Key Questions About Nursing Home Regulation and Oversight in the Wake of COVID-19

| Key Takeaways |

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to renewed interest among policymakers, the media, residents, and their families in nursing home regulation and oversight, as residents and staff are at increased risk of infection due to the highly transmissible nature of the coronavirus, the congregate nature of facility settings, and the close contact that many workers have with patients. Certification of nursing home compliance with federal Medicare and/or Medicaid requirements generally is performed by states through regular inspections known as surveys. Federal regulations issued in 2016 require facilities to have an infection control and prevention program and a written emergency preparedness plan. This issue brief answers key questions about nursing home oversight and explains how federal policy has changed in light of COVID-19. Key findings include:

|

Introduction

There has been sustained attention on nursing homes in the wake of COVID-19, from the initial widespread outbreak at a facility in Washington State to the disproportionate number of cases and deaths among residents and staff nationally throughout the pandemic. Nursing home residents include 1.2 million seniors and nonelderly people with disabilities living in over 15,000 facilities. These residents and the 3 million people who work in skilled nursing or residential care facilities are at increased risk of infection due to the highly transmissible nature of the coronavirus, combined with the congregate nature of facility settings and the close contact that many workers have with patients. If infected, many residents are at increased risk of adverse health outcomes and death from COVID-19, due to old age and/or underlying chronic health conditions. Over 40% of all COVID-19 deaths have been residents or staff of long-term care facilities, with even higher numbers in some states. At the pandemic’s outset, nursing home oversight and response was concentrated at the state level, which led to different protocols across states and facilities, with little federal involvement and substantial shortages of personal protective equipment and coronavirus tests.

As a result of the pandemic’s impact, policymakers, residents, staff, and others have raised questions about whether there has been sufficient federal and state oversight of and guidance for nursing homes, and CMS has released a series of guidance and other policy actions. The Social Security Act authorizes the Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary to establish requirements relating to nursing home residents’ health, safety and well-being as conditions for facilities to receive payment from the Medicare and Medicaid programs. Nursing homes can be certified as Medicare skilled nursing facilities (SNFs)1 and/or Medicaid nursing facilities (NFs).2 Medicare is the primary payer for about 12 percent of nursing home residents, with coverage limited to short-term stays for skilled nursing care or rehabilitation. Medicaid is the primary payer for 62 percent of nursing home residents, covering both short-term skilled nursing care and rehabilitation, as well as long-term care. This brief answers key questions about nursing home oversight and explains how federal policy has changed in light of COVID-19.

1. How are the federal requirements for nursing home oversight enforced?

Certification of nursing home compliance with federal Medicare and/or Medicaid requirements generally is performed by states through regular inspections known as surveys.3 States receive 75% federal matching funds for Medicaid nursing facility survey and certification activities,4 while Medicare SNF survey and certification activities are funded by a discretionary appropriation. Appendix 1 explains the survey process. States also must investigate complaints of facility violations of federal requirements5 and allegations of abuse, neglect, and misappropriation of resident property by nurse aides or other facility service providers6 and conduct periodic educational programs for facility staff and residents about current regulations, policies, and procedures.7

The penalties for facilities found to be out of compliance with federal requirements vary depending on whether the deficiency is determined to immediately jeopardize residents’ health or safety.8 For deficiencies that result in immediate jeopardy, a facility is subject to the appointment of temporary management to oversee operations while deficiencies are corrected or termination from the Medicare and/or Medicaid programs with the safe and orderly transition of residents to another facility or community setting.9 However, a facility may continue to receive Medicare and/or Medicaid payments for up to six months after a deficiency finding, if the state finds that this alternative is more appropriate than program termination. In these instances, the facility must agree to repay Medicare funds, and the state must agree to repay federal Medicaid funds, if corrective action is not taken according to a Secretary-approved plan and timetable. For deficiencies that do not result in immediate jeopardy, a facility may be allowed up to six months to correct deficiencies. A facility that does not come into substantial compliance within three months is subject to denial of Medicare and/or Medicaid payment for all individuals admitted after the deficiency finding date. A facility that is not in substantial compliance within six months is subject to Medicare program termination and discontinuance of Medicaid federal financial participation.

