An Overview of Actions Taken by State Lawmakers Regarding the Medicaid Expansion

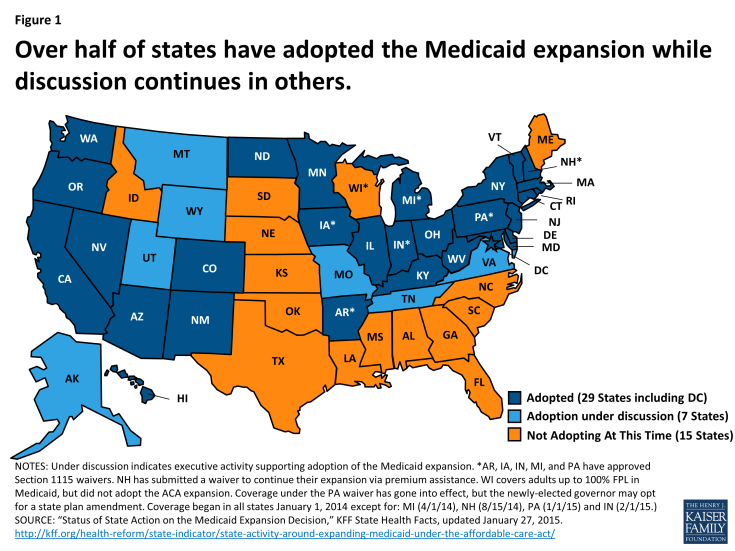

As enacted, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) broadened Medicaid’s role, making it the foundation of coverage for nearly all low-income Americans with incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) ($16,242 per year for an individual in 2015). However, the Supreme Court ruling on the ACA effectively made the decision to implement the Medicaid expansion an option for states. For those that expand, the federal government will pay 100 percent of Medicaid costs of those newly eligible for Medicaid from 2014 to 2016. The federal share gradually phases down to 90 percent in 2020, where it remains well above traditional federal medical assistance percentage (FMAP) rates. As of January 2015, 29 states (including the District of Columbia) adopted the Medicaid expansion, though debate continues in other states.1 (Figure 1) State lawmakers have had different responses to the Medicaid expansion. While it does not cover how every state has enacted the Medicaid expansion, this fact sheet highlights some of the different actions state lawmakers have taken in response to the Medicaid expansion. Each state’s circumstances are unique; the actions taken by one state may not apply to another state’s circumstances.

Figure 1: Over half of states have adopted the Medicaid expansion while discussion continues in others.

Overview of the Processes Required to Adopt the Medicaid Expansion

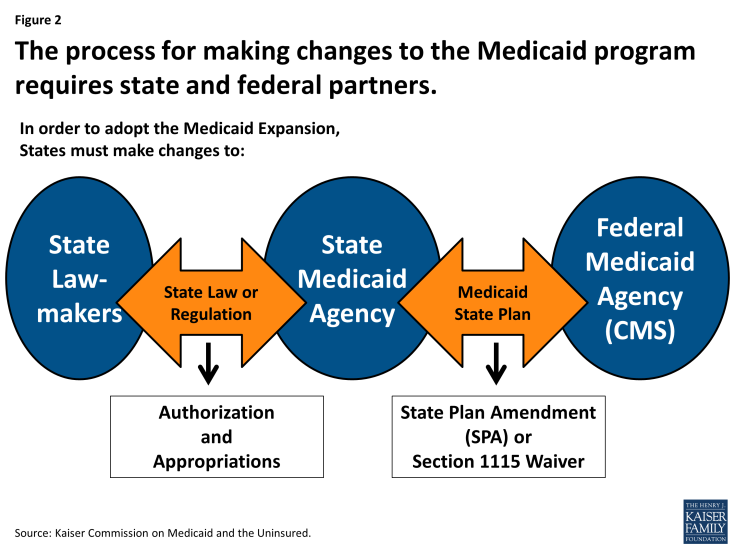

Medicaid is a jointly-operated program; state Medicaid agencies must work with Federal partners to adopt the Medicaid expansion. The relationship between the state Medicaid agencies and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the federal agency administering the Medicaid program, is governed by a document called a Medicaid state plan. A Medicaid state plan describes how each state will operate its program, which is submitted to and approved by CMS. To make a change in its Medicaid program, such as adopting the Medicaid expansion, the state Medicaid agency must submit and receive CMS approval of either a state plan amendment (SPA), which is used to make program changes that are allowed under current law, or less commonly a waiver request, which is negotiated agreement involving changes to the operation of the state’s program that are not allowed under federal Medicaid law.2 (Figure 2) To date, 24 of the 29 states that have adopted the Medicaid expansion have done so through filing a SPA; only five states have received Section 1115 waiver approval to implement the ACA Medicaid expansion.3

Figure 2: The process for making changes to the Medicaid program requires state and federal partners.

