What Worked and What's Next? Strategies in Four States Leading ACA Enrollment Efforts

Lessons Learned

Marketing and Branding

Broad marketing campaigns conducted by the SBMs in all four study states raised public awareness of new coverage options. Stakeholders identified several aspects of the campaigns launched within the study states that contributed to their success, including:

Branding the coverage expansions as state initiatives.Employing lessons learned from the implementation of CHIP, the four study states used state-specific branding for their Marketplaces, which helped detach the coverage expansions from the ACA or “Obamacare” (Figure 1). This state-specific branding proved important, especially in Kentucky and in portions of the other three states, where many residents are distrustful of government programs and not politically supportive of the ACA. Kentucky directed all residents seeking health insurance to “kynect, Kentucky’s Health Care Connection.” It also created animated characters that were representative of different types of Kentuckians who could benefit from the new coverage options, to which stakeholders felt consumers responded well (Figure 2). Stakeholders in Washington indicated that its Marketplace name, “Healthplanfinder,” was intended to sound like a commercial product, which research showed would attract broad interest. Connecticut focused on making its Marketplace, “Access Health CT,” stand out from other entities by choosing orange as a brand color instead of blue, which is used by other entities in the state, including the University of Connecticut and the state seal. Connecticut and Washington also have state-specific names for their Medicaid programs. Connecticut named its Medicaid program for adults Husky D, and Washington changed the name of its Medicaid and CHIP program for children, “Apple Health for Kids,” to “Washington Apple Health” when it expanded to adults.

“I think the approach that the governor took on this whole thing was to not talk about it in terms of Obamacare or the Affordable Care Act. He talked about it in terms of…Kentucky’s health…This is not about President Obama, it’s not about Governor Beshear, it’s not about politics, it’s not about any of these things. It’s about improving the health of our state, so that kind of takes the argument out of it.” –Kentucky Marketplace Official

Conducting statewide marketing across diverse channels. All four states began extensive statewide marketing campaigns for the coverage expansions early and used diverse channels, including television, radio, print, billboards, and social media. Messaging during the early part of open enrollment conveyed a simple, straightforward message about the availability of new coverage options and focused on raising brand awareness of the new Marketplace. Some messaging emphasized the opportunity to improve residents’ health and the availability of financial assistance. Most messaging did not distinguish between Medicaid and Marketplace coverage options.

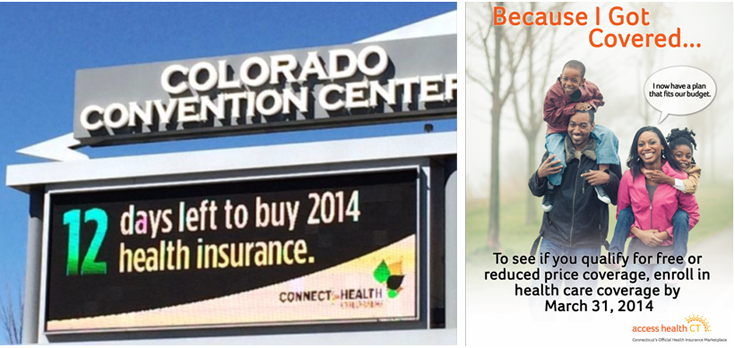

Adapting messaging over time. In all four study states, messaging evolved toward the latter end of open enrollment to focus on the March 31st enrollment deadline and to highlight how consumers have benefited from new coverage options (Figure 3). For example, Connect for Health in Colorado launched a digital billboard that counted down the days until the end of open enrollment. Connecticut created a “Because I Got Covered” print campaign in English and Spanish to disseminate stories about how gaining health insurance helped a variety of different people and to encourage individuals to enroll before the deadline. Stakeholders in Washington also noted that they sought to create a sense of urgency to enroll by running new ads toward the end of open enrollment.

