An Early Look at Implementation of Medicaid Work Requirements in Arkansas

Introduction

Arkansas is the first state to implement a Section 1115 waiver that conditions Medicaid eligibility on meeting work and reporting requirements.1 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) approved these new requirements as an amendment to Arkansas’ existing Medicaid expansion waiver, now called Arkansas Works, on March 5, 2018.2 Arkansas’s original waiver allows it to use Medicaid funds as premium assistance to purchase coverage for most expansion enrollees in Marketplace qualified health plans, a model known as the “private option,”3 instead of implementing a traditional Medicaid expansion.4 Medicaid expansion in Arkansas increased eligibility for parents from 17% to 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL, $3,533 to $28,676 per year for a family of 3 in 2018), and covered childless adults for the first time, up to 138% FPL ($16,753 per year for an individual in 2018), contributing to a substantial reduction in the state’s uninsured rate.5

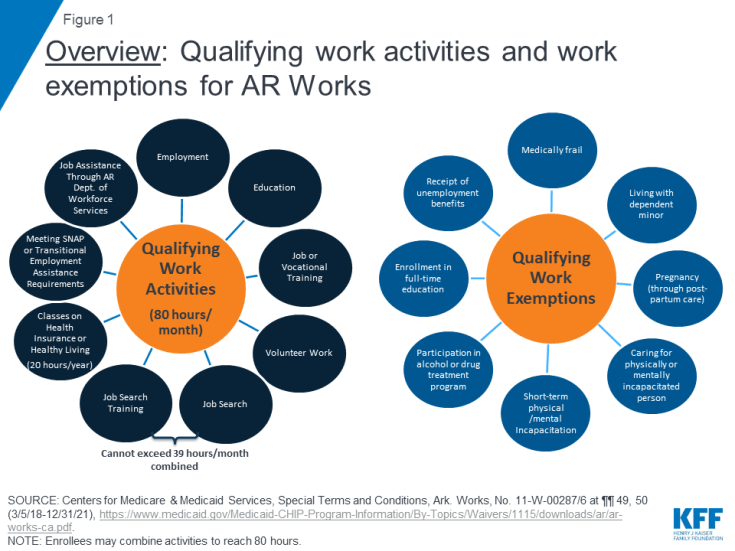

Under the waiver amendment, Arkansas is requiring most Medicaid expansion enrollees6 to complete 80 hours of work or other qualifying activities per month for at least 10 months per calendar year, unless exempt, and to report their work or exemption status using an online portal7 (Figure 1). The new requirements are being phased in, beginning in June 2018. The first case closures for failure to meet the requirements for three months were effective in September 2018.8 A separate brief provides an overview of the monthly data released by the state. State data show that, as of September 9, more than 4,300 enrollees lost Medicaid coverage as a result of the new work and reporting requirements, and another 5,000 were at risk of losing coverage with another month of non-compliance.9 While implementation has continued to date, three Arkansas Medicaid enrollees have filed a federal lawsuit challenging CMS’s approval of the waiver amendment.10

This brief analyzes the early experience with implementation of work and reporting requirements in Arkansas, based on publicly available data and other written materials, as well as targeted interviews with state officials, health plans, providers, and beneficiary advocates conducted in August and September 2018. This brief examines three key questions and then draws on findings from Arkansas to help inform policymakers in other states moving forward with similar requirements. Key findings explore answers to three key questions: (1) What was needed to get started with early implementation of the new work and reporting requirements? (2) What are the challenges related to ongoing implementation of the new work and reporting requirements? (3) What are the consequences of coverage loss?

Key Findings

1. What was needed to get started with early implementation of the new work and reporting requirements?

To get started with the implementation of the new requirements, the state needed to conduct a substantial amount of outreach and education, and enrollees needed to create an online account to be able to report exemptions or work activities. This section discusses the challenges in each of these initial steps.