However, before working with federal partners, state Medicaid agencies often must work with state lawmakers to obtain authorization and appropriations before implementing the Medicaid expansion. (Figure 2) In order to make changes to Medicaid policy, such as expanding eligibility under the Medicaid expansion, states must work with lawmakers (governors and/or legislatures) to make changes to either state laws and/or state regulations. Each state has different rules about which kinds of Medicaid policy changes, if any, can be authorized through changes in regulation (and therefore by agencies at the direction of the governor) or must be made through changes to state law or statute (and therefore require legislative approval.) For example, some states require state legislative action before state plan amendments or Section 1115 waiver requests can be submitted by the state Medicaid agency to CMS for federal approval and others do not. States also vary on whether legislative action is required to authorize changes to Medicaid benefits, cost-sharing and other types of Medicaid policy changes.4 This varies, at least in part, on how the Medicaid program was incorporated into state statute when the state originally enacted the program decades ago and the changes to rules and regulations enacted in the years since. In addition to authorization, state Medicaid agencies must also work with state lawmakers to obtain appropriations to fund the Medicaid policy change(s). Some states require legislative action to appropriate federal dollars as well as state dollars; others do not.

Examples of State Lawmaker Responses to Medicaid Expansion

State lawmakers play a key role in determining if and how their state may adopt the Medicaid expansion. Both Republican and Democratic state lawmakers have responded in differing ways to the Medicaid expansion; responses have also changed over time. The following sections walk through some of the different ways state lawmakers have responded to the Medicaid expansion.

Standard Legislative Process

Many of the states that have adopted the Medicaid expansion have done so through the standard legislative process – legislation was passed authorizing the Medicaid expansion (either through a stand-alone bill or as part of budget legislation.) For example, Minnesota5 and Maryland6 passed legislation during their 2013 regular legislative sessions to enact the Medicaid expansion. Other states, such as New York7 and New Mexico8, included the Medicaid expansion as part of budget bills passed in 2013. In each of these states, the Governor and legislature supported the Medicaid expansion. The standard legislative process has also worked in some states where adopting the Medicaid expansion was initially supported by one branch but not the other. For example, in Arizona, Governor Brewer strongly supported adopting the Medicaid expansion; after lobbying legislators and building public support, legislators passed the state’s budget with the Medicaid expansion.9

While Section 1115 waivers require additional steps to obtain federal approval, the legislative process remains largely the same at the state level. The majority of states that have adopted the Medicaid expansion to date have done so within federal rules and options to receive the associated enhanced federal matching funds for newly eligible, in other words, through SPAs. However, a limited number of states have obtained or are seeking approval through Section 1115 waivers to implement the expansion in ways that extend beyond the flexibility provided by the law.10 While Section 1115 waivers require additional steps to obtain federal approval, the process at the state level may be largely the same at the state level as if the state were adopting the expansion through a SPA. For example, lawmakers in Iowa, New Hampshire and Michigan approved legislation adopting the Medicaid expansion through their standard legislative process. While the legislation outlined their alternative Medicaid expansion requests and conditioned approval on federal waiver approval within a set timeframe, the legislatures delegated development and submission of the final waiver proposal to the state Medicaid agencies. More recently, governors in some states, such as Utah and Tennessee, have instead started negotiations with CMS officials to develop a waiver proposal that is likely to be approved at the federal level. Once a preliminary agreement in principle has been reached, these governors have now started working with their legislatures to obtain their approval before formally submitting the request to CMS.