“I think the idea of creating a sense of urgency is always important if you want to get people to take action, especially on something where there’s a deadline…And a lot of our earned media outreach had to do with the deadline and pushing news out there about the deadline and we got our lead organizations out there pushing news on the deadline.” –Washington Marketplace Official

Providing promotional materials for consumers. Stakeholders also noted that promotional materials were helpful tools to garner consumer interest and increase brand awareness for the Marketplaces. For example, Kentucky distributed reusable shopping bags that were extremely popular among consumers. The state gave away over 100,000 bags during open enrollment, including 22,000 bags over the course of 12 days at the state fair. The bags were branded with the kynect logo and caricatures, and had Marketplace contact information, including the website and call center phone number. Kentucky also gave away branded napkins and fans. During the summer before open enrollment, Connecticut Marketplace staff distributed sunscreen on the state’s beaches that had the Access Health CT logo and website address.

Outreach and Enrollment Initiatives

Broad branding and marketing efforts helped raise consumer awareness of new coverage options, and local level outreach and enrollment efforts played a pivotal role in educating consumers and encouraging them to enroll into coverage. Stakeholders highlighted several successful aspects of the study states’ outreach and enrollment efforts, including:

Conducting extensive outreach through numerous local avenues.Stakeholders in the four study states stressed the importance of conducting a broad range of outreach and enrollment initiatives at the local level and identified a variety of avenues where they successfully reached consumers, including churches, college campuses, beauty and barber shops, local grocery or community stores, libraries, extension centers, small businesses, and even people’s homes. They noted the importance of developing trust when reaching consumers through these avenues and of finding a local champion within each community to support outreach efforts. For example, in Connecticut, Navigators worked to engage local small businesses in outreach. To reach consumers in a rural farming community in Kentucky, one assister had a local farmer discuss the importance of insurance. The farmer’s ability to reference specific accidents that might happen on a farm for which it would be important to have health coverage resonated with the community. A number of community-based organizations noted that they promoted health coverage enrollment as part of a broader array of services they offer. In Washington, for example, one organization that provides meals and other services, such as counseling and employment referrals, to homeless and at-risk youth integrated healthcare enrollment into the package of services offered. Because of their existing relationships serving the community, these organizations were often viewed as credible messengers by consumers.

“We built teams of really highly performing assistors that were really good at enrollment and outreach. And we built these teams around our most critical zip codes…These teams would then do zip code specific outreach to small businesses. They hit every barber shop, every nail salon…every PTA meeting. They went to car dealerships and pizza shops and every little mom and pop shop in their zip code.” –Connecticut Marketplace Official

.

“You need to… find that local champion; so, for example, in my community where I grew up, that was my mother …. She set up for me to speak at her church and then stay afterwards and answer anyone’s questions. …Where my grandma lives, we set up an enrollment day at my grandma’s house…”

–Kentucky Assister

Developing customized outreach materials and resources. Assisters indicated that they developed customized outreach materials and resources to better connect with the specific communities they serve and meet their specific cultural and linguistic needs. For example, in an area of Connecticut with a large Portuguese-speaking immigrant population, brokers and assisters created fact sheets in Portuguese. Similarly, an assister in Colorado who serves the African American community developed informational materials that focus on the importance of obtaining health coverage to address some of the specific health problems faced by African Americans. Assisters also developed customized tip sheets and checklists to help ensure that individuals had all the information they needed to enroll when they started an application.

“…In one of our flyers that we created just to advertise our site, we would list things that would help; please bring… your Social Security card, your driver’s license, your last pay stub, citizenship status….” –Colorado Assister

Reaching large groups of people through events and local media.In all four study states, local community events such as fairs and sporting events served as valuable opportunities for states and assisters to efficiently reach large numbers of people. For example, in Washington, the Marketplace built a phone charging station at a popular music festival and stationed assisters by it to reach out to young adults. The state also sponsored roller derby, minor league hockey, and select league soccer and football games. In Kentucky, Marketplace and Medicaid officials and assisters attended festivals and events throughout the state, including the state fair, where they distributed information about new coverage options and encouraged people to enroll (See Box 1). States and assisters also created their own enrollment events. For example, in Kentucky, the Marketplace promoted a “Sign-up Saturday” event at local libraries, during which assisters helped people enroll using the library computers. Assisters in Colorado also hosted group enrollment appointments at local schools and libraries. Additionally, in some cases, assisters used local media outlets to reach large numbers of consumers. For example, some assisters in Kentucky participated in a weekly call-in show on the local news station, during which consumers could call in with questions about coverage options.

