People with Disabilities Are At Risk of Losing Medicaid Coverage Without the ACA Expansion

On November 10, 2020, the Supreme Court will hear oral argument in a case that could invalidate the entire Affordable Care Act (ACA), including the Medicaid expansion. Without the ACA, most people who gained coverage through the Medicaid expansion would likely become uninsured, and states would lose access to the enhanced federal matching funds to finance this coverage. Many people who qualify for the ACA Medicaid expansion have a disability, despite that they do not meet the strict medical standard to qualify for federal Supplemental Security Income (SSI) cash assistance benefits and therefore do not qualify for Medicaid on that basis. This data note presents the latest state-level data about nonelderly Medicaid adults who have disabilities but do not quality for SSI and considers the implications for their continued coverage if the ACA expansion is invalidated by the Court. Key findings include the following:

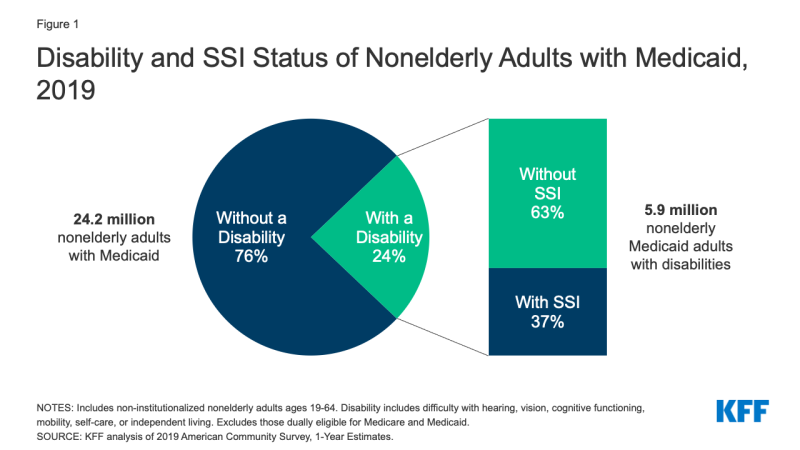

- More than six in 10 nonelderly Medicaid adults with disabilities do not receive SSI, meaning that they qualify for Medicaid on another basis. Nonelderly adults with disabilities who do not receive SSI can qualify for Medicaid based solely on their low income through the expansion group or as parents in non-expansion states. They also may qualify in a disability-related pathway offered at state option.

- The median share of nonelderly Medicaid adults with a disability but not SSI is higher in expansion states compared to non-expansion states (68% vs. 53%). The availability of the ACA expansion contributes to this difference because the expansion provides a pathway to Medicaid eligibility for people with disabilities, many of whom previously did not qualify. Prior to the ACA, childless adults did not qualify for Medicaid no matter how poor, and eligibility limits for parents were very low. If the Court also invalidates the ACA’s protections for people with pre-existing conditions and premium subsidies, people with disabilities who lose expansion coverage could have difficulty obtaining private market coverage.

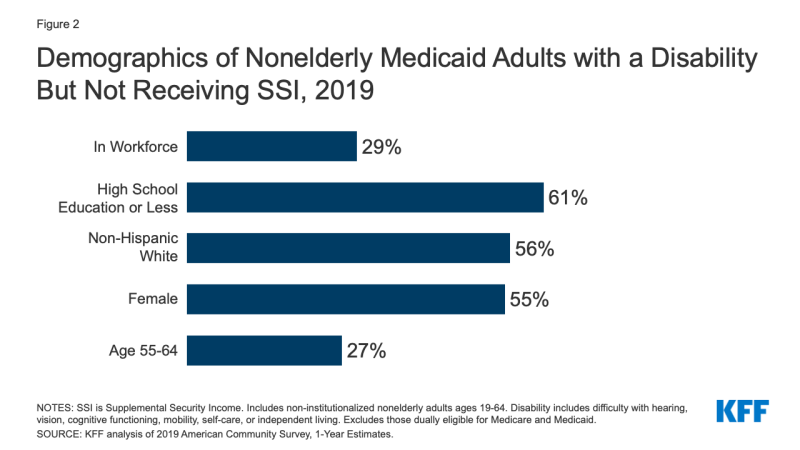

- Medicaid is a significant source of coverage for nonelderly adults with disabilities but not SSI, providing access to care for serious health conditions and supporting those who work. A majority of nonelderly Medicaid adults with disabilities but not SSI report serious difficulty with cognitive functioning and just under half report serious difficulty with mobility. Nearly three in 10 nonelderly Medicaid adults with disabilities but not SSI are in the workforce.

How is “disability” defined?

While SSI is sometimes used as a shorthand to identify people with disabilities, not all people with disabilities qualify for SSI. SSI is a monthly cash payment to help low-income people with disabilities pay for housing, food, and other basic needs. To qualify for SSI, individuals must have low incomes, limited assets, and an impaired ability to work at a substantial gainful level as a result of old age or significant disability. The SSI disability criteria are more stringent than other definitions of disability, such as those used in national surveys. The American Community Survey (ACS) classifies a person as having a disability if the person reports serious difficulty with hearing, vision, cognitive functioning (concentrating, remembering, or making decisions), mobility (walking or climbing stairs), self-care (dressing or bathing), or independent living (doing errands, such as visiting a doctor’s office or shopping, alone).1 The ACS definition of disability is intended to capture whether a person has a functional limitation that results in a participation limitation and also is used in other federal surveys, such as the Current Population Survey and the Survey of Income and Program Participation.