Outreach and Education

Despite a robust outreach campaign conducted by the state, health plans, providers, and beneficiary advocates, many enrollees have not been successfully contacted. There was consensus across interviewees that many enrollees are not aware of and do not understand the new requirements, despite the acknowledgement that the state has devoted considerable efforts to developing outreach materials, and health plans have dedicated staff to educating enrollees and helping them comply with the new requirements. The state and health plans are using multiple means of contacting enrollees, including making outbound calls; sending mailings,11 texts, and emails; posting information and videos online;12 using television, radio, and print media; and educating providers, including doctors and pharmacists, and community-based organizations.13 While health plans received lists of enrollees who were subject to the new requirements and updates on compliance to help target outreach, at least some providers did not have similar information to conduct outreach or target help to patients at the highest risk of losing coverage. Outreach by the health plans has required investments in materials and staff. Although the state was developing implementation plans prior to the approval of the waiver, there was a short time from waiver approval to implementation (March 5 to June 1) for the state to conduct initial outreach and education efforts.

Telephone calls have been a focus of state and health plan outreach efforts, but their effectiveness is limited. Enrollees may be hard to reach by phone for a variety of reasons. One health plan noted that over half of the enrollees on their targeted list do not have a phone number included in state data, others may have an incorrect phone number listed, and most of the remaining enrollees do not pick up the phone or respond to voicemail messages. One safety net provider observed that many enrollees have pre-paid government subsidized phones, for which the number resets every time the minutes run out, resulting in a new phone number every month or two. The state has contracted with the Arkansas Foundation for Medical Care (AFMC) to make outbound calls to educate enrollees about the new requirements,14 but AFMC is only required to contact 30% of existing enrollees15 and 40% of newly approved enrollees,16 with contact defined as “a minimum of two attempts by a live agent to contact beneficiaries by phone when a phone number is available.”17 State data on outreach efforts show that AFMC made over 39,000 calls to just under 12,000 enrollees in May, and over 47,000 calls to about 9,000 enrollees in June.18

Social media and online videos are likely to have a limited reach among enrollees who may lack access to computers or the internet. Enrollees are unlikely to look to social media for information about new program requirements from the state. Similar to national data, state-specific data show that nearly one in three (31%) of those non-exempt and not working have no access to the internet.19 Outreach efforts at the local level, in person or through word of mouth from trusted sources, could be more effective than social media. In addition, early in implementation, some internet links provided in the state’s online informational videos were broken.20

Notices sent by the state may be confusing, and outreach efforts may not sufficiently account for low literacy and lack of English proficiency among enrollees. Advocates and providers described written notices sent by the state to enrollees as confusing, and complete information was spread across multiple notices. For example, the first notice provided to enrollees who are newly subject to the work requirement instructs them to report their work activities by the fifth of the following month, unless they receive another separate notice indicating that they are exempt from reporting.21 In addition, low literacy and lack of English proficiency could affect outreach and understanding of new requirements. In areas of the state with a large Hispanic population, not receiving written notices in Spanish was a concern. As a result of the way the private option is structured, another interviewee noted that many expansion enrollees are not used to regularly looking for or exchanging information with the state because their only contact with the state was for their initial eligibility determination and renewal, while they have more frequent contact with their health plans.

Setting up online accounts

The process for enrollees to set up an online account for reporting is complicated. Beneficiary advocates and providers described their own confusion with trying to understand the various steps required to create and link online accounts:

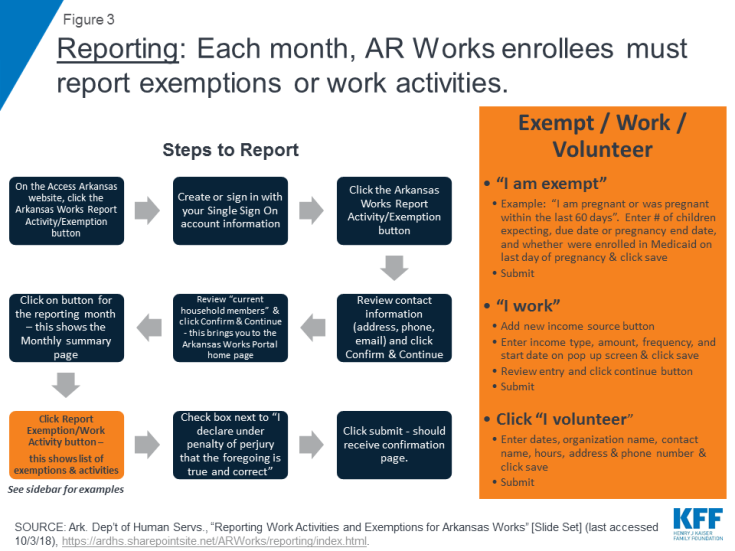

- First, enrollees must create an “Access Arkansas Single Sign-On” account, an eight-step process that includes 5 security questions.22

- Next, enrollees must link their Single Sign On account to their health care coverage, which involves three additional steps once they are logged into their Single Sign On account23 (Figure 2). Linking the account also requires enrollees to have received a written notice by mail or email with a reference number that they must enter online.24

Figure 2: Getting started: Steps to create and link online accounts for reporting work activities and exemptions for AR Works

Lack of computer literacy and internet access among enrollees are barriers to setting up the online accounts and complying with the reporting requirements. Arkansas’ waiver is unique because it also includes an online reporting requirement, for which the state designed an online portal.25 All enrollees must have an email address that they use to create an online account, which they then must link to their health coverage account even if they believe that they are exempt from the work requirement. Enrollees must then report their monthly work activities or work exemption status, attesting to the information’s accuracy, in the online portal by the fifth of the following month, unless they qualify for a reporting exemption. Reporting by phone, by mail or in person is not permitted.26 Many enrollees only have internet access via a cell phone, and some interviewees were concerned that the portal was not mobile friendly. Other enrollees have to rely on internet access through public computers such as those at a library. The state has determined that 92% of the enrollees expected to be affected by the new requirements live within 10 miles of a public internet access site.27 However, traveling that distance, especially on a regular basis, could still be challenging for individuals without a car, as much of the state lacks public transportation.

Providers, health plans and beneficiary advocates all agreed that a number of enrollees need individualized help to walk through the complex account setup and reporting process, yet few enrollees are using registered reporters. Many expansion enrollees needed individualized help creating email addresses and enrolling in coverage online during Medicaid expansion implementation. For the work requirement, the state created a “registered reporter” program that allows enrollees to designate a third party to create their online accounts and access the portal to do their reporting.28 Health plans and some providers have designated staff to serve as registered reporters. However, few enrollees are using registered reporters, in large part because it has been hard to reach enrollees to educate them about the new requirements. Some providers noted that there were no funds provided for training and education about the portal, leaving many with challenges in helping enrollees navigate the new work and reporting requirements. Nevertheless, at least some safety net providers have devoted their own resources to provide laptops or iPads in clinic waiting areas for their patients to use for reporting.

Non-compliance with the new requirements to date is attributed to lack of knowledge about the complex new requirements. Of the 60,012 people who were subject to the new requirements in August 2018, 27% (or more than 16,000 people) did not report 80 hours of qualifying work activities.29 Failure to report work activities could mean that the enrollees did not create and link the online accounts required to enable them to report or experienced difficulty accessing or navigating the online portal. Additional research about those individuals who do not report can help inform future outreach and education strategies that may be more effective in contacting individuals who may be unaware of the new requirements or in areas of the state that are harder to reach.