Box 1: Using the State Fair to Promote Outreach and Branding in Kentucky

The state fair in Kentucky has been a tradition for over 100 years. The fair is held in August at the Kentucky Exposition Center and attracts about 600,000 people annually. The 2013 state fair and other festivals and large sporting events across the state served as a key opportunity to provide information about new coverage options to large numbers of people. Marketplace and Medicaid officials and assisters hosted informational booths at these events to raise awareness about the new coverage options available through kynect and initiate one-on-one conversations with interested consumers (Figure 4). Officials and assisters found that starting with the question, “Do you know somebody that doesn’t have health insurance?” was a highly effective way to initiate conversations with individuals at these events. In addition, one successful way they engaged consumers at these events was by giving away reusable kynect shopping bags. These popular, colorful bags included the kynect logo and the caricatures that appeared in ads and other kynect marketing and have been credited with successfully raising awareness of kynect and initiating a marketing buzz. In total about 100,000 bags were given away during open enrollment with 22,000 given out in the 12 days of the 2013 state fair. Replicating the logo and characters on t-shirts and even hot air balloons made it difficult to go anywhere in the state without hearing about kynect.

“[The bags] were like gold. I mean they were just really pretty, colorful, and instead of us sitting there talking about healthcare, we’d say, ‘have you heard about kynect, let me tell you about kynect’ and then people would stop and listen, and ‘do you have health insurance,’…and if they said ‘yes, I have health insurance,’ ‘well do you have a child or do you have somebody that you know that doesn’t have?’ We made those connections and I think that that was one of our biggest success factors…. The state fair is getting ready to come up again in August. We’ll have a presence there. We’ll have a big booth.” –Kentucky Medicaid Official

Going mobile with outreach.The four study states employed a number of successful mobile outreach and enrollment strategies to reach uninsured consumers in places where they live, work, and play. Marketplace staff in Colorado and Kentucky travelled across their respective states in branded Marketplace RVs to promote coverage and get people enrolled (Figure 5). Washington and Colorado also deployed street outreach teams to do targeted outreach. Staff from the King County Public Health Department in Washington used tablets to find and collect information from uninsured homeless individuals and submitted Medicaid applications on their behalf. In Colorado, outreach street team members used tablets to collect contact information from young adults and Latinos in heavily populated areas. They then forwarded the information to the Marketplace staff, which would follow up with individuals about next steps to enroll. Consumers who spoke with a street team member also immediately received a thank you email with information on where to obtain enrollment assistance. The outreach street teams in Colorado spoke with over 64,000 people in more than 230 locations, including community events, shopping areas, theaters, gyms, coffee shops, and on streets with heavy foot traffic. In Connecticut, Marketplace staff conducted outreach at grocery stores and other retail outlets prior to open enrollment. Contact information was collected from those who stopped by booths in these locations, and individuals were subsequently sent information on enrollment assistance and enrollment events in their area. The state ultimately enrolled about 25 percent of those with whom they spoke at the retail outreach sites.

“So what we learned from the RV campaign was that when you did publicity, because we did press releases and we used our paid media channel, when we could promote the fact that we were going to be in certain communities for these opportunities…. people showed up, there were lines…” –Colorado Marketplace

Establishing walk-in enrollment sites.Marketplaces in Colorado and Connecticut provided additional opportunities for individuals to enroll in their communities by establishing walk-in enrollment sites. Access Health CT built storefronts in densely-populated urban areas to encourage people to walk in, collect information about coverage options, and obtain enrollment assistance from assisters or brokers. Data suggest that approximately 15,000 people visited the enrollment storefronts during open enrollment, and nearly 8,000 of them enrolled in coverage on the spot. Others obtained educational materials and often enrolled later. In March, Colorado opened five temporary walk-in enrollment sites in heavily populated areas that were staffed by Connect for Health Colorado and Medicaid agency staff, enrollment assisters, and insurance brokers. Nearly 3,000 people received help through these sites during the three weeks they were open.

