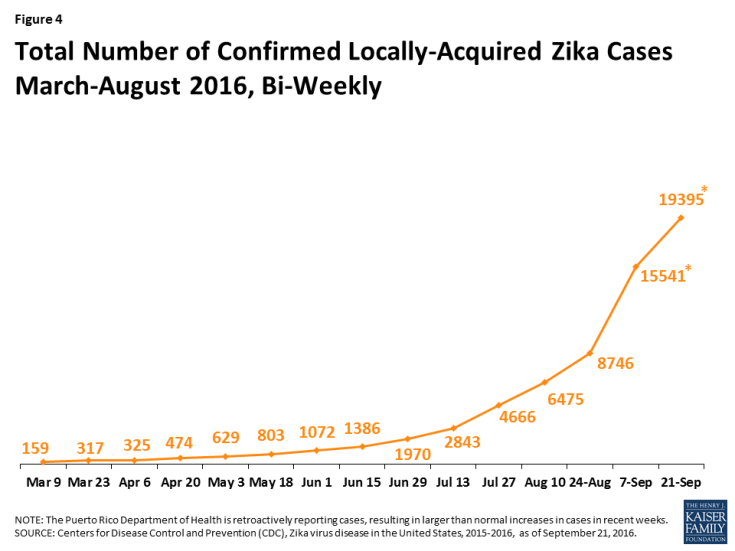

1. How does Puerto Rico compare to the 50 States and DC on Key Demographic and Economic Indicators?

Figure 1: Selected Demographic and Economic Indicators on Puerto Rico, Compared to the 50 States and DC

The Commonwealth of Puerto Rico is a U.S. territory located in the Caribbean, with a population of roughly 3.5 million people. Puerto Ricans are U.S. citizens by birth but they differ from the 50 states and DC on a variety of demographic and economic indicators:

- Puerto Rico is much less racially/ethnically diverse than the 50 states and DC, with nearly its entire population identifying as Hispanic.

- The island fares worse economically, with a poverty rate three times higher than that of the states, and an unemployment rate that is more than twice as high. Additionally, a substantial share of the labor force works in the services industry.1

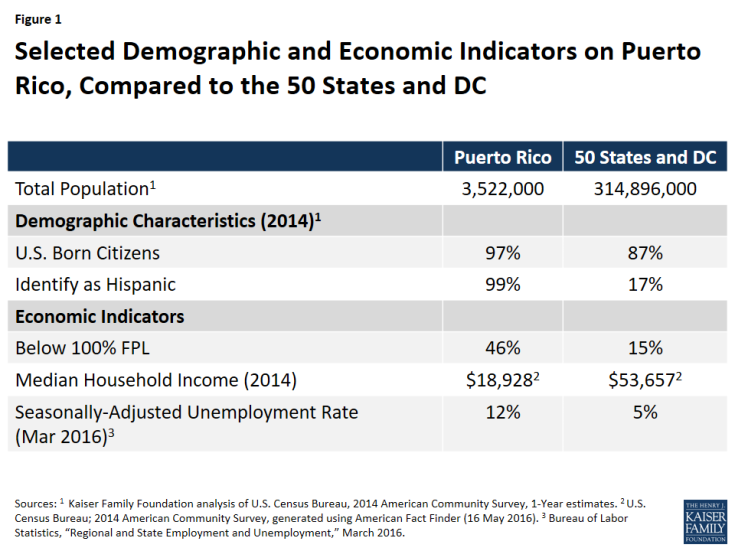

2. How is Puerto Rico’s Population Changing?

Figure 2: Percent Change in Population by Age Group Between 2006 and 2014

Puerto Rico’s economic recession began in 2006.2, 3 Between 2006 and 2014, its population had declined by ten percent, primarily due to the largest outmigration of Puerto Ricans to the U.S. mainland since the 1950s.4,5,6 Young people represent a disproportionate share of those who have migrated, with a 25% drop in the number of people between the ages of 0-14 and a 15% drop in those aged 15-44. The number of seniors on the island has increased by 22% since 2006.