How do people with disabilities qualify for Medicaid?

While nearly a quarter of nonelderly adults with Medicaid report having a disability, relatively few of these enrollees qualify for Medicaid because they receive SSI benefits (Figure 1). While people who receive SSI generally automatically qualify for Medicaid, the SSI population encompasses only a subset of all people with disabilities. Over six in 10 nonelderly Medicaid adults with disabilities do not receive SSI (Figure 1). This group can be eligible for Medicaid as ACA expansion adults or Section 1931 parents (based solely on their low income). There is no way with federal survey data to separate people who qualify due to the Medicaid expansion from those who would have qualified under pre-ACA eligibility rules. They also may be eligible for Medicaid through an optional disability-related pathway (such as the state option to cover people with disabilities up to the federal poverty level or a home and community-based services waiver).2 Without the expansion pathway, Medicaid coverage for people with disabilities typically is limited to people who receive SSI because other disability-related pathways are provided at state option. And, in addition to using a more restrictive definition of disability compared to other measures, SSI income and asset limits are more restrictive than those required for Medicaid expansion adults and many optional disability-related Medicaid coverage pathways.3

Although it is not often thought of in these terms, the ACA expansion provides a significant Medicaid eligibility pathway for many people with disabilities. People covered in the Medicaid expansion group are sometimes erroneously described as “able-bodied adults.” While it is true that disability status is not one of the eligibility criteria to qualify for the expansion group, nonelderly adults with disabilities who do not receive SSI can qualify for Medicaid based solely on their income through the expansion group. Many people in the expansion group were previously ineligible for Medicaid. With the ACA expansion, Congress for the first time created a pathway in federal law for states to cover childless adults and low-income parents up to 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL, $17,609/year for an individual in 2020). Before the ACA, childless adults did not qualify for Medicaid, no matter how poor, and financial eligibility limits for “Section 1931” parents were tied to the former Aid to Families with Dependent Children cash assistance program and were very low, averaging 64% FPL nationally.

The median share of nonelderly Medicaid adults with a disability but not SSI is higher in expansion states compared to non-expansion states (68% vs. 53%) (Table 1). The availability of the ACA Medicaid expansion pathway contributes to this difference. Studies assessing the impact of the Medicaid expansion have identified coverage gains for people with disabilities as well as those with specific medical conditions or needs such as prescription drug users, people with substance use disorders including opioid use disorders, people with HIV, low-income adults who screened positive for depression, adults with diabetes, cancer patients/survivors, and adults with a history of cardiovascular disease or two or more cardiovascular risk factors. Nonelderly adults with disabilities who do not receive SSI also may qualify for Medicaid through an optional disability-related pathway. Greater shares of expansion states have adopted key optional disability-related pathways, compared to non-expansion states.4

Why is Medicaid coverage beyond the SSI pathway important for people with disabilities?

Even though their needs do not rise to the stringent SSI level, nonelderly Medicaid adults with disabilities but not SSI still report serious functional limitations that can affect their health, making coverage important. A majority (52%) of non-SSI Medicaid adults with disabilities report serious difficulty with cognitive functioning, and nearly half (46%) report serious difficulty with mobility.5 Two in five (40%) non-SSI Medicaid adults with disabilities report serious difficulty with independent living tasks, such as visiting a doctor’s office or shopping alone.6 Smaller shares report serious difficulty with vision (18%), self-care tasks such as dressing or bathing (17%), and hearing (13%), compared to the other limitations that make up the ACS disability definition.7 Nearly half (48%) of nonelderly Medicaid adults with a disability but not SSI have multiple functional limitations, reporting impairment in two or more of the six ACS areas.8

Just under three in 10 non-SSI Medicaid adults with disabilities are in the workforce, and having health insurance coverage can support their ability to work (Figure 2). National research has found increases in the share of individuals with disabilities reporting employment and decreases in the share reporting that they are not working due to a disability in Medicaid expansion states following expansion implementation, with no corresponding trends observed in non-expansion states, while other research has found a decline in SSI participation in expansion states. Disproportionate shares of non-SSI Medicaid adults with disabilities have a high school education or less (61%), are non-Hispanic white (56%), and are female (55%) (Figure 2). Just over one-quarter are ages 55 to 64, a population that is too young to qualify for Medicare based on older age but may not have access to other coverage (Figure 2). Studies have identified larger coverage gains for the near-elderly in expansion states compared to non-expansion states.