Civil money penalties (CMPs) can be imposed for the number of days a facility is not in substantial compliance or for each instance that a facility is not in substantial compliance.10 CMPs can range from $6,525 to $21,393 for deficiencies constituting immediate jeopardy, and from $107 to $6,417 for deficiencies that do not constitute immediate jeopardy but either caused actual harm or did not cause actual harm but have the potential for more than minimal harm. Per instance CMPs range from $2,140 to $21,393. A portion of CMP funds collected are returned to states and can be used for activities that protect or improve care quality or resident quality of life as approved by CMS, such as supporting and protecting residents during facility closures, relocating residents, supporting resident and family councils and other consumer involvement, facility improvement initiatives such as staff and surveyor training or technical assistance for quality assurance and performance improvement programs, or developing and maintaining temporary manager capability such as recruitment, training, or system infrastructure expenses.

Additional remedies apply to facilities with patterns of deficiencies over time. A facility that is found to provide substandard care quality on three consecutive standard surveys is subject to denial of Medicare and Medicaid payments for all new admissions or entirely and is subject to state monitoring until the facility demonstrates that it has regained and will remain in substantial compliance.11 CMS and/or the state also may direct staff in-service training for facilities with patterns of deficiencies.

2. How have the federal nursing home requirements evolved over time?

Prior to the late 1960s, nursing homes were “essentially unregulated in most states,” and care quality was generally considered to be poor.12 The creation of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965 led to greater federal involvement in nursing home regulation with the establishment of federal criteria to certify facilities. However, concern about care quality and inadequate enforcement continued through the 1970s and 1980s, leading to the appointment of an Institute of Medicine (IOM) committee to recommend changes. The IOM recommendations included incorporating resident assessment, care quality, quality of life, and residents’ rights in federal conditions of participation and making both regulatory requirements and the survey and certification process more “resident-centered and outcome-oriented,” with a shift in emphasis “from facility capability to facility performance.”13 The IOM report also recommended increased federal funding and oversight of state survey agencies and establishing intermediate sanctions short of program termination and facility closure to enforce compliance. Appendix 2 contains additional background about the evolution of federal nursing home oversight.

The IOM recommendations led to changes adopted in the 1987 Nursing Home Reform Act, which established Medicare SNF and Medicaid NF requirements in three main areas: service provision, residents’ rights, and administration and other matters (Appendix Table 1). The Nursing Home Reform Act strengthened federal standards, inspections, and enforcement provisions; merged Medicare and Medicaid standards; required comprehensive resident assessments; set minimal licensed nursing staff requirements; and required inspections to focus on care outcomes.14 Service provision requirements are related to quality of life, care plans, resident assessment, services and activities, nurse aide training, physician supervision and clinical records, social services, and nurse staffing information.15 Facilities must protect and promote specific residents’ rights including free choice, freedom from restraints, privacy, confidentiality, accommodation of needs, grievances, participation in resident and family groups and other activities, examination of survey results, and refusal of certain transfers. Additional requirements govern the use of psychopharmacologic drugs, advance directives, access and visitation, equal access to quality care, admissions, and protection of resident funds. Administration requirements include licensing and life safety code, sanitary and infection control and physical environment standards.

To help address continuing quality concerns, the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA) included some additional reforms. The Nursing Home Transparency and Improvement Act, adopted as part of the ACA, sought to address complex ownership, management, and financing structures that inhibited regulators’ ability to hold providers accountable for compliance with federal requirements. The ACA also incorporated the Elder Justice Act and the Patient Safety and Abuse Prevention Act, which include provisions to protect long-term care recipients from abuse and other crimes.