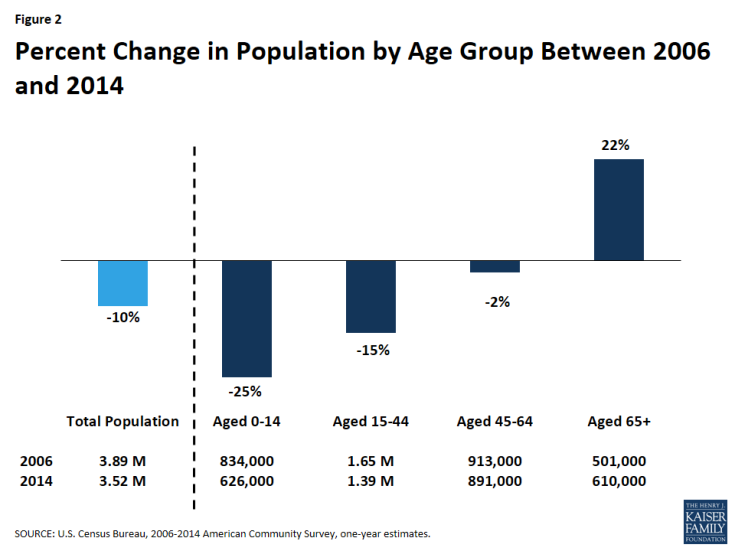

3. How does Puerto Rico compare to the 50 States and DC on Key Health Indicators?

Figure 3: Selected Health Indicators on Puerto Rico, Compared to the 50 States and DC

As with Puerto Rico’s demographic and economic indicators, the island differs from the 50 states and DC on several key health indicators:

- The share of adults reporting fair/poor general health is twice as high in Puerto Rico compared to the rest of the United States.

- HIV and infant mortality rates are also higher in Puerto Rico compared to the rest of the U.S.

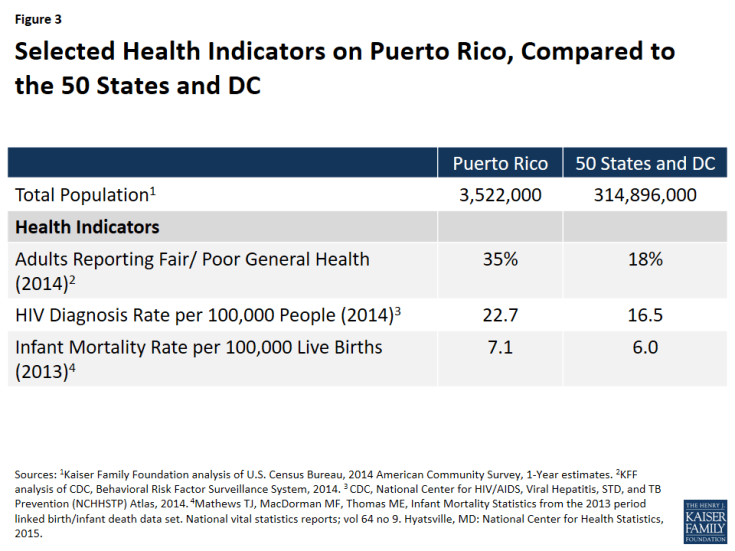

4. How is Zika affecting Puerto Rico?

The first case of locally-acquired Zika virus in the United States was reported in Puerto Rico in December 2015,7 and the number of cases on the island have risen dramatically to 19,395 as of September 21, 2016,8and are expected to continue to grow.9 Locally-acquired Zika is transmitted through the bite of infected mosquitos and the virus can cause microcephaly and other severe fetal brain defects among infected pregnant women. In addition, CDC is investigating the link between Zika and Guillain-Barré Syndrome, a rare disease that causes muscle weakness, and sometimes, paralysis. On August 12, 2016, the US Department of Health and Human Services declared the Zika outbreak in Puerto Rico to be a public health emergency. The declaration allows Puerto Rico to 1) apply for funds to hire and train individuals to assist in controlling the spread of Zika, including outreach and education programs through the U.S. Department of Labor’s National Dislocated Worker Grant, and 2) temporarily reassign staff of local public health department to help combat the spread of Zika.10 The virus poses a public health and financial challenge to the island—according to the CDC, the dollar amount of caring for a single child with birth defects is estimated to be in the millions.11