Looking Ahead

The ACA Medicaid expansion is a significant pathway to health insurance coverage for people with disabilities whose health needs do not rise to the stringent SSI level. These enrollees include people with serious, and often multiple, functional limitations that can affect health, including some who are in the workforce and others who are near elderly. If the Supreme Court invalidates the Medicaid expansion as part of the current case challenging the entire ACA, most expansion enrollees would likely become uninsured. These coverage losses would be in the 39 states (including DC) that have adopted the Medicaid expansion to date. The expansion group covers 15 million people as of June 2019, about 12 million of whom were newly eligible for Medicaid under the ACA (the remainder had been covered under Section 1115 waivers and subsequently moved to expansion group). Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and resulting economic issues, more people may have gained coverage through the Medicaid expansion, as overall program enrollment has been increasing since February 2020. Moreover, without the ACA, states that have not yet adopted the expansion would not have the option to do so in the future.

If the Court also invalidates the ACA’s protections for people with pre-existing conditions in the private market and premium subsidies, insurers could refuse to cover or charge higher rates to people based on their health status. This could make it difficult for people with disabilities who lose Medicaid expansion coverage to obtain private health insurance at all or coverage that is affordable. As part of the health care safety net, Medicaid never has excluded people with pre-existing conditions from coverage. In addition, without the Medicaid expansion, other gains in access, utilization, affordability, and addressing disparities resulting from expansion could be lost, and states and providers would lose federal funds that help them support health services and systems.

| Table 1: Nonelderly Medicaid Adults by Disability and SSI Status, 2019 | |||

| State | Total Nonelderly Medicaid Adults | Nonelderly Medicaid Adults with a Disability as a Share of Total Nonelderly Medicaid Adults | Nonelderly Medicaid Adults with a Disability But Not SSI as a Share of Nonelderly Medicaid Adults with a Disability |

| U.S. Total | 24,236,000 | 24% | 63% |

| Expansion States | 19,100,000 | Median 25% | Median 68% |

| Alaska | 61,000 | 23% | 77% |

| Arizona | 633,000 | 23% | 71% |

| Arkansas | 276,000 | 32% | 72% |

| California | 4,455,000 | 16% | 68% |

| Colorado | 403,000 | 22% | 74% |

| Connecticut | 345,000 | 19% | 73% |

| Delaware | 78,000 | 23% | 72% |

| District of Columbia | 86,000 | 29% | 63% |

| Hawaii | 100,000 | 17% | 72% |

| Illinois | 940,000 | 22% | 66% |

| Indiana | 445,000 | 30% | 67% |

| Iowa | 241,000 | 25% | 72% |

| Kentucky | 479,000 | 32% | 66% |

| Louisiana | 544,000 | 25% | 69% |

| Maine | 97,000 | 36% | 66% |

| Maryland | 459,000 | 22% | 69% |

| Massachusetts | 707,000 | 20% | 63% |

| Michigan | 930,000 | 27% | 65% |

| Minnesota | 412,000 | 23% | 71% |

| Montana | 86,000 | 15% | 61% |

| Nevada | 224,000 | 23% | 71% |

| New Hampshire | 69,000 | 32% | 73% |

| New Jersey | 577,000 | 20% | 64% |

| New Mexico | 296,000 | 22% | 70% |

| New York | 2,309,000 | 18% | 64% |

| North Dakota | 34,000 | 32% | 81% |

| Ohio | 1,010,000 | 27% | 65% |

| Oregon | 402,000 | 26% | 72% |

| Pennsylvania | 1,030,000 | 30% | 64% |

| Rhode Island | 98,000 | 25% | 52% |

| Vermont | 65,000 | 25% | 62% |

| Virginia | 397,000 | 27% | 66% |

| Washington | 604,000 | 25% | 66% |

| West Virginia | 208,000 | 32% | 61% |

| Non-Expansion States | 5,136,000 | Median 33% | Median 53% |

| Alabama | 245,000 | 36% | 47% |

| Florida | 1,000,000 | 28% | 53% |

| Georgia | 435,000 | 34% | 48% |

| Idaho* | 65,000 | 36% | 53% |

| Kansas | 103,000 | 39% | 54% |

| Mississippi | 171,000 | 37% | 50% |

| Missouri* | 244,000 | 39% | 62% |

| Nebraska* | 58,000 | 29% | 46% |

| North Carolina | 509,000 | 29% | 52% |

| Oklahoma* | 144,000 | 34% | 54% |

| South Carolina | 282,000 | 29% | 56% |

| South Dakota | 26,000 | 25% | 42% |

| Tennessee | 447,000 | 33% | 58% |

| Texas | 949,000 | 33% | 50% |

| Utah* | 91,000 | 32% | 55% |

| Wisconsin | 348,000 | 29% | 62% |

| Wyoming | 20,000 | 35% | 49% |

| NOTES: Includes non-institutionalized adults ages 19-64. Excludes those dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. Totals may not sum due to rounding. *MO and OK have adopted but not yet implemented the expansion. NE implemented 10/1/20, and ID and UT implemented 1/1/20, so these states are considered non-expansion states for this analysis. SOURCES: KFF analysis of the 2019 American Community Survey, 1-Year Estimates; KFF, Status of State Medicaid Expansion Decisions (Oct. 16, 2020). |

|||