Utilizing existing data to facilitate enrollment.Colorado, Connecticut, and Washington took up opportunities to get an early start on expanding Medicaid to adults prior to full implementation of the Medicaid expansion to adults in January. When the full Medicaid expansion took effect in January 2014, they automatically transitioned adults from these early expansion programs to the expansion. Colorado also enrolled more than 40,000 adults who were on the waitlist for the early expansion, which had limited enrollment. After enrollment began, Colorado also used data generated from the Connect for Health Colorado enrollment system to target outreach and enrollment efforts. Staff made outbound calls to individuals who started an account or application but did not complete enrollment to encourage them to enroll and refer them to local sources of enrollment assistance or a local enrollment event (See Box 2).

Box 2: Coordinating Targeted Outreach Campaigns with Local Enrollment Events in Colorado

In Colorado, Marketplace officials noted that one of their most successful outreach and enrollment initiatives was a series of targeted outbound campaigns from the Marketplace that directed individuals who had created a Marketplace account to local enrollment events. Over the course of open enrollment, the Marketplace generated lists of individuals who created an account but did not yet complete their enrollment into coverage. The Marketplace then conducted a series of outbound campaigns to these account holders to remind them to complete enrollment and direct them to sources of local assistance. When the Marketplace held an enrollment event in a specific community, it would reach out to account holders who had not completed in their enrollment in that community prior to the event to let them know about the event. They also used these campaigns to direct people to the temporary walk-in enrollment sites that were created in March and local enrollment events hosted by community partners and assisters. In total, the Marketplace made over 100,000 calls and sent over 500,000 emails to individuals who had created an account.

“What we would do is if we had an event that, say a broker group or an assistant site was having in a community, we would reach out directly to our account holders in that community and tell them about that… event. So, we did targeted outreach to our account holders and to potential customers to let them know about where they could get local assistance, when there was local assistance available.” –Colorado Marketplace Official

Engaging providers in outreach and enrollment efforts. Safety net providers were key partners in outreach and enrollment efforts since a large share of their patient populations are uninsured and eligible for the coverage expansions. Stakeholders noted that hospitals and community health centers played an important role in enrollment because they have existing relationships with their patients and their staff is often well-versed and experienced in communicating with their patients and with enrolling people into Medicaid and CHIP coverage. For example, in Kentucky, federally-qualified health centers conducted extensive “in-reach” to their uninsured patients to help enroll them in coverage. In addition, they helped enroll other uninsured individuals in the community. Similarly, a community health center in Washington reached out to uninsured patients in its service area by phone and email to encourage them to visit the clinic for help enrolling.

“The community health centers [sent letters] to their patient population that they knew were uninsured…they have this… audience that they know is uninsured… and they know who they are and they know how to reach them and they have staff who speak their language who are skilled in doing enrollments.” –Connecticut Assister

Consumer Assistance

Stakeholders in all four study states agreed that one of the most important elements of getting people successfully enrolled into coverage is personalized, one-on-one assistance provided through trusted individuals in the community. Within the study states, stakeholders identified a number of lessons learned about successful consumer assistance efforts including:

Recognizing that enrollment often requires time and education.Stakeholders noted that in order to develop trust and overcome misperceptions or fears about the ACA, individuals often require time and multiple touches from an assister. This was especially true among rural populations and immigrants. Since many newly enrolling consumers have limited experience with insurance, stakeholders indicated it is important to educate individuals about insurance and allow them time to familiarize themselves with what insurance is, what their costs would be, and various plan options. Given these consumer needs, successful enrollment of an individual or family sometimes requires multiple touches or visits with an assister.