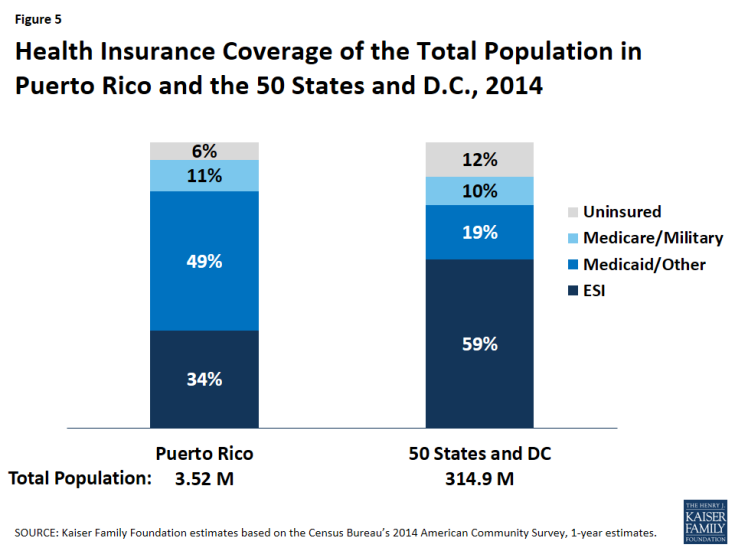

5. What is the Health Coverage of the Population?

Figure 5: Health Insurance Coverage of the Total Population in Puerto Rico and the 50 States and D.C., 2014

Owing in part to high unemployment and poverty rates, almost half of Puerto Ricans are covered by Medicaid, while about one-third are covered by Employer Sponsored Insurance (ESI). An additional 11% of the population is covered by Medicare. Puerto Rico’s Medicaid and Medicare programs are delivered predominantly through managed care.12,13

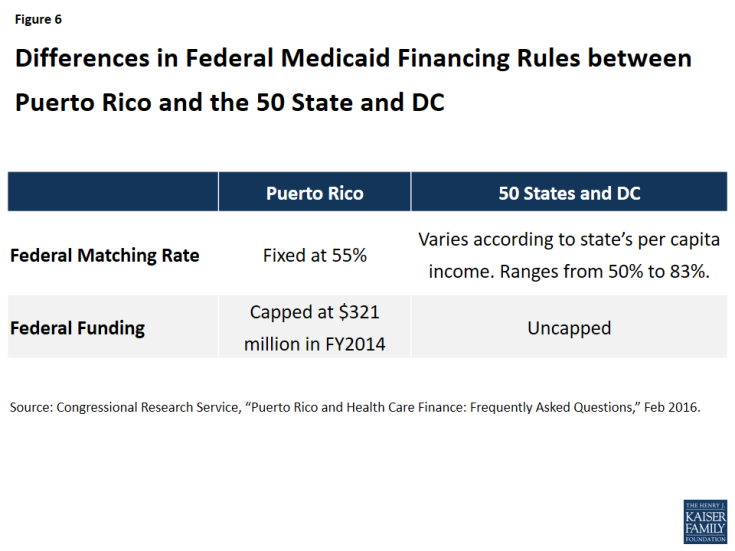

6. How Does Medicaid Funding in Puerto Rico Compare to the States?

Figure 6: Differences in Federal Medicaid Financing Rules between Puerto Rico and the 50 State and DC

While Medicaid covers a large part of the Puerto Rican population, federal Medicaid funding to the island differs from that of the 50 states and DC in two important ways. While the latter receive a federal matching rate that ranges from 50%-83%, depending on the per capita income of the state in a given year, Puerto Rico’s federal matching rate is fixed at 55%. Moreover, unlike the 50 states and DC, Puerto Rico’s annual federal Medicaid allotment is capped, and the island generally exhausts its federal Medicaid allotment prior to the end of the fiscal year.14,15

Additionally, Medicare Advantage (MA) payment rates in Puerto Rico are substantially lower than that of the states,16 leading to lower reimbursement rates to providers and plans. CMS has issued a final rate notice for Medicare Advantage Payment Policies for CY 2017 that are expected to increase revenue for MA plans in Puerto Rico.17

7. What is the Breakdown of Puerto Rico’s Federal Medicaid Funding?

The ACA made two temporary sources of Medicaid funding available to Puerto Rico in addition to its annual Medicaid cap. The first funding source is a $5.5 billion allotment available between July 2011 and September 2019. Puerto Rico has relied heavily on this allotment and in FY 2014, it made up 68% of total federal Medicaid funding to the territory. In that same fiscal year, Puerto Rico had used 42% of the $5.5 billion. The second source of funding was a $925 million allotment the island received in lieu of funds it would have received for creating its own Marketplace. These funds are also available through FY 2019 and can only be accessed after the first source of ACA funding has been depleted.18 Both sources of funding are estimated to be exhausted by the end of FY 2017.19 Absent reauthorization of ACA funds, Puerto Rico will face additional challenges financing its Medicaid program.