2. What are the challenges related to ongoing implementation of the new requirements?

Data Sharing

The state is using data matching to exempt about two-thirds of enrollees from the reporting requirements. Most of these enrollees fell into four categories: those who were already working at least 80 hours per month (46%), followed by those currently meeting or exempt from Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, previously known as food stamps) employment and training (E&T) requirements (18%),30 those with a dependent child in the household (13%), and those who have been identified as medically frail (15%).31 Most exempt enrollees were identified as such through the state data matching process and should have received a notice indicating that they were subject to the work requirement but exempt from the reporting requirement. Another 5% (2,247) of the exempt enrollees reported an exemption since receiving a notice that they were subject to the work requirement.32

Data sharing across state agencies and health plans is generally working well. The state reported early and frequent collaboration among the Medicaid, SNAP, and TANF (Transitional Assistance for Needy Families cash assistance, called Transitional Employment Assistance in Arkansas) programs, as well as between the state Medicaid agency (under the Department of Human Services, or DHS) and Department of Workforce Services (DWS) to implement the new requirements. DHS and DWS were able to use federal TANF funds to transfer lists of Arkansas Works enrollees from DHS to DWS computer systems in a new TANF case management system already in development. The Arkansas Works program, SNAP, and the TANF programs resided in three separate eligibility systems operated by Arkansas DHS;33 implementation of a daily file exchange across those systems to update exemption and compliance information across programs without manual intervention has gone smoothly. A regular data file transfer across agencies and from the state to health plans is also in place.

Online Reporting

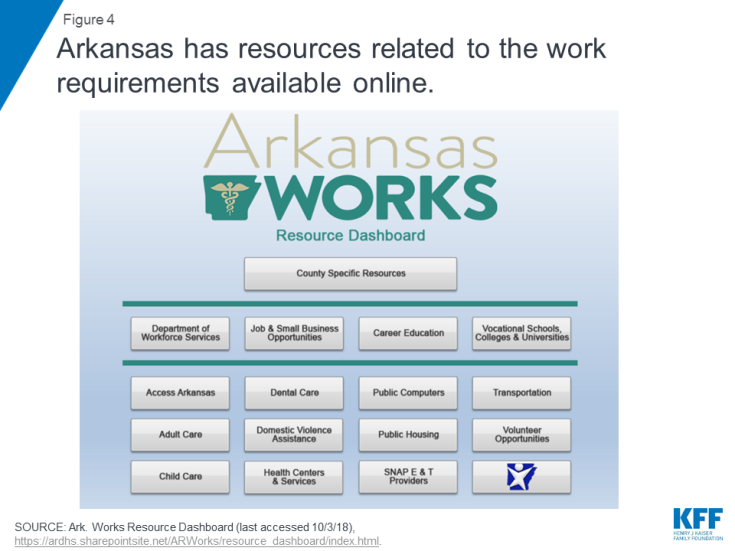

Enrollee reporting of exemptions or work activities requires multiple steps. Under the waiver, enrollees must report a month’s work activities or exemptions by the fifth of the following month. They lose coverage for the rest of the calendar year if they fail to meet the work and reporting requirements for any three months. Enrollees must enter the required information to complete their online reporting each month, a process that includes at least 13 separate steps to report work hours, with additional steps required if beneficiaries are reporting hours for more than one job.34 There are 11 separate steps to report volunteer hours or to report an exemption based on pregnancy35 (Figure 3).

Program rules about the frequency of exemption reporting and hour limits for certain activities are complex. Some online reporting is required more or less frequently than monthly. For example, students need to report full-time status weekly for four consecutive weeks before they qualify for a six-month exemption from reporting.36 Other students continue to report weekly.37 Some exemptions, such as caring for an incapacitated person, short-term incapacity, and participation in alcohol or drug treatment, must be reported every two months, while others, such as receiving unemployment benefits or full-time participation in school or vocational training, must be reported every six months.38 There are also complicated rules about how many hours of various activities can count toward the 80-hour monthly requirement. For example, beneficiaries are limited to 39 hours per month of job search and job search training activities and 20 hours per year of health education class hours.39

Some activities have different conversions to countable hours. For example, for job search activities, each job contact counts as three work activity hours, while each hour of job search training counts as one work activity hour. Each credit hour for college or vocational school courses counts as 2.5 work activity hours. An hour of high school or ESL instruction counts as 2.5 work activity hours, while an hour of GED, basic skills, or literacy instruction counts as two work activity hours. One hour of “occupational training instruction” counts as two work activity hours, while an hour of “unpaid job training” counts as one work activity hour.40 The online portal does these calculations, but enrollees need to be aware of the rules or else they may go to report and fall short of the 80 qualifying hours required if they have devoted too many hours to job search or job search training.