One branch of government can stop adoption of the Medicaid expansion. State Lawmakers have differed on their support or opposition to the Medicaid expansion. In states such as Missouri and Virginia, Governors Nixon and McAuliffe have also both expressed strong support for the Medicaid expansion, initiating statewide campaigns for adoption of the expansion in their respective states. However, each of these Governors has faced strong opposition from their respective state legislatures; Medicaid expansion has not been adopted in either state at this time. Sometimes, even one body of the state legislature has stopped passage of state legislation adopting the Medicaid expansion. For example, in Florida, Governor Rick Scott announced his support of adopting the Medicaid expansion in February 2013.11 The Senate passed legislation that adopted an alternative Medicaid expansion proposal; however, strong opposition in the House of Representatives prevented final passage of the legislation. 12 In other cases, governor opposition to adoption of the expansion has prevented action. For example, in Maine, the legislature has passed multiple bills authorizing the Medicaid expansion, but each has been vetoed by Governor LePage; override votes have fallen short of the two-thirds majority vote needed each time.13

Some states have enacted laws prohibiting Medicaid expansion without legislative approval. While most states have adopted the Medicaid expansion after agreement has been reached by both governors and state legislatures, some legislatures have sought to ensure that legislative approval is required before adoption of the Medicaid expansion can take effect. In March 2013, Governor McCrory of North Carolina signed legislation that prevented any department, agency or institution of the state from expanding eligibility under the ACA Medicaid expansion in North Carolina unless directed to do so by the General Assembly.14 Similar stand-alone legislation was also passed in other states such as Georgia15 and Tennessee.16 Legislatures in other states, such as Virginia, have included language requiring legislative approval before implementing the Medicaid expansion in state budgets.17 Similar legislation that would prohibit the Governor or executive agencies from implementing the Medicaid expansion without legislative approval is under consideration in Montana.18

Alternative Processes

In a few select cases, the Medicaid expansion has been adopted through executive action. While enactment of the Medicaid expansion involved the legislature in most states, at least two states enacted the Medicaid expansion through executive order – Kentucky and West Virginia. In May 2013, Governor Beshear of Kentucky and Governor Tomblin of West Virginia issued executive orders enacting the Medicaid expansion in their states.

The need to appropriate federal funds has also raised some challenges in states seeking adoption of the Medicaid expansion. As part of state budget processes, some states require that all funding be appropriated, including that from federal funds. For example, after the Arkansas legislature approved authorizing language for the Medicaid expansion (the Private Option)19, the state legislature also had to pass legislation to appropriate the federal dollars that fund the Private Option; all appropriations in Arkansas require a three-fourths majority vote in each chamber, a higher threshold than in most states. 20 Other states delegate appropriation authority in select cases to other government bodies. For example, in Ohio, some spending decisions are delegated to the state’s Controlling Board. The role of the board is to “provide a mechanism for handling limited day-to-day adjustments needed in the state budget,” without requiring the full legislature to meet; over time its role has been also to provide greater legislative oversight of executive action.21 After Ohio’s budget for SFYs 2014-2016 passed in June 2013 without appropriations for the Medicaid expansion, the Ohio Medicaid Director submitted a request that the Controlling Board approve the appropriation of federal funds for the Medicaid expansion. The Controlling Board approved the appropriation in October 2013.22

Some states have passed legislation that created taskforces or study groups to further examine the issue of Medicaid expansion and make a recommendation to the legislature. For example, as part of a compromise deal reached by the Governor and the legislature in 2013, Virginia established the Medicaid Innovation and Reform Commission (MIRC); this committee was charged with monitoring the development of Medicaid reform proposals, such as the expansion of managed care among others. If the MIRC determined that specific Medicaid cost-reduction and efficiency benchmarks had been met, it could then vote to implement the Medicaid expansion.23 However, the committee was later eliminated as part of the FY 2015-2016 budget passed the following year. Additional legislation establishing study groups or taskforces to examine the Medicaid expansion and broader Medicaid reforms has previously been enacted in a number of states, such as Wyoming; this taskforce recently recommended the SHARE plan, an alternative Medicaid expansion proposal. As in other states, the recommendation of the taskforce is not binding and still requires legislative approval in addition to Governor support before being adopted.