“…Rarely does somebody walk in and an hour and a half later they walk out with a plan. It’s typically a series of many different appointments and hours spent.”–Colorado assister

.

“I think we acknowledged very early on… this… wasn’t going to be a big ad blitz and people were just going to miraculously sign up. People were going to really want to have their hand held…You can do some of that through the call center but I think people distinctively wanted to have the opportunity to do this in person.” –Connecticut Marketplace Official

.

“I think we achieved really good geographic distribution and then we also managed to really help serve specific targeted populations, which was also a goal…And then I was really happy to see that most of the state’s rural areas, they were all very much aware of the need for bilingual assistance and …looking at those vulnerable populations and rural areas as well.” –Colorado Marketplace official

Recruiting a diverse group of assisters with ties to local communities. The study states established extensive consumer assistance networks that often drew on existing networks of assistance, including those providing Medicaid and CHIP enrollment assistance, health clinics, community-based organizations, hospitals, and advocacy organizations. Several different types of paid and volunteer assisters supported outreach and enrollment efforts, including Navigators, In-Person Assisters, and Certified Application Counselors.1 Assisters had varied backgrounds and were able to provide personalized assistance to the communities they served. In Connecticut and Washington, assister organizations were required to have bilingual staff that spoke the predominant languages of the areas in which they worked and who identified with the communities’ culture. For example, in Connecticut, the Hispanic Health Council was the lead assistance organization in a region with a predominantly Hispanic population. Some assisters also said that because of their personal ties to the community, local organizations, schools, and other groups were often willing to work closely with them and sometimes offered resources, such as space and equipment, to support enrollment.

Developing strong relationships between assisters and brokers.In addition to enrollment assisters, insurance brokers played an important role in enrollment. Washington estimates that brokers enrolled over 100,000 people into coverage during open enrollment, including one in ten new Medicaid enrollments. In Kentucky, roughly 40 percent of enrollments into qualified health plans were facilitated by insurance brokers. The Marketplaces in all four states undertook significant efforts to engage brokers in enrollment and, despite some early fears and concerns among brokers, a large number of brokers in the four study states were certified and often worked collaboratively with assisters to enroll uninsured people. For example, in a hospital in Connecticut, brokers and enrollment assisters worked together closely, with the brokers referring Medicaid questions to the enrollment assisters and the assisters often relying on the brokers to share details of plans or private coverage options. Similarly, in Colorado, where over 1,500 brokers and agents were trained and certified by the Marketplace, stakeholders noted that having brokers and enrollment assisters attend enrollment events together strengthened their efforts. An assister could help an individual complete the application and then a broker could help that individual make a plan choice. Some assisters noted that brokers were particularly helpful in assisting individuals with specific health needs such as HIV and diabetes. Because they often had more familiarity with the plans, brokers were well-equipped to advise consumers about which drug formularies and services were covered in each plan.

“Agents felt very threatened about it, so very early on, both the Commissioner of Insurance and our folks assured agents that they’re going to have a role and they’re going to have a very important role. And so when we set up the advisory broad, we established several subcommittees and one of them was a subcommittee called Agents and Navigators. …The idea was that we were going to put the two competing forces…together and see if we couldn’t work out some kind of agreed to relationship.” –Kentucky Marketplace Official