Enrollees are unaware that they could be asked to verify their exemption status in the future. Enrollees do not have to provide documentation to verify their exemption status when reporting an exemption in the online portal, which helps to simplify the exemption process. Still, stakeholders worried about enrollees being unable to produce documentation if asked to do so months later as part of a state quality assurance check41 and therefore retroactively losing an exemption.

In September 2018, the first month that individuals could lose coverage for failure to report work or exemptions, there were technical issues that interfered with online reporting. There was a state computer outage on September 5, the deadline to report hours for August, and the first time that enrollees were at risk of losing coverage for three months of non-compliance. In response, the state is allowing enrollees who experienced difficulty accessing the portal to request a good cause exemption for late August reporting by October 5. Internet and cell phone connectivity, especially in rural areas, can be slow and unreliable, which can translate to problems with reporting online. One interviewee cited multiple examples of enrollees having difficulty linking their online accounts because the reference number provided in the notice did not work or they did not receive the notice with the reference number.

exemption processes

Enrollees who may qualify for exemptions that are not identified via the state data match may fall through the cracks. Exemptions unlikely to be identified through the state data match include caring for an incapacitated person or experiencing a short-term incapacity, pregnancy, participation in an alcohol or drug treatment program, and full-time students. A health plan reported that it had identified significant overlap between its enrollees who are subject to the work requirement and enrollees for whom it provides case management. Case management targets enrollees who need “additional intervention” to manage chronic conditions and find resources to address basic needs such as food insecurity, transportation and shelter. Given these criteria, these enrollees are likely to face barriers to compliance with the new requirements and/or the exemption process on their own due to their need for additional support. While health plans may have claims data or other information showing that an enrollee may be medically unable to work, the plans cannot initiate that determination. Instead, the enrollee must pursue a medically frail designation. Some interviewees expressed concern about enrollees’ ability to understand their potential qualification for exemption as well as navigation of that process, especially among those with mental health needs. The requirements to update certain exemptions at different intervals may also confuse enrollees and lead to their failure to update exemption information timely, which would result in non-compliance and coverage losses. To date, there have been few requests for reasonable accommodations by people with disabilities, which may reflect lack of knowledge among enrollees.

The good cause policies and process have only been recently finalized, resulting in confusion about how to make such requests. The availability of a good cause hardship exception for failing to meet the new requirements is explained in the notice informing enrollees that their case is closed for 3 months of non-compliance but not in earlier notices.42 Good cause must be requested online (but not through the portal, as exemptions are) and can be separately determined, both for not working and for not reporting timely.43 While this process is important for those who could lose coverage, there was some concern about state capacity to process a large number of good cause requests given past challenges with application and renewal processing.44 According to the state’s monitoring plan, good cause approval and denial notices are being generated manually until that functionality is added to the eligibility IT system.45 As of August 2018, 55 enrollees had requested good cause, and the state had granted 45 of those requests.46

Access to work and work supports

State data so far suggest that a small share of those who are meeting the work and reporting requirements are doing so by engaging in activities beyond those required to meet SNAP requirements. The data do not indicate whether these enrollees started working in response to the new requirements. They could have been already engaged in work or another activity without the state having this information. This group represents a small share of enrollees compared to the more than 4,300 who lost Medicaid coverage due to failure to comply with work or reporting requirements. It is unclear why individuals reporting SNAP compliance through the portal are not included in the state data match that would have exempted them from the reporting requirements. The data do not separate out those who are newly working due to the requirements.47

Transportation is a major barrier to work throughout the state and especially in rural areas.48 In many communities, there is “no effective alternative” to having a car for transportation. Most of the state has no public transportation system. Lack of transportation can be a barrier to getting to work or accessing education and training supports. Forty-three of 75 Arkansas counties lack physical DWS workforce services locations, and 25 counties lack physical locations for SNAP employment and training providers at the time of initial work requirement implementation.49 The state indicated that SNAP enrollees can be reimbursed for transportation costs or go to a local office for a conference call if a SNAP E&T provider is not in the county where they live. DWS offers services online, but these require individuals to have internet access.