In a few instances, state lawmaker actions adopting the Medicaid expansion have been challenged in court. For example, the executive orders adopting the Medicaid expansion and enacting the state’s Marketplace – kynect – in Kentucky were challenged in court. Eventually the judge upheld the executive order based on existing state law that gave the Secretary of Health and Family Services authority “to take advantage of all federal funds that may be available for medical assistance…the secretary…may by regulation comply with any requirement that maybe imposed or opportunity that may be presented by federal law.”24 A court case has also been brought in Arizona, where state legislators are challenging the budget legislation that enacted the Medicaid expansion. Part of this legislation called for the implementation of a new hospital provider fee to fund state costs of the Medicaid expansion. According to the plaintiffs, which include the State Senate President, Senator Biggs, the fee is a tax, which under Arizona’s constitution, requires two-thirds majority to approve as opposed to the simple majority that approved the legislation. After the State Supreme Court ruled that the plaintiffs had standing to bring the lawsuit, the case has been referred back to Maricopa County Superior Court.25

While discussed in some states, no state has included a ballot initiative on the adoption of the Medicaid expansion. For example, in Montana, supporters of the Medicaid expansion sought to include a ballot initiative on the state’s 2014 ballot. If approved by voters in the state, it would have expanded eligibility under the Medicaid expansion; additional legislative action would have been needed to appropriate the funding. However, the initiative failed to collect enough signatures and was not included on the ballot.26

Conclusion

State lawmaker responses to the Medicaid expansion have differed across states. Most states adopted the Medicaid expansion through the standard legislative process after gaining the support of both branches of state government; however a few states have adopted the Medicaid expansion through alternative processes. Each state’s circumstances are unique; the actions taken by one state may not apply to another state’s circumstances.

Endnotes

See Current Status of State Medicaid Decisions, as of January 27, 2015, available at: https://www.kff.org/health-reform/slide/current-status-of-the-medicaid-expansion-decision/.

Robin Rudowitz and Andy Schneider, The Nuts and Bolts of Making Medicaid Policy Changes: An Overview and Look at the Deficit Reduction Act. Kaiser Family Foundation, July 2006. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-nuts-and-bolts-of-making-medicaid/.

Robin Rudowitz, Samantha Artiga and MaryBeth Musumeci. The ACA and Medicaid Expansion Waivers. Kaiser Family Foundation, updated February 2015. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-aca-and-recent-section-1115-medicaid-demonstration-waivers/.

National Health Law Center and National Association of Community Health Centers, Role of State Law in Limiting Medicaid Changes. February 2008. http://www.nachc.org/client/NHELP-NACHC-St-by-St-Chart-Final.pdf

H.F. 9, 88th Minnesota Legislature (enacted 2013.) https://www.revisor.mn.gov/bills/bill.php?b=house&f=HF9&ssn=0&y=2013.

Governor Mark Dayton, State expands health coverage for 35,000 Minnesotans. (Press Release, Governor of Minnesota,) February 19, 2013. http://mn.gov/governor/newsroom/pressreleasedetail.jsp?id=102-55000.

H.B. 0228, Maryland General Assembly 2013 Regular Session (enacted 2013.) http://mgaleg.maryland.gov/webmga/frmMain.aspx?pid=billpage&stab=01&id=hb0228&tab=subject3&ys=2013RS.

The House Fiscal and Policy Note for this bill indicates that there is “no legal requirement that Maryland enact legislation to participate in the Medicaid expansion…however, all previous expansions of the Maryland Medicaid program have been done through legislation.”

Department of Legislative Services, Fiscal and Policy Note Revised: Maryland Health Progress Act of 2013 (House Bill 228.) (Maryland General Assembly,) 2013. http://mgaleg.maryland.gov/2013RS/fnotes/bil_0008/hb0228.pdf.

A. 03006, New York State Assembly – 2013 Legislative Session (enacted 2013). http://assembly.state.ny.us/leg/?bn=S02606&term=2013.

H.B. 2, New Mexico Legislature - 2013 Legislative Session (enacted 2013). http://www.nmlegis.gov/lcs/legislation.aspx?chamber=H&legtype=B&legno=%20%20%202&year=13.

H.B. 2010, Fifty-first Legislature – Special Session (enacted 2013.) http://www.azleg.gov/DocumentsForBill.asp?Bill_Number=HB2010&Session_ID=111.

Robin Rudowitz, Samantha Artiga and MaryBeth Musumeci. The ACA and Medicaid Expansion Waivers. Kaiser Family Foundation, updated February 2015. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-aca-and-recent-section-1115-medicaid-demonstration-waivers/.

Governor Rick Scott, We Must Protect the Uninsured and Florida Taxpayers with Limited Medicaid Expansion. (Office of the Governor,) February 20, 2013. http://www.flgov.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/2-20-13-REMARKSFORDELIVERY.pdf.

CS/SB 1816, Florida State Legislature –Regular Session (not enacted, 2013.) http://www.myfloridahouse.gov/Sections/Bills/billsdetail.aspx?BillId=50869.