The 2016 nursing home regulations issued by the Obama Administration were the first comprehensive update in 25 years. The original consolidated Medicare and Medicaid facility participation requirements were issued in 1989, following the Nursing Home Reform Act, and revised in 1991. The 2016 regulations sought to account for ensuing innovations in resident care and quality assessment and an increasingly diverse and clinically complex resident population.16 New requirements added by the 2016 regulations most relevant to issues raised by COVID-19 include those related to infection control, facility assessment, and emergency preparedness (Box 1). The 2016 regulations also revised provisions related to resident rights, adopting a greater emphasis on person-centered care; reporting of abuse and neglect; and transfer and discharge rights. Additionally, the 2016 regulations added a new section on behavioral health services, adopted a competency requirement for determining staffing sufficiency and new staff training program requirements, and implemented ACA requirements for facility quality assurance and performance improvement programs17 and compliance and ethics programs.18 The regulations were implemented in three phases from 2016 through 2019.

| Box 1: 2016 Nursing Facility Regulations Relevant to COVID-19 Pandemic |

| The 2016 regulations require facilities to establish an infection prevention and control program to provide a safe, sanitary, and comfortable environment and help prevent the development and transmission of communicable diseases. The program must include a system for preventing, identifying, reporting, investigating, and controlling infections and communicable diseases for all residents, staff, volunteers, visitors, and other individuals providing services under a facility contract. The program is based on the facility assessment (described below) and must follow “accepted national standards.” The program must include written standards, policies, and procedures for a surveillance system to identify possible communicable diseases before they can spread to others in the facility; when and to whom possible incidents should be reported; standard and transmission-based precautions to prevent infection spread; when and how isolation should be used for a resident; the circumstances under which the facility must prohibit employees with a communicable disease from direct contact with residents or their food; and hand hygiene procedures. The facility also must designate at least one infection preventionist responsible for the program. The program must be reviewed annually, and the facility must provide staff training on the program.

Facilities must conduct an assessment to determine what resources are necessary to care competently for residents during both regular day-to-day operations and emergencies. The facility assessment must consider the resident population; necessary staff competencies; the physical environment, equipment and services necessary to provide care; any ethnic cultural or religious factors that may affect care; facility resources such as buildings and equipment; services such as physical therapy, pharmacy, and specialized rehabilitation; personnel; contracts with third parties; and health information technology. The assessment must be updated as needed and at least annually. Facilities must have a written emergency preparedness plan. This provision was issued in a separate 2016 provider emergency preparedness regulation.19 The plan must be reviewed and updated at least annually. Facilities must train all employees in emergency procedures when they begin to work in facility and periodically review procedures with existing staff. Facilities also must have an emergency preparedness communication plan including a means of providing information about the general condition and location of residents under the facility’s care and a method for sharing appropriate information from the emergency plan with residents and their families. |

In July 2019, the Trump Administration proposed a number of changes to the 2016 regulations, which it said would increase provider flexibility and reduce regulatory burden. The proposed changes, which are still pending, include:

- Removing the existing requirement that the infection preventionist work at the facility at least part-time or have frequent contact with infection prevention and control program staff and instead requiring that the infection preventionist has “sufficient time” at facility to meet program objectives; and

- Modifying current provisions governing the use of psychotropic medications, the grievance process, the timeframe for retaining staffing data, the quality assurance and performance improvement program, and the compliance and ethics program, among other areas.

Also in July 2019, the Trump Administration issued a final regulation that eliminated the existing ban on pre-dispute arbitration agreements.

3. What was the state of nursing home quality before and during COVID-19?

Infection control deficiencies were widespread and persistent in nursing homes prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a May 2020 GAO report.20 The GAO found that “infection prevention and control deficiencies were the most common type of deficiency cited in surveyed nursing homes, with most nursing homes having an infection prevention and control deficiency cited in one or more years from 2013 through 2017 (13,299 nursing homes, or 82 percent of all surveyed homes).” All states had facilities with infection prevention and control deficiencies cited in multiple consecutive years, indicating “persistent problems.” These deficiencies include staff failing to regularly use proper hand hygiene or failing to implement preventive measures to control infection spread during an outbreak, such as isolating sick residents and using masks and other personal protective equipment (PPE). GAO also found that nearly all infection prevention and control deficiencies were classified by surveyors as not severe, meaning the surveyor determined that residents were not harmed, and implemented enforcement actions for these deficiencies were typically rare. GAO plans future reports to examine CMS guidance and oversight of infection control more broadly as well as CMS’s response to COVID-19.