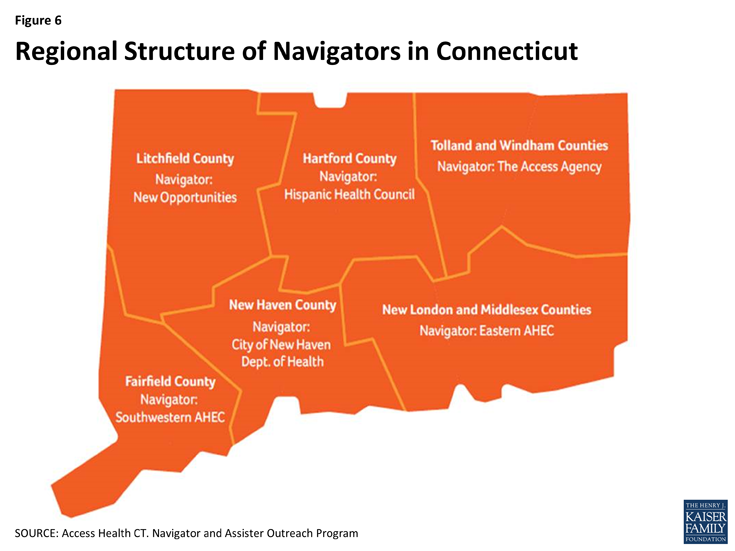

Coordinating assistance through a regional hub and spoke structure.All four states utilized a regionally-based hub and spoke structure to organize and coordinate assister activities. Within this model, several lead regional organizations helped organize and coordinate activities of assisters in their area, disseminate updates and information from the state to assisters, and provided feedback on implementation to the state. For example, Access Health CT divided the state into six regions and assigned Navigator organizations to oversee the work of assisters in each area (Figure 6). In some states, broader coalitions of stakeholders also helped coordinate and organize activities. For example, in Louisville, the local Board of Health established an outreach and enrollment coalition that coordinated efforts, shared best practices, and provided feedback on experiences in the field to the state. Similarly, in Colorado, an existing statewide coalition served as a liaison between on-the-ground assisters and the Medicaid agency and Marketplace. The coalition was valuable for sharing information between assisters and state officials to help address issues that arose during open enrollment. Assisters in Kentucky and Connecticut also used shared online calendars to indicate where and when they were planning events, which helped prevent gaps and overlaps in outreach and enrollment efforts.

“We had a lead organization run point on that region of the state. And within those lead organizations that were selected for the respective regions…they had to demonstrate how they were going to set up a network that was going to be able to help them reach goals as it related to enrollment and assistance and outreach…and it had to include outreach [in] different languages, different backgrounds, depending on where they were…There was a lot of creativity provided by these lead organizations and they did a really good job.”

–Washington Marketplace Official

Providing readily available support to consumer assisters. All four study states established resources for assisters and brokers to obtain support when they had questions or needed assistance while helping a consumer. Assisters had dedicated telephone lines to reach call center staff, which helped reduce long waits when they needed support. Colorado and Connecticut had several Marketplace staff members dedicated to addressing assister needs and questions. At the launch of open enrollment, the staff held daily phone calls with assisters to provide updated information on processes and obtain feedback, which was used to continually improve processes and systems. The staff was also readily available by phone or email to help assisters with complex cases, website problems, and other issues. In Connecticut, the Marketplace placed staff, called Navigator Coordinators, in each of the regional lead consumer assistance organizations. These coordinators had greater access to the eligibility system than Navigators or assisters and could help troubleshoot technical problems. Marketplace staff in Connecticut also organized monthly meetings of regionally-based assisters to share best practices, coordinate events, and discuss strategies for reaching particular populations. In Washington, the Marketplace sent weekly emails to lead assistance organizations to communicate key lessons, responses to questions, and the status of system fixes and also hosted weekly calls. Kentucky also maintained close and regular communication with assisters to both share updates and information and receive feedback on implementation.

“I really love the people that work with Assistance Network of Connect for Health Colorado; they are really responsive, they are really open, and they know their stuff…. During open enrollment they hosted weekly support calls with all the health coverage guides and application counselors and… whenever somebody had a question or an issue it got resolved right then and… whenever I send them an email… it always gets responded even when if it’s.. 8 pm or 10 pm….” –Colorado Advocate

Expanding call center capacity and creating tiered assistance levels.Stakeholders in all four study states noted that their Marketplace and Medicaid call centers were an important resource for consumers. Because of early technological challenges with the enrollment portals, the call centers became a primary resource to answer consumer questions, take phone applications, and work through glitches. Consumer demand for the call centers exceeded expectations early during open enrollment. In Washington, for example, the Marketplace call center anticipated receiving about 2,500 calls per day but averaged between 8,000 and 10,000 calls daily. The states enhanced capacity to respond to this increased demand by training and hiring more staff, contracting with additional vendors, extending call center hours, and creating tiered levels of assistance so calls could be directed based on what type of assistance a caller was seeking. For example, consumers seeking information would be routed to different staff than those attempting to complete enrollment via the phone.