While the state reports a low unemployment rate and robust economy, there are few jobs in rural areas of the state and for people with low educational levels. Many jobs available to enrollees are seasonal, such as construction or agricultural work. DWS reports about 65,000 to 67,000 openings currently in its job bank, with a “wide range of jobs” available, such as advanced manufacturing, health services, construction, and professional services. Still, the state acknowledges challenges in rural areas that are primarily agricultural, lack industry, and require a car for transportation.

Relatively few enrollees have sought DWS services since the work requirement took effect. Health plan case managers and AFMC outreach calls are making referrals to job training, resume assistance and other DWS services, noting a lack of awareness among enrollees about these services. Medicaid notices to enrollees about the work requirement include information about how to contact DWS for free job search help.50 The state’s monitoring plan indicates that DWS will offer career assessment, job search assistance and training referrals “as appropriate” to enrollees subject to the work requirement.51 Enrollees will have access to DWS career readiness certifications, resume assistance, “universal job services,” and screeners to determine program eligibility and computer literacy. They can also receive assessments for high-demand occupations based on current skills and abilities as well as for identification of barriers to work.52 Once assigned to a DWS case manager, DWS will track enrollees through monthly follow-ups for six months after they get a job to help ensure that they remain employed.

If substantial numbers of enrollees subject to the new requirement seek DWS services, there could be a shortage in DWS caseworkers and work supports without additional funding, and Medicaid funds cannot be used to pay for work supports.53 DWS reports having sufficient staff to serve enrollees who are presently seeking its services.54 However, no new money has been provided for work supports, and access to DWS- Workforce Innovation & Opportunity Act (WIOA) funded education, training, and apprenticeship programs depends on funding and availability.55 The state reports that it has absorbed a 7% cut in federal workforce training funds, with current DWS caseloads at about 135 clients per counselor. Current legislation provides $112.5 million less in federal funding for job training services nationwide for FY 2019 than FY 2018.56 DWS originally received identification of 35,000 Arkansas Works enrollees, but many were subsequently determined to be exempt from the new requirements, leaving DWS with about 15,000 enrollees who may be in need of jobs, training, or other services in order to keep their Medicaid coverage.