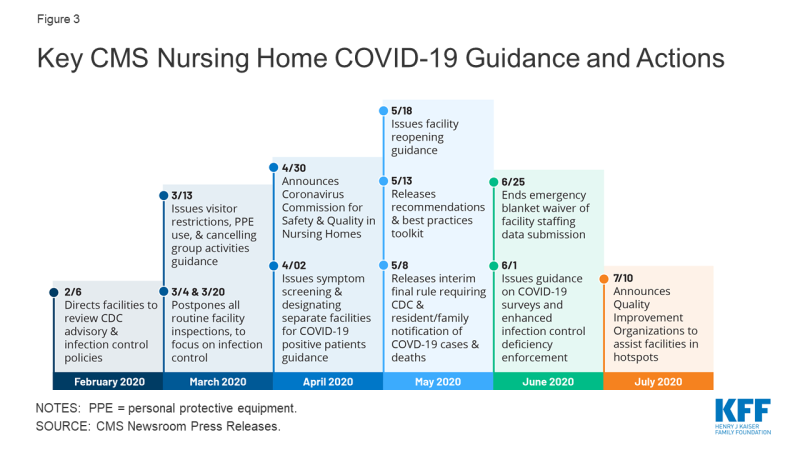

In regular surveys conducted from January 2019 through March 2020, nearly half of facilities received an infection control deficiency (Figure 1). Most facilities (80%) received a deficiency related to resident quality of life or care, and 37% received an abuse/neglect/exploitation deficiency (Figure 1). Just under 20% of facilities received a CMP, with the average amount just over $25,000 (Figure 1). During this same time period, 62% of facilities had substantiated complaints regarding violations of federal requirements, and 39% of facilities had incidents with alleged or suspected resident abuse, neglect, or misappropriation of property (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Share of Nursing Homes with Provider Incidents, Complaints, Civil Monetary Penalties, and Deficiencies, Jan. 2019 – March 2020

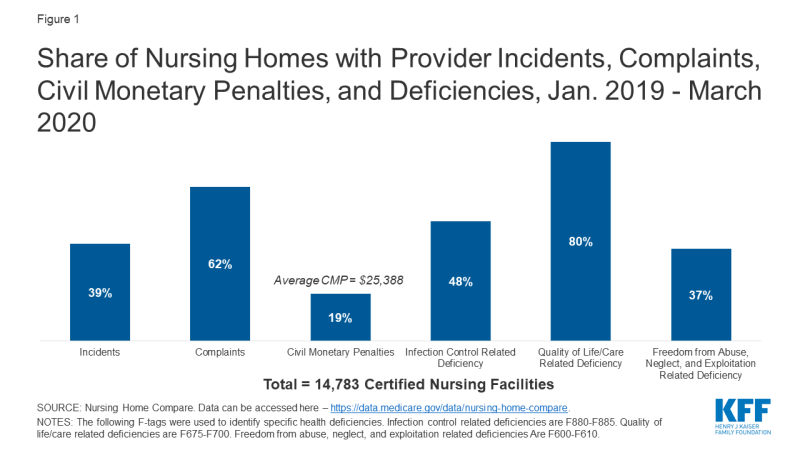

In response to COVID-19, CMS suspended state survey activities in March 2020, except for those related to infection control and immediate jeopardy. Nearly all nursing homes have received these targeted surveys since March 4, 2020, with preliminary inspection reports revealing only a small share with deficiencies (Figure 2). Just 13% of the nearly 6,000 facilities surveyed between March 4 and May 30, 2020 were cited as deficient in meeting any federal requirements. Though nursing homes across the country have experienced high rates of COVID-19 cases and deaths, the data does not point to quality deficiencies as a reason for this occurrence.