“…Nobody, I mean nobody anticipated the demand or volume of calls or even the length of the calls.”–Kentucky Marketplace Official

Systems and Operations

The study states took different approaches to building their enrollment systems and faced varying degrees of early technological challenges. The effectiveness of the study states’ enrollment systems and the states’ ability to quickly respond to technological challenges also contributed to their enrollment successes. In addition, stakeholders identified certain aspects of state policies and program operations that helped promote coverage efforts. Elements highlighted by stakeholders included:

Developing close working relationships between staff and contractors and setting realistic expectations for the system builds. Stakeholders stressed that close collaboration among policy staff, IT systems staff, and contractors were vital during both the initial builds of the system and on an ongoing basis to manage systems and quickly resolve problems. Connecticut had Marketplace staff dedicated to working with contractors to monitor their work and track their progress. In all four states, contactors were co-located on site with state policy and IT staff to facilitate close and constant communication. Moreover, stakeholders stressed the importance of setting reasonable expectations for system capabilities, recognizing that enhanced features can continue to be added over time. For example, Access Health CT limited the extent of features it planned to include halfway through its system build to focus on core functions.

“It’s an excellent relationship. I mean [the IT contractor] is right here in this building…they got 45 staff here that work with our staff…and we’re all located here in this building, which is very important so if we have an issue… we just go down the hall to see what’s going on, and we meet with them regularly, so they’ve been a great partner.” –Kentucky Marketplace official

.

“Creating disciplined processes [was important]. So figuring out what you can do well and what you can’t….For example, in January of 2013, we rolled back by 30 percent what we had originally asked [the contractor] to build for us in the fall of 2012. That was the most important decision we made. If we had kept with our original plan, I’m not sure we would have been up and running.

–Connecticut Marketplace official

Building effective enrollment systems with consumer-friendly features. Kentucky and Washington built single, integrated eligibility systems for Medicaid and Marketplace coverage. This allowed for a streamlined enrollment process that did not require any transfers of applications between programs. Moreover, consumers only receive a single notice of their determination rather than separate notices from each program, which minimized confusion. Stakeholders indicated that, while these systems faced some early technological glitches, and the states continue to work through problems, they worked well for most consumers, particularly toward the end of open enrollment. The systems are also able to make real-time determinations for most cases and can handle complex situations in which members of a family may be eligible for different types of coverage. Colorado and Connecticut maintained two separate systems for Medicaid and Marketplace coverage and faced some challenges coordinating enrollment between the two systems. However, as described below, through workarounds and ongoing system improvements, they were still able to enroll people successfully. Stakeholders also highlighted certain features of systems that proved particularly valuable. For example, in Kentucky and Connecticut, stakeholders highlighted a pre-screen feature that allows consumers to anonymously shop for coverage after answering a few quick questions, as well as the ability to electronically upload documentation when it is required.

“It’s a one stop shop. You know, it takes maybe 30 to 45 minutes. You enter your information. If you’re Medicaid eligible, you pick a Medicaid managed care organization. If you’re QHP eligible, you pick a qualified health plan. So, certainly that one stop shop streamlined application process I think really attributed to our success.” –Kentucky Marketplace Official

Implementing workarounds and incremental fixes to quickly address enrollment system problems. Stakeholders noted that although all of the study states faced early problems with their enrollment systems, they implemented workarounds and solutions that allowed them to continue to enroll people. For example, in Washington, assisters used paper applications during the early part of open enrollment while the system was experiencing problems. Similarly, in Colorado, consumers were redirected to the call center to complete applications during the initial launch of open enrollment as full functionality for the Marketplace system was still being established. Connecticut is still continuing to work to improve the process to transfer applications from the Marketplace to Medicaid, but in the interim is sending notifications to providers advising them that individuals determined eligible for Medicaid through the Marketplace can access services before they receive a benefit card. All states also created workarounds to address system glitches that affected some immigrant families, people formerly involved in the criminal justice system, and those in other complex family situations. Beyond implementing workarounds, the states made ongoing improvements to their systems throughout open enrollment to fix problems as they were identified. For example, the Medicaid agency in Colorado established a flexible contract with its vendor that provided dedicated time for system fixes to be implemented each week.