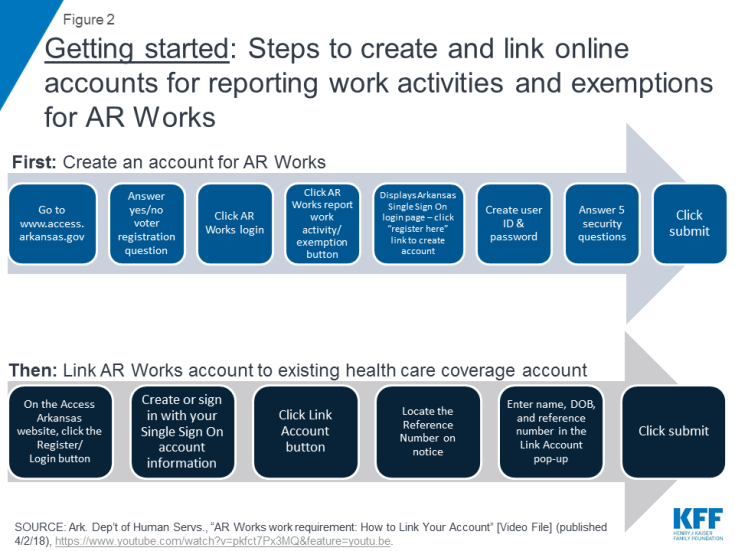

The state has a good deal of information related to the work requirement online, but enrollees need internet access, and key details about volunteer or training opportunities are often missing. For example, the Arkansas Works Resource Dashboard maintained by the state includes a list of public computers and county-level resource guides with various resources for employment, volunteering, education, “quality of life” (e.g., food banks and shelters), and county agencies57 (Figure 4). Enrollees must have internet access to view this information, and the listings are limited to the organization name and phone number and do not identify specific slots or available volunteer opportunities. Another state website, ARJobLink, does list job openings, but this information is available from the DWS website and not directly from the resource dashboard.58 Similarly, information about how to access the health education classes that can count toward the work requirement for up to 20 hours per year is not clear. Some information about the classes appears on the AFMC website,59 but it is unclear if enrollees must pre-register online to attend.

Stakeholders questioned whether meeting the requirement through volunteer activities was a viable option. Without a more structured approach to engage and train volunteer organizations in a systemic way, finding volunteer opportunities depends largely on social connections and supports. This dependence could unfairly penalize some enrollees, especially those in rural communities where the only volunteer opportunity may be a local church where they are not a member.

3. What are the consequences of coverage loss?

As of September 9, 2018, more than 4,300 cases were closed due to three months of non-compliance with the new work and reporting requirements. Another 5,000 enrollees were at risk of losing coverage in October, according to state data.60

Enrollees could experience gaps in coverage even if they ultimately meet the reporting requirement. The state is sending notices to individuals who are non-compliant for two months, indicating that their cases will be closed on the last day of that month even though they have until the fifth of the next month to meet the reporting requirements. For example, individuals who were non-compliant for June and July were notified in letters dated August 6 that their cases would be closed on August 31, even though they would have until September 5 to report exemptions or work activities for August.61 If individuals do report by the fifth of the month, the state would reinstate their coverage. However, this process could result in a coverage gap from September 1 to September 5. Individuals who try to see a doctor or fill a prescription during this period would fall into that coverage gap and have to pay out of pocket or delay or forego care until their coverage is reinstated. This process can also create confusion about compliance and reporting deadlines.

Gaps in care and increases in uncompensated care costs are among top concerns if enrollees lose coverage. Health plans note that stable enrollment is critical to providing ongoing care, particularly for enrollees with mental health or chronic conditions, and to managing risk as healthier individuals are disenrolled. While safety net clinics continue to provide primary care services to the uninsured, they do not offer prescription drugs or specialist care needed to manage chronic physical and mental health conditions, which could result in more potentially avoidable hospitalizations and mental health crisis services. Plans and providers expressed concern that individuals who lose coverage and become uninsured will still seek care and that providers will see increased uncompensated care costs. Some providers worried that, because coverage increases under the expansion led to increased diagnosis and treatment of chronic conditions such as diabetes and high blood pressure, coverage loss could create higher uncompensated care costs than before the expansion. Expansion coverage had brought better financial stability for providers, and many thought that they would not be able to absorb increased uncompensated care costs.

Disenrollment of healthier enrollees could have implications for the health plan risk pool that would result in higher premiums. Arkansas had already experienced a significant drop in Medicaid enrollment prior to the implementation of the new work requirements.62 Additional coverage losses could exacerbate issues resulting from the changing case mix of enrollees. If healthier enrollees who have less costly and complex conditions lose coverage, premiums could increase for the enrollees who remain covered. The state pays these premiums for Medicaid enrollees, but Medicaid enrollment has been a stabilizing factor for the Marketplace, in which qualified health plan (QHP) enrollment has consisted of 80% Medicaid enrollees and 20% Marketplace enrollees.63 Changes in the case mix could thus increase premiums for all QHP enrollees. In addition, one plan indicated that capitation rates had already been adjusted upward to account for increased costs due to administration of the work requirements.