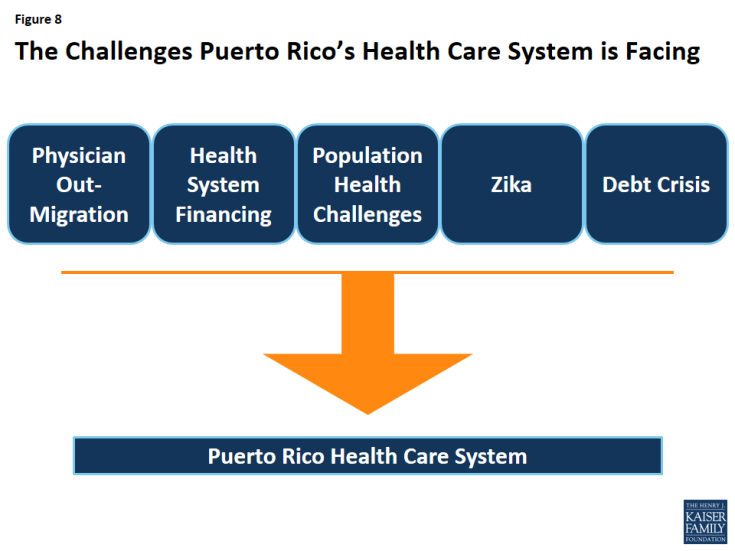

8. What Challenges is Puerto Rico’s Health Care System Facing?

Figure 8: The Challenges Puerto Rico’s Health Care System is Facing

Puerto Rico’s health care system faces a number of challenges—as young people migrate to the U.S. mainland, seniors now make up a larger share of the population than they did a decade ago; health indicators are worse than that of the rest of the United States; the island’s public insurance system covers over half the population and faces financing challenges; and the number of Zika virus transmissions have increased substantially over the last few months, and are expected to continue. In addition, the island has experienced a substantial outmigration of physicians to the U.S. mainland, particularly among specialists and sub-specialists.20,21,22

The debt crisis is making it more difficult for the island to respond to these issues. Delayed payments by the government to Medicare and Medicaid managed care plans have caused a cascade of payment delays to medical providers and suppliers, and there have been reports of power and water shortages in hospitals, delays in the arrival of medical supplies, the laying off of hospital workers, and the closure of hospital floors and service areas. As the number of Zika cases mount, Puerto Rico’s health care system and economy is likely to face even greater challenges.23,24 ,25

After several months of congressional debate, the Puerto Rico rescue bill known as PROMESA was signed into law on June 30, 2016. The law places Puerto Rico’s fiscal affairs under a federal oversight board, allows for the restructuring of some of Puerto Rico’s debts, and includes a temporary stay on bondholder lawsuits.26 While the law represents a first step toward economic recovery, it does not address the critical issues facing Puerto Rico’s health care system, including the impending expiration of ACA funding, the limits imposed by the capped Medicaid financing structure, or the mounting cases and future consequences of Zika on the island.

Endnotes

Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, Government Development Bank for Puerto Rico, Economic Fact Sheet, March 2016, http://www.gdb-pur.com/economy/fact-sheet.html.

The White House, Puerto Rico’s Economic and Fiscal Crisis, https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/factsheet-puertoricoseconomicandfiscalcrisis.pdf.

The National Puerto Rican Chamber of Commerce. Puerto Rico’s Economy: A brief history of reforms from the 1980s to today and policy recommendations for the future, March 19, 2015, http://nprchamber.org/files/3-19-15-Puerto-Rico-Economic-Report.pdf.