Figure 2: Nearly all Nursing Homes Have Received a Targeted Inspection Since March 4, 2020, With Preliminary Inspection Reports Revealing Only A Small Share With Deficiencies

4. How has nursing home oversight changed in light of COVID-19?

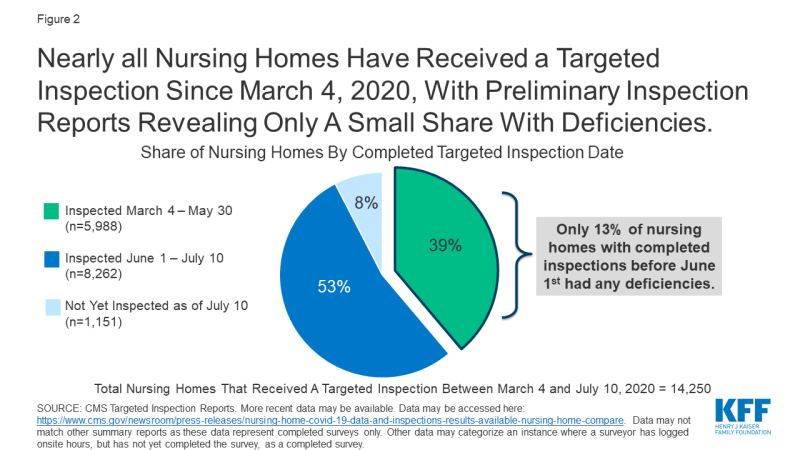

As the number of COVID-19 cases and deaths in nursing homes increased, CMS has issued guidance about how facilities should respond to the pandemic (Figure 3). A February 2020 informational bulletin advised health care facilities to review the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) COVID-19 advisory and recommendations as well as their own infection control policies. As noted above, CMS suspended state survey activities in March 2020, except for those related to infection control and immediate jeopardy. That same month, CMS infection control and prevention guidance advised facilities to screen visitors and staff and about when to transfer residents to and accept those discharged from hospitals. CMS also required facilities to restrict all visitors except for compassionate care circumstances and cancel all communal dining and group activities, released guidance allowing facilities to perform COVID-19 tests, and issued a number of Section 1135 blanket waivers to help facilities’ emergency response. In April 2020, CMS issued guidance directing facilities to screen all staff, residents, and visitors for symptoms, ensure staff use PPE “to the extent available,” and designate separate staff and facilities or units for COVID-19 patients.

In April 2020, CMS announced the formation of an independent commission to conduct a comprehensive assessment of facility response to COVID-19. The commission is expected to make recommendations to protect residents from COVID-19 and improve care delivery responsiveness; strengthen efforts to rapidly identify and mitigate infectious disease transmission in nursing homes; and enhance strategies to improve compliance with infection control policies. The commission also is charged with identifying approaches to better use data to enable federal, state, and local entities to address the current spread of COVID-19 within facilities, analyze the impact of efforts to stop or contain the virus within facilities, and identify best practices to address COVID-19 that CMS or states could adopt. Commission members are to include residents, families, resident/patient advocates, industry experts, clinicians, medical ethicists, administrators, academics, infection control and prevention professionals, state and local authorities, and other experts. Twenty-five Commission members were announced in June 2020, and a final report is expected in fall 2020.

As of May 2020, facilities must report COVID-19 data to the CDC and provide information to residents and their families. Prior to this interim final rule, facilities were not required to report infectious disease information to the CDC, though they typically report to state and/or local health departments. The lack of centralized data contributed to difficulty in tracking disease spread and coordinating dissemination of personal protective equipment and testing supplies. The new rule requires weekly reporting of suspected and confirmed infections among residents and staff including residents previously treated for COVID-19; total deaths and COVID-19 deaths among residents and staff; PPE and hand hygiene supplies in the facility; ventilator capacity and supplies in the facility; resident beds and census; access to COVID-19 testing while a resident is in the facility; staffing shortages; and other information specified by the Secretary.