More data could be available through the formal waiver evaluation, but details about the evaluation plan are not yet publicly available. The most recent quarterly report, for the period ending June 30, 2018, indicates that the state is seeking a vendor to evaluate the amended waiver.64 The waiver terms and conditions required the state to submit a draft evaluation plan to CMS within 120 days of CMS approval (by July 3, 2018). The state indicated that CMS extended this deadline on July 3 and that the state subsequently submitted the draft evaluation plan. The state must submit a final evaluation design to CMS within 60 days after receiving any CMS comments and post the final design to the state website within 30 days of CMS approval.65 To date, monthly state data about compliance with the new requirements have provided key information to understand early effects of these new provisions.

Looking Ahead

Research and interviews align in the acknowledgement that work for enrollees who are able to do so is a laudable goal; however, the waiver design that ties compliance to coverage, requires monthly online reporting and provides no additional resources for work supports could lead to unintended consequences.

Implementation is complex and may result in increased administrative costs for the state and other stakeholders. Implementation requires months of planning to draft and send notices, conduct beneficiary outreach and education, update IT systems and coordinate across multiple state agencies, health plans and providers. Without additional resources, it is difficult to administer complex changes. Some providers and plans may also face increased costs conducting outreach and helping enrollees comply with new requirements.

Outreach is difficult, especially in rural areas and for vulnerable populations. Many enrollees do not have stable addresses, phone numbers or access to email and internet. These barriers could leave many enrollees unaware of the new requirements, as typical forms of outreach, including mail, telephone calls, emails, and social media, may not be effective. Some of these challenges may particularly affect rural areas.

Many enrollees who remain eligible could lose coverage if they fail to navigate the process to verify work status or qualify for an exemption. The model in Arkansas that relies solely on reporting work or exemptions through an online portal may be unique, but research shows generally more disenrollment among individuals who remain eligible but lose coverage due to new administrative burdens or red tape than among those who lose eligibility due to failure to meet new work requirements.66 The limitations of requiring enrollees only to report online creates additional administrative barriers for those who lack computers or internet access.

While the stated goal may be to provide new opportunities for enrollees to work, early data suggest that few enrollees may engage in new work-related activities. Early data from Arkansas show that the large majority of enrollees subject to new requirements are already meeting the requirements through work or compliance with SNAP or have an exemption, and few are newly reporting work or volunteer activities. The data do not explicitly identify individuals who have newly gained employment.67

Further into implementation, additional work support funding may be required, and Medicaid cannot pay for these services. If more enrollees become aware of the requirements and seek needed work supports, new resources may be required to provide training, caseworkers and other supports such as transportation, GED fees, and funds to purchase uniforms. Work support funding is key to overcoming barriers to work but cannot come from Medicaid dollars.

Coverage loss could result in gaps in care and increases in uncompensated care costs. Gaps in care, particularly for those with chronic physical or mental health conditions, could lead to more unnecessary hospitalizations or mental health crises. Individuals needing or undergoing treatment for substance use disorders could be particularly vulnerable to gaps in coverage that result in breaks in care.68 Providers could face additional uncompensated care costs that they may not be able to absorb. Coverage losses could reverse coverage gains experienced since the implementation of the ACA that accompanied more financial stability for providers.

Additional research and evaluation are necessary to answer key questions. Evaluation is required to understand whether the hypothesis that work requirements lead to “enhanced socioeconomic status, maintenance of health insurance coverage and improved health compared to the alternative outcome that needy individuals lose health coverage” is valid.69 Additional data could examine the following questions:

- How many enrollees are losing coverage, and of these, how many have other health insurance coverage or remain uninsured;

- How many enrollees are newly working and in what types of jobs;

- Whether enrollees understand the new requirements and use of the online portal, or whether they face barriers like lack of computers or internet to report work or exemptions successfully;

- How many enrollees might have been eligible for an exemption but did not obtain one; and

- How many individuals subject to disenrollment had good cause for not meeting the requirements.

More information is needed about the characteristics of disenrolled individuals, including barriers faced and more details about their current coverage status. More broadly, additional research can continue to examine what coverage losses and lock-outs mean for enrollees, providers and health plans. These formal waiver evaluations are important but often take a long time to complete. In the meantime, the early experience in Arkansas can provide valuable insights for other states considering similar policies.