“One thing that I think [the Medicaid enrollment system] did really well is that, when they realized that there was some sort of… problem or barrier for people, they changed things.” –Colorado Advocate

Using data and feedback loops to identify and respond to needs as they were identified.Medicaid and Marketplace officials in the study states received frequent enrollment data updates that helped them identify any problems with their enrollment systems and target outreach and enrollment efforts. For example, in Connecticut, the Marketplace shared regular data updates on enrollment by zip code with regionally-based assisters to help them target their community-based outreach efforts. Similarly, the study states obtained regular feedback from assisters and community-based organizations and quickly responded to any implementation issues they identified. For example, Colorado launched a statewide brand awareness campaign in English and Spanish, but learned that the Spanish messaging was not resonating with consumers. In response, the Marketplace quickly organized a stakeholder group meeting and brought in the translation firm to create revised materials that would better connect with the Spanish-speaking community.

“…We had staff… that monitored the system. We had what we called our command center…where we would watch all the statistics so, how many applications, is the system up, what’s our capacity? We even monitored the call center at the command center…. The first of order of business was to determine if there is some kind of a system error that’s going on here; is this a user error that’s going on so, and as we got complaints about things…you build up this tracking system or this ability to see what kind of changes need to be made.”

–Kentucky Marketplace official

Collaboration and Leadership

Promoting coverage efforts through strong leadership. Stakeholders in the study states noted that there was strong leadership for their coverage efforts. For example, in Kentucky, the Governor made successful implementation of the coverage expansions a priority, and this leadership carried down through state officials. Stakeholders reported that Marketplace and Medicaid officials were highly engaged and personally committed to achieving success and were often present at outreach and enrollment events. Similarly, stakeholders in Colorado and Washington noted that implementation of the ACA built on earlier state health reform efforts that created streamlined Medicaid enrollment policies and helped establish a culture of coverage in the state.

Collaborating with key stakeholders. In addition to strong leadership, the study states cited close collaboration between stakeholders as a key contributor to their success. In Kentucky, all state agencies involved in health reform implementation, including Medicaid, the Marketplace, and the Department of Insurance are peer agencies housed within the Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services. Stakeholders indicated that this structure helped promote strong working relationships among the agencies and that they worked hand-in-hand throughout planning and implementation of the coverage expansions. Stakeholders in Colorado also indicated that close collaboration between the Medicaid agency, Marketplace, and Department of Insurance was important and noted that an interdepartmental website was developed to share information with consumers. In addition, in all four states, advocates and community-based organizations were engaged early and often throughout planning processes and implementation. For example, in 2012, Connecticut began a series of town hall meetings called “Healthy Chats” and invited advocates, insurance carriers, and other relevant stakeholders to learn about progress in implementation and share feedback.

“We have weekly stakeholder meetings over at [the Marketplace]. It gets us all in a room and it’s a lot harder to fuss when you’re looking at somebody because we’re all peer agencies. We’re all under the same umbrella but it’s easy to get frustrated. If you all get in a room once a week it’s hard to stay frustrated because you just ask the questions and work through things. I think they’ve been very effective.” –Kentucky Medicaid Official

.

“I would say the foundations of our success from an outreach, communications, and marketing standpoint are that we had a strong foundation of working with stakeholders and we continued to be committed to that process to today. So every policy decision that the Board made, we had stakeholder discussions…before they made their decisions. So from a policy prospective, from an operational prospective, but also from an outreach and communications prospective they were at the table.”

–Colorado Marketplace Official