United States Census Bureau, Population, International Data, http://www.census.gov/population/international/data/idb/region.php?N=%20Results%20&T=13&A=separate&RT=0&Y=2026,2027,2028,2029,2030,2031,2032,2033,2034,2035,2036,2037,2038,203

Jens Manuel Krogstad, Mark Hugo Lopez, and Drew Desilver, “Puerto Rico’s Losses are not just economic, but in people, too” (Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center, July 2015) http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/07/01/puerto-ricos-losses-are-not-just-economic-but-in-people-too/.

Annie Mach, Puerto Rico and Health Care Finance: FAQ (Washington: D.C.: Congressional Research Service, February 2016), https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R44275.pdf.

Dirlikov E, Ryff KR, Torres-Aponte J, et al. Update: Ongoing Zika Virus Transmission — Puerto Rico, November 1, 2015–April 14, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:451–455. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6517e.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Zika virus disease in the United States, 2015-2016, as of May 18, 2016.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Zika and Guillain-Barre Syndrome, April 14, 2016, http://www.cdc.gov/zika/about/gbs-qa.html.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), HHS declares a public health emergency in Puerto Rico in response to Zika outbreak, August 12, 2016, https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2016/08/12/hhs-declares-public-health-emergency-in-puerto-rico-in-response-to-zika-outbreak.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Transcript for CDC Telebriefing: Zika Summit Press Conference, April 1, 2016, http://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2016/t0404-zika-summit.html.

Annie Mach, Puerto Rico and Health Care Finance: FAQ (Washington: D.C.: Congressional Research Service, February 2016), https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R44275.pdf.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), Managed Care in Puerto Rico, August 2014, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid-chip-program-information/by-topics/delivery-systems/managed-care/downloads/puerto-rico-mcp.pdf.

Annie Mach, Puerto Rico and Health Care Finance: FAQ (Washington: D.C.: Congressional Research Service, February 2016), https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R44275.pdf.

David Orenstein, Stark Medicare Advantage Disparities Present in Puerto Rico, (Providence, Rhode Island: Brown University, April 25, 2016), https://news.brown.edu/articles/2016/04/puertorico.

Puerto Rico Medicare Coalition for Fairness, “Action Needed For Healthcare in PR,” February 13, 2015, http://nebula.wsimg.com/1bd5367a289dc65699c178818d0739a7?AccessKeyId=C2485EFE08948AE5AAE0&disposition=0&alloworigin=1.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), Supporting Medicare in Puerto Rico, April 4, 2016, https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2016-Fact-sheets-items/2016-04-04-2.html.

Annie Mach, Puerto Rico and Health Care Finance: FAQ (Washington: D.C.: Congressional Research Service, February 2016), https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R44275.pdf.

“HHS FY 2017 Budget in Brief-CMS-Medicaid,” CMS, accessed May 25, 2016.

Pedro R. Pierluisi, Re: Formal Comment Letter on Proposed Rule (CMS-1590-P), (September 4, 2012), http://www.colegiomedicopr.org/docs/9.4.12%20Rep%20Pierluisi%20(PR)%20Comment%20Letter

Gretchen Sierra-Zorita, “Puerto Rico’s Unseen Crisis,” CNN (May 10, 2016), http://www.cnn.com/2016/05/10/opinions/puerto-rico-health-crisis-gretchen-sierra-zorita/.

Greg Allen, “SOS: Puerto Rico Is Losing Doctors, Leaving Patients Stranded,” (March 12, 2016), http://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2016/03/12/469974138/sos-puerto-rico-is-losing-doctors-leaving-patients-stranded.

Nick Timiraos, “Treasury Secretary Jacob Lew Tours Puerto Rico to Urge Action in Congress,” Wall Street Journal (May 9, 2016), http://www.wsj.com/articles/treasury-secretary-jacob-lew-tours-puerto-rico-to-urge-action-in-congress-1462814534

Vann R. Newkirk II, “Will Puerto Rico’s Debt Crisis Spark a Humanitarian Disaster?” The Atlantic, (May 9, 2016), http://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2016/05/puerto-rico-treasury-visit/482562/.

Lizette Alvarez and Abby Goodnough, “Puerto Ricans Brace for Crisis in Health Care,” New York Times (August 2, 2015), http://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/03/us/health-providers-brace-for-more-cuts-to-medicare-in-puerto-rico.html.

- S. 2328-PROMESA, 114th Congress (2015-2016), Public Law No: 114-187 (June 30, 2016), https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/4900.