CMS is publicly reporting the data, and recently announced additional actions based on the data. In July 2020, CMS sent “Task Force Strike Teams” of clinicians and public health officials to 18 nursing homes in six states experiencing an increase in COVID-19 cases. The Teams are focused on determining immediate actions and needed resources to reduce virus spread. In late July 2020, CMS also announced that it would send a weekly list of nursing homes with an increase in cases to states.

The new rule also requires facilities to inform residents, their representatives, and families of confirmed or suspected COVID-19 cases among residents and staff by 5 pm the next calendar day following a single confirmed case or three or more residents or staff with new onset of respiratory symptoms within 72 hours of each other. Facilities also must provide cumulative updates at least weekly by 5 pm the next calendar day following each subsequent occurrence of confirmed infection or whenever three or more residents or staff with new onset of respiratory symptoms occur within 72 hours of each other. Facilities must include information on mitigating actions implemented to prevent or reduce the risk of transmission including whether normal operations will be altered such as restrictions or limitations on visits or group activities. Facilities cannot release personally identifiable information and can communicate through paper notices, a listserv, a website post or recorded phone messages.

In May 2020, CMS issued nursing home reopening recommendations and an informational toolkit with best practices for states to mitigate COVID-19 in nursing homes. The reopening guidance sets out criteria for relaxing restrictions using a phased approach and mitigating the risk of resurgence, including case status in the community, case status in the facility, adequate staffing, access to adequate testing, universal source control (masks, social distancing, and hand washing for visitors), adequate access to PPE for staff, and local hospital capacity. The guidance also includes considerations for allowing visitors and services and for restarting routine state survey activities in each phase. Additionally, quality improvement organizations (QIOs) under contract with CMS are providing technical assistance with a focus on about 3,000 low performing facilities with a history of infection control issues to help identify problems, create and implement an action plan, and monitor compliance. For example, QIOs train staff on proper PPE use, appropriate resident cohorting, and safe resident transfers. States also can request QIO technical assistance targeted to facilities that have experienced an outbreak.

In June 2020, CMS issued additional guidance to states on COVID-19 survey activities and enhanced enforcement for infection control deficiencies. CMS noted that focused infection control surveys pursuant to the March 2020 guidance had been completed in 53 percent of facilities, with wide state variation. As a result, states that have not completed all of these surveys by July 31, 2020 must submit a corrective action plan outlining their strategy to complete these surveys within 30 days. If all surveys still are not complete after the 30-day period, states’ CARES Act FY 2021 allocation may be reduced by up to 10%. Subsequent 30-day extensions could result in additional reductions up to 5%, with funding redistributed to states that have completed their surveys. The CARES Act provided $100 million for nursing home inspections focused on those with COVID-19 community spread from FY 2021 through FY 2023, $81 million of which will be available to state survey agencies. This represents a 6% annual increase in the nursing home survey and certification budget, which had remained at $397 million annually since October 2014. CARES funds may be used for state surveys, strike teams, enhanced surveillance or monitoring of nursing homes, or other state-specific interventions. The June 2020 guidance also establishes enhanced enforcement remedies for infection control deficiencies including directed plans of correction, discretionary denial of payment for new admissions, and CMPs.

The June 2020 guidance also announced three additional survey requirements: (1) states must perform on-site surveys of nursing homes with previous COVID-19 outbreaks by July 1, 2020; (2) states must perform on-site surveys within three to five days of identification of any nursing homes with three or more new suspected or confirmed cases since the last CDC COVID-19 report or one confirmed resident case in a facility that previously was COVID-free; and (3) starting in FY 2021, states must perform annual focused infection control surveys of 20 percent of facilities. States could forfeit 5% of their annual CARES Act allocation for failing to perform these activities.

The June 2020 guidance also authorizes states to expand survey activities to include more routine surveys once a state has entered phase 3 of the nursing home reopening guidance or earlier at state discretion. The expanded activities include complaint investigations that are not immediate jeopardy, revisit surveys to any facility with a removed immediate jeopardy finding but that is still out of compliance, special focus facility and special focus facility candidate recertification surveys, and nursing home and intermediate care facility for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities recertification surveys greater than 15 months. When expanding survey activities, states should prioritize facilities with a history or allegations of noncompliance regarding abuse or neglect, infection control, violations of transfer or discharge requirements, insufficient staffing or competency, or other care quality issues such as falls or pressure ulcers.