L.D. 1066 “An Act to Increase Access to Health Coverage and Qualify Maine for Federal Funding,” 126th State of Maine Legislature (not enacted, 2013.) http://legislature.maine.gov/LawMakerWeb/summary.asp?ID=280047868

L.D. 1578 “An Act to Increase Health Security by Expanding Federally Funded Health Care for Maine People,” 126th State of Maine Legislature (not enacted, 2014.) http://legislature.maine.gov/LawMakerWeb/summary.asp?ID=280050715.

S. 4, North Carolina State Legislature – 2013-2014 Session (2013.) http://www.ncleg.net/gascripts/BillLookUp/BillLookUp.pl?Session=2013&BillID=S4.

H. B. 990, Georgia General Assembly 2013-2014 Regular Session, (2014.) http://www.legis.ga.gov/Legislation/en-US/display/20132014/HB/990.

H.B. 0937, 108th Tennessee General Assembly (2014.) http://wapp.capitol.tn.gov/apps/Billinfo/default.aspx?BillNumber=HB0937&ga=108.

After a long protracted debate over the state’s budget bill around the Medicaid expansion, legislators in Virginia passed a budget bill without appropriations for the Medicaid expansion that also included an amendment, proposed by Senator Stanley, to prevent the governor from implementing the expansion on his own authority without legislative approval. Governor McAuliffe signed the budget legislation, but used his line-item veto authority to remove the Stanley amendment along with other items. However, the Speaker of the House later ruled that the line-item veto of the Stanley amendment was outside the Governor’s authority as it did not delete the entire line item but only a portion; the line item in question related to the appropriation for the state’s entire Medicaid program. After the General Assembly voted and approved other line-items vetoes, the budget became law with the Stanley amendment intact.

Laura Snyder, Kathleen Gifford, Eileen Ellis and Jenna Walls, Putting Medicaid in the Larger Budget Context: An In-Depth Look at Four States in FY 2014 and 2015. (Kaiser Family Foundation,) October 2014. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/putting-medicaid-in-the-larger-budget-context-an-in-depth-look-at-four-states-in-fy-2014-and-2015/.

H.B. 256, Montana Legislature 2015 Regular Session (2015.) http://leg.mt.gov/css/default.asp. .

H.B. 1143, 89th General Assembly of Arkansas (2013.) http://www.arkleg.state.ar.us/assembly/2013/2013R/Pages/BillInformation.aspx?measureno=HB1143.

H.B. 1219, 89th General Assembly of Arkansas (2013.) http://www.arkleg.state.ar.us/assembly/2013/2013R/Pages/BillInformation.aspx?measureno=HB1219

“Authority – Actions Related to State Finances & the Budget Arena”. Office of Budget and Management website, Accessed February 10, 2015. http://obm.ohio.gov/ControllingBoard/authority.aspx.

Controlling Board Manual. (Ohio Office of Budget and Management,) revised February 2012. http://obm.ohio.gov/ControllingBoard/doc/manual/CB_Manual_2012.pdf .

“Minutes of the October 21, 2013 Meeting of the Controlling Board.” (Ohio Office of Budget and Management,) Accessed February 2015. http://obm.ohio.gov/ControllingBoard/doc/minutes/CB-minutes_2013-10-21.pdf.

Medicaid Innovation and Reform Commission, “About the Commission”, (Virginia General Assembly.) Accessed August 2014. http://mirc.virginia.gov/about.html.

David Adams, et al v. Commonwealth of Kentucky et al, No. 13-CI-605 (Franklin Circuit Court – Division 1, September 3, 2013.) http://www.adea.org/uploadedFiles/ADEA/Content_Conversion_Final/policy_advocacy/Documents/emailDist/5PAGES.pdf

Kentucky Revised Statutes (KRS) 205.520 http://www.lrc.ky.gov/Statutes/statute.aspx?id=7700.

Andy Biggs, et al v. Governor Janice Brewer et al, No. CV-14-0132-PR (Supreme Court of the State of Arizona, December 31, 2014.) http://www.azcourts.gov/Portals/0/OpinionFiles/Supreme/2014/CV-14-0132-PR.pdf

Ballot Issue #14 I-170. Received by Secretary of State January 22, 2014. Accessed February 12, 2015. http://sos.mt.gov/elections/2014/BallotIssues/index.asp.