In late July 2020, CMS began requiring, rather than recommending, that all staff be tested weekly in nursing homes in states with a 5% or greater positivity rate. HHS also is distributing rapid diagnostic tests to nursing homes in COVID-19 hotspots through a one-time procurement to facilitate on-site testing of residents and staff. CMS and the CDC are offering COVID-19 training to nursing homes, which includes cohorting strategies and using telehealth to mitigate virus spread.

5. What are the key challenges for nursing homes as the pandemic continues?

As the pandemic continues, state survey agencies may face issues related to funding, capacity, and data. CMS will withhold CARES funds from state survey agencies that do not timely complete inspections, but these penalties may be too blunt for agencies whose lack of compliance stems from insufficient funding in the first place. As noted above, prior to the new CARES Act funds, the survey and certification budget had remained flat since 2014. It remains to be seen whether these new funds will be sufficient for state agencies to perform regular surveys as well as increased oversight in the foreseeable future resulting from the pandemic. While facilities are now reporting COVID-19 cases and deaths to CMS, these data are not cumulative prior to May 8, 2020, and it will be important for both state survey agencies and CMS to continue to monitor data and adjust policy guidance and facility oversight as needed.

Nursing facilities also face a number of challenges in their continued pandemic response. Nearly $5 billion in federal provider relief funds has been allocated to nursing facilities to cover health care related expenses or lost revenues attributed to coronavirus. On July 22, 2020, HHS announced that an additional $5 billion from the provider relief fund is being allocated to Medicare-certified long-term care facilities and state veterans homes. These funds may be used to hire additional staff, implement infection control “mentorship” programs with subject matter experts, increase testing, and provide additional services, such as technology so residents can connect with their families if they are not able to visit. As of June 28, 2020, nearly one in three nursing homes nationally report a shortage of staff and/or PPE. Despite federal legislation generally requiring insurers to cover coronavirus testing without cost-sharing, recent federal guidance concludes that insurers do not have to cover coronavirus “testing conducted to screen for general workplace health and safety (such as employee “return to work” programs).” This leaves open the question about who will pay for regular tests needed for facility staff to safely work during the pandemic. It also remains to be seen whether facilities will be able to maintain adequate staffing levels as the pandemic continues. CMS has lifted its emergency waiver of the staffing data submission requirement, and facilities must submit regular staffing data for April through June 2020 by August 14, 2020. Facilities also may be under financial strain due to lower occupancy levels as a result of the pandemic.

Conclusion

While the data and experience to date do not show a direct link between nursing home quality and COVID-19 cases, the pandemic has brought renewed attention to issues of nursing home quality and oversight at the federal and state levels. Nursing home quality concerns have existed for decades. With the current focus on challenges facing nursing homes and state survey agencies as they respond to the pandemic, policymakers may revisit whether federal Medicare and Medicaid requirements should be adjusted to improve oversight and whether additional funding is needed to support providers and agencies to ensure sufficient capacity and resources. These issues are likely to continue to be the subject of policy discussion and debate as long-term care coronavirus cases, particularly in “hotspot states” with wider community transmission continue to rise. While most nursing facilities are Medicare-certified, a small number (315 or 2%) are only Medicaid-certified and therefore appear ineligible for a share of the additional provider relief funds announced on July 22.

More broadly, seniors and people with disabilities who receive long-term services and supports in other settings, such as assisted living facilities, intermediate care facilities for people with intellectual/developmental disabilities, institutions for “mental disease,” and group homes, also are at increased risk of serious illness if infected with coronavirus based on older age and/or chronic health conditions. Unlike nursing homes, other long-term care congregate settings are primarily regulated by states, leading to greater variation in quality protections and lack of standardized reporting about coronavirus cases, deaths, staffing, supplies, and other data necessary to understand and respond to the pandemic and understand its full impact on all people who receive long-term care services and the staff who provide them.